Battle of Cirta

The Battle of Cirta was fought in 203 BC between an army of largely Masaesyli Numidians commanded by their king Syphax and a force of mainly Massylii Numidians led by Masinissa, who was supported by an unknown number of Romans under the legate Gaius Laelius. It took place somewhere to the east of the city of Cirta (modern Constantine) and was part of the Second Punic War. The numbers engaged on each side and the casualties suffered are not known.

| Battle of Cirta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Masaesyli Numidians | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Syphax | |||||||

During the Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) the Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio expelled the Carthaginians from Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal) in 206 BC. Scipio then contacted several Numidian leaders, who ruled North African territories to the west of those controlled by Carthage. Scipio failed to win over the Masaesyli Numidian king Syphax, who had previously fought the Carthaginians; but did persuade the Massylii Numidian prince Masinissa, whom he had fought against in Iberia, to defect to the Roman cause. Encouraged by the Carthaginians, Syphax overran Masinissa's lands and drove him into exile. In 204 BC the Romans, led by Scipio, invaded North Africa. Masinissa rode to support them with a small force. Syphax brought a large army to assist Hasdrubal Gisco's Carthaginians. After several months Scipio inflicted a heavy defeat on Hasdrubal and Syphax at the battle of Utica. The pair regathered their forces but were defeated again at the battle of the Great Plains. Masinissa's forces fought alongside the Romans in both battles.

Syphax fled back to his capital, Cirta, and hastily raised a new army. Masinissa pursued, together with a Roman force under Scipio's second-in-command, Laelius. Masinissa and Laelius pressed for an immediate battle, but when they achieved this Syphax's troops initially had the better of the fighting. As increasing numbers of Roman infantry entered the fray, Syphax's men were first held off and then broke and fled. Syphax was captured. Masinissa took his cavalry to Cirta, which surrendered when Syphax was paraded in chains. The following year Scipio defeated Hannibal at the battle of Zama, which effectively ended the war. Masinissa was installed as king of all of Numidia.

Background

The First Punic War was fought between the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC: Carthage and Rome.[1] The war lasted for 23 years, from 264 to 241 BC, before the Carthaginians were defeated.[2][3] It took place primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily, its surrounding waters and in North Africa.[1]

From 236 BC Carthage expanded its territory in Iberia, (modern Spain and Portugal).[4] In 226 BC the Ebro Treaty with Rome established the Ebro River as the northern boundary of the Carthaginian sphere of influence.[5] A little later Rome made a separate treaty of association with the city of Saguntum, well south of the Ebro.[6] In 219 BC Hannibal, the de facto ruler of Carthaginian Iberia, led an army to Saguntum and besieged, captured and sacked it.[7][8] In early 218 BC Rome declared war on Carthage, starting the Second Punic War.[9]

Hannibal led a large Carthaginian army from Iberia, through Gaul, over the Alps and invaded mainland Italy in late 218 BC. During the next three years Hannibal inflicted heavy defeats on the Romans at the battles of the Trebia, Lake Trasimene and Cannae.[10] Hannibal's army campaigned in Italy for 14 years before the survivors withdrew.[11]

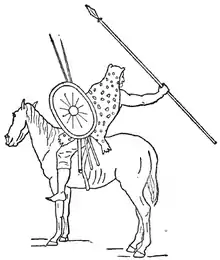

There was also extensive fighting in Iberia from 218 BC. In 210 BC Publius Cornelius Scipio arrived to take command of Roman forces in Iberia.[12] During the following four years Scipio repeatedly defeated the Carthaginians, driving them out of Iberia in 206 BC.[13] One of Carthage's allies in Spain was the Numidian prince Masinissa, who led a force of light cavalry in several battles.[14][15] These Numidians were mostly lightly-equipped skirmishers who threw javelins from a distance and avoided close combat.[16][17]

Numidian alliances

To the west of Carthaginian-controlled territory in North Africa was an extensive area controlled by shifting alliances of Numidians. Adjacent to territory where Carthage had a strong influence was an area controlled by a tribal alliance known as the Massylii, centred around the towns of Zama and Thugga. Further west was the much larger kingdom of the Masaesyli, whose capital was at Cirta (modern Constantine). The Carthaginians maintained several garrisons in these areas in an attempt to exert their influence, but largely relied on diplomacy.[18]

In 213 BC Syphax, the powerful king of the Masaesyli Numidians, declared for Rome. In response Carthaginian troops were sent to North Africa from the active theatre in Spain.[11][19] In 206 BC the Carthaginians ended this drain on their resources by dividing several small Numidian kingdoms with Syphax. One of those disinherited was the Massylii Numidian prince Masinissa.[20] Scipio was already anticipating an invasion of North Africa and while in Iberia had been negotiating with both Masinissa and Syphax.[21]

Scipio visited Syphax in North Africa in 206 BC – at the same time as the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal Gisco, whom Scipio had defeated in Spain, was attempting to reinforce Syphax's loyalty.[22][20] Scipio failed to win over Syphax,[22] who reaffirmed his support for Carthage and symbolised this by marrying Hasdrubal's daughter Sophonisba.[23] It had previously been arranged that Sophonisba was to marry Masinissa.[20] A succession war broke out among the Massylii, part of the near-constant petty wars between the various Numidian tribes, factions and kingdoms. The Carthaginians encouraged Syphax to invade the home territory of the Roman-supporting Masinissa.[24][25] Masinissa suffered several defeats, was wounded and had his army scattered; Syphax took over his kingdom.[26]

Prelude

In 206 BC Scipio returned to Italy.[29] He was elected to the senior position of consul in early 205 BC, despite not meeting the age requirement.[22] Opinion was divided in Roman political circles as to whether an invasion of North Africa was excessively risky. Hannibal was still on Italian soil; there was the possibility of further Carthaginian invasions,[30] shortly to be realised when Mago Barca landed in Liguria;[31] the practical difficulties of an amphibious invasion and its logistical follow up were considerable; and when the Romans had invaded North Africa in 256 BC during the First Punic War they had been driven out with heavy losses, which had re-energised the Carthaginians.[32] Eventually a compromise was agreed: Scipio was given Sicily as his consular province,[33] which was the best location for the Romans to launch an invasion of the Carthaginian homeland from and then logistically support it, and permission to cross to Africa on his own judgement.[30] But Roman commitment was less than wholehearted; Scipio could not conscript troops for his consular army, as was usual, only call for volunteers.[31][34]

The total number of men available to Scipio and how many of them travelled to Africa is unclear; the ancient historian Livy gives totals for the invasion force of either 12,200, 17,600 or 35,000. Modern historians estimate a combat strength of 25,000–30,000, of whom more than 90 per cent were infantry.[35][36] With up to half of the complement of his legions being fresh volunteers, and with no fighting having taken place on Sicily for the past five years, Scipio instigated a rigorous training regime, which lasted for approximately a year.[37] Roman ships under Scipio's second-in-command, Gaius Laelius, raided North Africa around Hippo Regius, gathering large quantities of loot and many captives.[38][36] Masinissa was contacted, he expressed dismay regarding how long it was taking the Romans to complete their preparations and land in Africa.[24]

Invasion of Africa

In 204 BC, probably June or July, the Roman army disembarked at Cape Farina in North Africa, 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of the large Carthaginian port of Utica.[39] Masinissa joined the Romans with either 200 or 2,000 men, the sources differ. He and his men hoped to use an alliance with Rome to recover Masinissa's kingdom from Syphax. A fortified camp was established very close to Utica.[40] Two large reconnaissance forces, consisting of both Carthaginians and Numidians were heavily defeated; the second because of the involvement of Masinissa's cavalry. The Romans pillaged an ever-wider area, sending their loot and prisoners to Sicily in the ships bringing their supplies.[41]

Scipio then besieged Utica. The city stood firm and a Carthaginian army under Hasdrubal set up a fortified camp 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from the Romans with a reported 33,000 men. Syphax joined him, establishing his own camp 2 kilometres (1 mi) away with a reported 60,000 troops. The size of both of these armies as reported by ancient historians have been questioned by their modern counterparts as being infeasibly large. Nevertheless, it is accepted that the Romans were considerably outnumbered.[42]

The presence of these two armies forced Scipio to lift the siege of Utica after forty-five days and withdraw to a strong position 3 kilometres (2 mi) away on a rocky prominence at Ghar el-Melh,[40] which became known as Castra Cornelia.[41] Scipio sent emissaries to Syphax in an attempt to persuade him to defect. Syphax in turn offered to broker peace terms to end the war. A series of exchanges of negotiating parties followed. With his delegations Scipio sent junior officers disguised as slaves to report back on the layout and construction of the enemy camps. Scipio drew out the negotiations with Syphax, stating that he was in broad agreement with the proposition, but that his senior officers were not yet convinced.[42]

Battle of Utica

As the better weather of spring approached, Scipio made an announcement to his troops that he would shortly attempt to storm the defences of Utica and began preparations to do so. Simultaneously he was planning a night attack on both enemy camps. On the night of the attack two columns set out: one was commanded by Laelius, the Roman army's second in command. This force consisted of about half the Romans and was accompanied by Masinissa's Numidians. Its target was Syphax's camp. Scipio led the balance of the Roman force against the Carthaginian camp.[43][44]

Thanks to the careful prior reconnoitring both forces reached the positions from which they were to start their attacks without issue, while Masinissa's Numidian cavalry positioned themselves in small groups so as to cover every route out of the two enemy camps. Laelius's column attacked first, storming the camp of Syphax's Numidians and concentrating on setting fire to as many of their reed and thatch barracks as possible. The camp dissolved into chaos, with many of its Numidian occupants oblivious of the Roman attack and thinking the barracks had caught fire accidentally.[45][46]

The Carthaginians heard the commotion and saw the blaze, and some of them set off to help extinguish the fire. With pre-planned coordination Scipio's contingent then attacked. They cut down the Carthaginians heading for their ally's camp, stormed Hasdrubal's camp and attempted to set fire to the wooden housing. The fire spread between the close-spaced barracks. Carthaginians rushed out into the dark and confusion, without armour or weapons, either trying to escape the flames or to fight the fire. The organised and prepared Romans cut them down. The ancient historian Polybius writes that Hasdrubal escaped from his burning camp with only 2,500 men. Numidian losses are not recorded.[45][46] With no Carthaginian field army to threaten them, the Romans resumed their siege of Utica and pillaged an extensive area of North Africa with large and far-ranging raids.[47]

Battle of the Great Plains

When word of the defeat reached Carthage there was panic, with some wanting to renew the peace negotiations. The Carthaginian Senate also heard demands for Hannibal's army to be recalled. A decision was reached to fight on with locally available resources.[48] A force of 4,000 Iberian warriors arrived in Carthage; their strength was exaggerated to 10,000 to maintain morale. Hasdrubal raised further local troops with whom to reinforce the survivors of Utica.[49] Syphax remained loyal and joined Hasdrubal with what was left of his army.[50] The combined force is estimated at 30,000 and they established a strong camp on a flat plain by the Bagradas River known as the Great Plains within 30–50 days of the defeat at Utica. This was near modern Souk el Kremis[47][49] and about 120 kilometres (75 mi) from Utica.[51]

Hearing of this, Scipio immediately marched most of his army to the scene. The size of his army is not known, but it was outnumbered by the Carthaginians.[52] A sufficient force was left to hold the Roman camps and to continue the siege of Utica.[53] After several days of skirmishing both armies committed to a pitched battle.[47] Upon being charged by the Romans and Masinissa's Numidians all of those Carthaginians who had been involved in the debacle at Utica turned and fled; morale had not recovered.[46][47][54] Only the Iberians stood and fought. They were enveloped by the well-drilled Roman legions and wiped out.[55][56] Hasdrubal fled to Carthage, where he was demoted and exiled.[57]

The majority of the Romans remained in the area under Scipio, devastating the countryside and capturing and sacking many towns. They then moved to Tunis, which had been abandoned by the Carthaginians and was only 39 kilometres (24 mi) from the city of Carthage. In desperation the Carthaginian Senate recalled both Hannibal and Mago from Italy,[58] and entered into peace negotiations with Scipio.[59] Meanwhile, Masinissa's Numidians had pursued their fleeing countrymen under Syphax; accompanied by part of the Roman force, under Laelius. The historian Peter Edwell comments that this was a high-risk enterprise.[60]

Battle of Cirta

Syphax withdrew as far as his capital, Cirta, where he recruited more troops to supplement those survivors who had stayed with him on the retreat from the Great Plains.[60] These commenced an intensive training regime. Masinissa and Laelius's force took 15 days to reach Masinissa's ancestral lands, those of the Massylii. Here Masinissa was proclaimed king and Syphax's administrators and garrisons were expelled. Not wanting to allow Syphax to train his new troops up Masinissa and Laelius pressed on towards Cirta.[61][60]

When the conflict started it was as a sprawling cavalry engagement, with each side sending detachments to hurl javelins at the other and then withdrawing. Having more cavalry, Syphax's army gained the upper hand.[60] Laelius then inserted groups of Roman light infantry between Masinissa's cavalry detachments. These infantry were velites, younger men serving as javelin-armed skirmishers; they each carried several javelins, which would be thrown from a distance, a short sword and a 90-centimetre (3 ft) shield. These were able to hold off the enemy cavalry and form an approximate battle line.[62][60] The Roman heavy infantry were then able to advance. These were equipped with body armour, a large shield and short thrusting swords, as well as either two javelins or a thrusting spear. Seeing these legionaries advancing to join the battle, Syphax's troops broke and fled.[63][60] Syphax attempted to rally his men, but his horse was shot and he was thrown and captured.[57][64]

Many of Syphax's defeated and demoralised troops fled back to Cirta. Masinissa pursued them with the cavalry; Laelius followed with the infantry. After Syphax was paraded beneath the city walls in chains Cirta surrendered to Masinissa, who then took over much of Syphax's kingdom and joined it to his own.[note 1][65][61] Syphax was taken as a prisoner to Italy, where he died.[66]

Aftermath

Scipio and Carthage entered into peace negotiations, while Carthage recalled both Hannibal and Mago from Italy.[59] The Roman Senate ratified a draft treaty, but because of mistrust and a surge in confidence when Hannibal arrived from Italy, Carthage repudiated it.[67] Hannibal was placed in command of another army, formed of his and Mago's veterans from Italy and newly raised troops from Africa, with 80 war elephants but few cavalry.[68] The decisive battle of Zama followed in October 202 BC.[23] Hannibal was supported by 2,000 Numidian cavalry commanded by a relative of Syphax's, Tychaeus. Masinissa fought alongside the Romans with 6,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.[69] After a prolonged fight the Carthaginian army collapsed. Masinissa played an important role in the Roman victory. Hannibal was one of the few on the Carthaginian side to escape the field.[23][70]

After the Romans had returned to Utica, Scipio received word that a Numidian army under Syphax's son Vermina was marching to Carthage's assistance. This was intercepted, surrounded by a Roman force largely made up of cavalry and defeated. The number of Numidians involved is not known, but Livy records that more than 16,000 were killed or captured. This was the last battle of the Second Punic War.[71][72]

Peace

The peace treaty the Romans subsequently imposed on the Carthaginians stripped them of all of their overseas territories and some of their African ones. An indemnity of 10,000 silver talents[note 2] was to be paid over 50 years. Hostages were taken. Carthage was forbidden to possess war elephants and its fleet was restricted to 10 warships. It was prohibited from waging war outside Africa and in Africa only with Rome's express permission. Masinissa was to be recognised as the ruler of all of Numidia. Many senior Carthaginians wanted to reject it, but Hannibal spoke strongly in its favour and it was accepted in spring 201 BC. Henceforth it was clear Carthage was politically subordinate to Rome.[75] Scipio was awarded a triumph and received the agnomen "Africanus".[76] Masinissa established himself as the senior ruler in Numidia.[25]

Third Punic War

Masinissa exploited the prohibition on Carthage waging war to repeatedly raid and seize Carthaginian territory with impunity. Carthage appealed to Rome, which always backed their Numidian ally.[77] In 149 BC, fifty years after the end of the Second Punic War, Carthage sent an army, under Hasdrubal the Boeotarch, against Masinissa,[note 3] the treaty notwithstanding. The campaign ended in disaster at the battle of Oroscopa and anti-Carthaginian factions in Rome used the illicit military action as a pretext to prepare a punitive expedition.[80] The Third Punic War began later in 149 BC when a large Roman army landed in North Africa[81] and besieged Carthage.[82] In the spring of 146 BC the Romans launched their final assault, systematically destroying the city and killing its inhabitants;[83] 50,000 survivors were sold into slavery.[84] The formerly Carthaginian territories became the Roman province of Africa.[85][86]

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- Masinissa also married Syphax's wife, Sophonisba, Hasdrubal's daughter.[65]

- Several different "talents" are known from antiquity. The ones referred to in this article are all Euboic (or Euboeic) talents, of approximately 26 kilograms (57 lb).[73][74] 10,000 talents was approximately 269,000 kilograms (265 long tons) of silver.[73]

- Masinissa, now aged 88, was still able to lead his army into battle and father children. He died in 148 BC.[78][79]

Citations

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 82.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 157.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 97.

- Miles 2011, p. 220.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 143–144.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 144.

- Collins 1998, p. 13.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 144–145.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 145.

- Ñaco del Hoyo 2015, p. 377.

- Edwell 2015, p. 322.

- Edwell 2015, p. 323.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 277–285.

- Edwell 2015, p. 330.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 233.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 32–34.

- Koon 2015, pp. 79–87.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 270.

- Miles 2011, p. 308.

- Barceló 2015, p. 372.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 285–286.

- Carey 2007, p. 99.

- Miles 2011, p. 315.

- Lazenby 1998, pp. 198–199.

- Kunze 2015, p. 398.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 291–292.

- Coarelli 2002, pp. 73–74.

- Etcheto 2012, pp. 274–278.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 285.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 286.

- Miles 2011, p. 306.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 286–287.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 194.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 195.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 287.

- Carey 2007, p. 100.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 287–288.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 288.

- Carey 2007, p. 103.

- Bagnall 1999, pp. 271, 275.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 292.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 292–293.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 293.

- Edwell 2015, p. 332.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 293–294.

- Edwell 2015, p. 333.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 295.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 294.

- Hoyos 2003, p. 162.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 294–295.

- Briscoe 2006, p. 63.

- Carey 2007, p. 106.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 280.

- Carey 2007, p. 108.

- Rawlings 1996, p. 90.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 295–296.

- Hoyos 2015b, p. 205.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 296–297.

- Carey 2007, p. 111.

- Edwell 2015, p. 334.

- Carey 2007, p. 110.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 48.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 50.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 282.

- Lazenby 1998, p. 212.

- Kunze 2015, p. 397.

- Bagnall 1999, pp. 287–291.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 302.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 289.

- Carey 2007, p. 118.

- Carey 2007, p. 131.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 296.

- Lazenby 1996, p. 158.

- Scullard 2006, p. 565.

- Carey 2007, p. 132.

- Miles 2011, p. 318.

- Kunze 2015, pp. 398, 407.

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 335, 345.

- Bagnall 1999, p. 15.

- Kunze 2015, pp. 399, 407.

- Purcell 1995, p. 134.

- Goldsworthy 2006, p. 341.

- Le Bohec 2015, p. 441.

- Scullard 2002, p. 316.

- Scullard 1955, p. 103.

- Scullard 2002, pp. 310, 316.

Sources

- Bagnall, Nigel (1999). The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6608-4.

- Barceló, Pedro (2015) [2011]. "Punic Politics, Economy, and Alliances, 218–201". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 357–375. ISBN 978-1-119-02550-4.

- Le Bohec, Yann (2015) [2011]. "The "Third Punic War": The Siege of Carthage (148–146 BC)". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 430–446. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Briscoe, John (2006). "The Second Punic War". In Astin, A. E.; Walbank, F. W.; Frederiksen, M. W.; Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 B.C. Vol. VIII (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–80. ISBN 978-0-521-23448-1.

- Carey, Brian Todd (2007). Hannibal's Last Battle: Zama and the Fall of Carthage. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-635-1.

- Coarelli, Filippo (2002). "I ritratti di 'Mario' e 'Silla' a Monaco e il sepolcro degli Scipioni". Eutopia Nuova Serie (in Italian). II (1): 47–75. ISSN 1121-1628.

- Collins, Roger (1998). Spain: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285300-4.

- Edwell, Peter (2015) [2011]. "War Abroad: Spain, Sicily, Macedon, Africa". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 320–338. ISBN 978-1-119-02550-4.

- Etcheto, Henri (2012). Les Scipions. Famille et pouvoir à Rome à l'époque républicaine (in French). Bordeaux: Ausonius Éditions. ISBN 978-2-35613-073-0.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-304-36642-2.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2003). Hannibal's Dynasty: Power and politics in the Western Mediterranean, 247–183 BC. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-41782-9.

- Hoyos, Dexter (2015b). Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-986010-4.

- Koon, Sam (2015) [2011]. "Phalanx and Legion: the "Face" of Punic War Battle". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 77–94. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Kunze, Claudia (2015) [2011]. "Carthage and Numidia, 201–149". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 395–411. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Lazenby, John (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- Lazenby, John (1998). Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-080-9.

- Miles, Richard (2011). Carthage Must be Destroyed. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-101809-6.

- Ñaco del Hoyo, Toni (2015) [2011]. "Roman Economy, Finance, and Politics in the Second Punic War". In Hoyos, Dexter (ed.). A Companion to the Punic Wars. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley. pp. 376–392. ISBN 978-1-1190-2550-4.

- Purcell, Nicholas (1995). "On the Sacking of Carthage and Corinth". In Innes, Doreen; Hine, Harry & Pelling, Christopher (eds.). Ethics and Rhetoric: Classical Essays for Donald Russell on his Seventy Fifth Birthday. Oxford: Clarendon. pp. 133–148. ISBN 978-0-19-814962-0.

- Rawlings, Louis (1996). "Celts, Spaniards, and Samnites: Warriors in a soldier's war". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement. The Second Punic War: A Reappraisal. London: Institute of Classical Studies/Oxford University Press. 2 (67): 81–95. ISSN 2398-3264. JSTOR 43767904.

- Scullard, Howard (1955). "Carthage". Greece & Rome. 2 (3): 98–107. doi:10.1017/S0017383500022166. JSTOR 641578. S2CID 248519024.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2002). A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30504-4.

- Scullard, Howard H. (2006) [1989]. "Carthage and Rome". In Walbank, F. W.; Astin, A. E.; Frederiksen, M. W. & Ogilvie, R. M. (eds.). Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. VII, part 2 (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–569. ISBN 978-0-521-23446-7.

_-_Glyptothek_-_Munich_-_Germany_2017.jpg.webp)