Bellatoripes

Bellatoripes (Latin for "warlike foot") is an ichnogenus of footprint produced by a large theropod dinosaur so far known only from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta and British Columbia in Canada. The tracks are large and three-toed, and based on their size are believed to have been made by tyrannosaurids, such as Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus. Fossils of Bellatoripes are notable for preserving trackways of multiple individual tyrannosaurids all travelling in the same direction at similar speeds, suggesting the prints may have been made by a group, or pack, of tyrannosaurids moving together. Such inferences of behaviour cannot be made with fossil bones alone, so the record of Bellatoripes tracks together is important for understanding how large predatory theropods such as tyrannosaurids may have lived.

| Bellatoripes Temporal range: Upper Cretaceous | |

|---|---|

| |

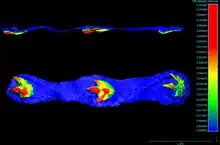

| Bellatoripes fredlundi track and trackway in situ | |

| Trace fossil classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Tyrannosauridae |

| Ichnofamily: | †Tyrannosauripodidae McCrea et al., 2014 |

| Ichnogenus: | †Bellatoripes McCrea et al., 2014 |

| Type ichnospecies | |

| †Bellatoripes fredlundi McCrea et al., 2014 | |

Discovery and classification

Bellatoripes was named in 2014 from a tracksite discovered in the Wapiti Formation, British Columbia containing the trackways of three separate track-makers, but isolated individual prints were already known prior to this discovery, including one from the Wapiti Formation and another from Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta. The trackway was first discovered by a local guide-outfitter Aaron Fredlund from two footprints in October 2011, and the rest of the track site was fully excavated by August 2012. Three distinct trackways were identified, Trackway A consisting of three footprints (the holotype specimen), Trackway B of just one, and Trackway C with two prints. The track types were assigned to a new ichnogenus and ichnospecies, Bellatoripes fredlundi, named after Fredlund for his discovery.[1]

The closest comparable ichnogenus to Bellatoripes in shape is Tyrannosauripus, a single track from the younger late Maastrichtian of New Mexico attributed to Tyrannosaurus. Bellatoripes is distinguished from Tyrannosauripus by its smaller size, lack of separate soft-tissue pad impressions along its digits, and hallux impressions that face forward (compared to the inward-facing hallux impression of Tyrannosauripus). Nonetheless, the close similarity in soft-tissue traits between the two ichnogenera prompted McCrea and colleagues to coin the ichnofamily Tyrannosauripodidae, to which they also referred similar, unnamed prints from the Nemegt Formation in Mongolia. The ichnofamily was named for the presumed track-makers of these prints, theropods from the family Tyrannosauridae.[1]

Bellatoripes and other tyrannosauripodids share a number of unique features that distinguish them from other known large theropod footprints, including a large heel pad and thick digits that lack distinct toe pads and taper in width towards the claws. Bellatoripes and other tyrannosauripodid tracks cannot be definitively assigned to Tyrannosauridae based on shared morphological traits alone, but the absence of other large theropods from the same geographical areas and stratigraphic ages precludes any other identities for the trackmakers. It is possible then that the soft-tissue features of Bellatoripes and tyrannosauripodid tracks are synapomorphies of Tyrannosauridae as a whole.[1]

Description

Bellatoripes tracks are large, tridactyl, and bipedal pes prints, with the middle (third) toe being the longest (mesaxonic) and all toes bearing sharp, pointed claw impressions, typical of theropod footprints. The prints indicate the feet were robust and encased in thick soft tissues, including broad heel pads and thick digits that gradually taper out in thickness along their length. Bellatoripes footprints are over 50 centimetres (20 in) in length, and trackways record pace lengths of nearly 175 centimetres (5.74 ft) and strides of almost 350 centimetres (11.5 ft), leading to an estimated hip height for the track-maker at 2.3 metres (7.5 ft). A clawed hallux is preserved on some of the prints, but its identification has been disputed and these impressions have alternatively suggested to be from the base of the second toe.[1][2]

Skin impressions of Bellatoripes preserve small, tuberculate scales, typical of theropod feet.[1]

Palaeobiology

The presence of three, parallel Bellatoripes trackways inferred to have been created in a short span of time is suggested to indicate that tyrannosaurids were social, gregarious animals that travelled in groups. Similar suggestions could only be made from skeletal evidence from body fossils alone, such as assemblages of multiple individuals preserved together at one locality.[3] The sedimentary conditions to preserve the tracks implies that they were made within a short span of time, and other tracks at the same site (including those of a hadrosaur and a smaller theropod) are more randomly oriented, implying that the animals were not constrained along the same path by a geographical barrier. Bellatoripes tracks are the first evidence from traces of living tyrannosaurids to support the suggestion that they lived in groups.[1]

The trackways of Bellatoripes allowed for the speed the track-maker was travelling at to be calculated, using the estimated hip height and stride lengths. This speed was calculated to be around 6.4 kilometres per hour (4.0 mph) to 8.5 kilometres per hour (5.3 mph), and is inferred to represent the preferred walking gait of tyrannosaurid theropods. Similarly, the age of the track-makers could be inferred from the dimensions of the footprints compared to the estimated hip height based upon contemporary tyrannosaurids that likely produced Bellatoripes tracks (Albertosaurus, Gorgosaurus, and Daspletosaurus). The track-makers were estimated to be between 25–29 years old, within the known upper age range of tyrannosaurid lifespans and indicating that the animals were mature adults.[1]

The fine preservation of the distal digits and small, parallel striations (interpreted as drag marks) within Bellatoripes tracks suggests that the track-makers partially withdrew their feet backwards before stepping forward, leaving the overlying sediment undisturbed. This contrasts with what is typically seen in other theropod footprints, where the tips of the digits drag as they are pulled forward, but is similar to the observed movements of ostrich feet during locomotion.[1][4]

Palaeopathology

In the Wapiti Trackway A, the second digit of the left foot appears consistently truncated in both footprints #1 and #3, suggesting that the foot of the track-maker was injured in some way. The truncation suggests either the amputation of the claw and associated toe bone (phalanx) or a deformation or dislocation that kept the outer toe from contacting the ground, although the rough and uneven margin of the 'nub' at the tip of the impression suggests that the former is more likely from the loss of tissue and bone. Despite this, the dimensions of the trackway indicate that the injury did not negatively impact the animal's locomotion, with only a slight outward rotation of the right foot to compensate. The animal was otherwise moving at a similar speed and gait to the those that produced the other trackways.[1]

Alternatively, Weems (2019) proposed that the truncation of digit II in trackway A was not an injury, but due to the trackmaker shifting its weight leftwards in response to its right foot sinking more deeply into the substrate, leaving an imperfect and poorly depressed digit II impression.[2]

References

- McCrea, R. T.; Buckley, L. G.; Farlow, J. O.; Lockley, M. G.; Currie, P. J.; Matthews, N. A.; Pemberton, S. G. (2014). "A 'Terror of Tyrannosaurs': The First Trackways of Tyrannosaurids and Evidence of Gregariousness and Pathology in Tyrannosauridae". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e103613. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j3613M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103613. PMC 4108409. PMID 25054328.

- Robert E. Weems (2019). "Evidence for bipedal prosauropods as the likely Eubrontes track-makers". Ichnos: An International Journal for Plant and Animal Traces. 26 (3): 187–215. doi:10.1080/10420940.2018.1532902. S2CID 133770251.

- Currie, P.J; Eberth, D.A. (2010). "On gregarious behavior in Albertosaurus". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 47 (9): 1277–1289. Bibcode:2010CaJES..47.1277C. doi:10.1139/e10-072.

- Avanzini, M.; Pinuela, L.; Garcia-Ramos, J. C. (2012). "Late Jurassic footprints reveal walking kinematics of theropod dinosaurs". Lethaia. 45 (2): 238–252. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00276.x.