Battle of Fort Donelson

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11–16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The Union capture of the Confederate fort near the Tennessee–Kentucky border opened the Cumberland River, an important avenue for the invasion of the South. The Union's success also elevated Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant from an obscure and largely unproven leader to the rank of major general, and earned him the nickname of "Unconditional Surrender" Grant.

| Battle of Fort Donelson | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

_(14590258419).jpg.webp) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

24,531[2] | 16,171[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,691 total |

13,846 total (327 killed 1,127 wounded 12,392 captured/missing)[3] | ||||||

Following his capture of Fort Henry on February 6, Grant moved his army (later to become the Union's Army of the Tennessee[4]) 12 miles (19 km) overland to Fort Donelson, from February 11 to 13, and conducted several small probing attacks. On February 14, Union gunboats under Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote attempted to reduce the fort with gunfire, but were forced to withdraw after sustaining heavy damage from the fort's water batteries.

On February 15, with the fort surrounded, the Confederates, commanded by Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, launched a surprise attack, led by his second-in-command, Brig. Gen. Gideon Johnson Pillow, against the right flank of Grant's army. The intention was to open an escape route for retreat to Nashville, Tennessee. Grant was away from the battlefield at the start of the attack, but arrived to rally his men and counterattack. Pillow's attack succeeded in opening the route, but Floyd lost his nerve and ordered his men back to the fort. The following morning, Floyd and Pillow escaped with a small detachment of troops, relinquishing command to Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, who accepted Grant's demand of unconditional surrender later that evening. The battle resulted in virtually all of Kentucky as well as much of Tennessee, including Nashville, falling under Union control.

Background

Military situation

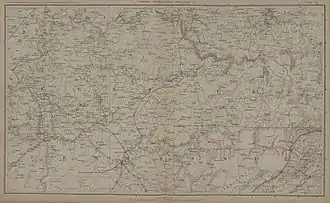

The battle of Fort Donelson, which began on February 12, took place shortly after the surrender of Fort Henry, Tennessee, on February 6, 1862. Fort Henry had been a key position in the center of a line defending Tennessee, and the capture of the fort now opened the Tennessee River to Union troop and supply movements. About 2,500 of Fort Henry's Confederate defenders escaped before its surrender by marching the 12 miles (19 km) east to Fort Donelson.[5] In the days following the surrender at Fort Henry, Union troops cut the railroad lines south of the fort, restricting the Confederates' lateral mobility to move reinforcements into the area to defend against the larger Union forces.[6]

With the surrender of Fort Henry, the Confederates faced some difficult choices. Grant's army now divided Confederate Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston's two main forces: P.G.T. Beauregard at Columbus, Kentucky, with 12,000 men, and William J. Hardee at Bowling Green, Kentucky, with 22,000 men. Fort Donelson had only about 5,000 men. Union forces might attack Columbus; they might attack Fort Donelson and thereby threaten Nashville, Tennessee; or Grant and Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, who was quartered in Louisville with 45,000 men, might attack Johnston head-on, with Grant following behind Buell. Johnston was apprehensive about the ease with which Union gunboats defeated Fort Henry (not comprehending that the rising waters of the Tennessee River played a crucial role by inundating the fort). He was more concerned about the threat from Buell than he was from Grant, and suspected the river operations might simply be a diversion.[6]

Johnston decided upon a course of action that forfeited the initiative across most of his defensive line, tacitly admitting that the Confederate defensive strategy for Tennessee was a sham. On February 7, at a council of war held in the Covington Hotel at Bowling Green, he decided to abandon western Kentucky by withdrawing Beauregard from Columbus, evacuating Bowling Green, and moving his forces south of the Cumberland River at Nashville. Despite his misgivings about its defensibility, Johnston agreed to Beauregard's advice that he should reinforce Fort Donelson with another 12,000 men, knowing that a defeat there would mean the inevitable loss of Middle Tennessee and the vital manufacturing and arsenal city of Nashville.[7]

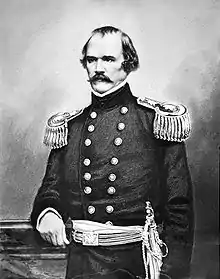

Johnston wanted to give command of Fort Donelson to Beauregard, who had performed ably at Bull Run, but the latter declined because of a throat ailment. Instead, the responsibility went to Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, who had just arrived following an unsuccessful assignment under Robert E. Lee in western Virginia. Floyd was a wanted man in the North for alleged graft and secessionist activities when he was Secretary of War in the James Buchanan administration. Floyd's background was political, not military, but he was nevertheless the senior brigadier general on the Cumberland River.[8]

On the Union side, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, Grant's superior as commander of the Department of the Missouri, was also apprehensive. Halleck had authorized Grant to capture Fort Henry, but now he felt that continuing to Fort Donelson was risky. Despite Grant's success to date, Halleck had little confidence in him, considering Grant to be reckless. Halleck attempted to convince his own rival, Don Carlos Buell, to take command of the campaign to get his additional forces engaged. Despite Johnston's high regard for Buell, the Union general was as passive as Grant was aggressive. Grant never suspected his superiors were considering relieving him, but he was well aware that any delay or reversal might be an opportunity for Halleck to lose his nerve and cancel the operation.[9]

On February 6, Grant wired Halleck: "Fort Henry is ours. ... I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry."[10] This self-imposed deadline was overly optimistic due to three factors: miserable road conditions on the twelve-mile march to Donelson, the need for troops to carry supplies away from the rising flood waters (by February 8, Fort Henry was completely submerged),[11] and the damage that had been sustained by Foote's Western Gunboat Flotilla in the artillery duel at Fort Henry. If Grant had been able to move quickly, he might have taken Fort Donelson on February 8. Early in the morning of February 11, Grant held a council of war in which all of his generals supported his plans for an attack on Fort Donelson, with the exception of Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand, who had some reservations. This council in early 1862 was the last one that Grant held for the remainder of the Civil War.[12]

Opposing forces

Union

| Union commanders |

|---|

|

Grant's Union Army of the Tennessee of the District of Cairo consisted of three divisions, commanded by Brig. Gens. McClernand, C.F. Smith, and Lew Wallace. (At the start of the attack on Fort Donelson, Wallace was a brigade commander in reserve at Fort Henry, but was summoned on February 14 and charged with assembling a new division that included reinforcements arriving by steamship, including Charles Cruft's brigade on loan from Buell.) Two regiments of cavalry and eight batteries of artillery supported the infantry divisions. Altogether, the Union forces numbered nearly 25,000 men, although at the start of the battle, only 15,000 were available.[13]

The Western Gunboat Flotilla under Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote consisted of four ironclad gunboats (flagship USS St. Louis, USS Carondelet, USS Louisville, and USS Pittsburg) and three timberclad (wooden) gunboats (USS Conestoga, USS Tyler, and USS Lexington). USS Essex and USS Cincinnati had been damaged at Fort Henry and were being repaired.[14]

Confederate

| Confederate commanders |

|---|

|

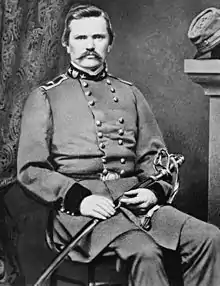

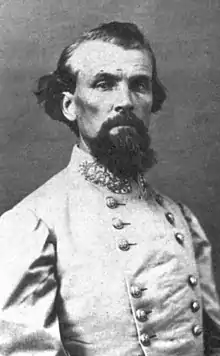

Floyd's Confederate force of approximately 17,089 men consisted of three divisions (Army of Central Kentucky), garrison troops, and attached cavalry. The three divisions were commanded by Floyd (replaced by Colonel Gabriel C. Wharton when Floyd took command of the entire force) and Brig. Gens. Bushrod Johnson and Simon Bolivar Buckner. During the battle, Johnson, the engineering officer who briefly commanded Fort Donelson in late January, was effectively superseded by Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow (Grant's opponent at his first battle at Belmont). Pillow, who arrived at Fort Donelson on February 9, was displaced from overall command of the fort when the more-senior Floyd arrived.[15] The garrison troops were commanded by Col. John W. Head and the cavalry by Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest.[16]

Fort Donelson was named for Brig. Gen. Daniel S. Donelson, who selected its site and began construction in 1861. It was considerably more formidable than Fort Henry. Fort Donelson rose about 100 feet (30 m) on approximately 100 acres of dry ground above the Cumberland River, which allowed for plunging fire against attacking gunboats, an advantage Fort Henry did not enjoy.[17] The river batteries included twelve guns: ten 32-pounder smoothbore cannons, two 9-pounder smoothbore cannons, an 8-inch howitzer, a 6.5-inch rifle (128-pounder), and a 10-inch Columbiad. There were three miles (5 km) of trenches in a semicircle around the fort and the small town of Dover. The outer works were bounded by Hickman Creek to the west, Lick Creek to the east, and the Cumberland River to the north. These trenches, located on a commanding ridge and fronted by a dense abatis of cut trees and limbs stuck into the ground and pointing outward,[17] were backed up by artillery and manned by Buckner and his Bowling Green troops on the right (with his flank anchored on Hickman Creek), and Johnson/Pillow on the left (with his flank near the Cumberland River). Facing the Confederates, from left to right, were Smith, Lew Wallace (who arrived on February 14), and McClernand. McClernand's right flank, which faced Pillow, had insufficient men to reach overflowing Lick Creek, so it was left unanchored. Through the center of the Confederate line ran the marshy Indian Creek, this point defended primarily by artillery overlooking it on each side.[18]

Battle

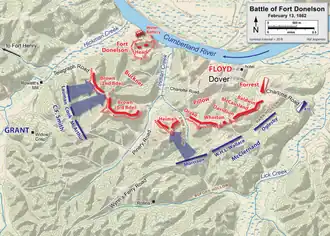

Preliminary movements and attacks (February 12–13)

On February 12, most of the Union troops departed Fort Henry, where they were waiting for the return of Union gunboats and the arrival of additional troops that would increase the Union forces to about 25,000 men.[15] The Union forces proceeded about 5 miles (8 km) on the two main roads leading between the two forts. They were delayed most of the day by a cavalry screen commanded by Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest's troops, sent out by Buckner, spotted a detachment from McClernand's division and opened fire against them. A brief skirmish ensued until orders from Buckner arrived to fall back within the entrenchments. After this withdrawal of Forrest's cavalry, the Union troops moved closer to the Confederate defense line while trying to cover any possible Confederate escape routes. McClernand's division made up the right of Grant's army with C.F. Smith's division forming the left.[19] USS Carondelet was the first gunboat to arrive up the river, and she promptly fired numerous shells into the fort, testing its defenses before retiring. Grant arrived on February 12 and established his headquarters near the left side of the front of the line, at the Widow Crisp's house.[20]

On February 11, Buckner relayed orders to Pillow from Floyd to release Floyd's and Buckner's troops to operate south of the river, near Cumberland City, where they would be able to attack the Union supply lines while keeping a clear path back to Nashville. However, this would leave the Confederate forces at Fort Donelson heavily outnumbered. Gen. Pillow left early on the morning of February 12 to argue these orders with Gen. Floyd himself leaving Buckner in charge of the fort. After hearing sounds of artillery fire, Pillow returned to Fort Donelson to resume command. After the events of the day, Buckner remained at Fort Donelson to command the Confederate right. With the arrival of Grant's army, General Johnston ordered Floyd to take any troops remaining in Clarksville to aid in the defense of Fort Donelson.[21]

On February 13, several small probing attacks were carried out against the Confederate defenses, essentially ignoring orders from Grant that no general engagement be provoked. On the Union left, C. F. Smith sent two of his four brigades (under Cols. Jacob Lauman and John Cook) to test the defenses along his front. The attack suffered light casualties and made no gains, but Smith was able to keep up a harassing fire throughout the night. On the right, McClernand also ordered an unauthorized attack. Two regiments of Col. William R. Morrison's brigade, along with one regiment, the 48th Illinois, from Col. W.H.L. Wallace's brigade, were ordered to seize a battery ("Redan Number 2") that had been plaguing their position. Isham N. Haynie, colonel of the 48th Illinois, was senior in rank to Colonel Morrison. Although rightfully in command of two of the three regiments, Morrison volunteered to turn over command once the attack was under way; however, when the attack began, Morrison was wounded, eliminating any leadership ambiguity. For unknown reasons Haynie never fully took control and the attack was repulsed. Some wounded men caught between the lines burned to death in grass fires ignited by the artillery.[22]

General Grant had Commander Henry Walke bring the Carondelet up the Cumberland River to create a diversion by opening fire on the fort. The Confederates responded with shots from their long-range guns and eventually hit the gunboat. Walke retreated several miles below the fort, but soon returned and continued shelling the water batteries. General McClernand, in the meantime, had been attempting to stretch his men toward the river but ran into difficulties with a Confederate battery of guns. McClernand ultimately decided that he did not have enough men to stretch all the way to the river, so Grant decided to call on more troops. He sent orders to General Wallace, who had been left behind at Fort Henry, to bring his men to Fort Donelson.[23]

With Floyd's arrival to take command of Fort Donelson, Pillow took over leading the Confederate left. Feeling overwhelmed, Floyd left most of the actual command to Pillow and Buckner. At the end of the day, there had been several skirmishes, but the positions of each side were essentially the same. The night progressed with both sides fighting the cold weather.[24]

Although the weather had been mostly rainy up to this point in the campaign, a snow storm arrived the night of February 13, with strong winds that brought temperatures down to 10–12 °F (−12 °C) and deposited 3 inches (8 cm) of snow by morning. Guns and wagons were frozen to the earth. Because of the proximity of the enemy lines and the active sharpshooters, the soldiers could not light campfires for warmth or cooking, and both sides were miserable that night, many having arrived without blankets or overcoats.[25]

_(14782670293).jpg.webp)

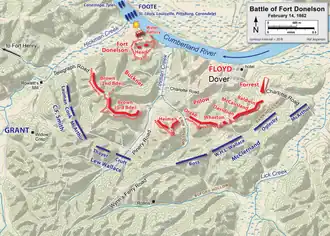

Reinforcements and naval battle (February 14)

At 111:00 a.m. on February 14, Floyd held a council of war in his headquarters at the Dover Hotel. There was general agreement that Fort Donelson was probably untenable. General Pillow was designated to lead a breakout attempt, evacuate the fort, and march to Nashville. Troops were moved behind the lines and the assault readied and they broke through Union lines, but Grant sent them back to Fort Donelson reeling. Pillow, normally quite aggressive in battle, was unnerved and announced that since their movement had been detected, the breakout was sent back.

On February 14, General Lew Wallace's brigade arrived from Fort Henry around noon, and Foote's flotilla arrived on the Cumberland River in mid-afternoon, bringing six gunboats and another 10,000 Union reinforcements on twelve transport ships. Wallace assembled these new troops into a third division of two brigades, under Cols. John M. Thayer and Charles Cruft, and occupied the center of the line facing the Confederate trenches. This provided sufficient troops to extend McClernand's right flank to be anchored on Lick Creek, by moving Col. John McArthur's brigade of Smith's division from the reserve to a position from which they intended to plug the 400 yards (370 m) gap at dawn the next morning.[26]

_(14576157349).jpg.webp)

As soon as Foote arrived, Grant urged him to attack the fort's river batteries. Although Foote was reluctant to proceed before adequate reconnaissance, he moved his gunboats close to the shore by 3:00 p.m. and opened fire, just as he had done at Fort Henry. Confederate gunners waited until the gunboats were within 400 yards (370 m) to return fire. The Confederate artillery pummeled the fleet and the assault was over by 4:30 p.m. Foote was wounded (coincidentally in his foot). The wheelhouse of his flagship, USS St. Louis, was carried away, and she floated helplessly downriver. USS Louisville was also disabled and the Pittsburg began to take on water. The damage to the fleet was significant and it retreated downriver.[27] Of the 500 Confederate shots fired, St. Louis was hit 59 times, Carondelet 54, Louisville 36, and Pittsburg 20 times. Foote had miscalculated the assault. Historian Kendall Gott suggested that it would have been more prudent to stay as far downriver as possible, and use the fleet's longer-range guns to reduce the fort. An alternative might have been to overrun the batteries, probably at night as would be done successfully in the 1863 Vicksburg Campaign. Once the Union fleet was past the fixed river batteries, Fort Donelson would have been defenseless.[28]

Eight Union sailors were killed and 44 were wounded while the Confederates lost none. (Captain Joseph Dixon of the river batteries had been killed the previous day during Carondelet's bombardment.) On land the well-armed Union soldiers surrounded the Confederates, while the Union boats, although damaged, still controlled the river. Grant realized that any success at Fort Donelson would have to be carried by the army without strong naval support, and he wired Halleck that he might have to resort to a siege.[29]

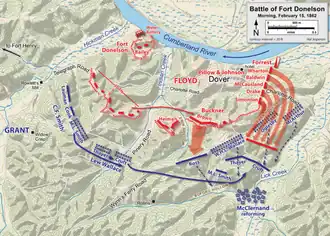

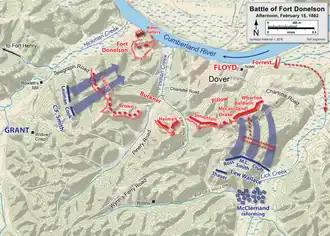

Breakout attempt (February 15)

Despite their unexpected naval success, the Confederate generals were still skeptical about their chances in the fort and held another late-night council of war, where they decided to retry their aborted escape plan. At dawn on February 15, the Confederates launched an assault led by Pillow against McClernand's division on the unprotected right flank of the Union line. The Union troops, unable to sleep in the cold weather, were not caught entirely by surprise, but Grant was. Not expecting a land assault from the Confederates, he was up before dawn and had headed off to visit Flag Officer Foote on his flagship downriver. Grant left orders that none of his generals was to initiate an engagement and no one was designated as second-in-command during his absence.[30]

The Confederate plan was for Pillow to push McClernand away and take control of Wynn's Ferry and Forge Roads, the main routes to Nashville.[17] Buckner was to move his division across Wynn's Ferry Road and act as rear guard for the remainder of the army as it withdrew from Fort Donelson and moved east. A lone regiment from Buckner's division—the 30th Tennessee—was designated to stay in the trenches and prevent a Federal pursuit. The attack started well, and after two hours of heavy fighting, Pillow's men pushed McClernand's line back and opened the escape route. It was in this attack that Union troops in the West first heard the famous, unnerving rebel yell.[31]

The attack was initially successful because of the inexperience and poor positioning of McClernand's troops and a flanking attack from the Confederate cavalry under Forrest. The Union brigades of Cols. Richard Oglesby and John McArthur were hit hardest; they withdrew in a generally orderly manner to the rear for regrouping and resupply. Around 8:00 a.m. McClernand sent a message requesting assistance from Lew Wallace, but Wallace had no orders from Grant, who was still absent, to respond to an attack on a fellow officer and declined the initial request. Wallace, who was hesitant to disobey orders, sent an aide to Grant's headquarters for further instructions.[32] In the meantime, McClernand's ammunition was running out, but his withdrawal was not yet a rout. (The army of former quartermaster Ulysses S. Grant had not yet learned to organize reserve ammunition and supplies near the frontline brigades.) A second messenger arrived at Wallace's camp in tears, crying, "Our right flank is turned! ... The whole army is in danger!"[33] This time Wallace sent a brigade, under Col. Charles Cruft, to aid McClernand. Cruft's brigade was sent in to replace Oglesby's and McArthur's brigades, but when they realized they had run into Pillow's Confederates and were being flanked, they too began to fall back.[34]

Not everything was going well with the Confederate advance. By 9:30 a.m., as the lead Union brigades were falling back, Nathan Bedford Forrest urged Bushrod Johnson to launch an all-out attack on the disorganized troops. Johnson was too cautious to approve of a general assault, but he did agree to keep the infantry moving slowly forward. Two hours into the battle, Gen. Pillow realized that Buckner's wing was not attacking alongside his. After a confrontation between the two generals, Buckner's troops moved out and, combined with the right flank of Pillow's wing, hit W. H. L. Wallace's brigade. The Confederates took control of Forge Road and a key section of Wynn's Ferry Road, opening a route to Nashville,[35] but Buckner's delay provided time for Lew Wallace's men to reinforce McClernand's retreating forces before they were completely routed. Despite Grant's earlier orders, Wallace's units moved to the right with Thayer's brigade, giving McClernand's men time to regroup and gather ammunition from Wallace's supplies. The 68th Ohio was left behind to protect the rear.[36]

The Confederate offensive ended around 12:30 p.m., when Wallace's and Thayer's Union troops formed a defensive line on a ridge astride Wynn's Ferry Road. The Confederates assaulted them three times, but were unsuccessful and withdrew to a ridge 0.5 miles (0.80 km) away. Nevertheless, they had had a good morning. The Confederates had pushed the Union defenders back one to two miles (2–3 km) and had opened their escape route.[37]

Grant, who was apparently unaware of the battle, was notified by an aide and returned to his troops in the early afternoon. Grant first visited C. F. Smith on the Union left, where Grant ordered the 8th Missouri and the 11th Indiana to the Union right,[17] then rode 7 miles (11 km) over icy roads to find McClernand and Wallace. Grant was dismayed at the confusion and a lack of organized leadership. McClernand grumbled "This army wants a head." Grant replied, "It seems so. Gentlemen, the position on the right must be retaken."[38]

True to his nature, Grant did not panic at the Confederate assault. As Grant rode back from the river, he heard the sounds of guns and sent word to Foote to begin a demonstration of naval gunfire, assuming that his troops would be demoralized and could use the encouragement. Grant observed that some of the Confederates (Buckner's) were fighting with knapsacks filled with three days of rations, which implied to him that they were attempting to escape, not pressing for a combat victory. He told an aide, "The one who attacks first now will be victorious. The enemy will have to be in a hurry if he gets ahead of me."[39]

Despite the successful morning attack, access to an open escape route, and to the amazement of Floyd and Buckner, Pillow ordered his men back to their trenches by 1:30 p.m. Buckner confronted Pillow, and Floyd intended to countermand the order, but Pillow argued that his men needed to regroup and resupply before evacuating the fort. Pillow won the argument. Floyd also believed that C. F. Smith's division was being heavily reinforced, so the entire Confederate force was ordered back inside the lines of Fort Donelson, giving up the ground they gained earlier that day.[40]

Grant moved quickly to exploit the opening and told Smith, "All has failed on our right—you must take Fort Donelson." Smith replied, "I will do it." Smith formed his two remaining brigades to make an attack. Lauman's brigade would be the main attack, spearheaded by Col. James Tuttle's 2nd Iowa Infantry. Cook's brigade would be in support to the right and rear and act as a feint to draw fire away from Lauman's brigade. Smith's two-brigade attack quickly seized the outer line of entrenchments on the Confederate right from the 30th Tennessee, commanded by Col. John W. Head, who had been left behind from Buckner's division. Despite two hours of repeated counterattacks, the Confederates could not repel Smith from the captured earthworks. The Union was now poised to seize Fort Donelson and its river batteries when light returned the next morning.[41] In the meantime, on the Union right, Lew Wallace formed an attacking column with three brigades—one from his own division, one from McClernand's, and one from Smith's—to try to regain control of ground lost in the battle that morning. Wallace's old brigade of Zouaves (11th Indiana and 8th Missouri), now commanded by Col. Morgan L. Smith, and others from McClernand's and Wallace's divisions were chosen to lead the attack. The brigades of Cruft (Wallace's Division) and Leonard F. Ross (McClernand's Division) were placed in support on the flanks. Wallace ordered the attack forward. Smith, the 8th Missouri, and the 11th Indiana advanced a short distance up the hill using Zouave tactics, where the men repeatedly rushed and then fell to the ground in a prone position.[42] By 5:30 p.m. Wallace's troops had succeeded in retaking the ground lost that morning,[43] and by nightfall, the Confederate troops had been driven back to their original positions. Grant began plans to resume his assault in the morning, although neglecting to close the escape route that Pillow had opened.[44]

John A. Logan was gravely injured on February 15. Soon after the victory at Donelson, he was promoted to brigadier general in the volunteers.

Surrender (February 16)

Nearly 1,000 soldiers on both sides had been killed, with about 3,000 wounded still on the field; some froze to death in the snowstorm, many Union soldiers having thrown away their blankets and coats.[45]

Inexplicably, generals Floyd and Pillow were upbeat about the day's performance and wired General Johnston at Nashville that they had won a great victory. General Simon Bolivar Buckner, however, argued that they were in a desperate position that was getting worse with the arrival of Union reinforcements. At their final council of war in the Dover Hotel at 1:30 a.m. on February 16, Buckner stated that if C.F. Smith attacked again, he could only hold for thirty minutes, and he estimated that the cost of defending the fort would be as high as a seventy-five percent casualty rate. Buckner's position finally carried the meeting. Any large-scale escape would be difficult. Most of the river transports were currently transporting wounded men to Nashville and would not return in time to evacuate the command.[46]

Floyd, who believed if he was captured, he would be indicted for corruption during his service as Secretary of War in President James Buchanan's cabinet before the war, promptly turned over his command to Pillow, who also feared Northern reprisals. In turn, Pillow passed the command to Buckner, who agreed to remain behind and surrender the army. During the night, Pillow escaped by small boat across the Cumberland. Floyd left the next morning on the only steamer available, taking his two regiments of Virginia infantry. Disgusted at the show of cowardice, a furious Nathan Bedford Forrest announced, "I did not come here to surrender my command." He stormed out of the meeting and led about seven hundred of his cavalrymen on their escape from the fort. Forrest's horsemen rode toward Nashville through the shallow, icy waters of Lick Creek, encountering no enemy and confirming that many more could have escaped by the same route, if Buckner had not posted guards to prevent any such attempts.[47]

On the morning of February 16, Buckner sent a note to Grant requesting a truce and asking for terms of surrender. The note first reached General Smith, who exclaimed, "No terms to the damned Rebels!" When the note reached Grant, Smith urged him to offer no terms. Buckner had hoped that Grant would offer generous terms because of their earlier friendship. (In 1854 Grant was removed from command at a U.S. Army post in California, allegedly because of alcoholism. Buckner, a fellow U.S. Army officer at that time, loaned Grant money to return home to Illinois after Grant had been forced to resign his commission.) To Buckner's dismay, Grant showed no mercy towards men rebelling against the federal government. Grant's brusque reply became one of the most famous quotes of the war, earning him the nickname of "Unconditional Surrender":[48]

_(14576149958).jpg.webp)

Sir: Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.

I propose to move immediately upon your works.

- I am Sir: very respectfully

- Yours

- U.S. Grant

- Brig. Gen.[49]

Grant was not bluffing. Smith was now in a good position to move on the fort, having captured the outer lines of its fortifications, and was under orders to launch an attack with the support of other divisions the following day. Grant believed his position allowed him to forego a planned siege and successfully storm the fort.[50] Buckner responded to Grant's demand:

SIR:—The distribution of the forces under my command, incident to an unexpected change of commanders, and the overwhelming force under your command, compel me, notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms yesterday, to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms which you propose.[51]

Grant, who was courteous to Buckner following the surrender, offered to loan him money to see him through his impending imprisonment, but Buckner declined. The surrender was a personal humiliation for Buckner and a strategic defeat for the Confederacy, which lost more than 12,000 men, 48 artillery pieces, much of their equipment, and control of the Cumberland River, which led to the evacuation of Nashville.[52] This was the first of three Confederate armies that Grant would capture during the war. (The second was John C. Pemberton's at the Siege of Vicksburg and the third Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox). Buckner also turned over considerable military equipment and provisions, which Grant's troops badly needed. More than 7,000 Confederate prisoners of war were eventually transported from Fort Donelson to Camp Douglas in Chicago, Camp Morton in Indianapolis,[53] and other prison camps elsewhere in the North. Buckner was held as a prisoner at Fort Warren in Boston until he was exchanged in August 1862.[54]

Aftermath

The casualties at Fort Donelson were heavy, primarily because of the large Confederate surrender. Union losses were 2,691 (507 killed, 1,976 wounded, 208 captured/missing), Confederate 13,846 (327 killed, 1,127 wounded, 12,392 captured/missing).[3]

Cannons were fired and church bells rung throughout the North at the news. The Chicago Tribune wrote that "Chicago reeled mad with joy." The capture of Forts Henry and Donelson were the first significant Union victories in the war and opened two great rivers to invasion in the heartland of the South. Grant was promoted to major general of volunteers, second in seniority only to Henry W. Halleck in the West. After newspapers reported that Grant had won the battle with a cigar clamped in his teeth, he was inundated with cigars sent from his many admirers. Before that he'd been only a light smoker, but after finding that he couldn't give them all away, took to smoking them, which probably contributed to his later death from throat cancer. Grant had written in his memoirs that if all Union troops in the west were unified under a single commander to capitalize on the victory at Fort Donelson, the fighting in the western theaters of the civil war would've been closed quickly.[55] Close to a third of all of Albert Sidney Johnston's forces were now prisoners. Grant had captured more soldiers than all previous American generals combined, and Johnston was thereby deprived of more than twelve thousand soldiers who might have provided a decisive advantage at the impending Battle of Shiloh in less than two months time. The rest of Johnston's forces were 200 miles (320 km) apart, between Nashville and Columbus, with Grant's army between them. Grant's forces also controlled nearby rivers and railroads. General Buell's army threatened Nashville, while John Pope's troops threatened Columbus. Johnston evacuated Nashville on February 23, surrendering this important industrial center to the Union and making it the first Confederate state capital to fall. Columbus was evacuated on March 2. Most of Tennessee fell under Union control, as did all of Kentucky, although both were subject to invasion and periodic Confederate raiding.[56]

Battlefield preservation

The site of the battle has been preserved by the National Park Service as Fort Donelson National Battlefield. Through November 2021, the American Battlefield Trust and its partners in battlefield land preservation have acquired and preserved 369 acres (1.49 km2) of the battlefield, most of which has been conveyed to the park service and incorporated into the park.[57]

See also

- Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

- Ulysses S. Grant and the American Civil War

- Shiloh National Military Park

- Battle of Fort Henry

- Battle of Island Number Ten

- Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1862

- List of costliest American Civil War land battles

- Armies in the American Civil War

- Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps

- Turning point of the American Civil War

- Mary Ann Brown Newcomb, nursed Union Army soldiers

Notes

- NPS

- Gott, pp. 284–88. The Union strength includes both the Army and Navy units.

- Gott, pp. 284–85, 288.

- Woodworth, p. 10.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 12–13; Esposito, text for map 26.

- Esposito, map 25; Gott, pp. 65, 122; Nevin, p. 79.

- Nevin, p. 81; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 18; Gott, pp. 121–23.

- Gott, p. 67; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 18, 23.

- Woodworth, p. 84; Gott, pp. 118–19.

- McPherson, p. 397.

- Gott, p. 105.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 20; Gott, p. 136.

- Esposito, map 26; Gott, pp. 138, 282–85; Nevin, p. 81; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 21.

- Gott, pp. 117, 180.

- Stephens, p. 47.

- Eicher, p. 173; Gott, pp. 286–88.

- Stephens, p. 50.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 5–6; Kennedy, p. 45; Foote, p. 194; Gott, pp. 16–17, 173, 180.

- Knight, Fort Donelson, pp. 98–102; Knight, Nothing But God, p. 2.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 21; Gott, pp. 144–47; Nevin, p. 81.

- Knight, Fort Donelson, pp. 97–101.

- Gott, pp. 157–64; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 23–25; Nevin, p. 82; Woodworth, pp. 86–88.

- Cooling, Fort Donelson's Legacy, p. 2; Hamilton, p. 100; Knight, Fort Donelson, pp. 104–105.

- Knight, p. Fort Donelson, pp. 104, 107.

- Woodworth, pp. 89–90; Gott, pp. 165–66; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 25–26; Eicher, p. 173.

- Nevin, p. 82; Gott, pp. 174–75; Woodworth, p. 91.

- Stephens, p. 50, and Nevin, p. 83–84.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 26–27; Nevin, pp. 83–84; Gott, pp. 177–82.

- Gott, pp. 182–83.

- Nevin, pp. 84–86; Gott, p. 192; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 28–29; Woodworth, p. 94.

- Gott, pp. 191, 201; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 29; Eicher, p. 175.

- Stephens, p. 50–51, and Nevin, p. 86–87.

- Nevin, p. 87.

- Nevin, pp. 86–87; Gott, pp. 194–203; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 29; Woodworth, p. 96.

- Stephens, p. 52.

- Stephens, p. 53–54.

- Gott, pp. 204–17; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 31.

- Nevin, p. 90.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 31–32; Nevin, pp. 87–90; Gott, pp. 222–24; Eicher, p. 176.

- Eicher, p. 176; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 31; Nevin, p. 90; Gott, pp. 220–21.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 32–33; Nevin, p. 90; Gott, pp. 226–31; Woodworth, pp. 108–11.

- Stephens, p. 56.

- Stephens, p. 57.

- Gott, pp. 231–35; Woodworth, pp. 111–13; Eicher, p. 178; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, pp. 33–34.

- Eicher, p. 178; Nevin, p. 34.

- Nevin, p. 93; Gott, pp. 237–40; Woodworth, p. 115; Eicher, p. 178; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 35.

- Stephens, p. 58; Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 37; Gott, pp. 240–41, 252–53; Woodworth, p. 116; Nevin, pp. 93–94.

- Nevin, p. 94; Gott, pp. 254–57.

- Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 36.

- Esposito, map 29.

- Gott, p. 257

- Gott, pp. 262–67

- Hattie Lou Winslow & Joseph R. H. Moore (1995). Camp Morton, 1861–1865: Indianapolis Prison Camp. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 69. ISBN 0-87195-114-2.

- No formal records were taken of the Confederates who surrendered and estimates vary. Gott, pp. 257–63, 265, cites 12,392. Esposito, map 29: 11,500. McPherson, p. 402: 12,000 to 13,000. Cooling, Campaign for Fort Donelson, p. 38: 12,000 to 15,000. Nevin, p. 97: 12,000 to 15,000. Kennedy, p. 47: 15,000. Woodworth, p. 119: 15,000. Buckner was a Union prisoner of war at Fort Warren in Boston until August 15, 1862, when he was exchanged for Brig. Gen. George A. McCall; see Buckner biography.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Memoirs. pp. 222–223.

- Nevin, p. 96; Gott, pp. 266–67; Esposito, maps 30–31.

- American Battlefield Trust "Saved Land" webpage. November 30, 2021.

Bibliography

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. The Campaign for Fort Donelson. National Park Service Civil War series. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 1999. ISBN 1-888213-50-7.

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. Fort Donelson's Legacy: War and Society in Kentucky and Tennessee, 1862–1863. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997. ISBN 0-87049-949-1.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 1, Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- Hamilton, James J. "The Battle of Fort Donelson." The Journal of Southern History 35.1 (1969): 99–100. JSTOR. Web. 21 Mar. 2015.

- Gott, Kendall D. Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Knight, James R. The Battle of Fort Donelson: No Terms but Unconditional Surrender. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-60949-129-1.

- Knight, James R. "Nothing but God Almighty Can Save That Fort." Civil War Trust website, accessed March 21, 2015.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983. ISBN 0-8094-4716-9.

- Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity, 1822–1865. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000. ISBN 0-395-65994-9.

- Stephens, Gail. The Shadow of Shiloh: Major General Lew Wallace in the Civil War. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-87195-287-5.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 0-375-41218-2.

- National Park Service battle description

Memoirs and primary sources

- Robert Underwood Johnson, Clarence Clough Buell, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: The Opening Battles, Volume 1 (Pdf), New York: The Century Co., 1887.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

- Bush, Bryan S. Lloyd Tilghman: Confederate General in the Western Theatre. Morley, MO: Acclaim Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-9773198-4-8.

- Catton, Bruce. Grant Moves South. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1960. ISBN 0-316-13207-1.

- Cummings, Charles Martin. Yankee Quaker, Confederate General: The Curious Career of Bushrod Rust Johnson. Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-8386-7706-1.

- Engle, Stephen Douglas. Struggle for the Heartland: The Campaigns from Fort Henry to Corinth. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8032-1818-4.

- Hamilton, James J. The Battle of Fort Donelson. South Brunswick, NJ: T. Yoseloff, 1968. OCLC 2579774.

- Huffstodt, James. Hard Dying Men: The Story of General W. H. L. Wallace, General Thomas E. G. Ransom, and the "Old Eleventh" Illinois Infantry in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Bowie, MD: Heritage Press. ISBN 1-55613-510-6.

- Hurst, Jack. Men of Fire: Grant, Forrest, and the Campaign that Decided the Civil War. New York: Basic Books, 2007. ISBN 0-465-03184-6.

- McPherson, James M., ed. The Atlas of the Civil War. New York: Macmillan, 1994. ISBN 0-02-579050-1.

- Perry, James M. Touched with Fire: Five Presidents and the Civil War Battles That Made Them. New York: PublicAffairs, 2003. ISBN 1-58648-114-2.

- Slagle, Jay. Ironclad Captain: Seth Ledyard Phelps & the U.S. Navy, 1841–1864. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-87338-550-3.

- Smith, Timothy B. Grant Invades Tennessee: The 1862 Battles for Forts Henry and Donelson. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7006-2313-6.

- Wallace, Isabel, and William Hervy Lamme Wallace. Life and Letters of General W.H.L. Wallace. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8093-2347-8.

External links

- Battle of Fort Donelson: Battle Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Animated history of the Battles of Forts Henry and Donelson

- Newspaper coverage of the Battle of Fort Donelson Archived June 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- paintings of Fort Donelson Battlefield Archived March 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Battles for Forts Henry, Heiman & Donelson

- BATTLE OF FORT DONELSON

- American Civil War: Battle of Fort Donelson Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- The Battle of Fort Donelson, Tennessee

- Battle of Fort Donelson

- Battle of Fort Donelson: Brief Summary of Location, Strategies, and Casualties

- Battle of Fort Donelson – Bombardment

- Siege of Fort Donelson, 12–16 February 1862