Mississippi Alluvial Plain (ecoregion)

The Mississippi Alluvial Plain is a Level III ecoregion designated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in seven U.S. states, though predominantly in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. It parallels the Mississippi River from the Midwestern United States to the Gulf of Mexico.

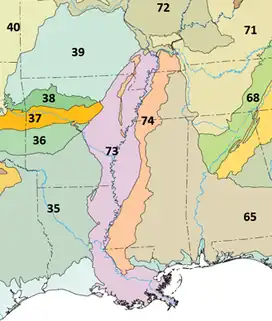

| Mississippi Alluvial Plain ecoregion | |

|---|---|

Level III ecoregions in the region, with the Mississippi Alluvial Plain ecoregion marked as (73) (full map) | |

| Ecology | |

| Borders | List

|

| Geography | |

| Area | 44,834 km2 (17,311 sq mi) |

| Country | United States |

| States |

|

| Climate type | Humid subtropical (Cfa) |

The Mississippi Alluvial Plain ecoregion has been subdivided into fifteen Level IV ecoregions.[1]

Description

The Mississippi Alluvial Plain extends along the Mississippi River from the confluence of the Ohio River and Mississippi River southward to the Gulf of Mexico; temperatures and annual average precipitation increase toward the south. It is a broad, nearly level, agriculturally-dominated alluvial plain. It is veneered by Quaternary alluvium, loess, glacial outwash, and lacustrine deposits. River terraces, Swales, and levees provide limited relief, but overall, it is flatter than neighboring ecoregions in Arkansas, including the South Central Plains. Nearly flat, clayey, poorly-drained soils are widespread and characteristic. Streams and rivers have very low gradients and fine-grained substrates. Many reaches have ill-defined stream channels.

The ecoregion provides important habitat for fish and wildlife, and includes the largest continuous system of wetlands in North America. It is also a major bird migration corridor used in fall and spring migrations, known as the Mississippi Flyway. Potential natural vegetation is largely southern floodplain forest and is unlike the oak–hickory and oak–hickory–pine forests that dominate uplands to the west in Ecoregions 35, 36, 37, 38, and 39; loblolly pine, so common in the South Central Plains (35), is not native to most forests in the Arkansas portion of Ecoregion 73. The Mississippi Alluvial Plain has been widely cleared and drained for cultivation; this widespread loss or degradation of forest and wetland habitat has impacted wildlife and reduced bird populations. Presently, most of the northern and central sections are in cropland and receive heavy treatments of insecticides and herbicides; soybeans, cotton, and rice are the major crops, and aquaculture is also important.

Agricultural runoff containing fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and livestock waste have degraded surficial water quality. Concentrations of total suspended solids, total dissolved solids, total phosphorus, ammonia nitrogen, sulfates, turbidity, biological oxygen demand, chlorophyll a, and fecal coliform are high in the rivers, streams, and ditches of the region; they are often much greater than elsewhere in Arkansas, increase with increasing watershed size, and are greatest during the spring, high-flow season. Fish communities in least altered streams typically have an insignificant proportion of sensitive species; sunfishes are dominant followed by minnows. Man-made flood control levees typically flank the Mississippi River and, in effect, separate the river and its adjoining habitat from the remainder of its natural hydrologic system; in so doing, they interfere with sediment transfer within the region and have reduced available habitat for many species. Between the levees that parallel the Mississippi River is a corridor known as the batture lands. Batture lands are hydrologically linked to the Mississippi River, flood-prone, and contain remnant habitat for “big river” species (e.g., pallid sturgeon) as well as river-front plant communities; they are too narrow to map as a separate Level IV ecoregion. Earthquakes in the early nineteenth century offset river courses in Ecoregion 73. Small to medium size earthquakes still occur frequently; their shocks are magnified by the alluvial plain's unconsolidated deposits, creating regional land management issues.

Level IV ecoregions

Northern Holocene Meander Belts (73a)

The Northern Holocene Meander Belts ecoregion is a flat to nearly flat floodplain containing the meander belts of the present and past courses of the Mississippi River. Point bars, natural levees, swales, and abandoned channels marked by meander scars and oxbow lakes are common and characteristic. Ecoregion 73a tends to be slightly lower in elevation than adjacent ecoregions. Its abandoned channel network is more extensive than in the Southern Holocene Meander Belts (73k) of Louisiana. Ecoregion 73a is underlain by Holocene alluvium; it lacks the Pleistocene glacial outwash deposits of Ecoregion 73b. Soils on natural levees are relatively coarse-textured, well-drained, and higher than those on levee back slopes and point bars; they grade to very heavy, poorly-drained clays in abandoned channels and swales. Overall, soils are not as sandy as the Northern Pleistocene Valley Trains (73b) and are finer and have more organic matter than the Arkansas/Ouachita River Holocene Meander Belts (73h). Natural vegetation varies with site characteristics. Younger sandy soils have fewer oaks and more sugarberry, elm, ash, pecan, cottonwood, and sycamore than Ecoregion 73d. Widespread draining of wetlands and removal of bottomland forests for cropland has occurred. Soybeans, cotton, corn, sorghum, wheat, and rice are the main crops. Catfish farms are increasingly common and contribute to the already large agricultural base. The ecoregion covers 2,635 square miles (6,820 km2).[2]

Protected areas include Choctaw Island Wildlife Management Area (WMA), Lake Chicot State Park (SP), and Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in Arkansas, Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge in Louisiana, Big Oak Tree SP in Missouri, Chickasaw NWR, Lake Isom NWR, T.O. Fuller SP, and Reelfoot Lake SP in Tennessee, and Reelfoot NWR in Tennessee and Kentucky. In Mississippi, the ecoregion is protected in the following areas: Dahomey NWR, Delta National Forest and Hillside NWR, Leroy Percy SP, Mathews Brake NWR, Morgan Brake NWR, Panther Swamp NWR, and the Yazoo NWR.

The area also includes four culturally important sites: Fort Defiance in Illinois, Columbus-Belmont State Park in Kentucky, Winterville Mounds in Mississippi and Towosahgy State Historic Site in Missouri.

Northern Pleistocene Valley Trains (73b)

The Northern Pleistocene Valley Trains ecoregion is a flat to irregular alluvial plain composed of sandy to gravelly glacial outwash overlain by alluvium; sand sheets, widespread in the St. Francis Lowlands (73c), are absent. The Pleistocene outwash deposits of Ecoregion 73b are usually coarser and better drained than the alluvial deposits of Ecoregions 73a, 73d, and 73f. They were transported to Arkansas by the Mississippi River and its tributaries and have been subsequently eroded, reduced in size, and fragmented by laterally migrating channels or buried by thick sediments. Ecoregion 73b has little local relief or stream incision. Elevations tend to be slightly higher than adjacent parts of Ecoregions 73a and 73d. Cropland is extensive and has largely replaced the original forests; soybeans are the main crop and cotton is also produced. The few remaining forests are dominated by species typical of higher bottomlands such as Nuttall oak, willow oak, swamp chestnut oak, sugarberry, and green ash. There are more lowland oaks in Ecoregion 73b than in Ecoregions 73a and 73d. The ecoregion covers 1,418 square miles (3,670 km2) within Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee, with 78% in Mississippi, and the remainder roughly split between the remaining two states.[2]

Protected areas within the region include the Tallahatchie NWR in Mississippi.

St. Francis Lowlands (73c)

The St. Francis Lowlands ecoregion is flat to irregular and has many relict channels. Ecoregion 73c is mainly composed of late-Wisconsinan age glacial outwash deposits and, in contrast to Ecoregion 73b, is partly covered by undulating sand sheets. Sand blows and sunk lands occur and have been attributed to the 1811–12 New Madrid earthquakes. Loess, which veneers older outwash deposits in Ecoregion 73g, is absent. Topography, lithology, and hydrology vary over short distances and natural vegetation varies with site characteristics. Cropland is extensive and has largely replaced the original forests; soybeans, corn, and cotton are the most common crops but wheat, sorghum, and rice are also produced. Although the streams of the St. Francis Lowlands have been extensively channelized, water quality tends to be better than in the less channelized areas of Ecoregion 73g because of a lack of loess veneer in Ecoregion 73c. The ecoregion covers 3,486 square miles (9,030 km2) within Arkansas and Missouri, with 64% in Missouri.[2]

The lands immediately adjacent to the St. Francis River are preserved in the St. Francis Sunken Lands WMA in Arkansas. The Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge preserves flat flooded swamplands created by the New Madrid earthquakes.

Northern Backswamps (73d)

The Northern Backswamps ecoregion is made up of low-lying overflow areas on floodplains, and includes poorly drained flats and swales. Water often collects in its marshes, swamps, oxbow lakes, ponds, and low gradient streams. Soils developed from clayey alluvium including overbank and slack-water deposits; they commonly have a high shrink-swell potential and are locally rich in organic material. Water levels are seasonally variable. Native vegetation in the wettest areas is generally dominated by bald cypress–water tupelo forest; slightly higher and better drained sites have overcup oak–water hickory forest and the highest, best-drained areas support Nuttall oak forest. Today, bottomland forest, cropland, farmed wetlands, pastureland, and catfish farms occur. Backswamps are important areas for capturing excess nutrients from local waters and for storing water during heavy rain events. The ecoregion covers 1,821 square miles (4,720 km2) within Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, with 54% in Mississippi, 35% in Louisiana, and the balance in Arkansas.[2]

Grand Prairie (73e)

The Grand Prairie ecoregion is a broad, loess-covered terrace formerly dominated by tall grass prairie and now primarily used as cropland. It is typically almost level. However, incised perennial and intermittent streams occur and a narrow belt of low hills is found in the east. Prior to the 19th century, flatter areas with slowly to very slowly permeable soils (often containing fragipans) supported Arkansas's largest prairie. They were generally bounded by open woodland or savanna. In all, about 400,000 acres of prairie grasses and forbs occurred in Ecoregion 73e, and were a sharp contrast to the bottomland forests that once dominated other parts of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain (73). Low hills were covered by upland deciduous forest containing white oak, black oak and southern red oak. Drier ridges were dominated by post oak. Narrow floodplains had bottomland hardwood forests. Cropland has now largely replaced the native vegetation. In the process, some prairie species have been extirpated from the ecoregion (e.g., greater prairie chicken); others have been sharply reduced in population and restricted to a few prairie remnants. Distinctively, rice is the main crop; soybeans, cotton, corn, and wheat are also grown. Rice fields provide habitat and forage for large numbers and many species of waterfowl; duck and goose hunting occurs. The ecoregion covers 1,939 square miles (5,020 km2), entirely within Arkansas.[2]

Western Lowlands Holocene Meander Belts (73f)

The Western Lowlands Holocene Meander Belts ecoregion is a flat to nearly flat floodplain containing the meander belts of the present and past courses of the White River, Black River, and Cache River. Its meander belts are narrower than the Northern Holocene Meander Belts (73a), but point bars, natural levees, swales, and abandoned channels are common in both regions. Soils on natural levees are relatively coarse-textured, well-drained, and higher than those on levee back slopes and point bars; they grade to heavy, poorly-drained clays in abandoned channels and swales. Natural vegetation varies with site characteristics. Today, Ecoregion 73f contains some of the most extensive remaining tracts of native bottomland hardwood forest in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. Cropland also occurs. Flood control levees are less developed and riverine processes are more natural and dynamic than in Ecoregion 73a. Backwater flooding in the White River occurs well upstream of its confluence with the higher Mississippi River; as a result, riparian and natural levee communities are less common and oak-dominated communities are more widespread than in Ecoregion 73a. Wetlands in the Cache-lower White River systems have been designated as one of only nineteen “Wetlands of International Importance” in the United States by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Regulation of White River flow, in combination with the downcutting of the Mississippi River for navigation (and related wing levees and cutoffs), have altered flood regimes on the lower White River, thereby increasing stream bank instability and bottomland forest mortality in Ecoregion 73f. Most streams and rivers in Ecoregion 73f are fed by the Ozark Highlands and Boston Mountains; sediment load is generally less than in the Mississippi River. The ecoregion covers 1,316 square miles (3,410 km2), with 99% within Arkansas.[2]

Western Lowlands Pleistocene Valley Trains (73g)

The terraces of the Western Lowlands Pleistocene Valley Trains are largely composed of Pleistocene glacial outwash that was transported to Arkansas by the Mississippi River and deposited by braided streams. Physiography is widely muted by windblown silt deposits (loess), sand sheets, or sand dunes; loess and sand sheets are more widespread than in the Northern Pleistocene Valley Trains (73b) and St. Francis Lowlands (73c). Many interdunal depressions called “sandponds” occur and are either in contact with the water table or have a perched aquifer. Elevations are higher than adjacent parts of the Northern Holocene Meander Belts (73a) and Western Lowlands Holocene Meander Belts (73f); consequently, uplands are rarely if ever flooded. Native plant communities are different from more frequently inundated ecoregions; for example, post oak and loblolly pine are native to Ecoregion 73g but are absent from lower, overflow areas. Sandpond forest communities are generally dominated by overcup oak, water hickory, willow oak, and pin oak; understory in a few sandponds may include pondberry (Lindera melissifolia), federally listed as endangered. Today, cropland is extensive and the main crops are soybeans and cotton. Commercial crawfish, baitfish, and catfish farms are common. The Western Lowlands Pleistocene Valley Trains (73g) ecoregion is a wintering ground for water fowl. Duck hunting is widespread. The ecoregion covers 1,316 square miles (3,410 km2) between Arkansas and Missouri, with 86% in Arkansas.[2]

Arkansas/Ouachita River Holocene Meander Belts (73h)

The Arkansas/Ouachita River Holocene Meander Belts ecoregion is a flat to nearly flat floodplain containing the meander belts of the present and past courses of the lower Arkansas River and Ouachita Rivers. Point bars, natural levees, swales, and abandoned channels marked by meander scars and oxbow lakes are common and characteristic. Soils on natural levees are more coarse-textured, well-drained, and higher than those on levee back slopes and point bars. Soils grade to poorly-drained clays in abandoned channels and swales. Overall, soils have less organic matter than in the Northern Holocene Meander Belts (73a). Bayou Bartholomew inhabits the longest section of abandoned channels. It flows against the edge of the South Central Plains, receives drainage from it, and has sufficient habitat diversity to be one of the most species-rich streams in North America. Bayou Bartholomew supports over half of all known mussel species found in Louisiana. Within an abandoned course, bald cypress and/or water tupelo typically grow in the modern stream channel adjacent to a strip of wet bottomland hardwood forest dominated by overcup oak and water hickory. The remainder of the native forest has largely been cleared and drained for cropland and pastureland. Corn, cotton, and soybeans are the main crops.

Arkansas/Ouachita River Backswamps (73i)

The flats, swales, and natural levees of the Arkansas/Ouachita River Backswamps ecoregion include the slackwater areas along the Arkansas and Ouachita rivers, where water often collects into swamps, oxbow lakes, ponds, and sloughs. In contrast to the Northern Backswamps (73d), this region is widely veneered with natural levee deposits. Soils derived from these deposits are Alfisols, Vertisols, and Inceptisols that are generally more loamy and better drained than the clayey soils of the Northern Backswamps (73d). As a result, willow oak and water oak are native instead of other species adapted to wetter overflow conditions. Drainage canals and ditches are common. This artificial drainage and the sandy veneer of natural levee deposits help explain why Ecoregion 73i is more easily and widely farmed than the Northern Backswamps (73d). Soybeans, corn, cotton, and rice are important crops but forests and forested wetlands also occur.

Macon Ridge (73j)

Macon Ridge is underlain almost entirely by Pleistocene glacial outwash deposits that were transported to Arkansas by the Mississippi River and deposited by braided streams. It is veneered by windblown silt deposits (i.e. loess) like Ecoregions 73e, 73g, and 74a. Soils are influenced by loess and contrast with the alluvial soils of Ecoregions 73a and 73h. Macon Ridge (73j) is a continuation of the Western Lowlands Pleistocene Valley Trains (73g) but is better drained, and supports drier plant communities. Its eastern edge is 20 to 30 feet above the adjacent, lithologically and physiographically distinct, Northern Holocene Meander Belts (73a). The western side of Macon Ridge (73j) is lower than the eastern side, and is about the same elevation as the lithologically and physiographically distinct Arkansas/Ouachita River Holocene Meander Belts (73h). Native forest types range from those of better drained bottomlands dominated by willow oak, water oak, and swamp chestnut oak to upland hardwood forests dominated by white oak, southern red oak, and post oak. Prairies and loblolly pinedominated areas may also have occurred on Macon Ridge (73j). Today, Ecoregion 73j is a mosaic of pastureland, forest, and cropland. Soybeans, cotton, and oats are major crops. The ecoregion covers 1,735 square miles (4,490 km2) between Arkansas and Louisiana, with 86% within Louisiana.[2]

In Arkansas, most of Macon Ridge is within Chicot County between Lake Village and Eudora.[2]

Southern Holocene Meander Belts (73k)

The Southern Holocene Meander Belts ecoregion stretches from just north of Natchez, Mississippi south to New Orleans, Louisiana. Similar to the Northern Holocene Meander Belts (73a), point bars, oxbows, natural levees, and abandoned channels occur. This region, however, has a longer growing season, warmer annual temperatures, some hyperthermic soils, and more precipitation than its northern counterparts of 73a and 73h. Soils are somewhat poorly and poorly drained Inceptisols, Entisols, and Vertisols. The ecoregion contains minor species such as live oak, laurel oak, and Spanish moss that are generally not found in the more northerly regions. The bottomland forests have been cleared and the region has been extensively modified for agriculture, flood control, and navigation. The levee system is extensive throughout the region. Soybeans, sugarcane, cotton, corn, and pasture are the major crops, with crawfish aquaculture common. The ecoregion covers 3,305 square miles (8,560 km2), almost entirely within Louisiana.[2]

Southern Pleistocene Valley Trains (73l)

The Southern Pleistocene Valley Trains ecoregion is a continuation of the northern valley train regions in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee. It is composed of scattered small remnants of early-Wisconsin glacial outwash deposits, similar to those of Macon Ridge (73j). This ecoregion, however, has warmer annual temperatures, a longer growing season, and higher annual rainfall. Soils are somewhat poorly and poorly drained Alfisols, Inceptisols, and Vertisols with loamy and clayey surfaces. Some species occur here that are not present in the Macon Ridge (73j) or Western Lowlands Pleistocene Valley Trains (73g) ecoregions to the north in Arkansas. Overcup oak, Nuttall oak, honey locust, elm, water oak, sweetgum, blackgum, and hickory are the most common tree species. This region is generally higher than the adjacent Southern Backswamps (73m) ecoregion and soils are more sandy and better drained than the heavy clay soils of the backswamps. Cropland and pasture is common with corn, soybeans, and cotton as major crops. The ecoregion covers 195 square miles (510 km2), entirely within Louisiana.[2]

Southern Backswamps (73m)

The Southern Backswamps ecoregion is generally warmer, has a longer frost free period, and has more precipitation than the Northern Backswamps (73d). Similar to 73d, soils are mostly poorly drained, clayey Vertisols, rich in organic matter. Wetlands are common and flooding occurs frequently. Bottomland hardwood forests are more prevalent in this region than in the adjacent Southern Holocene Meander Belts (73k), where cropland is common. Channelization and flood control systems have modified this region and impacted many of the wetland habitats. The ecoregion covers 1,722 square miles (4,460 km2), almost entirely within Louisiana.[2]

Inland Swamps (73n)

The Inland Swamps ecoregion marks a transition, ranging from the fresh waters of the Southern Backswamps (73m) at the northern extent of the intratidal basins to the fresh, brackish, and saline waters of the deltaic marshes of Ecoregion 73o. It includes a large portion of the Atchafalaya Basin. Soils are mostly poorly or very poorly drained, clayey Entisols and Vertisols. Swamp forest communities are dominated by bald cypress and water tupelo, which are generally intolerant of brackish water except for short periods. In areas where freshwater flooding is more prolonged, the vegetative community is dominated by grasses, sedges, and rushes. This region contains one of the largest bottomland hardwood forest swamps in North America. Deposits include organic clays and peats up to 20 feet (6.1 m) thick, and inter-bedded fresh- and brackish-water carbonaceous clays. The levees in place on either side of the Mississippi River have diverted much of the river flow from its natural tendency to flow into the Atchafalaya Basin. Large concrete structures prevent diversion into the Atchafalaya River, and flow from the Red River is also controlled. While this helps control flooding, it has also modified the region and contributed to the loss of wetland habitat. The ecoregion covers 3,051 square miles (7,900 km2), entirely within Louisiana.[2]

Deltaic Coastal Marshes and Barrier Islands (73o)

Brackish and saline marshes dominate the Deltaic Coastal Marshes and Barrier Islands ecoregion. The region supports vegetation tolerant of brackish or saline water including saltmarsh cordgrass, marshhay cordgrass, black needlerush, and coastal saltgrass. Black mangrove occurs in a few areas, and some live oak is found on Grand Isle and along old natural levees. Extensive organic deposits lie mainly below sea level in permanently flooded settings resulting in the development of mucky surfaced Histosols. Sediments of silts, clays, and peats contain large amounts of methane, oil, and hydrogen sulfide gas. Inorganic sediments found within the ecoregion are soft and have high water contents. They will shrink dramatically upon draining. The wetlands and marshes act as a buffer to help moderate flooding and tidal inundation during storm events. Lack of sediment input, delta erosion, land subsidence, and rising sea levels threaten the region. The ecoregion covers 5,298 square miles (13,720 km2), entirely within Louisiana.[2]

See also

- Ecoregions defined by the EPA and the Commission for Environmental Cooperation:

- List of ecoregions in North America (CEC)

- List of ecoregions in the United States (EPA)

- List of ecoregions in Arkansas

- List of ecoregions in Louisiana

- List of ecoregions in Mississippi

- The conservation group World Wildlife Fund maintains an alternate classification system:

References

-

This article incorporates public domain material from Woods, A.J., Foti, T.L., Chapman, S.S., Omernik, J.M.; et al. Ecoregions of Arkansas (PDF). United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from Woods, A.J., Foti, T.L., Chapman, S.S., Omernik, J.M.; et al. Ecoregions of Arkansas (PDF). United States Geological Survey.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs). -

This article incorporates public domain material from US Level IV Ecoregions shapefile with state boundaries (SHP file). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from US Level IV Ecoregions shapefile with state boundaries (SHP file). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

This article incorporates public domain material from Daigle, JJ; Griffith, GE; Omernik, JM; Faulkner, PL; et al. Ecoregions of Louisiana (PDF). United States Geological Survey. (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs).

This article incorporates public domain material from Daigle, JJ; Griffith, GE; Omernik, JM; Faulkner, PL; et al. Ecoregions of Louisiana (PDF). United States Geological Survey. (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs).