Battle of Ticinus

The battle of Ticinus was fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and a Roman army under Publius Cornelius Scipio in late November 218 BC as part of the Second Punic War. It took place in the flat country on the right bank of the river Ticinus, to the west of modern Pavia in northern Italy. Hannibal led 6,000 Libyan and Iberian cavalry, while Scipio led 3,600 Roman, Italian and Gallic cavalry and a large but unknown number of light infantry javelinmen.

| Battle of Ticinus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

.jpg.webp) Eighteenth-century depiction of the battle, showing the younger Scipio rescuing his wounded father | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Carthage | Rome | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hannibal | Publius Scipio (WIA) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,000 cavalry |

3,600 cavalry Up to 4,500 velites Up to 2,000 mounted Gallic infantry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | Heavy | ||||||

War had been declared early in 218 BC over perceived infringements of Roman prerogatives in Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal) by Hannibal. Hannibal had gathered a large army, marched out of Iberia, through Gaul (modern France) and over the Alps into Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy), where many of the local tribes were opposed to Rome. The Romans were taken by surprise, but one of the consuls for the year, Scipio, led an army along the north bank of the Po with the intention of giving battle to Hannibal. The two commanding generals each led out strong forces to reconnoitre their opponents. Scipio mixed many javelinmen with his main cavalry force, anticipating a large-scale skirmish. Hannibal put his close-order cavalry in the centre of his line, with his light Numidian cavalry on the wings.

On sighting the Roman infantry the Carthaginian centre immediately charged and the javelinmen fled back through the ranks of their cavalry. A large cavalry melee ensued: many cavalry dismounted to fight on foot and some of the Roman javelinmen reinforced the fighting line. This continued indecisively until the Numidians swept round both ends of the line of battle. They then attacked the still disorganised javelinmen; the small Roman cavalry reserve, to which Scipio had attached himself; and the rear of the already engaged Roman cavalry. All three of these Roman forces were thrown into confusion and panic.

The Romans broke and fled, with heavy casualties. Scipio was wounded and only saved from death or capture by his 16-year-old son. That night Scipio broke camp and retreated over the Ticinus; the Carthaginians captured 600 of his rearguard the next day. After further manoeuvres Scipio established himself in a fortified camp to await reinforcements while Hannibal recruited among the local Gauls. When the Roman reinforcements arrived in December under Tiberius Longus, Hannibal heavily defeated him at the battle of the Trebia. The following spring, strongly reinforced by Gallic tribesmen, the Carthaginians moved south into Roman Italy. Hannibal campaigned in southern Italy for the next 12 years.

Background

Iberia

The First Punic War was fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. They struggled for supremacy primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters, and also in North Africa.[1] The war lasted for 23 years, from 264 to 241 BC, until the Carthaginians were defeated.[2][3] The Treaty of Lutatius was signed by which Carthage evacuated Sicily and paid an indemnity of 3,200 talents[note 1] over ten years.[5] Four years later, when Carthage was weakened by the mutiny of part of its army and the rebellion of many of its African possessions, Rome seized Sardinia and Corsica on a cynical pretence and imposed a further 1,200 talent indemnity.[note 2][6][7] The annexation of Sardinia and Corsica by Rome and the additional financial imposition fuelled resentment in Carthage.[8][9] The contemporary Greek historian Polybius considered this act of bad faith by the Romans to be the single greatest cause of war with Carthage breaking out again nineteen years later.[10]

Shortly after Rome's breach of the treaty the leading Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca led many of his veterans on an expedition to expand Carthaginian holdings in south-east Iberia (today Iberia consists of Spain and Portugal); this was to become a quasi-monarchial, autonomous Barcid fiefdom.[11] Carthage gained silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower, military facilities such as shipyards, and territorial depth which encouraged it to stand up to future Roman demands.[12] Hamilcar ruled as a viceroy and was succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, in 229 BC and then his son, Hannibal, eight years later.[13][14] In 226 BC the Ebro Treaty was agreed with Rome, specifying the river Ebro as the northern boundary of the Carthaginian sphere of influence.[15] A little later Rome made a separate treaty with the city of Saguntum, which was situated well south of the Ebro.[16] In 218 BC a Carthaginian army under Hannibal besieged, captured and sacked Saguntum[17][18] and early the following year Rome declared war on Carthage.[19]

Cisalpine Gaul

Since the end of the First Punic War Rome had also been expanding, especially in the area of north Italy either side of the river Po known as Cisalpine Gaul. Roman attempts to establish towns and farms in the region from 232 BC led to repeated wars with the local Gallic tribes, who were finally defeated in 222 BC. In 218 BC the Romans pushed even further north, establishing two new towns, or "colonies", on the Po and appropriating large areas of the best land. Most of the Gauls simmered with resentment at this intrusion.[20] The major Gallic tribes in Cisalpine Gaul attacked the Roman colonies there, causing the Romans to flee to their previously established colony of Mutina (modern Modena), where they were besieged. A Roman relief army broke through the siege, but was then ambushed and itself besieged in Tannetum.[21]

It was the long-standing Roman procedure to elect two men each year, known as consuls, to each lead an army.[22] In 218 BC the Romans raised an army to campaign in Iberia under the consul Publius Scipio, who was accompanied by his brother Gnaeus. The Roman Senate detached one Roman and one allied legion from the force intended for Iberia to reinforce the Roman position in northern Italy. The Scipios had to raise fresh troops to replace these and thus could not set out for Iberia until September.[23] At the same time another Roman army in Sicily under the consul Sempronius Longus was preparing for an invasion of Carthaginian Africa.[24]

Carthage invades Italy

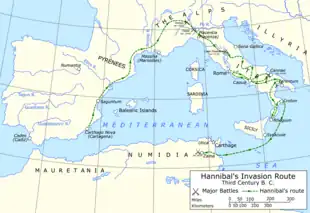

Meanwhile, Hannibal assembled a Carthaginian army in New Carthage (modern Cartagena) over the winter, marching north in May 218 BC. He entered Gaul to the east of the Pyrenees, then took an inland route to avoid the Roman allies along the coast.[25][26] Hannibal left his brother Hasdrubal Barca in charge of Carthaginian interests in Iberia. The Roman fleet carrying the Scipio brothers' army landed at Rome's ally Massalia (modern Marseille) at the mouth of the Rhone in September, at about the same time as Hannibal was fighting his way across the river against a force of local Gauls at the battle of Rhone Crossing.[26][27][28] A Roman cavalry patrol scattered a force of Carthaginian cavalry, but Hannibal's main army evaded the Romans and Gnaeus Scipio continued to Iberia with the Roman force;[29][30] Publius returned to northern Italy to coordinate the immediate Roman response there.[30] The Carthaginians crossed the Alps with 38,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry in October 218 BC, surmounting the difficulties of climate, terrain[25] and the guerrilla tactics of the native tribes.[31]

Hannibal arrived with 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and 37 elephants[32][33] in what is now Piedmont, northern Italy. The Romans had already withdrawn to their winter quarters and were astonished by Hannibal's appearance. His surprise entry into the Italian peninsula led to the cancellation of Rome's planned invasion of Africa by an army under Longus.[34] The Carthaginians needed to obtain supplies of food, as they had exhausted their reserves. They also wished to obtain allies among the north-Italian Gallic tribes from which they could recruit, as Hannibal believed that he required a larger army if he were to effectively take on the Romans. The local tribe, the Taurini, were unwelcoming, so Hannibal promptly besieged their capital, (near the site of modern Turin) stormed it, massacred the population and seized the supplies there.[35][36] The modern historian Richard Miles believes that with these brutal actions Hannibal was sending out a clear message to the other Gallic tribes as to the likely consequences of non-cooperation.[37]

Hearing that Publius Scipio was operating in the region, he assumed the Roman army in Massala which he had believed en route to Iberia had returned to Italy and reinforced the army already based in the north.[note 3] Believing he would therefore be facing a much larger Roman force than he had anticipated, Hannibal felt an even more pressing need to recruit strongly among the Cisalpine Gauls. He determined that a display of confidence was called for and advanced boldly down the valley of the Po. However, Scipio led his army equally boldly against the Carthaginians, causing the Gauls to remain neutral.[38][39] Both commanders attempted to inspire the ardour of their men for the coming battle by making fiery speeches to their assembled armies. Hannibal is reported to have stressed to his troops that they had to win, whatever the cost, as there was no place they could retreat to.[40]

After camping at Piacenza, a Roman colony founded earlier that year,[note 4] the Romans created a pontoon bridge across the lower river Ticinus (the modern Ticino) and continued west. When his scouts reported the nearby presence of Carthaginians, Scipio ordered his army to encamp. The Carthaginians did the same.[41] Next day each commander led out a strong force to personally reconnoitre the size and make up of the opposing army, about which they would have been almost completely ignorant.[42][43]

Opposing forces

Anticipating an engagement as he closed with the Romans, Hannibal had recalled all of his scouts and raiding parties[44] and took with him an exclusively cavalry force which included almost all of his 6,000-strong mounted contingent. Carthage usually recruited foreigners to make up its army. Many were from North Africa, and are usually referred to as Libyans; the region provided two main types of cavalry: close-order shock cavalry (also known as "heavy cavalry") carrying spears; and light cavalry skirmishers from Numidia who threw javelins from a distance and avoided close combat.[45][46] Iberia also provided experienced cavalry: unarmoured close-order troops[47] referred to by the ancient historian Livy as "steady", meaning that they were accustomed to sustained hand-to-hand combat rather than hit and run tactics. Hannibal's cavalry contingent would have consisted almost entirely of these three types, but the numbers of each are not known.[48]

Most male Roman citizens were liable for military service and would serve as infantry, with a better-off minority providing a cavalry component. Traditionally, when at war the Romans would raise two or more legions, each of 4,200 infantry[note 5] and 300 cavalry. Approximately 1,200 of the infantry in each legion, poorer or younger men unable to afford the armour and equipment of a standard legionary, served as javelin-armed skirmishers, known as velites. They carried several javelins, which would be thrown from a distance, a short sword, and a 40-centimetre (1 ft 4 in) shield.[51] An army was usually formed by combining one or several Roman legions with the same number of similarly sized and equipped legions provided by their Latin allies; allied legions usually had a larger attached complement of cavalry than Roman ones.[22][52] Scipio's army consisted of four legions, with approximately 16,000 infantry and 1,600 cavalry.[53] A further 2,000 Gallic cavalry and many Gallic infantry were also serving with the Romans.[54] Scipio led out all of his 3,600 cavalry and, anticipating that they would be outnumbered, supplemented them with a large but unknown number of the 4,500 or so available velites.[42]

Battle

Neither the precise date nor the precise location of the battle are known: it took place in late November 218 BC on the flat country on the west bank of the Ticinus, not far from modern Pavia.[40][55][56] The ancient historians Livy and Polybius both give accounts of the battle, which agree on the main events, but differ in some of the details.[57] Formal battles were usually preceded by the two armies camping two to twelve kilometres (1–7 mi) apart for days or weeks; sometimes forming up in battle order each day. In such circumstances either commander could prevent a battle from occurring, and unless both commanders were willing to at least some degree to give battle the stand off would end with one army simply marching off without engaging.[58][59] Many battles were decided when one side was partially or wholly enveloped and their infantry were attacked in the flank or rear. It was unusual, prior to Ticinus, for one side's more mobile cavalry to be similarly enveloped.[46][60] During periods when armies were encamped in close proximity it was common for their light forces to skirmish with each other, attempting to gather information on each other's forces and achieve minor, morale-raising victories. These were typically fluid affairs and viewed as preliminaries to any subsequent battle.[42][61]

.jpg.webp)

Hannibal placed his cavalry in a line with the close-order formations in the centre. The more manoeuvrable Numidian cavalry were positioned on the flanks and possibly held back slightly.[57][62] Scipio, who had gained a low opinion of the Carthaginian cavalry from the clash near the Rhone, expected an extended exchange of javelins and hoped that his velites, being smaller targets and better able to shelter behind their shields than the Carthaginian horses, would come off best. He arranged the 2,000 Gallic cavalry to the front of his formation – many or all of them would have carried a javelinman riding behind each of the cavalrymen, as was their tradition. Scipio positioned the velites in close support of the Gauls.[42][61][62][63] On sighting the enemy, the velites sallied forward from behind their cavalry to advance within javelin-hurling range. On seeing this, the whole of the Carthaginian close-order cavalry promptly charged them. The Roman light infantry, realising they would be cut down if the Carthaginians came into contact with them, turned and fled, making no attempt to throw their missiles.[64] The Roman cavalry, who were all close order attempted to counter charge the Carthaginians.[note 6] They were obstructed by the large number of their infantry attempting to pass through their ranks to the rear, and in the case of the Gallic cavalry, possibly by still having a javelinman riding into battle behind each of the cavalrymen.[62] The modern historian Philip Sabin comments that the Roman cavalry and infantry got into a "dreadful tangle".[63]

The cavalry did not move into contact at speed, but at a fast walk or slow trot; any faster would have "ended in a growing pile of injured men and horses", according to the modern historian Sam Koon.[66] Once in contact with the enemy, many of the cavalrymen dismounted to fight; this was a frequent occurrence in Punic War cavalry combat.[42][63][67] There is debate among modern scholars as to the reasons for this common tactic.[note 7] Certainly the second men on some, and possibly all, of the 2,000 Gallic cavalry's horses dismounted and joined the fight.[62] Some of the Roman javelinmen also reinforced their cavalry comrades, but the extent to which this occurred is unclear.[70] The ensuing melee is recorded as continuing for some time, with no clear advantage being gained by either side.[71][72]

Then the Carthaginian light cavalry swept round both ends of the line of battle, attacking the still disorganised velites and the small Roman cavalry reserve, where Scipio had positioned himself. These Carthaginians also threatened, and threw javelins at, the rear of the already engaged Roman troops, throwing them into confusion and panic.[42][64] The velites, still aware of their vulnerability to cavalry, immediately fled. The Roman reserve cavalry attempted to protect the rear of the fighting line, but were surrounded and Scipio was badly wounded. The main force of Roman cavalry, attacked from both sides, was routed and suffered heavy losses.[62][73] In the confusion Scipio's 16-year-old son, also named Publicus Cornelius Scipio, cut his way through to his wounded father at the head of a small group; he escorted him away from the fight, saving him from being either captured or killed.[note 8][64] The losses suffered by each side are not known, but the Roman casualties are believed to have been severe.[24]

The surviving Roman forces regathered at their camp, still held by their heavy infantry. Aware the Carthaginians could now use their superiority in cavalry to isolate his camp, Scipio withdrew during the night back over the Ticinus. He left a force behind to dismantle the pontoon bridge so the Carthaginians would be unable to follow. Hannibal pursued the next day and captured 600 men from this rearguard, but not before the bridge had been rendered impassable.[71]

Aftermath

The Romans withdrew as far as Piacenza. Two days after Ticinus the Carthaginians crossed the river Po, and then marched to Piacenza. They formed up outside the Roman camp and offered battle, which Scipio refused. The Carthaginians set up their own camp some 8 kilometres (5 mi) away.[74] That night 2,200 Gallic troops serving with the Roman army attacked the Romans closest to them in their tents, and deserted to the Carthaginians; taking the Romans' heads with them as a sign of good faith.[3][54] Hannibal rewarded them and sent them back to their homes to enrol more recruits. Hannibal also made his first formal treaty with a Gallic tribe, and supplies and recruits started to come in.[74] The Romans abandoned their camp and withdrew under cover of night. The next morning the Carthaginian cavalry bungled their pursuit and the Romans were able to set up camp on an area of high ground by the river Trebbia at what is now Rivergaro. Even so, they had to abandon much of their baggage and heavier gear, and many stragglers were killed or captured.[75] Scipio waited for reinforcements while Hannibal camped at a distance on the plain below and gathered and trained the Gauls now flocking to his standard.[76]

Shocked by Hannibal's arrival and Scipio's setback, the Roman Senate ordered the army commanded by Tiberius Longus in Sicily to march north to assist Scipio.[76] When Longus arrived in December, Hannibal enticed him into attacking and heavily defeated him at the battle of the Trebia; only approximately 10,000 of the Roman army of 40,000 were able to fight their way off the battlefield.[77] As a result the flow of Gallic support became a flood and the Carthaginian army grew to 60,000 men.[24] Hannibal settled into winter quarters to rest and train his men,[78] while the Romans drew up plans to prevent Hannibal from breaking into Roman Italy.[79] In May 217 BC[80] the Carthaginians crossed the Apennines and provoked a Roman army into a hasty pursuit without proper reconnaissance.[81] Hannibal set an ambush[81] and in the battle of Lake Trasimene completely defeated the Roman force, killing 15,000 Romans and taking 15,000 prisoner. A cavalry force of 4,000 from another Roman army were also engaged and wiped out.[82] Hannibal campaigned in Italy for the next 12 years.[83]

In 204 BC Publius Cornelius Scipio, the same man who had fought as a youth at Ticinus, invaded the Carthaginian homeland in North Africa, defeated the Carthaginians in two major battles and won the allegiance of the Numidian kingdoms of North Africa. Hannibal and the remnants of his army were recalled from Italy to confront him.[84] They met at the battle of Zama in October 202 BC and Hannibal was decisively defeated.[85] As a consequence Carthage agreed a peace treaty which stripped it of most of its territory and power.[86]

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- 3,200 talents was approximately 82,000 kg (81 long tons) of silver.[4]

- 1,200 talents was approximately 30,000 kg (30 long tons) of silver.[4]

- The Roman army in Massala had continued to Iberia under Publius's brother, Gnaeus; only Publius had returned.[38]

- It was the settling of Roman colonists at Piacenza and Cremona that had been the cause of several of the Gallic tribes initiating their campaign against Rome earlier in the year.[21]

- This could be increased to 5,000 in some circumstances,[49] or, rarely, even more.[50]

- One of cavalry's main advantages in close combat was their impetus; they were at a considerable disadvantage if struck by opposing cavalry while stationary.[65]

- The stirrup had not been invented at the time, and Archer Jones believes its absence meant cavalrymen had a "feeble seat" and were liable to come off their horses if a sword swing missed its target.[68] Sabin states that cavalry dismounted to gain a more solid base to fight from than a horse without stirrups.[63] Goldsworthy argues that the cavalry saddles of the time "provide[d] an admirably firm seat" and that dismounting was an appropriate response to an extended cavalry versus cavalry melee. He does not suggest why this habit ceased once stirrups were introduced.[69] Nigel Bagnall doubts that the cavalrymen dismounted at all, and suggests that the accounts of them doing so reflect the additional men carried by the Gallic cavalry dismounting and that the velites joining the fight gave the impression of a largely dismounted combat.[62]

- An ancient historian writing a century after the event claimed it was a household slave, not Scipio's son, who saved him.[73] The younger Scipio was to go on to be Rome's most successful general of the war.[71]

Citations

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 82.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 157.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 97.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 158.

- Miles 2011, p. 196.

- Scullard 2006, p. 569.

- Miles 2011, pp. 209, 212–213.

- Hoyos 2015, p. 211.

- Miles 2011, p. 213.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 175.

- Miles 2011, p. 220.

- Miles 2011, pp. 219–220, 225.

- Miles 2011, pp. 222, 225.

- Bagnall 1999, pp. 146–147.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 143–144.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 144.

- Collins 1998, p. 13.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 144–145.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 145.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 139–140.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 151.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 50.

- Zimmermann 2015, p. 283.

- Zimmermann 2015, p. 284.

- Mahaney 2008, p. 221.

- Briscoe 2006, p. 47.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 41.

- Fronda 2015, p. 252.

- Zimmermann 2015, p. 291.

- Edwell 2015, p. 321.

- Lazenby 1998, pp. 43–44.

- Erdkamp 2015, p. 71.

- Hoyos 2015b, p. 107.

- Zimmermann 2015, pp. 283–284.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 168.

- Hoyos 2005, p. 111.

- Miles 2011, p. 266.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 168–169.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 52.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 169.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 169–170.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 170.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 98.

- Miles 2011, p. 268.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 32–34.

- Koon 2015, p. 80.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 32.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 48.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 23.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 287.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 48.

- Bagnall 1999, pp. 22–25.

- Lazenby 1998, pp. 50–51.

- Rawlings 1996, p. 88.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 99.

- Daly 2002, p. 13.

- Fronda 2015, p. 243.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 56.

- Sabin 1996, p. 64.

- Sabin 1996, p. 66.

- Koon 2015, p. 83.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 172.

- Sabin 1996, p. 69.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 53.

- Jones 1987, pp. 103–104, 144–145.

- Koon 2015, p. 85.

- Koon 2015, pp. 85–86.

- Jones 1987, pp. 9, 103.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 170–171.

- Koon 2015, p. 87.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 171.

- Koon 2015, p. 86.

- Hoyos 2015b, p. 108.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 173.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 172.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 173.

- Bagnall 1999, pp. 175–176.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 180.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 61.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 60.

- Fronda 2015, p. 244.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 190.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 222.

- Miles 2011, p. 310.

- Miles 2011, p. 315.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 308–309.

Sources

- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Briscoe, John (2006). "The Second Punic War". In Astin, A. E.; Walbank, F. W.; Frederiksen, M. W.; Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 B.C. Vol. VIII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–80. ISBN 978-0-521-23448-1.

- Collins, Roger (1998). Spain: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285300-4.

- Daly, Gregory (2002). Cannae: The Experience of Battle in the Second Punic War. London ; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26147-0.

- Edwell, Peter (2015) [2011]. "War Abroad: Spain, Sicily, Macedon, Africa". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 320–338. ISBN 978-1-119-02550-4.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2015) [2011]. "Manpower and Food Supply in the First and Second Punic Wars". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 58–76. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Fronda, Michael P. (2015) [2011]. "Hannibal: Tactics, Strategy, and Geostrategy". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 242–259. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2005). Hannibal's Dynasty: Power and Politics in the Western Mediterranean, 247-183 BC. London ; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35958-0.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015) [2011]. A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015b). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.

- Jones, Archer (1987). The Art of War in the Western World. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01380-5.

- Koon, Sam (2015) [2011]. "Phalanx and Legion: the "Face" of Punic War Battle". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 77–94. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Lazenby, John (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- Lazenby, John (1998). Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War. Warminster, Wiltshire: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-080-9.

- Mahaney, W.C. (2008). Hannibal's Odyssey: Environmental Background to the Alpine Invasion of Italia. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-951-7.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Rawlings, Louis (1996). "Celts, Spaniards, and Samnites: Warriors in a Soldiers' War". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement (67): 81–95. JSTOR 43767904.

- Sabin, Philip (1996). "The Mechanics of Battle in the Second Punic War". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement. 67 (67): 59–79. JSTOR 43767903.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2006) [1989]. "Carthage and Rome". In Walbank, F. W.; Astin, A. E.; Frederiksen, M. W. & Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 7, Part 2, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–569. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

- Zimmermann, Klaus (2015) [2011]. "Roman Strategy and Aims in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 280–298. ISBN 978-1-405-17600-2.