Bayonne Statute

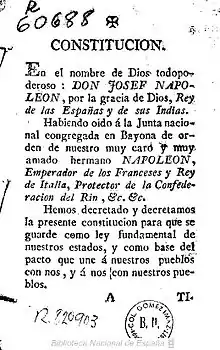

The Bayonne Statute (Spanish: Estatuto de Bayona),[1] also called the Bayonne Constitution (Constitución de Bayona)[2] or the Bayonne Charter (Carta de Bayona),[1] [lower-alpha 1] was a constitution or a royal charter (carta otorgada)[4] approved in Bayonne, France, 6 July 1808, by Joseph Bonaparte as the intended basis for his rule as king of Spain.

The constitution was Bonapartist in overall conception, with some specific concessions made in an attempt to accommodate Spanish culture. Few of its provisions were ever put into effect: his reign as Joseph I of Spain was largely consumed by continuous conventional and guerrilla war as part of the Peninsular War.[5]

Background

In 1808, after a period of shaky alliance between the Spanish Antiguo Régimen and the Napoleonic French First Empire, the Mutiny of Aranjuez (17 March 1808) removed the king's minister Manuel de Godoy, Prince of the Peace, and led to the abdication of king Charles IV of Spain (19 March 1808).[5][6] His son Ferdinand VII briefly held the reins of power, but Napoleon determined to settle the monarchy of Spain on a member of his own family: his older brother Joseph, conferred the title Prince of Spain to be hereditary on his children and grandchildren in the male and female line.[5]

On 5 May 1808,[7] Charles IV renounced his rights to the Spanish Crown in favor of Napoleon. Later the same day, Ferdinand VII, unaware of Charles's abdication, abdicated in favor of his father, effectively passing the Crown to Napoleon.[5] Along with other Spanish members of the House of Bourbon, including Infante Antonio Pascual of Spain, they went into a comfortable, if forced, exile in France,[8] at the Château de Valençay.

In an attempt to conform at least mildly to the tradition of legal continuity, Napoleon ordered his general Joachim Murat, Grand Duke of Berg, to convene in Bayonne a Cortes of thirty deputies chosen from among the notables of Spain to help draft and to approve the constitutional basis for the new regime. However, in the context of the Dos de Mayo Uprising in Madrid and various other uprisings elsewhere in Spain, only about a third of the invited Spanish notables attended.[5] On 4 June 1808,[9] Napoleon designated his brother Joseph as king of Spain;[5] he was proclaimed king at Madrid on 25 July.[10] The rump Cortes began meeting in Bayonne on 15 June[9] to begin drafting a "constitution",[5] for which Napoleon provided them with an extensive initial draft;[11] it was promulgated July 8.[9]

Content

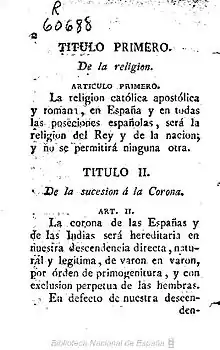

The Bayonne Statute placed many nominal limits on royal power, but few effective ones.[5] There was to be a tricameral legislature; nine ministers (as against five or six in recent Bourbon governments); an independent judiciary; and various individual liberties were recognized, though not freedom of religion. Although generally Bonapartist in conception, the statute shows clear influence by the few Spanish notables who were involved in drafting it that it retained Catholicism as a state religion, and banned all other religions. In the Spanish tradition, it was promulgated "In the name of God Almighty" ("En el nombre de Dios Todopoderoso").[5]

In the event, most provisions of the Statute were never put into practice: throughout the entire Bonapartist period in Spain, the constitution was effectively suspended by French military authorities.[5] Most decisions were made by Napoleon and his generals, not by King Joseph.[10] Nonetheless, French-controlled Spain saw some serious attempts at liberal reform, though many of them ignored the Bayonne Statute[10] and, of course, this legislation was not recognized after the Bourbons were restored. The new regime abolished feudalism, the Inquisition, and the Council of Castile; suppressed numerous convents and monasteries as well as all military orders; declared that no new mayorazgos could be created; divided the country into French-style departments; abolished internal customs borders and many state monopolies; abolished the Mesta (a powerful association of sheep holders) and the tax known as the Voto de Santiago; privatized numerous state-owned factories; and began to introduce the Napoleonic Code into Spain's system of law.[12]

Footnotes

Notes

- Ignacio Fernández Sarasola, Ignacio Pérez Sarasola, La primera Constitución española: El Estatuto de Bayona Archived 2013-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- Ignacio Fernández Sarasola, La Constitución de Bayona (1808), ISBN 978-84-96717-74-9. Listing retrieved 2010-03-12.

- Constitution of 1808

- de Mendoza, Alfonso Bullon; de Valugera, Gomez (1991). Alonso, Javier Parades (ed.). Revolución y contrarrevolución en España y América (1808–1840). p. 78. ISBN 84-87863-03-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - de Mendoza, Alfonso Bullon; de Valugera, Gomez (1991). Alonso, Javier Parades (ed.). Revolución y contrarrevolución en España y América (1808–1840). pp. 71–73. ISBN 84-87863-03-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Esdaile (2000), p. 14 for dates.

- Esdaile (2000), p. 15 for date.

- Martin Hume, Modern Spain, T. Fisher Unwin Ltd (original copyright 1899, Third Edition, 1923), p. 118–122. Multiple versions available online, copy at archive.org retrieved 2010-03-12.

- Cronología. Desde Trafalgar hasta la proclamación de la II República. 1805–1931, Sociedad Benéfica de Historiadores Aficionados y Creadores. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- de Mendoza, Alfonso Bullon; de Valugera, Gomez (1991). Alonso, Javier Parades (ed.). Revolución y contrarrevolución en España y América (1808–1840). pp. 74–75. ISBN 84-87863-03-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Although Napoleon's initial version is lost, Bullon and Gomez (op. cit.) write, "...es cierto que a la asamblea... se le ofreció por Napoleón un proyecto ya muy maduro, y que sus atribuciones eran tan solo consultativas": "it is certain that Napoleon presented the assembly an already mature draft, and that their role was almost entirely consultative".

- Esdaile, Charles J. (2000). Spain in the Liberal Age. Blackwell. pp. 26–27. ISBN 0-631-14988-0.

Further reading

- Amaya León, Wilman. "El Estatuto de Bayona. La primera carta liberal de América Latina." Verba Iuris 33 (2015).

- Andrews, Catherine. "Moderation vs. Conservation: State Councils and Senates in Mexico’s First Constitutional Proposals." Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 33.1 (2017): 153–166.

- Aranguren, Juan Cruz Alli. "El marco histórico e institucional de la Constitución de Bayona." Revista internacional de los estudios vascos= Eusko ikaskuntzen nazioarteko aldizkaria= Revue internationale des ètudes basques= International journal on Basque studies, RIEV 4 (2009): 197–222.

- Burdiel, Isabel. "Myths of failure, myths of success: new perspectives on nineteenth-century Spanish liberalism." The Journal of Modern History 70.4 (1998): 892–912.

- Busaall, Jean Baptiste. "Constitution et culture constitutionnelle. La Constitution de Bayonne dans la monarchie espagnole." Revista internacional de los estudios vascos 4 (2009): 73–96.

- Busaall, Jean-Baptiste. "Révolution et transfert de Droit: La portée de la Constitution de Bayonne." Historia constitucional: Revista Electrónica de Historia Constitucional 9 (2008): 1–1.

- Busaall, Jean-Baptiste. "À propos de l'influence des constitutions françaises depuis 1789 sur les premières constitutions écrites de la monarchie espagnole: L'exemple de l'ordonnancement territorial dans la Constitution de Bayonne (1808)." Iura vasconiae: revista de derecho histórico y autonómico de Vasconia 8 (2011): 9–40.

- Busaall, Jean-Baptiste. "LA CONSTITUTION DE BAYONNE DE 1808 ET LʼHISTOIRE CONSTITUTIONNELLE HISPANIQUE." Teoría y Derecho 10 (2011): 67–79.

- Busaall, Jean-Baptiste. "Les origins du pouvoir constituant en Espagne, la Constitution de Bayonne (1808)." Cadice e Oltre: Costituzione, Nazione e (2015).

- Conard, Pierre. La constitution de Bayonne (1808): essai d'édition critique. Cornély, 1910.

- Escudero López, José Antonio. "La Administración Central en la Constitución de Bayona." Revista internacional de los estudios vascos= Eusko ikaskuntzen nazioarteko aldizkaria= Revue internationale des ètudes basques= International journal on Basque studies, RIEV 4 (2009): 277–291.

- Lafourcade, Maïté. "Des premières constitutions françaises à la Constitution de Bayonne." Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos, Cuadernos (2009).

- Martin, Arnaud. "Les drois individuels dans la Constitution de Bayonne." Revista internacional de los estudios vascos= Eusko ikaskuntzen nazioarteko aldizkaria= Revue internationale des ètudes basques= International journal on Basque studies, RIEV 4 (2009): 293–313.

- Martínez Pérez, Fernando. "La Constitución de Bayona y la experiencia constitucional josefina." Historia y política: Ideas, procesos y movimientos sociales 19 (2008): 151–171.

- Martiré, Eduardo. "La importancia institucional de la Constitución de Bayona en el constitucionalismo hispanoamericano." Historia constitucional: Revista Electrónica de Historia Constitucional 9 (2008): 6–127.

- Masferrer, Aniceto. "Plurality of Laws, Legal Traditions and Codification in Spain." J. Civ. L. Stud. 4 (2011): 419. – calls it statute

- Morange, Claude. "A propos de «l’inexistence» de la Constitution de Bayonne." Historia Constitucional 10 (2009): 1–40.

- Pérez, Antonio-Filiu Franco. "La" cuestión americana" y la Constitución de Bayona (1808)." Historia constitucional: Revista Electrónica de Historia Constitucional 9 (2008): 5–109.

- Robertson, William Spence. "The juntas of 1808 and the Spanish colonies." The English Historical Review 31.124 (1916): 573–585.

- Ternavasio, Marcela. "The impact of Hispanic Constitutionalism in the Río de la Plata." The Rise of Constitutional Government (2015): 133–149.

- Villegas Martín, Juan. "El proceso de independencia en el Cono Sur americano: del virreinato del Río de la Plata a la República Argentina." Revista Temas 6 (2012): 9–32

External links

- (in Spanish) Text of the statute on Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library

- (in Spanish) Text of the statute on WikiSource

- (in Spanish) Constitution of 1808