Armée Indigène

The Indigenous Army (French: Armée Indigène), also known as the Army of Saint-Domingue (French: Armée de Saint-Domingue) or Lame Endijèn in Haitian Creole, was the name bestowed to the coalition of anti-slavery men and women who fought in the Haitian Revolution in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Encompassing both black slaves, maroons, and affranchis (black and mulatto freedmen alike),[1] the rebels were not officially titled the Armée indigène until January 1803, under the leadership of then-general Jean-Jacques Dessalines.[2] Predated by insurrectionists such as François Mackandal, Vincent Ogé and Dutty Boukman, Toussaint Louverture, succeeded by Dessalines, led, organized, and consolidated the rebellion. The now full-fledged fighting force utilized its manpower advantage and strategic capacity to overwhelm French troops, ensuring the Haitian Revolution was the most successful of its kind.

| Armée indigène | |

|---|---|

Jean-Jacques Dessalines Coat of arms | |

| Active | August 1791 – 1915 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Saint-Domingue (1791–1803) Haiti (1804–1915) |

| Type | Land forces |

| Size | approximately 160,000 (including volunteers) |

| Motto(s) | Liberté ou la Mort, ,Libète oswa Lanmò |

| Colors | Le Bicolore |

| March | Grenadiers a l'assaut! ,Alaso |

| Engagements | Battle of Croix-des-Bouquets 1st Siege of Port-au-Prince Battle of Cap-Français (1793) Capture of Fort-Dauphin (1794) Battle of the Acul Battle of Gonaïves Battle of Port-Républicain Battle of Saint-Raphaël Battle of Jean-Rabel War of Knives Saint-Domingue expedition Battle of Ravine-à-Couleuvres Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot 2nd Siege of Port-au-Prince (1803) Blockade of Saint-Domingue Action of 28 June 1803 (Môle-Saint-Nicolas) Battle of Vertières |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-chief | Toussaint Louverture (1791-1802) Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1803–06) |

| Notable commanders | Alexandre Pétion Henri Christophe François Capois Étienne Élie Gerin Magloire Ambroise Jacques Maurepas Sanité Belair Augustin Clerveaux |

Etymology

Despite its name, the moniker had no relation to the indigenous populations of Hispaniola, as the native Taíno people no longer existed in any discernible number at the advent of the Haitian Revolution. Rather, the word indigène was used in French as a euphemism for non-white (cf. indigénat). Although the term indigène in French refers to the native of the land, Dessalines utilized that term to separate themselves from the French philosophy and slave-based economy and to galvanize the affranchi, bossale, and creoles around one common goal, the independence of Hayti. A precedent to the term indigène was Dessalines' first army known as Armée des Incas referring to the Inca Empire in South America. The finality of the term happened on January 1, 1804, when Dessalines restore the native name of the Island from St-Domingue to Hayti and later on in the speech he declared by chasing out the French troops he then avenges the Americas.

History

Pre-Haitian Revolution and context

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, the French colony of Saint-Domingue, later established as Haiti post-revolution, was founded on the western half of the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean. An agriculturally potent landmass, France regarded the colony as a highly valuable asset and the shining star of its imperial crown, producing most of the world's sugar and coffee by the 1780s.[1] A forced labor plantation economy, historians note that the chattel slavery established within the colony was brutal, with torture being commonplace.[3] Disease, such as yellow fever, was epidemically prevalent, contributing to the high slave mortality rate. In efforts to save money, some plantation owners hastened the death of sickly slaves through intentional starvation, aware that replacements would be shipped to the colony.[2][4] Enforced by the Code Noir, these cruel living conditions led the slaves to conspire to revolt, eventually forming the Armée Indigène. Enveloped in inhumane treatment, many slaves found solace in Vodou,[1][5] though always in a conciliatory fashion, as the practice was explicitly banned by plantation owners.

Despite their free status, the gens de couleur were unprotected from discrimination. Petits blancs (poor whites) resented the gens de couleur because of their wealth and power, gained by the ability to buy other slaves. In 1789, The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen gave hope to the gens de couleur that France would look at every citizen equally, regardless of position or race, giving them better living conditions and rights.[6] However, the vague interpretation of the Declaration would leave the gens de couleur's social position unchanged. In fact, the grand blancs would take advantage of the Declaration and use it to gain independence from trade regulations. In addition, slavery was not officially abolished. Since the 1780s, free men of color such as Julien Raimond and Vincent Oge had tried to get free people of color the rights that belonged to them by representing the colonies in the National Assembly. One of these rights was the right to vote; however, free people of color were still denied of this right.

With 300 armed gens de couleur and affranchis, Vincent Oge led an insurrection, which attempted to disarm the white men of Grande-Rivière.[7][8] Taking place on 29 October 1790, this event became known as the Oge Rebellion, and ended in failure. Oge and his rebels were executed on the wheel, and his barbaric death would cause even more tension amongst the free people of color and eventually the enslaved, who already had the mindset of revolution.[7][8]

Maroon War

By the end of the 18th century, a century after the Treaty of Ryswick the social tension in St-Domingue have reach a level enough, and the different maniel or doco (independent maroon communities) have gained a level of organization all around the island to start a revolution.

- Plaine-du-Nord, in the Grand-Nord region, Dutty Boukman, and Cecile Fatiman commanded thousand of maroon and rebel slave to ravage the crops;

- Plaine du-Cul-de-Sac, in the West region, Sanglaou;

- Plaine de Léoganes and Jacmel, in West region, Romaine-la-Prophétesse

- Plaine des Cayes, in the Tiburon Peninsula region, the Macaya-Marrons attacked the city of Les Cayes for closed to a year.

- Massif the Baoruco (Massif de la Selle and Sierra the Baoruco), Lamour Dérance, a maroon hostile to both Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

In 1803 the marrons leaders Sansousi and Lamour Dérance and troops were formally incorporated in the Armée Indigène.

The first mass rebellion broke out in August 1791, when religious Vodoun priest ougan-sanba Dutty Boukman ordered the slaves to attack Bois Caïman. While they were seeking their rights as Frenchmen, the slaves also engaged in acts of cruelty, such as rape, poison, and murder against the white plantation owners. In a couple of weeks, the number of slaves participating in the rebellion was over 100,000. By 1792, a third of Saint-Domingue was under the control of the rebels, and France was ready to quell the rebellion.[9]

The maroons of Haiti military style and role in the indigenous army are similar to the Mountain Troops of France and the Swiss army. However, an underlying issue existed between the maroon troops and the creole troops relating to the respect of command. The maroon also called Congo troops did not organize their troops based on established corps such as infantry, cavalry, or artillery but based on ethnic groups. Some of the most famous groups are the:

- Dawonmen from the Dahomey and Allada kingdoms are known for their commanding and strategic skills. Toussaint Louverture's father Gaou Ginou was an Allada prince

- Nago from the Yoruba kingdom in Nigeria are known for their tenacity

- Ibo from the Igbo people of Nigeria are known for their tenacity and pride

- Bizango from the Bissagos Islands and Guinea-Bissau are known for their tenacity

- Congo from the Kongo kingdom are known for their knowledge of natural remedies

Gens de Couleur rights

While the blacks are fighting for the end of slavery the mulattos was asking France to recognize them as full citizen and give them the right to participate in the colony's political life. The wealthy gens de couleur were given citizenship in May 1791, which caused tension between them and the grands blancs, and as a result, fighting broke out between the two groups. Because of this, the poorer gens de couleur, like the slaves, were also resentful of grands blancs, who were in the way of what was the beginning of equality for everyone in Saint-Domingue. They gave political rights to the gen de couleur, and sent Léger-Félicité Sonthonax to Saint-Domingue as its new governor; he was a man against slavery and the plantation owners. Many gens-de-couleur gained military experience within the Chasseurs-Volontaires de St-Domingue by participating in the Savannah Battle alongside the Americans against the British, this situation would help in the War of Knives when the British Navy would block the supply of the French troops in favor of Toussaint's Army. The period reach its height when the mulatto commander like Pétion, Beauvais, Pinchinnat, and more gained the battle of Pernier.

For the accomplishment of these civil rights, a corps of fewer than 300 men, 197 blacks and 23 mulattoes known as the Swiss was promised freedom at the end. Unfortunately, they were captured and brought to Jamaica, near Port-Royal to be sold where they refused to buy them. They were then brought to Mole St-Nicolas and executed by whites from l'Artibonite known as Saliniers.

War of Knives

While all of this was happening, Toussaint Louverture was training his own army in the ways of guerilla warfare, and helping the Spanish, who declared war against France in 1793; various outside powers assisted the Haitian insurgents during the early years of the revolution in hopes that they could take over Saint-Domingue from the French amidst the confusion of the French Revolutionary Wars. Louverture, alongside Dessalines and his army, would go back to the French in 1794, a while after France abolished slavery in the colonies.[7][10]

By 1798, Toussaint and Rigaud had jointly contained both external and internal threats to the colony. In April 1798, British commander Thomas Maitland approached Toussaint to negotiate a British withdrawal, which was concluded in August.[5] In early 1799, Toussaint also independently negotiated "Toussaint's Clause" with the United States government, allowing American merchants to trade with Saint-Domingue despite the ongoing Quasi-War between the U.S. and France.

In July 1798, Toussaint and Rigaud traveled in a carriage together from Port-au-Prince to Le Cap to meet the recently arrived representative Théodore-Joseph d'Hédouville, sent by France's new Directory regime. Oral tradition asserts that during this carriage ride, Toussaint and Rigaud made a pact to collaborate against Hédouville's meddling. However, those efforts soon came undone, as Hédouville intentionally treated Rigaud with more favor than Toussaint, in an effort to sow tension between the two leaders. In a letter to Rigaud, Hédouville criticized "the perfidy of General Toussaint Louverture" and absolved Rigaud of Toussaint's authority as general-in-chief. He invited Rigaud to "take command of the Department of the South".[9] Hédouville eventually fled Saint-Domingue, sailing from Le Cap in October 1798 due to threats by Toussaint resulting in a year fight between the two generals.

Following his victory over Rigaud, Toussaint declared a general amnesty in July 1800. But Toussaint's general Jean-Jacques Dessalines became infamous during this period for carrying out brutal reprisals and massacres against Rigaud's supporters. Some historians have asserted that Toussaint himself ordered massacres, but delegated the killing to his generals to avoid culpability.[19] Many of Rigaud's generals were exiled to France and some to Cuba.

Later, Louverture would establish a Haitian constitution the Constitution of 1805 being the first constitution to abolish slavery and declared himself governor for life.

Expedition of St-Domingue

Napoleon Bonaparte did not accept this claim, and sent a troop of more than 30 000 men under the leadership of his brother-in-law Charles-Victor Emmanuel Leclerc. When the troops arrived in St-Domingue many Haitian generals refused to give access to the French navy to disembark and famously Henry Christophe rather burned the city on their commandment than betray Toussaint. After the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot in Petite-Rivière de L'Artibonite, the French realized they can not win against Louverture on the battlefield and decided to use a ruse to capture him. They invited him to a meeting in Gonaives, where he was captured and put on a boat Creole to Cap-Francais et another boat le Héros to Brest in Francelocked up Louverture, where he would die in Fort de Joux.[7][10]

Organization of the troop

After the Haitians discover the secret plan of the French was to reinstate slavery and killed all males over the age of 14 both the old Toussaint's troops and Rigaud's troops. This is the last step toward the Independence of Hayti but many obstacles were on the way to glory, notably the disorganization of the Haitian troops. In 1802 Pétions left the French side and meet J-J Dessalines in Plaisance to convince him to lead the Armée Indigène. After that Dessalines traveled all over the North to organize the troops of Clerveaux, Christophe, and Cappois. From May 14 to May 18, 1803, he then went to Arcahaie to organize the troops of the West with Gabart, Vernet, Pétion, Magloire Ambroise , and Cangé. Finally, on July 5, 1803, he was in Camp-Gérard outside of the city of Les Cayes to organize the troops in the South under the leadership of Nicolas Geffrard, Laurent Férou, Étienne Gérin.

Thus the Indigène Army is formed from the union of the Chasseurs-Volontaires de St-Domingue, the Legion of Equality of the South, Armée Coloniale of Toussaint Louverture, and some Maroon's followers of Lamour Dérance and Sansousi.

These series of meetings culminated in the renaming of the army, Armée Indigène, and the basis of the Haitian flag. Saint-Domingue's flag changed to a red and blue flag with the slogan “Liberte a la Mort” (Liberty or Death) in white lettering.[2] Bonaparte would try to reestablish the slave regime by sending general Charles Leclerc to Saint-Domingue, but were decisively defeated by the military superiority of the Armée Indigène, though racist historians unwilling to accept this stunning fact claimed it was because of an outbreak of yellow fever.[5] Because of this, the Armée Indigène was now known as the army that freed Saint-Domingue.

Following the French and British model at that time, the Armée Indigène followed a regimental system.

March

When marching for the campaign the troops are usually organized as such: the Chasseurs are in front scouting, followed by the Grenadiers or artillery troops in case of marching against a fort. the Carabiniers which form most of the army are the infantry troops and lastly the Dragoons which are the cavalry troops.

Some famous regiments are:

- 3rd half-brigade under the leadership of Lamartinière, the hero of Crête-à-Pierrot, based in Port-Républicain;

- 4th half-brigade under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the commander-chief, based in St-Marc;

- 9th half-brigade under the leadership of Francois Cappois Lamort, the hero of Vertières, based in Port-de-Paix;

- Dragoons of l'Artibonite under the leadership of Charlotin Marcadieu;

- The Guard of Honor of Toussaint Louverture is composed of 2000 men, including 400 mounted men and music bands.

| Regiment | Commanding officer | Commune | Division | Corps | Troop | Fort |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Toussaint Brave | Fort-Liberté/Lavaxon | Eastern | Infantry | 1500 | St-Joseph |

| 2nd | Christophe Henry | Cap-Hayti | Northern | Infantry | 1500 | Picolet/ Citadelle-Henry/ Bréda |

| 3rd | Gilles Drouet | Port-au-Prince/ Cap-Hayti | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Drouet |

| 4th | Jean-Jacques Dessalines | Dessalines | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Innocent/ Fin-du-Monde/ Doco |

| 5th | Paul Romain | Limbé | Northen | Infantry | 1500 | |

| 6th | Augustin Clerveaux | Dondon | Northern | Infantry | 1500 | |

| 7th | Louis-Gabart | St-Marc | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Diamant/ Béké |

| 8th | Larose | Arcahaie | Northern | Infantry | 1500 | |

| 9th | Francois Lamort Cappois | Port-de-Paix | Northern | Infantry | 1500 | Trois-Rivière |

| 10th | Jean-Philippe Daut | Mirebalais | Eastern | Infantry | 1500 | |

| 11th | Frontiste | Port-au-Prince | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Jacques/ Alexandre |

| 12th | Germain Frère | Port-au-Prince | Western | Infantry | 1500 | National/ Touron |

| 13th | Coco JJ Herne | Cayes | Southern | Infantry | 1500 | Forteresse des Platons |

| 14th | André Vernet | Gonaives | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Bayonnais |

| 15th | Jean-Louis Francois | Aquin | Southern | Infantry | 1500 | Bonnet-Carré |

| 16th | Étienne E. Gérin | Miragoane/ Anse-à-Veau | Southern | Infantry | 1500 | Réfléchit/ Débois |

| 17th | Vancol | Port-Salut | Southern | Infantry | 1500 | |

| 18th | Laurent Férrou | Jérémie | Southern | Infantry | 1500 | Marfranc |

| 19th | Gilles Béneche | Tiburon | Southern | Infantry | 1500 | |

| 20th (Polonais Noir/ Black Polish) | Joseph Jérome | Verettes | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Crête-à-Pierrot |

| 21th | Cangé | Léogane | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Campan |

| 22th | Magloire Ambroise | Jacmel | Southern | Infantry | 1500 | Ogé |

| 24th | Lamarre | Petit-Goave | Western | Infantry | 1500 | Garry |

| Dragoon of the North | Cap-Hayti | Northern | Cavalry | 1000 | ||

| Dragoon of Artibonite | Charlotin Marcadieu | St-Marc | Western | Cavalry | 1000 | |

| Dragoon of the South | Guillaume Lafleur | Cayes | Western | Cavalry | 1000 | |

| Artillery of the North | Cap-Hayti | Northern | Artillery | 1000 | ||

| Artillery of Artibonite | St-Marc | Western | Artillery | 1000 | ||

| Artillery of the South | Cayes | Western | Artillery | 1000 | ||

| Maroon | Sansousi/ Petit-Noel Prieur | Massif du Nord/ Dondon | Northern | Mountain troop | ||

| Maroon | Lamour Dérance | Massif la Selle/ Kenscoff | Southern | Mountain troop | ||

| Maroon | Gilles Bambara | Massif de la Hotte / Goavi | Southern | Mountain troop | ||

Later on, the number of half-brigades went from 29 to 38, with 4 artillery regiments, 86 detached artillery companies, and 64 gendarmerie companies.

Conquest of Haiti

After the troops, regiment, brigade, and demi-brigade have been organized by JJD the troops could now focus and conquering Hayti back from the French.

- André Vernet, Gabart and Dessalines controlled the Artibonite and use it as the base for the operations;

- January 16, 1803, Nicolas Geffrad Sr. and Étienne Gérin with the 13th freed the city of Anse-à-Veau, thus freeing the department of Nippes against the French general Bernard;

- April 12, 1803, Francois Lamort Cappois conquered the city of Port-de-Paix and the island of Tortuga, thus cutting all French supply between Cap-Francais and Mole-St-Nicolas and freeing the department of Haut-Nord-Ouest (department) aiganst the French generals Clauzel and Boscus;

- Larose freed the city of Arcahaie with the 8th, thus freeing the region of Haut-Ouest;

- May 18, 1803, Congress of Arcahaie with Pétion, Gabart, Vernet, Cangé, Larose, and Dessalines on galvanizing the troops of Artibonite and West and vote on the Haitian flag.

- June 30, 1803, Louis Gabart and Dessalines with the 4th, 7th, 20th and 10th freed the city of Mirebalais, thus freeing the department of Centre;

- July 5, 1803, Congress of Camp-Gérrard with Geffrard, Férou, Gérin, Boisrond Tonerre, and Dessalines on galvanizing the troops of Tiburon Peninsula.

- August 4, 1803, Laurent Férou marched toward Jérémie from Cayes through Tiburon with the 18th. One column led by Bazile walked to the city through Marfranc and Férou continued through Abricot thus freeing the department of Grand'Anse;

- September 4, 1803, Louis Gabart and Dessalines conquered the city of St-Marc, thus freeing the department of Bas-Artibonite aiganst the French generals Hénin;

- September 9, 1803, Toussaint Brave and Auguste Clerveaux with 1st, 6th conquered the city of Fort-Liberté, thus freeing the department of North-East against the French general Pamphile de laCroix;

- September 17, 1803, Magloire Ambroise and Cangé with the 21st, 22nd, 23rd conquered the city of Jacmel, thus freeing the department of North-West against the French general Pageot;

- Cangé conquered the city of Léogane with the 21th, 24th thus freeing the department of Ouest-Mériddional;

- Germain Frère and Frontiste of the 11th and 12th controls the area of La Coupe, modern-day Pétionville.

- On there way to siege Port-au-Prince, JJD run Lux and the 5th light out of Croix-des-Bouquets on September 19.

- October 9, 1803, Pétion, Cangé, Gabart and Dessalines with the 3rd, 11th, 12th, 4th, 7th, 20th and 21st marched toward Port-au-Prince. Dessalines established its HQ in Turgeau, Louis Gabart was along rue St-Martin with his troops from the shore to Fort-National, Pétion was on St-Gérard hill with the artillery, and Cangé after taking Fort-Bizoton set up a battery Fort-Mercredi hill thus freeing the department of Ouest against the French general Lavalette;

- October 16, 1803, Geffrard, and Coco Herne conquered the city of Les Cayeswith the 13th and 15th, thus freeing the department of Sud against the French general Brunet;

- Christophe, Clerveaux, Cappoix, Romain and Dessalines gathers a division of 20 000 men from the 2nd, 6th, 8th, 4th, 7th, 3rd, 11th, 14th, 20th, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, the Regiment of Dragoons of Artibonite and an artillery regiment under the command of Zenon freed the city of Cap-Francais. JJD place his HD on habitation Lenormand de Mézy the same place where the Bwakayiman ceremony happened, he sent Paul Romain and Henry Christophe to Vigie through Port-Francais and Cappois, Vernet, and Charlotin to Cape-Heights (Haut-du-Cap) thus on November 19, 1803, freeing the department of Nord against the French general Rochambeau;

- December 4, 1803, Vincent Pourcelly with a battalion of the 9th demi-brigade freed the city of Mole-St-Nicolas, thus freeing the department of Bas-Nord-Ouest chasing the last troops out of Haiti and French general Louis Noailles;

- January 1, 1804, Congress of Gonaives the Independence of Hayti is declared by the Armée Indigéne.

Strategy

The Haitians used their knowledge of the land to wage a full fledge guerilla warfare. Toussaint and Dessalines were inspired by the maroons such as Enriquillo and Boukman and ordered several mountaintop fortresses to be built over each plaine in the mountain ranges of Haiti.

After France and Britain break their peace and declared war on each order, Dessalines capitalized on that concluding a deal with the British Navy, resulting in a blockade of the major bays of the island and seizing any French boat leaving the cities of Haiti to seek refuge elsewhere.

Naval Forces

During the revolutions, Haitians did not have the time nor the need to organize a marine force. Mainly because since the war was declared between France and England again, the Indigène troops only had to force the French troops to admit their capitulation, accord them a cease-fire to gather their troops and French civilians, and the British Navy in the bays would then take them as prisoners.

After the revolution and the establishment of the Haitian State under Dessalines, Christophe, Pétion, Geffrard, and so forth would organize a naval fleet (barge) for defense and cabotage.

Casualties

While the actions of the Armée Indigène were fueled by Enlightenment principles that advocated for the equality of all Frenchmen, the Haitian Revolution had many casualties. Both sides suffered losses from their own violence. The Haitians suffered about 200,000 casualties, while their French opponents suffered tens of thousands of casualties, mostly to yellow fever. Dessalines would later be known for the 1804 massacre of the slave-owning French who did not want to leave Hayti, which lasted for two months.[11]

After the Independence

One of the first decrees of Dessalines after the Independence was to organize the army and their uniforms. The recruitment of young men in the army continued because there was still a threat of French invasion. The constitution of 1805 further organize the army and conscription:

- art 9. No person is worth being a Haitian who is not a good father, a good son, a good husband, and especially a good soldier.

- art 15. The Empire of Hayti is one and indivisible. Its territory is distributed into six military divisions.

- art 16. Each military division shall be commanded by a general of division.

- art 17. These generals of division shall be independent of one another and shall correspond directly with the Emperor or the general in chief appointed by his majesty.

After the assassination of the emperor Jacques 1st, a civil war ensued between the Christophe followers in the north with royalist ambitions and Alexandre S. Pétion and Étienne E. Gérin in the south with republican ambitions. Both factions organize the armed forces similarly with a difference in the names of regiments, uniforms, and colors. Henry 1st organized the troops in 15 regiments with the first three known as the Regiment of the King (Henry 1st), Regiment of the Queen (Marie-Louise Croix-David), and Regiment of the Royal-Prince ( Victor Henry) the rest were simply referred to as the regiment of the communes they are cantoned in such as Regiment of Dondon. He also organized the Royal Navy, Royal Artillery, and Royal Cavalry. The royal's bodyguards are a light cavalry corps. He also had a corps of rural police known as the Royal Daomay which recruited only men at least 6 ft tall.

In the rest of Hayti (West and South), Alexandre Pétion organized the Navy based in Bizoton with gunboats such as Indépendance and le Vengeur. He also organized two other corps: the Presidential Guard and the Guard of the Senate along with military hospitals.

At the reunification of Hayti, under J-P Boyer the Royal bodyguards were incorporated into the Presidential Guards as the Carabiniers à Cheval. Later on, after France officially recognized Haitian Independence, there was no need for such an extensive army, and gradually the troops were reduced to half of its wartime size. President Nicolas Geffrard reduced its size and created an elite corps known as Tirailleurs de la Garde.

By 1915, the army was a shadow of its past glory due to political turmoils, budget cuts, and indiscipline within the ranks. The regimental system is famous for its esprit the corps favors the idolization of the colonel (chief of half-brigades) who in turn use his influence over the troops to execute a coup-d'état. After the US invasion of Haiti, one of the first decrees put an end to the Indigène Army and disarm the civil population. Although Charlemagne Péralte, commander of Léogane refuses to be a witness of this act against the sovereignty of Haiti. He organized and led the Cacos.

Legacy

The actions of the Armée Indigène in the Haitian Revolution would serve as inspiration to the slaves in the United States. Haiti was finally recognized by France in 1825, and later by the United States, in 1862.[5] South American leader Simon Bolivar and Miranda traveled to Hayti looking for military support for the Liberation of Grand-Colombia.

In Lakoun Souvnans a Vodoun community in Gonaives, Artibonite, which keeps a Dawonmen Wayal (Royal Dahomean: EN) categories there loas or Vodoun deities in classification similar to the Indigène troops, some loas are:

This rich military history made Haiti a very martial country; this influence can be seen in multiple aspects of Haitian culture. Rara, a popular musical style in Haiti known as Gàgà in the Dominican Republic is a testament to that.

Until 1915, every Haytian head-of-state outside Michel Oreste was a military man.

Fortification

After the Independence of Hayti, the Haitians were preparing for an eventual return of French troops, and Dessalines decide to reorganize the country. The basic of administrative division of the country went from parish to military garrison and department to military division. The Empire of Hayiti had six military divisions each administratively autonomous from each under the general guidance of Jacques 1st, resulting in a quasi-federalism.

The emperor then ordered all division-general to build forts and docos in the mountains controlling all the major plains, bays, and all interior roads. Nowadays, most forts are still in place although they are not used for military purposes the most famous are:

- Citadelle Henry over the city of Cap-Haitian and the northern plains

- Fortification of Dessalines, the capital of the empire, designed by Alexandre Pétion overlooking the Artibonite Valley

- Twin forts Jacques and Alexandre over the city of Port-au-Prince and the Cul-de-Sac plaine

- Platon Citadelle over the city of Les Cayes and the Cayes plaine

List of generals

Commanders-in-chief

- Toussaint Louverture, Commander-in-chief (1793-180, governor-general of Saint-Domingue 1801–1803)

- Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Commander-in-chief (1803-1804, first president and later emperor of Haiti)

Division generals

- Henry Christophe, commander of Dondon and the 1st division of North region

- Alexandre Pétion, commander of Arcahaie and the 2nd division of West region

- Augustin Clervaux, commander of Marmelade and the 2nd division of North region

- Nicolas Geffrard, and the 1st division of South region

- Andre Vernet, commander of Gonaives and the 1st division of West region

- Louis Gabart, commander of St-Marc and the Artibonite region

Brigadier-generals

- Paul Romain, commander of Limbé

- Étienne Élie Gerin, commander of Anse-à-Veau

- François Capois, commander of Port-de-Paix

- Jean-Philippe Daut

- Jean-Louis François, commander of Aquin

- Laurent Férou, commander of Jérémie

- Pierre Cangé, commander of Léogane

- Laurent Bazelais

- Magloire Ambroise, commander of Jacmel

- J. J. Herne, commander of Les Cayes

- Toussaint-Brave, commander of Fort-Liberté

- Yayou, commander of Grande Riv du Nord

Other generals

- Jacques Maurepas

- Jean-François Papillon

- Georges Biassou

- Jeannot Bullet

- Louis Michel Pierrot

- Hyacinthe Moïse

- Joseph Balthazar Inginac

- Charlotin Marcadieu Chief of Cavalry

Adjutants-general

- Guy-Joseph Bonnet

- Chevalier

- Marion

- Morelly

- Papalier

Officers

- Nicolas Pierre Mallet

References

- Lawless, Robert, and James A. Ferguson. "Haiti". Encyclopædia Britannica. February 7, 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Fombrun, Odette Roy. "History of the Haitian Flag of Independence". Flag Heritage Foundation.org. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Rodriguez, J. P. "Tacky's Rebellion (1760–1761)". The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery. 1. A - K. 1997. ABC-CLIO. p.229 ISBN 978-0-87436-885-7

- Jackson, Maurice, and Jacqueline Bacon. African Americans and the Haitian revolution selected essays and historical documents. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- "Haitian Revolution". Encyclopædia Britannica. December 28, 2017. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- McPhee, Peter. Liberty or Death. S.l.: Yale Univ Press, 2017.

- "Case Study 1: St. Domingue - Vincent Oge & Toussaint l'Ouverture". Case Study 1: St. Domingue - Vincent Oge & Toussaint l'Ouverture: The Abolition of Slavery Project. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Shen, Kona. "Haitian Revolution Begins August–September 1791". The Haitian Revolution 1791. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Steward, T. G. The Haitian revolution, 1791 to 1804; or, Side lights on the French Revolution. New York: Russell & Russell, 1971

- Fagg, John E. "Toussaint Louverture". Encyclopædia Britannica. December 18, 2017. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- Popkin, Jeremy D. (2007). Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection. University of Chicago Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-226-67582-4.

External links

(Picture of Dessalines is named Huyes del valor frances, pero matando blancos, by Manuel Lopes Lopez Iodibo. It is an engraving in the book Vida de J.J. Dessalines, gefe de los negros de Santo Domingo and is located in the John Carter Brown Library)

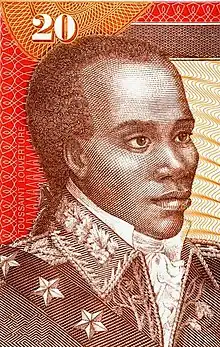

(Picture of Toussaint Louverture is named Le général Toussaint Louverture. The artist is unknown, and it is currently in the New York Public Library)