Cisplatine War

The Cisplatine War (Portuguese: Guerra Cisplatina), also known as the Argentine-Brazilian War (Spanish: Guerra argentino-brasileña) or, in Argentine and Uruguayan historiography, as the Brazil War (Guerra del Brasil), the War against the Empire of Brazil (Guerra contra el Imperio del Brasil)[7] or the Liberating Crusade (Cruzada Libertadora) in Uruguay, was an armed conflict in the 1820s between the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata and the Empire of Brazil over Brazil's Cisplatina province, in the aftermath of the United Provinces' and Brazil's independence from Spain and Portugal. It resulted in the independence of Cisplatina as the Oriental Republic of Uruguay.

| Cisplatine War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

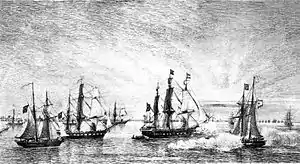

From top left: Battle of Juncal, Battle of Sarandí, Oath of the Thirty-Three Orientals, Battle of Monte Santiago, Battle of Quilmes, Battle of Ituzaingó | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

1826:[3] 6,832 regulars 1828:[4] 15,000 |

1826:[5] ~12,000 regulars & militia 1828:[6] 6,000 | ||||||||

Background

Led by José Gervasio Artigas, the region known as the Banda Oriental, in the Río de la Plata Basin, revolted against Spanish rule in 1811, against the backdrop of the 1810 May Revolution in Buenos Aires as well as the regional rebellions that followed in response to Buenos Aires' pretense of primacy over other regions in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. In the same context, the Portuguese Empire, then headquartered in Rio de Janeiro, took measures to solidify its hold on Rio Grande do Sul and to annex the region of the former Eastern Jesuit Missions.

From 1814 on, the Provincia Oriental, led by Artigas, joined forces with the provinces of Santa Fe and Entre Rios in a loose confederation called the Federal League, which resisted Buenos Aires' authority. After a series of banditry incidents in the territory which was previously claimed by the Portuguese Empire, in what is today the state of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, the now United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves invaded the Banda Oriental in 1816.

Artigas was finally defeated by the Luso-Brazilian troops in 1820 at the Battle of Tacuarembó.[8] The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves then formally annexed the Banda Oriental as a province of the Kingdom of Brazil, under the name Cisplatina, with support from local elites. With the annexation, the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves now enjoyed strategic access to the Río de la Plata and control of the estuary's main port, the city of Montevideo.

After Brazilian independence, in 1822, Cisplatina remained as a province of the newly formed Empire of Brazil. It sent two delegates to the 1823 Constituent Assembly that was tasked with drafting Brazil's first constitution.[9] The constitution drafted by the Assembly was rejected by Emperor Pedro I, who dissolved the Assembly and issued a constitution himself in 1824.[10] Under the 1824 Constitution, the Cisplatina province enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy, more so than other provinces within the Empire.[11]

Conflict

While initially supporting the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves' intervention in the Banda Oriental, the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata later urged the local populace to rise up against Brazilian authority, covertly giving them political and material support aiming to establish sovereignty over the region.

Rebels led by Fructuoso Rivera and Juan Antonio Lavalleja carried on resistance against Brazilian rule. On 25 August 1825, an assembly of delegates from all over the Banda Oriental met in Florida and declared its independence from Brazil, while also declaring, at the same time, its allegiance to the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata.[12] On 25 October 1825 the congress of the United Provinces declared the annexation of the Banda Oriental. In response, Brazil declared war on the United Provinces on 10 December 1825.[13]

The two navies which confronted each other in the Río de la Plata and the South Atlantic were in many ways opposites. The Empire of Brazil was a major naval power with 96 warships, large and small, an extensive coastal trade and a large international trade carried on mostly in British, French and American ships. The United Provinces had similar international trading links but had few naval pretensions. Its navy consisted of only half a dozen warships and a few gunboats for port defence. Both navies were short of indigenous sailors and relied heavily on British—and, to a lesser extent—American and French officers and sailors, the most notable of which were the Irish born admiral William Brown, and the commander of the Brazilian inshore squadron, the English commodore James Norton.[14]

The strategy of the two nations reflected their respective positions. The Brazilians immediately imposed a blockade on the Río de la Plata and the trade of Buenos Aires on 31 December 1825,[13] while the Argentines attempted to defy the blockade using Brown's squadron while unleashing a swarm of privateers to attack Brazilian seaborne commerce in the South Atlantic from their bases at Ensenada and more distant Carmen de Patagones.[15] The Argentines gained some notable successes—most notably by defeating the Brazilian flotilla on the Uruguay River at the Battle of Juncal and by beating off a Brazilian attack on Carmen de Patagones. But by 1828, the superior numbers of Brazil's blockading squadrons had effectively destroyed Brown's naval force at the Monte Santiago and was successfully strangling the trade of Buenos Aires and the government revenue it generated.[16]

On land, the Argentine army initially crossed the Río de la Plata and established its headquarters near the town of Durazno. General Carlos María de Alvear invaded Brazilian territory and a series of skirmishes followed. Emperor Pedro I planned a counteroffensive by late 1826, and managed to gather a small army mainly composed of southern Brazilian volunteers and European mercenaries. The recruiting effort was hampered by local rebellions throughout Brazil, which forced the Emperor to relinquish direct command of his Army, return to Rio de Janeiro and bestow command of the troops on Felisberto Caldeira Brant, Marquis of Barbacena. The Brazilian counteroffensive was eventually stopped at the Battle of Ituzaingó.

Ituzaingó was the only battle of some magnitude in the whole war. A series of smaller clashes ensued, including the Battle of Sarandí, and the naval Battles of Juncal and Monte Santiago. Scarcity of volunteers severely hampered the Brazilian response, and by 1828 the war effort had become extremely burdensome and increasingly unpopular in Brazil. That year, Rivera reconquered the territory of the former Eastern Jesuit Missions.

Aftermath

The stalemate in the Cisplatine War was caused by the inability of the Argentine and Uruguayan land forces to capture major cities in Uruguay and Brazil,[17] the severe economic consequences imposed by the Brazilian blockade of Buenos Aires,[18] and the lack of manpower for a full-scale Brazilian land offensive against Argentine forces. There was also increasing public pressure in Brazil to end the war. All of this motivated the interest on both sides for a peaceful solution.

Given the high cost of the war for both sides and the threat it posed to trade between the United Provinces and the United Kingdom, the latter pressed the two belligerent parties to engage in peace negotiations in Rio de Janeiro. Under British and French mediation, the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata and the Empire of Brazil signed the 1828 Treaty of Montevideo, which acknowledged the independence of the Cisplatina under the name Eastern Republic of Uruguay.

The treaty also granted Brazil sovereignty over the eastern section of the former Eastern Jesuit Missions and, most importantly, guaranteed free navigation of the Río de la Plata, a central national security issue for the Brazilians.

In Brazil, the loss of Cisplatina added to growing discontent with Emperor Pedro I. Although it was far from the main reason, it was a factor that led to his abdication in 1831.

Legacy

Although the war was not a war of independence, as none of the belligerents fought to establish an independent nation, it has a similar recognition within Uruguay. The Thirty-Three Orientals are acknowledged as national heroes, who freed Uruguay from Brazilian rule. The landing of the Thirty-Three Orientals is also known as the "Liberation crusade".[19]

The war has a similar reception within Argentina, considered as a brave fight against an enemy of superior forces. The Argentine Navy has named many ships after people, events and ships involved in the war. William Brown (known as "Guillermo Brown" in Argentina) is considered the father of the Argentine navy,[20][21][22][23] and is treated akin to an epic hero for his actions in the war. He is also known as the "Nelson of the Río de la Plata".[24]

Brazil has had little interest in the war beyond naval warfare buffs. Few Brazilian historians have examined it in detail. The national heroes of Brazil are instead from Brazilian independence, the conflicts with Rosas (Platine War) or the Paraguayan War.[25]

Despite the role of Britain in the war, and the presence of British naval officials on both sides of the conflict, the war is largely unknown in the English-speaking world.[25]

See also

References

Notes

- Articles I and II of the Preliminary Peace Convention:[1]

- Article I: "His Majesty, the Emperor of Brazil, declares the Province of Montevideo, today called Cisplatina, separated from the territory of the Empire of Brazil, so that it can constitute itself in a free State, and independent of all and any nation, under the form of government that it deems most suited to its interests, needs and resources."

- Article II: "The government of the Republic of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata agrees to declare, for its part, the independence of the Province of Montevideo, today called Cisplatina, and that it constitutes a free and independent State in the terms declared in the preceding article."

Citations

- Câmara dos Deputados 1828, p. 121.

- Castellanos, La Cisplatina, la Independencia y la república caudillesca, pág. 73–77.

- Barroso 2019, p. 124.

- Carneiro 1946, pp. 170–171.

- Barroso 2019, p. 121.

- Carneiro 1946, p. 170.

- Juan Beverina (1927). La guerra contra el Imperio del Brasil (in Spanish). Biblioteca del Oficial, Bs. As.

- Garcia 2012, p. 75.

- Calmon 2002, p. 192.

- Lustosa 2007, pp. 135–136.

- Manning 1918, p. 295.

- Bento 2003, p. 23.

- Bento 2003, p. 24.

- Vale 2000, pp. 13–28.

- Vale 2000, pp. 69–116.

- Vale 2000, pp. 135–206.

- SCHEINA, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: the age of the caudillo, 1791–1899, Brassey's, 2003.

- "The economic effects of the blockade" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- Uruguay educa Archived 2011-12-03 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Spanish: El padre de la Armada Argentina. Used mainly in Argentina but also in other countries like the United Kingdom, see e.g. this BBC report. URL accessed on October 15, 2006.

- Spanish: Guillermo Brown or Almirante Brown, see e.g. his biography at Planeta Sedna. URL accessed on October 15, 2006.

- Irish: Béal Easa, see report at County Mayo's official website. URL accessed on October 15, 2006.

- Irish: Contae Mhaigh Eo, according to its official website. Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed on October 15, 2006.

- Vale 2000, p. 297.

- Vale 2000, p. 298.

In English

- Manning, William R. (1918). "An Early Diplomatic Controversy Between the United States and Brazil". The American Journal of International Law. 12 (2): 291–311. doi:10.2307/2188145. JSTOR 2188145. S2CID 147296231.

- McBeth, Michael Charles (1972). The Politicians Vs. the Generals: The Decline of the Brazilian Army During the First Empire, 1822–1831. University of Washington Press.

- Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars, Volume I: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 1574884492.

- Vale, Brian (2000). A War Betwixt Englishmen Brazil Against Argentina on the River Plate 1825–1830. I. B. Tauris.

In Portuguese

- Barroso, Gustavo (2019). História Militar do Brasil (PDF). Brasilia: Senado Federal. ISBN 978-85-7018-495-5.

- Bento, Cláudio Moreira (2003). 2002: 175 Anos da batalha do Passo do Rosário (PDF). Porto Alegre: Genesis. ISBN 85-87578-07-3.

- Calmon, Pedro (2002). História da Civilização Brasileira (PDF). Brasilia: Senado Federal.

- Câmara dos Deputados (1828). "Carta de Lei de 30 de Agosto de 1828" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Carneiro, David (1946). História da Guerra Cisplatina (PDF). São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.

- Donato, Hernâni (1996). Dicionário das Batalhas Brasileiras. Instituição Brasileira de Difusão Cultural. ISBN 8534800340.

- Garcia, Rodolfo (2012). Obras do Barão do Rio Branco VI: efemérides brasileiras (PDF). Brasília: Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão. ISBN 978-85-7631-357-1.

- Lustosa, Isabel (2007). Perfis Brasileiros - D. Pedro I. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-35-90807-7.

In Spanish

- Baldrich, Juan Amadeo (1974). Historia de la Guerra del Brasil. Buenos Aires: EUDEBA.

- Vale, Brian (2005). Una guerra entre ingleses. Buenos Aires: Instituto de Publicaciones Navales.

External links

Media related to Cisplatine War at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cisplatine War at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)