Assault on Nijmegen (1702)

The assault on Nijmegen occurred during the War of the Spanish Succession, on 10 and 11 June 1702 involving French troops under the Duc de Boufflers against the small garrison and some citizens of the city of Nijmegen and an Anglo-Dutch army under the Earl of Athlone.

| Assault on Nijmegen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

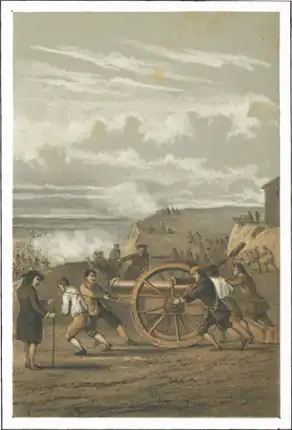

Citizens of Nijmegen operating the artillery to defend the city | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

37 battalions 59 squadrons[1] 25,000[2]-40,000 men[3] |

27 battalions 62 squadrons[1] 21,000[4]-23,000 men[2] Nijmegen garrison: 2 battalions[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 200-300 killed or wounded[2][5] | 700-1,000 killed, wounded or captured[2][5] | ||||||

In an attempt to save Kaiserswerth from capture by the Allies, Boufflers tried to force the numerically outnumbered army of Athlone into a battle by luring him away from his strong position, by attacking Nijmegen. The operation was a failure as the French were unable to take Nijmegen or to force Athone's army into a serious battle, despite inflicting more damage than received on the Allies during the skirmishes.[2][6]

Prelude

In May 1702, the Dutch Republic, England and the Holy Roman Emperor had declared war on France and the War of the Spanish Succession had begun. French troops had taken up positions in the Spanish Netherlands and in Germany before the war and were directly threatening the Dutch border.[7] An Allied army under the Prince of Nassau-Usingen began the siege of Kaiserswerth, in Germany, on 18 April to secure the eastern flank of the Dutch Republic.[8]

An Anglo-Dutch corps of 27 battalions and 62 squadrons, under Earl of Athlone, was camped near Kranenburg behind a strong entrenched position, while the French under Boufflers, with 37 battalions and 59 squadrons were camped near Sonsbeck. In the beginning of June the situation in Kaiserswerth began to get desperate for the defenders. Boufflers, with the intention to do a last attempt to save Kaiserwerth planned to force the numerically outnumbered army under Athlone into a battle by luring him away from his strong position. For this purpose he ordered a surprise attack on Nijmegen on 10 June.[9] Nijmegen, an important and strategically located Dutch city, with its recently modernised fortifications designed by Menno van Coehoorn, was garrisoned by only two infantry battalions and was ill-prepared for a French attack. If Athlone stayed behind in his strong position and left Nijmegen to fend for itself the city would have fallen in to French hands without much difficulty.[10]

The French assault

Although the French offensive was surprising, it was not entirely unexpected for the Allies. Several rumours had already warned of such an undertaking and in the early morning of 10 June news arrived in the Anglo-Dutch camp that the French army under Boufflers and the Duke of Burgundy, the Dauphin of France, were on the march. Still, Athlone's army remained in camp at Klarenburg until 8 o'clock in the evening, after which the necessity for a retreat was finally accepted. The artillery and baggage train were sent forward towards Nijmegen after which the infantry followed via Kranenburg en Groesbeek and the cavalry via Mook. As a French attack on Grave also had to be anticipated, Athlone sent four battalions to Grave.[11]

In the early morning of 11 June, cavalry vanguards caught sight of each other on the heath north of Mook. The French cavalry, reinforced with regiments under De Guiche was ordered to harry the Allied cavalry and to slow the retreat in anticipation of the French main force. Not long after, however, the French discovered that the entire Anglo-Dutch army was marching in battle order towards Nijmegen. The French cavalry followed at a short distance but did not dare to attack without infantry support. The latter joined the cavalry around 1 o'clock, but by then the army under Athlone had already reached the outworks of Nijmegen. The Anglo-Dutch infantry took up post in the covertway, while the cavalry took up a position on the glacis.[12]

For some hours, the armies remained in battle order facing each other without a major battle occurring. Some cavalry skirmishes took place, and gun and artillery fire was exchanged. The latter on the French side by the field artillery that had by now arrived and on the Dutch side by cannons, which the citizens had taken from the storehouse, brought to the ramparts and operated themselves.[13] The city was so poorly prepared for an attack that initially there were no artillery pieces in position on the ramparts, nor artillerymen, to operate them. It had also taken a long time before the artillery could be moved into position, as the keys to the storehouse could not be found.[3] Yet the brave behaviour of the citizens later earned them much praise.[14] The 'Kijk in de Pot' fortification to the south east of the city was taken twice by French cavalry but recaptured both times. But these fights too were nothing more than skirmishes. Boufflers and the Duke of Burgundy, now exposed to artillery fire from Nijmegen and incapable of forcing Athlone from his position decided to order a retreat around 5 o'clock in the afternoon.[15]

Aftermath

Allied losses were greater than those of the French. They lost about 700 men while the French lost around 200.[2] The French also captured 300 baggage wagons that the Allies had been unable to protect during the retreat. The French therefore presented the action at Nijmegen as a significant feat and a success for the French arms. The Duke of Burgundy's behaviour at his first feat was also praised. In reality, however, the operation was a failure. Although the French could thus indeed claim to have gotten the better of the Allies in the skirmishes, they were unable to take Nijmegen, to force Athone's corps into a serious battle or to break open the siege of Kaiserswerth.[2][16] A few days after repelling the assault, Kaiserswerth surrendered to the Allies.[3]

That Boufflers had not proceeded to an all-out assault had been partly due to the determined behaviour of the Allies. The Marquis de Quincy later wrote that: One cannot praise enough the firmness of one English and one Danish cavalry regiment that withstood the artillery fire without wavering. According to the historian Jan Willem Wijn, the retreat to Nijmegen counted as a striking testament to the excellent military qualities of the Dutch-English army. There are many examples in military history where such a retreat, under pressure from the enemy, degenerated into a flight.[6] Boufflers himself did not escape criticism. He was accused of excessive caution: according to the Duke of Berwick, talking and deliberating had robbed the French of the opportunity to take Nijmegen. It is possible, however, that the presence of France's heir apparent may have contributed to this caution.[6]

On 25 June, Marlborough was appointed commander of the combined Anglo-Dutch army in the Low Countries. The armies that had been commanded by Athlone and Nassau-Usingen were combined and reinforced with troops that had just arrived from England and Germany.[17] Marlborough, seeing himself at the head of 60,000 men, took advantage of his strong force by going on the offensive and penetrating into the Spanish Netherlands. Like Frederick Henry had done in 1632, the British commander followed the course of the river Meuse. The river was very important as a line of operation, because, due to the inadequacy of the land roads at that time, the possession of a river or a canal to transport an army's military necessities was not only advantageous, but almost necessary. The fortresses along the Meuse of Venlo, Stevensweert, Roermond and Liège succumbed to the Allies during this offensive.[18] The year had thus gone well for the Allies. But painful as the loss of these fortresses was for the French, the primary fortification lines of the Spanish Netherlands had not yet been broken.[19]

Sources

- Wijn, J.W. (1956). Het Staatsche Leger: Deel VIII Het tijdperk van de Spaanse Successieoorlog (The Dutch States Army: Part VIII The era of the War of the Spanish Succession) (in Dutch). Martinus Nijhoff.

- Van Lennep, Jacob (1880). De geschiedenis van Nederland, aan het Nederlandsche Volk verteld [The history of the Netherlands, told to the Dutch nation] (in Dutch). Leiden; z.j.

- Blok, P.J.; Molhuysen, P.C. (1914). "Reede-ginckel, Godard, baron van". Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek. Deel 3 (in Dutch).

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618–1905). Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- Knoop, Willem Jan (1861). Krijgs- en geschiedkundige geschriften. Deel 1 [Martial and historical writings. Volume 1] (in Dutch). H. A. M. Roelants.

- Lynn, John A. (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714. Longman. ISBN 0-582-05629-2.

- Périni, Édouard Hardÿ de (1906). Batailles françaises. [6e série] (in French). E. Flammarion (Paris). ISBN 978-2-01-613737-6.

References

- Wijn 1956, p. 95.

- Bodart 1908, p. 126.

- Van Lennep 1880, p. 239.

- Wijn 1956, p. 67.

- Périni 1906, p. 53.

- Wijn 1956, p. 99-100.

- Van Lennep 1880, p. 409-410.

- Wijn 1956, p. 43 & 49.

- Wijn 1956, p. 94-95.

- Van Lennep 1880, p. 238-239.

- Wijn 1956, p. 97.

- Wijn 1956, p. 97-98.

- Wijn 1956, p. 98.

- Blok & Molhuysen 1914, p. 1019.

- Wijn 1956, p. 98-100.

- Wijn 1956, p. 99.

- Wijn 1956, p. 109-110.

- Knoop 1861, p. 347.

- Lynn 1999, p. 275.