Battle of Gang Toi

The Battle of Gang Toi (8 November 1965) was fought during the Vietnam War between Australian troops and the Viet Cong. The battle was one of the first engagements between the two forces during the war and occurred when A Company, 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR) struck a Viet Cong bunker system defended by Company 238 in the Gang Toi Hills, in northern Bien Hoa Province. It occurred during a major joint US-Australian operation codenamed Operation Hump, involving the US 173rd Airborne Brigade, to which 1 RAR was attached. During the latter part of the operation an Australian rifle company clashed with an entrenched company-sized Viet Cong force in well-prepared defensive positions. Meanwhile, an American paratroop battalion was also heavily engaged in fighting on the other side of the Song Dong Nai.

| Battle of Gang Toi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

.PNG.webp) Second Lieutenant Clive Williams during orders with his section commanders. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120 men | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

6 killed 5 captured | ||||||

The Australians were unable to concentrate sufficient combat power to launch an assault on the position and consequently they were forced to withdraw after a fierce engagement during which both sides suffered a number of casualties, reluctantly leaving behind two men who had been shot and could not be recovered due to heavy machine-gun and rifle fire. Although they were most likely dead, a battalion-attack to recover the missing soldiers was planned by the Australians for the next day, but this was cancelled by the American brigade commander due to rising casualties and the need to utilise all available helicopters for casualty evacuation. The bodies of the two missing Australian soldiers were subsequently recovered more than 40 years later, and were finally returned to Australia for burial.

Background

Military situation

Although the initial American commitment to the war in Vietnam had been limited to advice and materiel support, by 1964 there were 21,000 US advisors in South Vietnam.[1] However, with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) weakened by successive defeats at the hands of the communists, the South Vietnamese government faltering, and Saigon threatened with a major offensive, the situation led to a significant escalation of the war in 1965, with a large-scale commitment of US ground troops under the command of General William Westmoreland.[2] At first the Americans had adopted a cautious strategy, applied to the strictly limited role of base defence by US Marine units. This was abandoned in April 1965, and replaced by a new "enclave strategy" of defending key coastal population centres and installations.[3] This strategy required the introduction of nine additional US battalions, or 14,000 troops, to bring the total in Vietnam to 13. Allied nations of the Free World Military Forces were expected to contribute another four battalions.[4]

Westmoreland planned to develop a series of defensive positions around Saigon before expanding operations to pacify the South Vietnamese countryside and as a result a number of sites close to Viet Cong dominated areas were subsequently chosen to be developed into semi-permanent divisional-level bases. Such areas included Di An which was intended to become the headquarters of the US 1st Infantry Division, while the US 25th Infantry Division would be based in the vicinity of Cu Chi. However, large-scale military operations to clear the intended base areas had to wait until the dry season.[5] Yet the allied enclave strategy proved only transitory and further setbacks led to additional troop increases to halt the losing trend.[6] With the situation reaching a crisis point during the Viet Cong wet season offensive in June 1965, Westmoreland requested further reinforcement and US and allied forces increased to 44 battalions which would be used to directly bolster the ARVN.[7]

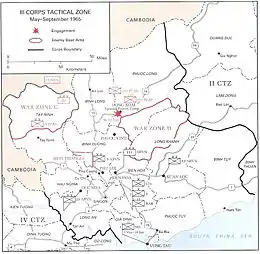

Australia's growing involvement in Vietnam reflected the American build-up. In 1963, the Australian government had committed a small advisory team, known as the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV), to help train the South Vietnamese forces.[8] However, in June 1965 the decision to commit ground troops was made, and the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment—originally commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ivan 'Lou' Brumfield—was dispatched. Supporting 1 RAR was the 1 Troop, A Squadron, 4th/19th Prince of Wales's Light Horse equipped with M113 armored personnel carriers, artillery from the 105th Field Battery, Royal Australian Artillery and 161st Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery, and 161st Reconnaissance Flight operating Cessna 180s and Bell H-13 Sioux light observation helicopters; in total 1,400 personnel.[9][10] The Australian units and New Zealand artillery were attached to the US 173rd Airborne Brigade under the command of Brigadier General Ellis W. Williamson in Bien Hoa and operated throughout the III Corps Tactical Zone (III CTZ) to help establish the Bien Hoa–Vung Tau enclave.[11][12] Although logistics and resupply were primarily provided by the Americans, a small logistic unit—1st Australian Logistics Company—was situated at Bien Hoa airbase.[9] Unlike later Australian units that served in Vietnam, which included conscripts, 1 RAR was manned by regular personnel only.[8]

Attached to US forces, 1 RAR was primarily employed in search and destroy operations using the newly developed doctrine of airmobile operations, utilising helicopters to insert light infantry and artillery into an area of operations, and to support them with aerial mobility, fire support, casualty evacuation, and resupply.[13] The battalion commenced operations in late June 1965 and initially focussed on defeating the Viet Cong's wet season offensive. During this time US 173rd Brigade, including 1 RAR, conducted a number of operations into War Zone D—a major communist base area at the junction of Phuoc Long, Long Khanh, Bien Hoa and Binh Duong provinces—as well as in the Iron Triangle in November.[14]

Prelude

Opposing forces

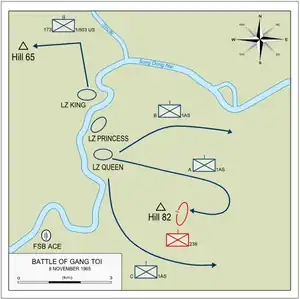

By late-1965 the junction of the Song Be and Song Dong Nai rivers had become a major communist staging area for men, equipment, and supplies for units based around Saigon and the Mekong Delta. Communist communications and resupply routes between War Zone C and D also met in this area. Westmoreland planned to use the US 173rd Airborne Brigade to keep the Viet Cong off balance and to target their base areas, and consequently a search-and-destroy operation codenamed "Operation Hump" was planned.[15] Operation Hump marked the half-way point in the twelve-month tour of duty of the 173rd Airborne Brigade and was named accordingly.[16] The concept of operations envisioned 1 RAR and the US 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment being inserted by helicopter during an airmobile operation into War Zone D, in an area about 20 kilometres (12 mi) north-east of the Bien Hoa Air Base. The Australian and American area of operations (AO) was to be separated by the Song Dong Nai, with 1 RAR to deploy into a landing zone (LZ) to the south, while the 1/503rd would conduct a helicopter assault onto a LZ northwest of the Song Dong Nai and Song Be.[17] Meanwhile, the 173rd Airborne Brigade's second battalion—2nd Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment—would be left to defend Bien Hoa Air Base.[16]

The area was thought to be a Viet Cong stronghold and American intelligence initially identified Q762 Main Force Regiment and D800 Main Force Battalion as being nearby.[18] However, unknown to the allied force, the Viet Cong 9th Division had likely received forewarning of the operation and had deployed one of its most experienced regiments, supported by a number of local force battalions, determined for a test of allied strength.[15] The 271 Main Force Regiment (also known as Q761 Main Force Regiment) subsequently took up defensive positions in the area, while the communist U1 headquarters protected by Company 238, was situated on the plateau atop the Gang Toi Hills in an area which formed part of 1 RAR's objective.[19][18] U1 was responsible for co-ordinating the Viet Cong regional defence against the Bien Hoa air base and for developing anti-government resistance and had been tasked with rebuilding the covert organisation in Bien Hoa city and the surrounding villages up to the Dong Nai, as well as re-establishing the link between Bien Hoa city and War Zone D, and for planning and executing attacks against the air base itself. Yet having relocated to the rainforest two months earlier, its presence was also unknown to the Australians and Americans.[20] Regardless, A Company 1 RAR was scheduled to conduct a search of the plateau on the fourth day of the operation.[21]

Battle

Insertion and patrolling, 5–7 November 1965

On 5 November 1 RAR began the routine search-and-destroy operation, inserting by helicopter south of the Song Dong Nai at 08:00, while the 1/503rd was inserted onto LZ King north-west of the Song Dong Nai and Song Be rivers at 11:00.[17] The operation started badly for the Australians and Americans with the fly-in delayed. Despite a lengthy preparation by fire, a large Viet Cong force had been observed in the vicinity of LZ Queen prior to the insertion of the lead Australian rifle company—D Company under the command of Captain Peter Rothwell. The escorting helicopter gunships began taking small arms fire as they attempted to provide suppressing fire and Rothwell made the decision to activate the alternate landing zone to the north-east, LZ Princess. D Company was subsequently inserted safely and swept back to LZ Queen, securing it for the remainder of the battalion. By mid-morning 1 RAR occupied LZ Queen, with the 105 mm L5 pack howitzers of 105 Field Battery also flying-in to provide direct support.[22] Augmenting the Australian gunners, the US 3/319 Artillery Battalion and 161st Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery occupied FSB Ace 4,000 metres (4,400 yd) further south.[23]

The scheme of manoeuvre adopted by 1 RAR dictated that each company undertake a dispersed patrol program in their own tactical area of responsibility, a fact which would allow them to search more ground, but limit their ability to concentrate combat power in the event of contact. A Company, under Major John Healy, patrolled east; B Company moved north along the Song Be to Xom Xoai, while D Company patrolled south.[23] C Company remained at LZ Queen to protect 105 Field Battery which had established a fire support base (FSB).[24] Over the next two days the Australians patrolled relentlessly through the leech-infested swamps and dense jungle.[23] At midday on 6 November A Company received two mortar rounds which failed to do any damage, but marked the start of a series of minor clashes.[24] A Company had a number of contacts during this time, with the Australians killing a Viet Cong scout for the loss of two wounded in one skirmish. A further contact soon after resulted in two more Viet Cong killed and one wounded. Intelligence gained from these incidents indicated the presence of a Viet Cong Main Force Regiment in the area, while documents recovered contained plans for attacks on ARVN outposts near Bien Hoa Air Base.[23]

By nightfall on 7 November, despite the earlier contacts, no major actions had occurred in the Australian AO. With the rifle companies now several kilometres apart, A Company had patrolled into a network of well used roads and tracks. Healy's men spent the night astride the tracks and would resume patrolling the following day along a track which led to Hill 82.[23][25] Meanwhile, although unknown to them at the time, the US 1/503rd Battalion across the Song Dong Nai had patrolled to within 2,000 metres (2,200 yd) of a major Viet Cong bunker system sited on two spur lines in the vicinity of Hill 65.[23]

Hill 82, 8 November 1965

Brumfield arrived by helicopter on the morning of 8 November, just as A Company was preparing to depart from its night location at 08:00.[24] With contact now seeming unlikely to the Australians, Healy was instructed to move to a rendezvous from which the battalion would be extracted back to Bien Hoa the following day.[19] A Company subsequently set out on a compass bearing which would take them across the northern edge of the Gang Toi plateau. By 10:30 the Australians moved out in single file but had not gone far before a lone Viet Cong scout was observed shadowing them; he was subsequently shot and killed by the rear section.[26] Crossing a creek line the Australians uncovered a company-sized camp of dugouts and trenches, before being fired upon at 15:40 by a single Viet Cong soldier who then fled. A Company halted briefly, and at this time two Viet Cong approached their position, before being killed by 1 Platoon.[27]

The Australians continued in single file towards the top of the plateau, with 1 Platoon—under Sergeant Gordon Peterson—leading, followed by 2 and then 3 Platoon. The going was slow in the dense jungle and visibility was limited. By 16:30 the lead section was nearing the top of the hill having gone just 250 metres (270 yd), while the last platoon—3 Platoon—was still leaving the harbour. Suddenly, 1 Platoon was hit by heavy small arms fire from at least three Viet Cong machine-guns in well-sited bunkers, supported by rifles and grenades. The fire engulfed the lead section and platoon headquarters, causing five casualties in the opening minute. Pinned down, the Australians went to ground and began returning fire, allowing all except one of the wounded to crawl to safety. Private Richard Parker, who had fallen directly in front of the bunker system, was unable to be recovered. Failing to respond to the shouts of his comrades, Parker was exposed to further hits, although was probably already dead. To support the beleaguered platoon, Healy subsequently ordered the support section from company headquarters to move forward to provide covering fire, while 3 Platoon moved up on the left flank.[28] However, due to the dispersed patrolling plan adopted, the remaining companies were unable to provide any assistance.[29]

Still at the bottom of the hill, 3 Platoon—under Second Lieutenant Clive Williams—had just shot and killed two Viet Cong moving along the creek line. Reaching the top of the hill to the left of company headquarters, Williams turned to the right towards the Viet Cong positions. Moving into extended line on a 120 metres (130 yd) front the Australians had advanced just 50 metres (55 yd) before the left flank was engaged by a number of machine-guns from another sector of the Viet Cong position.[28] In danger of being outflanked, 3 Platoon continued to advance regardless, using fire and movement. Just 15 metres (16 yd) from the bunkers Private Peter Gillson, the machine-gunner in the forward section, was shot as he tried to move around the twisted roots of a tall tree.[28] As he fell two Viet Cong rushed forward to take the M60 machine-gun; however, Gillson was still conscious and they were killed at point blank range before he collapsed. Williams radioed Healy of the increasing danger while his platoon sergeant—Sergeant Colin Fawcett—had crawled forward under heavy fire to Gillson, whose body was wedged in the buttress of a large tree. Unable to find a pulse, Fawcett attempted to extract Gillson, but was unable to do so due to heavy fire. Two other attempts to recover the body were also beaten back, and although unsuccessful, Fawcett was later awarded the Military Medal for his actions.[30]

Taking heavy fire from both the front and flanks, Williams had little choice but to withdraw. With the Viet Cong moving rapidly to encircle them, and unable to move forward, the Australians had to fight using small arms fire and grenades to extract themselves back to company headquarters without further casualties.[31] However, by this time the artillery was beginning to have an impact as A Company's forward observer, Captain Bruce Murphy, a New Zealander, directed the fires. The Australians had unavoidably been placed in the worst possible position to their supporting artillery, with 105 Battery firing on a line directly towards them from their gun-line 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) on the other side of the Gang Toi plateau. Consequently, Murphy was unable to observe the fall of shot, and had to walk the rounds onto target by sound. A slight miscalculation could have sent a round over the hill into the Australian positions, regardless, and despite persistent rifle and machine-gun fire, Murphy calmly directed the artillery throughout the battle. For his skill and bravery he was later awarded the Military Cross.[31]

By 18:30, more than two hours since the fighting began, darkness was approaching. The battalion would be unable to concentrate against the Viet Cong position until the following day, and Healy subsequently made the decision to withdraw.[31] With the artillery falling as close as possible, the weight of the indirect fires provided the Australians with a degree of protection and an opportunity to extricate themselves. Lieutenant Ian Guild's 2 Platoon was subsequently moved into position to cover the withdrawal, and carrying their wounded the Australians successfully broke contact without suffering further losses.[32] A Company initially moved to a landing zone 120 metres (130 yd) below the ridgeline which had been cleared to allow the casualties to be evacuated, yet there were no helicopters available. As a result, the Australians had to look after their casualties until the following morning, and they proceeded further north to a night harbour as the area was pounded by artillery, aerial bombing and helicopter gunships.[31]

Healy assessed that his company had encountered a force of at least company-size. Later it became apparent that they had indeed contacted Company 238 which was tasked with protecting the U1 headquarters and to carry out operations in the Bien Hoa region.[31] Throughout the day Viet Cong reconnaissance parties, perhaps including those that had been contacted intermittently, had observed the approaching Australian force on a line leading directly to the U1 headquarters. During the fighting the Viet Cong company commander—Nguyễn Văn Bảo—had split his force into two, allocating one platoon to fight the advancing Australians, and the other two to protect the headquarters. Following the Australian withdrawal Văn Bảo had also withdrawn, pre-empting the ensuing barrage, yet the U1 base remained in communist hands.[18]

Fighting across the Song Dong Nai

Meanwhile, across the river in the American AO the 1/503rd had uncovered a large Viet Cong bunker system and became involved in fierce fighting that had included desperate hand-to-hand combat, with both sides resorting to using bayonets. Throughout the morning the Australians had heard the increasing crescendo of firing as the battle raged; however, as neither they nor the 2/503rd had been called on to reinforce the 1/503rd they had pressed on.[27] The American paratroopers had engaged a well-equipped Viet Cong Main Force regiment, complete with khaki uniforms, steel helmets and Soviet automatic weaponry and small arms. The fighting across the Song Dong Nai continued into the afternoon, before subsiding into sporadic sniper and small arms fire in the later afternoon and early evening.[18] During the fighting, Specialist Lawrence Joel—a medic—distinguished himself tending to his wounded comrades while under heavy fire. He was subsequently awarded the Medal of Honor.[33]

Brumfield demanded the right to return to Hill 82 in order to destroy the bunker system and to recover the bodies of Parker and Gillson, and he and Major John Essex-Clark—the operations officer—began planning a battalion attack.[34] However, with American casualties rising and all available helicopters required for casualty evacuation, the planned operation was cancelled.[17] The thick jungle canopy compounded the issue, and Williamson decided to stage the casualties through an area secured by the Australians at LZ Princess.[29] Operation Hump concluded on 9 November, with the 1/503rd and 1 RAR being extracted by helicopter and returning to Bien Hoa in the late afternoon.[18] Following 1 RAR's return to Bien Hoa, Brumfield continued to petition for permission to conduct the operation.[35] A battalion attack was subsequently planned for 14 November, but Williamson later deferred it dependent on the availability of air and helicopter support, and the start date of the upcoming Operation New Life. Ultimately it was never conducted.[36]

Aftermath

Casualties

The Battle of Gang Toi was the first set-piece action between Australian and Viet Cong forces in the Vietnam War.[37] Australian casualties included two missing (presumed killed) and six wounded, and despite the efforts of their comrades, the bodies of the Australian dead were unable to be recovered.[25] Against these losses the Viet Cong had suffered at least six killed, one wounded and five captured.[38] Confronted by an equal sized force, dug-in in well-prepared defences, the Australians had performed creditably enough even if they had been forced to withdraw, leaving the battlefield to the Viet Cong. Despite inflicting heavier casualties on the communists than they had suffered themselves, many of the Australians were depressed at having left two soldiers behind, and they longed for the opportunity to return to Gang Toi.[18] In 2007, more than 40 years after the fighting, an Australian Vietnam veteran—Jim Bourke, MG—and a team of volunteers successfully located the remains of both Parker and Gillson. They had been hastily buried together in a weapon pit the day after the battle by Viet Cong soldiers, and with the assistance of the Australian and Vietnamese governments they were subsequently returned to Australia for burial.[39]

Assessment

Although A Company, 1 RAR had been mauled, the experience of the Australians at Gang Toi was relatively minor when compared to that of the Americans. During fierce fighting the 1/503rd had suffered 49 killed and 83 wounded, while more than 400 Viet Cong were believed killed.[37] American claims were later raised to over 700 killed when captured documents revealed the losses caused by artillery and air strikes.[35] Yet it was questionable as to whether such battles of attrition would be viable, while equally the American battalion had taken casualties far beyond what would have been politically acceptable for 1 RAR.[36] Indeed, their losses had been significant, and although claimed as a victory, the Americans had failed to secure the area even if the Viet Cong had temporarily surrendered control of the battlefield. Ultimately, the communists continued to use War Zone D as a major base area for the rest of the war.[40]

Brumfield considered Operation Hump to be the least successful operation in which the Australian battalion had participated, and he criticised it as being badly conceived from the start, and mounted with too little intelligence or prior reconnaissance. Indeed, from the initial landing zone being occupied by the Viet Cong, failures in the passage of information, the heavy losses suffered by the 1/503rd and the subsequent difficulties with casualty evacuation, the operation had not run smoothly.[36] The Australians were vengeful for their losses and wanted to return to collect their dead; however, with 1 RAR absorbed into other operations the planned battalion attack on Hill 82 never occurred. Regardless, further operations followed in the months afterwards, with 1 RAR subsequently employed on Operation New Life in November and December, and later Operation Crimp in the Ho Bo Woods in January 1966.[41] Operation Hump was Brumfield's last, with an old football injury forcing his evacuation to Australia in mid-November. He was subsequently replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Alex Preece.[42]

Subsequent operations

At the strategic level the ARVN and the South Vietnamese government had both rallied after appearing on the verge of collapse and the communist threat against Saigon had subsided, yet additional troop increases were required if Westmoreland was to adopt a more offensive strategy, with US troop levels planned to rise from 210,000 in January 1966 to 327,000 by December 1966.[43] The Australian government increased its own commitment to the ground war in March 1966, announcing the deployment of a two battalion brigade—the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF)—with armour, aviation, engineer and artillery support; in total 4,500 men. Additional Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) force elements would also be deployed and with all three services total Australian strength in Vietnam was planned to increase to 6,300 personnel.[44] 1 RAR was subsequently replaced by 1 ATF which was allocated its own area of operations in Phuoc Tuy Province, thereby allowing the Australians to pursue operations more independently using their own counter-insurgency tactics and techniques. The task force arrived between April and June 1966, constructing a base at Nui Dat, while logistic arrangements were provided by the 1st Australian Logistic Support Group which was established at the port of Vung Tau.[45]

Notes

- McNeill 1993, p. 54.

- McNeill 1993, pp. 53–67.

- McNeill 1993, pp. 63–67.

- McNeill 1993, p. 67.

- Mangold & Penycate 1985, pp. 43–44.

- McNeill 1993, p. 66.

- McNeill 1993, p. 95.

- Dennis et al 2008, p. 555.

- McAulay 2005, p. 4.

- McNeill 1993, p. xxv.

- Faley 1999, pp. 34–36.

- McNeill 1993, p. 65.

- Kuring 2004, pp. 321–322.

- McNeill 1993, pp. 85–109.

- Breen 1988, p. 103.

- Breen 1988, p. 110.

- Breen 1988, p. 109.

- McNeill 1993, p. 147.

- Coulthard-Clark 2001, p. 278.

- McNeill 1993, p. 141.

- McNeill 1993, pp. 141–142.

- Breen 1988, p. 111.

- Breen 1988, p. 113.

- McNeill 1993, p. 142.

- Horner 2008, p. 175.

- McNeill 1993, pp. 142–144.

- McNeill 1993, p. 144.

- McNeill 1993, p. 145.

- Breen 1988, p. 121.

- Breen 1988, p. 119.

- McNeill 1993, p. 146.

- Breen 1988, p. 120.

- "Lawrence Joel, Medal of Honor recipient". Vietnam War (A-L). United States Army Center of Military History. 8 June 2009. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- Breen 1988, p. 126.

- Breen 1988, p. 127.

- McNeill 1993, p. 149.

- Coulthard-Clark 2001, p. 279.

- McNeill 1993, p. 441.

- Ham 2007, p. 693.

- Ham 2007, p. 150.

- McNeill 1993, pp. 441–442.

- McNeill 1993, p. 150.

- McNeill 1993, p. 171.

- Horner 2008, p. 177.

- Dennis et al 2008, p. 556.

References

- Breen, Bob (1988). First to Fight: Australian Diggers, NZ Kiwis and US Paratroopers in Vietnam, 1965–66. Nashville, Tennessee: The Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-126-1.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (2001). The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (Second ed.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-634-7.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin; Bou, Jean (2008). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551784-2.

- Faley, Thomas (1999). "Operation Marauder: Allied Offensive in the Mekong Delta". Vietnam. Leesburg, Virginia: Cowels History Group. 11 (5): 34–40. ISSN 1046-2902.

- Ham, Paul (2007). Vietnam: The Australian War. Sydney, New South Wales: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-7322-8237-0.

- Horner, David, ed. (2008). Duty First: A History of the Royal Australian Regiment (Second ed.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-374-5.

- Kuring, Ian (2004). Redcoats to Cams: A History of Australian Infantry 1788–2001. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military Historical Publications. ISBN 1-87643-999-8.

- Mangold, Tom; Penycate, John (1985). The Tunnels of Cu Chi. London, United Kingdom: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-29191-2. OCLC 13825759.

- McAulay, Lex (2005). Blue Lanyard, Red Banner: The Capture of a Vietcong Headquarters by 1st Battalion The Royal Australian Regiment Operation CRIMP 8–14 January 1966. Maryborough, Queensland: Banner Books. ISBN 1-875593-28-4.

- McNeill, Ian (1993). To Long Tan: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1950–1966. The Official History of Australia's Involvement in Southeast Asian Conflicts 1948–1975. Vol. Two. St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-282-9.