Ashes and Diamonds (film)

Ashes and Diamonds (Polish: Popiół i diament) is a 1958 Polish drama film directed by Andrzej Wajda, based on the 1948 novel by Polish writer Jerzy Andrzejewski. Starring Zbigniew Cybulski and Ewa Krzyżewska, it completed Wajda's war films trilogy, following A Generation (1954) and Kanal (1956). The action of Ashes and Diamonds takes place in 1945, shortly after World War II. The main protagonist of the film, former Home Army soldier Maciek Chełmicki, is acting in the anti-Communist underground. Maciek receives an order to kill Szczuka, the local secretary of the Polish Workers' Party. Over time, Chełmicki increasingly doubts if his task is worth doing.

| Ashes and Diamonds | |

|---|---|

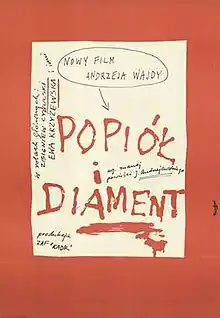

1958 Polish poster by Wojciech Fangor[1] | |

| Popiół i diament | |

| Directed by | Andrzej Wajda |

| Screenplay by | Jerzy Andrzejewski Andrzej Wajda |

| Based on | Ashes and Diamonds 1948 novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski |

| Starring | Zbigniew Cybulski Ewa Krzyżewska Wacław Zastrzeżyński |

| Cinematography | Jerzy Wójcik |

| Edited by | Halina Nawrocka |

| Music by | Filip Nowak |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Janus Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | Poland |

| Language | Polish |

Ashes and Diamonds, although based on the novel that directly supported the postwar Communist system in Poland, was subtly modified in comparison with the source material. Wajda sympathized with the soldiers of the Polish independence underground; thus, he devoted most of the attention to Chełmicki. During the three-month development of Ashes and Diamonds, the director made drastic changes to the baseline scenario, thanks to his assistant director Janusz Morgenstern, as well as Cybulski, who played the leading role. The film received permission from the authorities to be distributed only through Andrzejewski's intercession. The film did not receive permission to be screened at the main competition at the Cannes Film Festival. However, Ashes and Diamonds appeared at the Venice Film Festival, where it won the FIPRESCI award.

At first, Ashes and Diamonds met positive critical reception, both in Poland and worldwide. However, after the Revolutions of 1989, it was criticized for falsifying the collective memory of Polish partisans. Nevertheless, the film has maintained its reputation as one of the most famous Polish motion pictures in history.

Plot

On 8 May 1945, at the end of World War II, near a small country church, former Home Army soldiers, Maciek, Andrzej and Drewnowski, prepare to assassinate Konrad Szczuka, a political opponent and a secretary of Polish Workers' Party. The ambush fails, as the attackers later learn that they have mistakenly killed two innocents.[2]

Andrzej and Maciek's superior, Major Waga, learns of the failed assassination attempt. Waga orders Andrzej and Maciek to attempt the mission for a second time. They come to the Hotel Monopol Restaurant, where a banquet in honour of the victorious war begins, but the combatants do not participate. While sitting in the bar, Maciek and Andrzej listen to the song "The Red Poppies of Monte Cassino" and reminisce over their fallen comrades. In honour of them, Maciek lights several glasses of rectified spirit on fire. Their hapless comrade Drewnowski gets drunk at the bar, where he discusses career prospects in postwar Poland with Pieniążek, a representative of the democratic press.[3]

During the party, he has a flirtatious conversation with a barwoman named Krystyna and invites her to his room. Afterwards, Maciek goes to his hotel room to check his gun. Krystyna comes to his room after her shift ends. As they lay naked in bed, they realize they are in love, but Krystyna doesn't want to become attached as Maciek doesn't plan to stay in town for long. They decide to go for a walk. It begins to rain, so Krystyna and Maciek decide to find shelter in a ruined church. Krystyna notices a poem inscribed on the wall, and Maciek recites it from memory in a somber tone. The lovers say their goodbyes, with Maciek promising he's going to try to "change things" so he can stay with her.

Maciek returns to the bar where he discusses his sense of duty and obligation to the cause with Andrzej. However, Andrzej is unsympathetic to his plight and says Maciek will be a deserter if he does not fulfill his obligation to assassinate Szczuka. Meanwhile, a completely drunk Drewnowski spoils the banquet, covering the other guests with foam from a fire extinguisher, and leaves the ball in shame with his intended career as a Communist functionary in ruins. After the reception, Szczuka learns that his son Marek has been arrested for joining an underground militia.[4]

Maciek waits for Szczuka to leave the hotel to meet his captured son, follows him, and shoots him to death. The next morning, Maciek plans to leave Ostrowiec by train. He tells Krystyna that he was unable to "change things," leaving her heartbroken. She tells him to leave without saying another word, which he does. The hotel guests dance to a pianist and band playing Chopin's "Military" Polonaise in A Major. On the way to the train station, Maciek observes Andrzej beating Drewnowski for his newfound, opportunistic support for the underground. Maciek flees when Drewnowski calls his name. He accidentally runs into some soldiers of the Polish People's Army and draws his pistol in panic. They shoot and fatally wound him. Maciek escapes to a garbage dump, but he collapses and dies in agony.[5]

Cast

- Zbigniew Cybulski as Maciek Chełmicki

- Ewa Krzyżewska as Krystyna

- Wacław Zastrzeżyński as Szczuka

- Adam Pawlikowski as Andrzej

- Bogumił Kobiela as Drewnowski

- Stanisław Milski as Pieniążek

- Ignacy Machowski as Waga

Production

Writing

Ashes and Diamonds is loosely based on the novel by Jerzy Andrzejewski, published for the first time in 1948.[6] The novel was a mandatory school set book in communist Poland and enjoyed respect among the contemporary authorities.[7] The first directors who tried to adapt the book into a film were Erwin Axer and Antoni Bohdziewicz. In Axer's script, which adhered to the spirit of the original, the roles were supposed to be more like caricatures. Historian Tadeusz Lubelski retrospectively commented on Axer's script with the following words: "Communists are even more decent and busy, aristocrats and former Home Army members – even more vile and reckless."[8] Bohdziewicz's script contained a similar propaganda message, depicting the command of the Polish resistance in a bad light. There, Major Waga blackmailed Maciek to kill Szczuka, threatening him with a war trial; in the end, Maciek decided to support Szczuka.[9] However, none of these scripts were implemented, and policymakers considered Bohdziewicz's vision too "defensive."[10] Jan Rybkowski also planned to direct an Ashes and Diamonds adaptation, though he eventually decided to focus on a comedy titled Kapelusz pana Anatola (Mr. Anatol's Hat). Thus, he gave Andrzej Wajda an opportunity to launch a project.[11]

In November 1957, Wajda carried out a letter conversation with Andrzejewski, during which the future director suggested several changes to the initial version of the story. A thread which concerned the judge Antoni Kossecki was deleted so that the main plot focused on the confrontation between Maciek and Szczuka. Also, Wajda suggested that the story be condensed to only one day, with Maciek acting as the central hero.[12][10] Wajda and Andrzejewski completed the screenplay in January 1958, giving it for scrutiny to the Commission for Screenplay Assessment. After long consideration, the Commission, whose members were Aleksander Ścibor-Rylski, Andrzej Braun, Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz, Tadeusz Konwicki and Andrzej Karpowski, decided to vote for the screenplay's acceptance.[13]

Development

Having the screenplay accepted, Wajda prepared for the development of Ashes and Diamonds within the "KADR" Film Unit. At first, the director intended to shoot the film in Łódź. However, he finally chose an atelier in Wrocław, the decision made due to possible savings and to prevent the policymakers from intervening too much in the film development. On 3 February 1958, the acting Chief of Cinematography Jerzy Lewiński decided to start the production of Ashes and Diamonds, without consulting the authorities.[14] The contract for the commission guaranteed Wajda a salary of 69,000 Polish zloty, whereas Andrzejewski received 31,500 Polish zloty.[14] The overall budget of Ashes and Diamonds is estimated at 6,070,000 Polish zloty.[15]

Wajda then began gathering the film crew. Stanisław Adler became the producer, whereas Jerzy Wójcik took the cinematography, and Filip Nowak was commissioned to select music material for the film.[16] It was decided that Ashes and Diamonds be first filmed in the atelier, then in the open air.[17] The main scenography made in the atelier represented the Monopol Hotel restaurant. However, the film crew did also use authentic locations, such as the St. Barbara's Church in Wrocław and a chapel near Trzebnica.[15]

The director experienced some issues with the selection of the future cast. However, he found support in the person of Janusz Morgenstern, his assistant director. Morgenstern, more familiar with the acting market, encouraged Wajda to put Zbigniew Cybulski in the role of Maciek, although the director considered the candidature of Tadeusz Janczar.[18] Having come to the film set, Cybulski instantly refused to play in a partisan uniform suggested by costume designer Katarzyna Chodorowicz, and insisted on wearing his "fifties' style dark glasses, jacket and tight jeans."[19] Wacław Zastrzeżyński, a theatrical actor with barely any film experience, was cast as Szczuka.[20] Adam Pawlikowski, a musicologist, took the role of Andrzej, whereas Cybulski's colleague Bogumił Kobiela was cast as Drewnowski.[21]

Filming

Photography for Ashes and Diamonds started in March 1958, and finished in June 1958, after 60 shooting days.[22] The film was shot in 1:1.85 format, which had never been used before in Polish cinema.[23] During filming, the crew made crucial changes in the scenario, which affected the future reception of the film. For example, Cybulski suggested that Szczuka should hold Maciek while dying; Wajda added scenes containing Christian iconography; and Morgenstern invented the most widely known scene, during which Maciek and Andrzej light up the glasses filled with the rectified spirit.[24] The ending was changed, too; Wajda cut down the scene from the novel, during which some soldiers of Polish People's Army commented on Maciek's death with following words: "Hey, you, ... what made you run away?"[25][24]

The most troublesome task was to convince the communist authorities to display Ashes and Diamonds. Party intellectuals were dissatisfied with making Maciek Chełmicki the main character of the film. It was then that Andrzejewski himself, who–with the support of his fellow writers–convinced PZPR activists that the ideological message of the film was correct; without the help of the author of the novel, Wajda's work would have never been released.[26] The official screening took place on 7 July 1958, after which Ashes and Diamonds could be distributed in cinemas.[27] Despite the protests of Aleksander Ford, who demanded that the authorities ban the film, its official premiere took place on 3 October 1958.[28] Nevertheless, due to the still existing doubts about its message, Ashes and Diamonds were banned from taking part in the main competition of the Cannes Film Festival.[29] Then Lewiński sent Wajda's work to the Venice Film Festival, where–apart from the main competition–it won the award of the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI).[30]

Reception

Ashes and Diamonds was an international success. According to Janina Falkowska, this is Wajda's most recognizable film,[31] and–in the opinion of Marek Hendrykowski–the most important achievement of the Polish Film School, which highlights the director's characteristic style, while dealing with the Second World War.[31] Despite the condemnation of the film by some Communist critics, many supporters of independent Poland identified themselves with the role of Maciek.[31] Cybulski has been compared to James Dean in his performance, which was complemented by the fact that with his appearance, Polish actor personified the contemporary generation of the 1950s.[32] In total, around 1,722,000 spectators watched Ashes and Diamonds during the opening year.[33]

Critical reception in Poland

Polish film critics generally were delighted with the film adaptation of Andrzejewski's novel. Stanisław Grzelecki assessed Ashes and Diamonds as "a new, outstanding work of Polish film art."[34] According to Krzysztof Teodor Toeplitz, "Ashes and Diamonds is not a brilliant film, but it is certainly a great film".[34] Jerzy Płażewski called Wajda's film "excellent."[34] Several other Polish film and literary critics–Stanisław Grochowiak, Stanisław Lem, Andrzej Wróblewski–also considered Ashes and Diamonds an exceptional work.[34]

In the foreground, due to the then-prevailing Communist system, among the issues discussed by critics were attempts at ideological interpretation. The tragic actions of Home Army soldiers, who supposedly unjustly continued their struggle against the new political reality, were pointed out at that time. These voices, however, included Jan Józef Szczepański's opinion, which was devoid of ideological tone. In his opinion, Wajda showed the viewer the qualities of Polish young people during the war.[35] Simultaneously, critics connected with the authorities had doubts about whether the director would not glorify this generation, which would induce the audience's solidarity with the "reactionary" soldier. Zygmunt Kałużyński and Wiktor Woroszylski had the greatest complaints about Ashes and Diamonds. Kałużyński sought an anachronism in the portrait of Maciek's persona, considering its styling more appropriate for contemporary times than for 1945. In turn, according to Woroszylski, "the Home Army soldiers have been endowed with such a clear sense of the absurdity of their misdeeds that [...] it's hopeless."[35] Marxist reviewers criticized Ashes and Diamonds, highlighting its alleged lack of educational functions and the marginalization of Szczuka, who was depicted in the film as a mediocre party activist. Stanisław Grochowiak, who found in Wajda's drama the "eschatological dimension" of the classical tragedy, rejected such propagandist interpretations.[35]

Critics looking for aesthetic issues in Wajda's work have interpreted it in a different way. Jerzy Kwiatkowski noted the high expression of adaptation in comparison with the original. Alicja Helman, in turn, put forward the opinion that "there is everything in this film–too much, too good, too beautiful", but at the same time it emphasizes "zeal, anxiety, takeover, great emotional passion".[36] Ernest Bryll devoted a broader analysis to the evaluation of the antique structure of film work, with an inseparable fate showing the tragedy of the main character's actions.[36] The role of Zbigniew Cybulski, as well as the musical arrangement and the cinematography of Jerzy Wójcik, were widely accepted.[37]

After the Revolutions of 1989, Ashes and Diamonds faced the accusations of falsifying history. Andrzej Werner accused the film of a historical lie,[38] while film critic Waldemar Chołodowski criticized Wajda's work for suggesting that the representatives of the underground should be isolated from society.[39] Krzysztof Kąkolewski deplored the fact that Wajda's Ashes and Diamonds for Polish and international audiences were for years a source of knowledge about the times after the Second World War. However, he also noted that the director–in contrast to the author of the original–toned down the propagandist message of the book, in which the underground soldiers were directly depicted as bandits.[40] Conversely, Tadeusz Lubelski stated that Wajda's version warms the image of the underground to a much greater extent than the ones proposed by Axer and Bohdziewicz. Unlike Kąkolewski, Lubelski was convinced that the moment of the Polish October was perfectly captured during the shooting of the film.[41]

Critical reception outside Poland

In Western Europe, Ashes and Diamonds was widely praised by film critics. The Italian critic Nevio Corich found in the film a lyrical reference to Baroque art.[42] Some film experts, such as Fouma Saisho, pointed to the poetic qualities of the work. Georges Sadoul compared Wajda's work to those of the prominent director Erich von Stroheim.[42] In his 1999 retrospective review for The Guardian, Derek Malcolm compared Maciek's death to the ending of Luis Bunuel's Los Olvidados.[43] However, some critics were irritated by the alleged mannerism of the work and the exposition of Baroque ornamentation.[42] Dave Kehr from Chicago Reader shared an opinion that "[f]ollowing the art cinema technique of the time, Wajda tends toward harsh and overstated imagery,"[44] while the Time Out London review stated that "Wajda's way is the sweet smell of excess, but some scenes remain powerfully memorable – the lighting of drinks on the bar, the upturned Christ in a bombed church, and Cybulski's prolonged death agonies at the close."[45] As David Parkinson from Empire said, "[Wajda's] final installment of the classic Polish trilogy is heavy in symbolism but remains affective and intimate viewing."[46]

Awards and nominations

Ashes and Diamonds received the FIPRESCI Prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1959.[47] The film was also nominated twice for the British Academy of Film and Television Arts award, with Zbigniew Cybulski nominated in the "Best Actor" category and Andrzej Wajda nominated in the "Best Film from any Source".[48][49]

Legacy

Ashes and Diamonds is considered by film critics to be one of the great masterpieces of Polish cinema and arguably the finest film of Polish realist cinema.[50] Richard Peña in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die considers the ending of the film to be one of the most powerful and often quoted endings in film history.[50] The film was ranked #38 in Empire magazines "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2019.[51] In the 2015 poll conducted by Polish Museum of Cinematography in Łódź, Ashes and Diamonds was ranked as the third greatest Polish film of all time.[52] Directors Martin Scorsese, Hayao Miyazaki, Francis Ford Coppola, Paweł Pawlikowski and Roy Andersson have listed it as one of their favourite films of all time.[53][54][55][56]

In 2013 Martin Scorsese selected it for screening alongside films such as Innocent Sorcerers, Knife in the Water, The Promised Land and Man of Iron in the United States, Canada and United Kingdom as part of the Martin Scorsese Presents: Masterpieces of Polish Cinema festival of Polish films.[57]

Ashes and Diamonds had a significant impact on the development of the Polish Film School, causing a polemical reaction from other directors of the movement. In 1960, one of its members, Kazimierz Kutz, directed a polemical film entitled Nobody Cries (Nikt nie woła, 1960). Unlike Maciek Chełmicki, the protagonist of this film–also a soldier of the independence underground–does not carry out the order, but tries to start life anew and settle in the Recovered Territories.[58] In How to Be Loved (1961), Wojciech Jerzy Has made a pastiche of an iconic "scene with lamps". Here, Cybulski's character is not a conspirator ready to act, but an unshaven, drunken mythomaniac recalling his alleged heroic deeds.[59]

The myth of Cybulski also resounded in Wajda's later films. In his works Landscape After the Battle (1969) and The Wedding (1972), there is a renewed reference to the final dance.[60] Under the influence of criticism from conservative reviewers, the director made The Crowned-Eagle Ring (Pierścionek z orłem w koronie, 1992). This work included self-plagiarism of the scene of lighting glasses in a bar (Cybulski was imitated by Tomasz Konieczny, while Rafał Królikowski embodied Adam Pawlikowski), but the scene was set in a different, self-ironic context.[61] However, while conservative circles regarded Wajda's The Crowned-Eagle Ring as a fair settlement of accounts with the past period,[62] the film aroused embarrassment among liberal critics, with Jakub Majmurek writing about "the most painful aesthetic self-disgrace" on the part of the director.[63]

Former Pink Floyd frontman Roger Waters claims that Ashes and Diamonds had "an enormous impact" on him as a young man,[64] and the lyrics of the Pink Floyd song "Two Suns in the Sunset" from the band's 1983 album The Final Cut makes references to the film.[65]

After watching the film Ashes and Diamonds for several times at Oslo in 1960, theatre director Eugenio Barba decided to go to Poland for his further studies in directing. He enrolled his name at Warsaw University but could not complete his studies and did apprenticeship with Jerzy Grotowski. Barba had written a book on his experiences in Poland under the name Land of Ashes and Diamonds (1999).[66]

Recognition

| Year | Presenter | Title | Rank | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | Movieline | 100 Greatest Foreign Films | N/A | [67] |

| 2001 | Village Voice | 100 Best Films of the 20th Century | 86 | [68] |

| 2005 | John Walker | Halliwell's Top 1000: The Ultimate Movie Countdown | 63 | [69] |

| 2019 | Empire | The 100 Best Films of World Cinema | 38 | [70] |

| 2018 | Derek Malcolm | A Century of Films: Derek Malcolm's Personal Best | N/A | [71] |

| 2018 | BBC | The 100 Greatest Foreign-Language Films | 99 | [72] |

See also

Notes

- "Seven countries, seven posters, one classic film". British Film Institute. May 18, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- Falkowska 2007, pp. 54–55.

- Falkowska 2007, pp. 55–56.

- Falkowska 2007, pp. 56–58.

- Falkowska 2007, pp. 59–60.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 13–18.

- Coates 1996, pp. 288.

- Lubelski 1994, p. 177.

- Lubelski 1994, p. 182.

- Lubelski 1994, p. 184.

- Lubelski 1994, p. 176.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 20–29.

- Coates 2005, p. 39.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 45.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 50.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 50–51.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 54.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 87–89.

- Shaw 2014, p. 50.

- Lubelski 2000, p. 166.

- Lubelski 2000, pp. 166–167.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 103.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 286.

- Lubelski 1994, p. 186.

- Andrzejewski 1980, p. 239.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 316.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 317.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 318–319.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 320–321.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 378–379.

- Falkowska 2007, p. 60.

- Haltof 2002, p. 89.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 413.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 343–347.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 348–362.

- Kornacki 2011, pp. 363–369.

- Kornacki 2011, p. 369.

- Werner 1987, pp. 32–45.

- Lubelski 2000, p. 157.

- Kąkolewski 2015, pp. 17–21.

- Lubelski 1994, pp. 185–187.

- Falkowska 2007, p. 62.

- Malcolm 1999.

- Kehr 2017.

- Time Out London.

- Parkinson 2006.

- "Popiół i diament". FilmPolski (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Best Film from any Source". BAFTA Awards. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Foreign Actor in 1960". BAFTA Awards. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Schneider 2012, p. 350.

- "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema – 38. Ashes and Diamonds". Empire.

- "Polska – Najlepsze filmy według wszystkich ankietowanych". Muzeum Kinematografii w Łodzi (in Polish). 2015-12-28. Archived from the original on 2017-10-08. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- "Scorsese's 12 favorite films". Miramax.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- "They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? Hayao Miyazaki Director Profile".

- Lussier, Germain (2012-08-03). "Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, Francis Ford Coppola and Michael Mann List The Best Movies Ever". Slash Film.

- "Roy Andersson | BFI". www2.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "UK Film List / Martin Scorsese Presents". mspresents.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- Lubelski 2015, p. 979.

- Lubelski 2015, p. 252.

- Garbicz 1987, p. 323.

- Falkowska 2007, pp. 63–64.

- Kąkolewski 2015, pp. 67–68.

- Majmurek 2013, p. 9.

- ""Solidarność" jest przykładem dal reszty świata". Interia.pl. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "The European Masterpieces Part 3: Ashes and Diamonds (1958 Andrzej Wajda)". Momentary Cinema. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Barba, Eugenio. Land of Ashes and Diamonds: My Apprenticeship in Poland, Followed by 26 Letters from Jerzy Grotowski to Eugenio Barba, translated by Judy Barba and Eugenio Barba. Aberystwyth: Black Mountain Press, 1999.

- "100 Greatest Foreign Films from Movieline Magazine". www.filmsite.org. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "100 Best Films - Village Voice". 2014-03-31. Archived from the original on 2014-03-31. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- Pendragon, The (2017-09-28). "Halliwell's Best 1000 Films". The Pendragon Society. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Empire. 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2022-11-15.

- Pendragon, The (2018-07-22). "Derek Malcolm's Top 100 Films of the Century". The Pendragon Society. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- "The 100 greatest foreign-language films". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

References

- Andrzejewski, Jerzy (1980). Ashes and diamonds. Harmondsworth, Eng. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-005277-1.

- "Ashes and Diamonds, directed by Andrzej Wajda - Film review". Time Out London. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Coates, Paul (1996). "Forms of the Polish Intellectual's Self-Criticism: Revisiting Ashes and Diamonds with Andrzejewski and Wajda". Canadian Slavonic Papers. Informa UK Limited. 38 (3–4): 287–303. doi:10.1080/00085006.1996.11092126. ISSN 0008-5006.

- Coates, Paul (2005). The Red and the White: The Cinema of People's Poland. Film Studies. Wallflower. ISBN 978-1-904764-26-7. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- Falkowska, Janina (2007). Andrzej Wajda: History, Politics, and Nostalgia in Polish Cinema. Berghahn Series. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-508-8. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- Garbicz, Adam (1987). Kino, wehikuł, magiczny: przewodnik osiągnięć filmu fabularnego (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. ISBN 978-83-08-01377-9. OCLC 442677119.

- Haltof, Marek (2002). Polish National Cinema. New York – Oxford: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571812759.

- Kąkolewski, Krzysztof (2015). Diament odnaleziony w popiele (in Polish). Poznan: Zysk i S-ka Wydawnictwo. ISBN 978-83-7785-456-3. OCLC 904779553.

- Kehr, Dave (2017-12-14). "Ashes and Diamonds". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Kornacki, Krzysztof (2011). Popiół i diament Andrzeja Wajdy (in Polish). Gdańsk: Słowo/obraz terytoria. ISBN 978-83-7453-858-9.

- Lubelski, Tadeusz (1994). "Trzy kolejne podejścia". Kwartalnik Filmowy. 6: 176–187.

- Lubelski, Tadeusz (2000). Strategie autorskie w polskim filmie fabularnym lat 1945-1961 (in Polish). Kraków: Rabid. ISBN 83-912961-7-2.

- Lubelski, Tadeusz (2015). Historia kina polskiego, 1895-2014. Kraków: Towarzystwo Autorów i Wydawców Prac Naukowych Universitas. ISBN 978-83-242-2707-5. OCLC 941070158.

- Majmurek, Jakub (2013). Wajda: Przewodnik Krytyki politycznej (in Polish). Warszawa: Wydawn. Krytyki Politycznej. ISBN 978-83-63855-22-2. OCLC 859832990.

- Malcolm, Derek (1999-05-05). "Andrzej Wajda: Ashes and Diamonds". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Parkinson, David (2006-03-24). "Ashes and Diamonds". Empire. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- Schneider, Steven Jay (2012). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die 2012. Octopus Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-84403-733-9.

- Shaw, Tony (2014). Cinematic Terror: A Global History of Terrorism on Film. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-5809-3.

- Werner, Andrzej (1987). Polskie, arcypolskie (in Polish). London: Polonia. ISBN 0-902352-60-1. OCLC 716217264.

External links

- Ashes and Diamonds at IMDb

- Ashes and Diamonds at AllMovie

- Ashes and Diamonds at the TCM Movie Database

- Ashes and Diamonds an essay by Paul Coates at the Criterion Collection