Battle of Veere

The Battle of Veere was a small naval battle that took place in late May 1351 during the Hook and Cod wars.

| Battle of Veere | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Hook and Cod wars | |||||||||

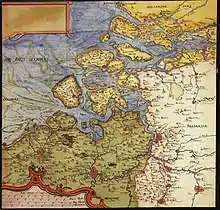

Map of Veere in about 1570 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Hook faction England | Cod faction | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| William V of Holland | |||||||||

Context

Just like the County of Holland, the County of Zeeland had been very restive after the death of the last male Avesnes count William IV of Holland and Zeeland. In 1349-1350 William of Bavaria attempted to become count of Holland and Zeeland without keeping the conditions his mother Margaret, Countess of Hainaut had demanded.

In April 1350 William went to Hainaut and submitted to his mother, and that seemed the end of William's rule. However, in August 1350 an assassination led to open rebellion.[2] Delft, a number of other cities north of the Hollandse IJssel and some nobles formed an alliance later known as the Cod faction. They attacked the perpetrators, and refused to submit to Margaret's authority.[3]

In order to secure her authority in Zeeland, Margaret travelled from Zierikzee to Middelburg. On 18 January 1351 Wolfert III van Borselen, Claas van Borselen, Floris van Borselen and Olivier van Everingen pledged their loyalty to her.[4] Jan and Florens van Haamstede and their allies did the same.[5]

In the night of 1-2 February 1351 William escaped from Hainaut. He appeared in Holland a few days later, and placed himself at the head of the Cod faction. Margaret was supported by the Hook faction.

Margaret next went to Dordrecht, where her older son Louis also arrived.[6] Here Margaret tried to gather support, but meanwhile William's rule became ever more solid. Margaret then sent repeated invitations to William to negotiate in Dordrecht, but he refused to appear. In late March or early April Margaret then left for the (English) city of Calais to gather support from England.[7][8]

The strategic Situation

Holland, April 1351

William was supported by the Cod faction. This consisted of most of the cities in Holland, and a small part of the nobility. Of the cities in Holland some, like Delft, Haarlem, Leiden, Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Schiedam were fierce supporters of William.[9] Others cities might have been lukewarm. Only a small part of the nobility supported the Cods, and these were not the mightiest lords. Margaret's Hook side was supported by the small cities Gouda and Schoonhoven and held Geertruidenberg. It had many supporters among the nobility. Its leadership consisted of some high nobles with well fortified castles.

After the failed negotiations of April 1351, many Hook lords had withdrawn to their castles. The Hook leadership was with Margaret. William was not able to quickly take all of the Hook castles. He started to besiege some, while other castles were left alone. As the Hook side was evidently unable to stop William, this would in time lead to William becoming master of all the Hook castles. Therefore, Margaret had to act.

The situation in Zealand

Margaret was in control of Zierikzee, the second city of Zeeland, located on the island Schouwen. The city had been very rebellious some years before, but now seemed solidly on her side. On the island she was supported by Jan II van Haamstede lord of Haamstede and his brother Floris II van Haamstede, owners of Haamstede Castle.

The other big city in Zealand was Middelburg on the island of Walcheren. The mightiest lord of Walcheren was Wolfert van Borselen, the enemy of the Haamstede's. He was Lord of the recently fortified small city of Veere and resided on the nearby castle Zandenburg.

Another mighty lord in Zeeland was Machteld van Voorne. She was lady of Voorne, and controlled the islands Voorne and Goeree. On Voorne was her ancestral home the Burcht of Voorne, which she held as burgrave of Zeeland. Margaret had alienated Machteld by granting Machteld's lands to her son Otto V, Duke of Bavaria upon her death, which made that Machteld would do anything to help William.[10]

Margaret's alliance with Edward III

Already in October 1350 Margaret had started negotiations with Edward III of England. The idea was that he would use force to take control in Holland, Zeeland and Friesland, and would be compensated by getting temporary custody of the area.[11][8]

After the failed negotiations in Dordrecht, Margaret again sought aid in England. Edward III of England was married to Margaret's sister Philippa of Hainault, and therefore had some pretention to possibly inherit Holland, Zeeland and Hainaut. He was especially interested in Zeeland, which was useful for his trade relations with the County of Flanders.[12]

As stated above, Margaret left Dordrecht in late March or early April. She went to Calais to meet the English representatives: Queen Philippa, Henry Duke of Lancaster, and Walter Manny, 1st Baron Manny. Monsieur d'Enghien (from Hainaut) was also with her.[13]

As these people were meeting in Calais, Margaret received news that on 16 April William had been recognized as count by Dordrecht. The English representatives pledged to aid Margaret, who went to Hainaut to gather support there.[14]

The battle

Wolfert van Borselen revolts near Middelburg

2.JPG.webp)

After arriving back in Hainaut, a delegation of her supporters and the government of Zierikzee arrived, carrying letters by her son Louis. They pointed out that she had to come to Zierikzee, or loose Zeeland too. Wolfert III van Borselen, lord of Veere was assembling an army near Middelburg, and had invited William to come over.[14] It led to Middelburg switching to William's side.

Margaret now hurried northwards to the now disappeared city of Reimerswaal, on the southern bank of the Eastern Scheldt. Here she met her son Louis.[15]

Summary of events

Not much is known about the battle. It is said that an English fleet came to Zeeland, and united with Margaret's army. William also sent a fleet, and near Veere the battle was fought. Van Borselen died soon after.[8]

In an old chronicle printed in 1517 the battle was described as follows: She (Margaret) collected a choice army to fight against her own son. The queen of England also sent her sister a good army, carefully selected and experienced in the art of war. When both armies were ready to fight, the empress (i.e. Margaret) was in command of a large group of ships that had been made ready for combat. With many flags and trumpets this fleet arrived before the city of Veere on Walcheren.[16]

From his side Duke (i.e. count) William collected many soldiers in Holland, and on ships, these arrived in Zeeland to fight his mother. When these two forces met, there was fierce fighting, and many casualties on both sides. Many were drowned. In the end, the empress won. Duke William managed to escape and arrived back in Holland. This happened in 1351.[16]

A credible, but vague description is in the medieval parchment recovered by Van den Bergh.[15] After joining forces at Reimerswaal, Margaret and Louis attempted to do battle with Wolfert van Borselen. Part of Wolfert's army then deserted him, and Wolfert retreated. While on his way, Wolfert met Count William, and both went to Middelburg. Wolfert then became ill and died, and William went back to Holland. Margaret and Louis went to Zierikzee, where they met Walter de Manny and the English.[17]

The battle in Dutch Historiography

The above was the prevailing version of events in the Dutch Historiography about the Battle of Veere. About 250 years after the above chronicle, the historian Wagenaar told the same story.[18] In about 1812 the historian Van Wijn performed some research about the battle.[19] The reason was that some doubted whether the Battle of Veere had actually taken place. The primary reason was that some writers did not mention the battle of Veere, but did mention the later Battle of Zwartewaal. Johannes de Beke's almost contemporary Chronicle of the County of Holland and Bishopric of Utrecht is one of these.

Van Wijn solved some doubts about the battle by pointing to two documents by Margaret. One of 24 June 1315 and one of 29 June 1351, respectively referring to a battle 'at Arnemuiden',[20] and 'between Arnemuiden and Veere'.[21] Van Wijn then continued about whether it would have been a land battle or a sea battle. He found that Johan Reygersberg called it a sea battle, and others a land battle. Van Wijn choose to believe Reygersberg, because he was a local historian, who might have seen unknown sources. Reygersberg stated that the fight was between Veere and Arnemuiden, near the Vingerling of Der Veere.[22][23]

In 1838 Laurens Philippe Charles van den Bergh started an investigation of the archives in Lille, France. This led to the discovery of the parchment written in Medieval French labeled No. XCVII. Verhaal van den oorsprong der Hoeksche en Kabeljauwsche twisten. It seems a contemporary account written by somebody who also knew to write Dutch and was close to Margaret. It might have been made for informing the English mediators.[24]

The date of the battle

Van Wijn also investigated the date of the battle. He put it at between 26 and 30 May 1351.[1]

Results

The same late June documents that refer to the battle also refer to some people from Domburg having to serve against Margaret's enemies in Middelburg.[20] Blok states that the result of the battle was that Middelburg and the whole of Zeeland came under Margaret's authority.[8]

The unknown author of Van den Bergh states that after the battle, Margaret and Louis went to Zierikzee. This seems strange, but without siege equipment they could do little against Middelburg. Afterwards they sent Walther de Manny, d'Enghien and Estievene Mauleon to Middelburg to summon the city to submit. However, these emissaries had to run for their lives, because the furious commoners only wanted to acknowledge Count William.[17]

Margaret's victory at Veere therefore seems rather limited. However, she did prevent Count William from taking control of the whole of Walcheren, which would have seriously threatened her position at Zierikzee. She also gained some allies, notably the lords of Heenvliet on the south bank of the Meuse.[25]

Meanwhile the battle did not prevent the fall of several castles in Holland to William. He even started and completed the Siege of Polanen Castle in June. The defeat probably did interrupt or stall the siege of Brederode Castle. William now had to focus on rebuilding a fleet and army, and was probably prevented from starting major sieges.

Margaret had gained a tactical victory. However, in essence she still had to act quickly if she wanted to save her remaining Hook allies in Holland. This led to her attempt at invasion by the Meuse, leading to her defeat in the Battle of Zwartewaal.

References

- Aurelius, Cornelis; De Hamer, Aarnoud (2011), Die cronycke van Hollandt, Zeelandt ende Vrieslant, met die cronike der biscoppen van Uutrecht (Divisiekroniek), HES Uitgevers, Utrecht

- Van den Bergh, L.Ph.C. (1842), "No. XCVII. Verhaal van den oorsprong der Hoeksche en Kabeljauwsche twisten", Gedenkstukken tot opheldering der Nederlandsche geschiedenis opgezameld uit de archiven te Rijssel (in French), Luchtmans, Leiden, pp. 198–240

- Blok, P.J. (1923), Geschiedenis van het Nederlandsche Volk, vol. I, A.W. Sijthoff's, Leiden

- De Jonge, J.C. (1817), Verhandeling over den Oorsprong der Hoeksche en Kabeljauwsche Twisten (PDF), H.W. Hazenberg, Leiden

- Van Mieris, Frans (1754), Groot charterboek der graaven van Holland, van Zeeland, en heeren van Vriesland, vol. II, Pieter vander Eyk, Leyden

- Prevenier, W.; Smit, J.G. (1991), Bronnen voor de geschiedenis der dagvaarten van de Staten en steden van Holland, vol. I, Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis

- Reygersberg, Johan (1551), Dye Cronijcke van Zeelandt

- Wagenaar, Jan (1770), Vaderlandsche historie, vol. III, Isaak Tirion, Amsterdam

- Van Wijn, Hendrik (1812), "Iets nopens Heer Diederik, Heer van Brederode, en de Water- en Landslagen, tussen Hertog Willem van Beieren, en zijn moeder keizerin Margareta", Huiszittend Leeven, bevattende eenige mengelstoffen betrekkelijk tot de letter-, historie- en oudheid-kunde van Nederland, Johannes Allart, Amsterdam, vol. II

Notes

- Van Wijn 1812, p. 257.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 213.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 217.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 223.

- Van Mieris 1754, p. 767.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 224.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 225.

- Blok 1923, p. 325.

- Prevenier & Smit 1991, p. 78.

- De Jonge 1817, p. 65.

- Van Mieris 1754, p. 786.

- Blok 1923, p. 321.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 226.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 227.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 228.

- Aurelius & De Hamer 2011, p. 213v.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 229.

- Wagenaar 1770, p. 279.

- Van Wijn 1812, p. 240.

- Van Mieris 1754, p. 797.

- Van Mieris 1754, p. 798.

- Reygersberg 1551.

- Van Wijn 1812, p. 246.

- Van den Bergh 1842, p. 198.

- Van Mieris 1754, p. 799.