Battle of St. Pölten

The Battle of St. Pölten was the decisive engagement between Austrian and Franco-Bavarian forces, which would turn the tide of the 1741 Austrian campaign.

| Battle of St. Pölten | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of Austrian Succession | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000 | 22,000 | ||||||

Background

In 1740 Frederick the Great invaded Silesia and defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Mollwitz.[1] The Habsburg monarchy was originally subject to Salic law, which excluded women from inheriting it; the 1713 Pragmatic Sanction set this aside, allowing Maria Theresa to succeed her father.[2] However, since it made clear that Austria was too weak to defend all of its territories, several European countries created a pact known as the League of Nymphenburg to partition and destroy Austria once for all.[3]

The situation was dire for Austria. French and Bavarian troops invaded Upper Austria while at the same time 20,000 Saxons entered Bohemia.[4] To make matters only worse, in the second half of November 1741, 10,000 Spanish troops had landed at Orbitello, plus sixteen more battalions at Lerici and La Spezia, and a supply of twelve battalions and 4,500 horses were still expected. All in all, the number of the combined Spaniards and Neapolitans was over 26,000 men, which Traun had to oppose all in all only 9,500 infantry and 2,400 cavalry. Sardinia meanwhile, part of the League of Nymphenburg, could possibly invade Austrian Lombardy with the Duke of Modena joining the enemy side as well.[5]

Battle

While in Vienna the entire population was occupied with military detention, almost at the same time large numbers of troops quickly gathered in the neighboring regions of Hungary and Croatia to provide assistance. Time learned this the enemy and this was the main reason he imposed the siege of Vienna, which were undoubtedly planned at the beginning of the war was, gave up against hope. Maria Theresa had as soon as she left Vienna for Pressburg and then Budapest had come, the estates of all Hungary convened and she, while painful tears streamed from her eyes, around hers. Through this spectacle the Hungarians became so excited that they all together shouted that they would rise to their aid, the sooner, the better. Only 22,000 of 60,000 troops could be initially called up for service, but Khevenhüller promised Maria Theresa that it sufficed to expel the invaders.[6]

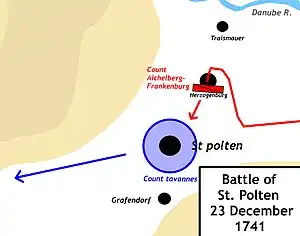

The Hungarian cavalry led by Khevenhüller, appeared shortly after the French had been mustered at St. Pölten on 23 December 1741. On this occasion, the Hungarians came in a roundabout way and in the middle of the night unexpectedly from Herzogenurg into the area of St. Pölten and, they took advantage by surprising the French and attacked the enemy camp with great speed. After cutting down several French troops, the Hungarians lead a cavalry standard, some spoils to attack the Count Tavannes, a noble Frenchman, along with some common French soldiers. This happened on high noon and through this outcome of things spread in the whole city and in the camp an immense consternation and Confusion. The gates of the city were immediately cleared by the guards closed, some regiments under arms summoned to combat with the Hungarians determined the battle. Meanwhile, however, Khevenhüller's subordinate officer Menzel was with his Hungarians and the booty with the loss of a single man.

On the occasion proved the big difference between the Hungarian and French horseman. Because although the French, just like the Hungarian army, were made into squadrons, it turned out in the fighting that followed, the Hungarian cavalry was much better than the French. Tavannes was taken to Vienna as a prisoner brought, and since it was known that he was the Bavarian elector was very dear, he was immediately restored to his former freedom and dismissed. The battle ended with the French escaping from St. Pölten.[7]

Aftermath

The battle turned the war into Austria's favor. Khevenhüller defeated on 17 January 1742 a Bavarian army at Schärding; a week later, 10,000 French soldiers capitulated at Linz after brief fighting. Although Charles Albert of Bavaria was crowned as Charles VII, the next Holy Roman Emperor and first non-Habsburg in 300 years to accede that throne, the Bavarian capital Munich was captured at the same time.

Furthermore, the Austrian commander, Count Otto Ferdinand von Traun had out-marched the 40,000 strong Spanish-Neapolitan army, captured Modena and forced the Duke to make a separate peace.[8] On 1 February 1742, Schulenburg and Ormea signed the Convention of Turin which resolved (or postponed resolution) many differences and formed an alliance between the two countries with Sardinia officially switching sides.[9]

However, Frederick the Great defeated the Austrians again at the Battle of Chotusitz, signing the Treaty of Breslau and recognizing the humiliating permanent loss of Silesia to Prussia.[10]

References

- Longman 1895, p. 117; Pratt 1956, p. 209.

- Anderson 1995, p. 3.

- Clark 2006, pp. 193–194.

- Asprey 1986, p. 223.

- Von Duncker, Carl (1894). Abensberg und Traun, Otto Ferdinand Graf von. p. 509.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Anderson 1995, p. 86.

- SCHWERDFEGER, JOSEF. DIE AUFZEICHNUNGEN DBS ST. PÖLTENER CHORHERRN AQUILIN JOSEPH HACKER ÜBER DEN EINFALL KARLS VII. (KARL ALBRECHTS) IN ÖSTERREICH, 1741 BIS 1742. JOSEF SCHWERDFEGER.

- Hannay 1911, p. 40.

- Browning 2005, p. 97.

- Showalter 2012, p. 27.

Sources

- Anderson, Mark (1995). "The Prussian Invasion of Silesia and the Crisis of Habsburg Power". The War of the Austrian Succession. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582059504.

- Asprey, Robert B. (1986). "The First Silesian War, 1740-1742". Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma. New York: Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 978-0-89919-352-6.

(registration required)

(registration required) - Browning, Reed (2005). "New Views on the Silesian Wars". The Journal of Military History. 69 (2): 521–534. doi:10.1353/jmh.2005.0077. JSTOR 3397409. S2CID 159463824.

(registration required)

(registration required) - Clark, Christopher (2006). "Struggle for Mastery". Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02385-7.

(registration required)

(registration required) - This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hannay, David (1911). "Austrian Succession, War of the". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–45.

- Longman, Frederick (1895). "The Conquest of Silesia". Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' War. F. W. Longman.

- Pratt, Fletcher (1956). "Frederick the Great and the Unacceptable Decision". The Battles that Changed History: From Alexander the Great to Task Force 16. Garden City, NY: Hanover House.

(registration required)

(registration required) - Showalter, Dennis (2012). Frederick the Great: A Military History. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1848326408.