Indigenous architecture

The field of Indigenous architecture refers to the study and practice of architecture of, for and by Indigenous people. It is a field of study and practice in the United States, Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, Canada, Arctic area of Sápmi and many other countries where Indigenous people have a built tradition or aspire translate or to have their cultures translated in the built environment. This has been extended to landscape architecture, urban design, planning, public art, placemaking and other ways of contributing to the design of built environments.

Australia

The traditional or vernacular architecture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia varied to meet the lifestyle, social organisation, family size, cultural and climatic needs and resources available to each community.[1]

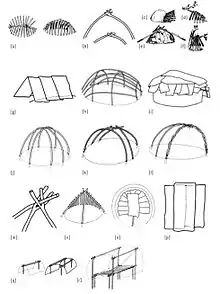

The types of forms varied from dome frameworks made of cane through spinifex-clad arc-shaped structures, to tripod and triangular shelters and elongated, egg-shaped, stone-based structures with a timber frame to pole and platform constructions. Annual base camp structures, whether dome houses in the rainforests of Queensland and Tasmania or stone-based houses in south-eastern Australia, were often designed for use over many years by the same family groups. Different language groups had differing names for structures. These included humpy, gunyah (or gunya), goondie, wiltja and wurley (or wurlie).

Until the 20th century, non-Indigenous peoples assumed that Aboriginal people lacked permanent buildings, likely because Aboriginal ways of life were misinterpreted during early contact with Europeans. Labelling Aboriginal communities as 'nomadic' allowed early settlers to justify the takeover of Traditional Lands claiming that they were not inhabited by permanent residents.

Stone engineering was utilised by a number of Indigenous language groups.[2] Examples of Aboriginal stone structures come from Western Victoria's Gunditjmara peoples.[3][4][5] These builders utilised basalt rocks around Lake Condah to erect housing and complicated systems of stone weirs, fish and eel traps and gates in water courses creeks. The lava-stone homes had circular stone walls over a metre high and topped with a dome roof made of earth or sod cladding. Evidence of sophisticated stone engineering has been found in other parts of Australia. As late as 1894, a group of around 500 people still lived in houses near Bessibelle that were constructed out of stone with sod cladding on a timber-framed dome. Nineteenth-century observers also reported flat slab slate-type stone housing in South Australia's north-east corner. These dome-shaped homes were built on heavy limbs and used clay to fill in the gaps. In New South Wales’ Warringah area, stone shelters were constructed in an elongated egg shape and packed with clay to keep the interior dry.

Australian Indigenous housing design

Housing for Indigenous people living in many parts of Australia has been characterised by an acute shortage of dwellings, poor quality construction, and housing stock ill-suited to Indigenous lifestyles and preferences. Rapid population growth, shorter lifetimes for housing stock and rising construction costs have meant that efforts to limit overcrowding and provide healthy living environments for Indigenous people have been difficult for governments to achieve. Indigenous housing design and research is a specialised field within housing studies. There have been two main approaches to the design of Indigenous housing in Australia – Health and Culture.[6][7]

The cultural design model attempts to incorporate understandings of differences in Aboriginal cultural norms into housing design. There a large body of knowledge on Indigenous housing in Australia that promotes the provision and design of housing that supports Indigenous residents’ socio-spatial needs, domiciliary behaviours, cultural values and aspirations. The culturally specific needs for Indigenous housing have been identified as major factors in the success of housing and failing to recognise the varying and diverse cultural housing needs of Indigenous peoples have been cited as the reasons for Aboriginal housing failures by academics for a number of decades. Western-style housing imposes conditions on Indigenous residents that may hinder the practice of cultural norms. If adjusting to living in a particular house strains relationships, then severe stress on the occupants may result. Ross noted, "Inappropriate housing and town planning have the capacity to disrupt the social organisation, the mechanisms for maintaining smooth social relations, and support networks."[8] There are a range of cultural factors which are discussed in the literature. These include designing housing to accommodate aspects of customer behaviour such as avoidance behaviours, household group structures, sleeping and eating behaviours, cultural constructs of crowding and privacy, and responses to death. All of the literature indicates that each housing design should be approached independently to recognise the many Indigenous cultures with varying customs and practices that exist across Australia.

The health approach to housing design developed as housing is an important factor affecting the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Substandard and poorly maintained housing along with non-functioning infrastructure can create serious health risks.[9][10] The 'Housing for Health' approach developed from observations of the housing factors affecting Aboriginal peoples' health into a methodology for measuring, rating and fixing 'household hardware' deemed essential for health. The approach is based on nine 'healthy housing principles' which are the:

Contemporary Indigenous architecture in Australia

Defining what is 'Indigenous architecture' in the contemporary context is a debate in some spheres. Many researchers and practitioners generally agree that Indigenous architectural projects are those which are designed with Indigenous clients or projects that imbue Aboriginality through consultation, and advance Aboriginal agency. This latter category may include projects which are designed primarily for non-Indigenous users. Notwithstanding the definition, a range of projects have been designed for, by or with Indigenous users. The application of evidence-based research and consultation has led to museums, courts, cultural centres, keeping houses, prisons, schools and a range of other institutional and residential buildings being designed to meet the varying and differing needs and aspirations of Indigenous users.

Notable Projects include:

- Brambuk Cultural Centre (Halls Gap//Budja Budja, Grampians National Park Victoria)[12][13][14]

- Marika Alderton House (Yirrkala, Northern Territory)[15][16][17][18][19][20]

- Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre (Uluru, Northern Territory)[12][21][22][23]

- Wilcannnia Health Service (Wilcannia, New South Wales)[12][24][25]

- Birabahn Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Centre, University of Newcastle, NSW

- Girrawaa Creative Works Centre (Bathurst, New South Wales)[25][26][27][28]

- Achimbun Interpretive and Visitor Information Centre, (Weipa, Queensland)[29]

- Tjulyuru Ngaanyatjarri Cultural and Civic Centre (Warburton, Western Australia)

- Port Augusta Courts Complex (Port Augusta, South Australia)[30]

- Kurongkurl Katitjin Centre for Indigenous Australian Education and Research (Edith Cowan University, Perth, Western Australia)[31]

- Aboriginal Dance Theatre Redfern (Redfern, Sydney)

- Nyinkka-Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre (Tennant Creek, Northern Territory)[32][33][34]

- Karijini National Park Visitors Centre (Pilbara, Western Australia)

- West Kimberley Regional Prison (Derby, Western Australia)[35][36]

- Djakanimba Pavilions, (Wugularr or Beswick, North Territory)[37][38]

- Walumba Elders Centre (Warrmarn, Western Australia)

Indigenous architecture of the 21st century has been enhanced by university-trained Indigenous architects, landscape architects and other design professionals who have incorporated different aspects of traditional Indigenous cultural references and symbolism, fused architecture with ethnoarchitectural styles and pursued various approaches to the questions of identity and architecture.[39]

Prominent practitioners

- Sarah Lynn Rees (Palawa)[40]

- Danièle Hromek (Budawang/Yuin)[41][42]

- Francoise Lane[43][44]

- Bernadette Hardy (Gamilaraay/Darug)

- Siân Hromek (Budawang/Yuin)

- Linda Kennedy (Yuin)[45][46][47]

- Rueben Berg[48]

- Jefa Greenaway[49][50]

- Dillon Kombumerri[51]

- Andrew Lane[52]

- Michael Hromek (Budawang/Yuin)

- Kevin O'Brien

- Glenn Murcutt

- Gregory Burgess

Prominent researchers

- Danièle Hromek (Budawang/Yuin)

- Carroll Go-Sam (Dyirrbal gumbilbara)[53]

- Elizabeth Grant

- Paul Memmott[54]

- Timothy O'Rourke

- Paul Pholeros

- Helen Ross[55]

Indigenous design methodology

Drawing on their heritage, Indigenous designers, architects and built environment professionals from Australia often use a Country-centred design methodology, also referred to as “Country centric design”, “Country-led design”, “privileging Country in design”,[56] and “designing with Country”.[57] This methodology centres around the Indigenous experience of Country (capital C) and has been developed and used by generations of Indigenous peoples in Australia.

Canada

Canadian traditional architecture

The original Indigenous people of Canada developed complex building traditions thousands of years before the arrival of the first Europeans. Canada contained five broad cultural regions, defined by common climatic, geographical and ecological characteristics. Each region gave rise to distinctive building forms which reflected these conditions, as well as the available building materials, means of livelihood, and social and spiritual values of the resident peoples.

A striking feature of traditional Canadian architecture was the consistent integrity between structural forms and cultural values. The wigwam, (otherwise known as 'wickiup' or 'wetu), tipi and snow house were building-forms perfectly suited to their environments and to the requirements of mobile hunting and gathering cultures. The longhouse, pit house and plank house were diverse responses to the need for more permanent building forms.

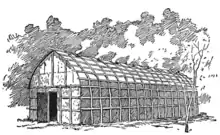

The semi-nomadic peoples of the Maritimes, Quebec, and Northern Ontario, such as the Mi'kmaq, Cree, and Algonquin generally lived in wigwams '. The wood framed structures, covered with an outer layer of bark, reeds, or woven mats; usually in a cone shape, although sometimes a dome. The groups changed locations every few weeks or months. They would take the outer layer of the structure with them, and leave the heavy wood frame in place. The frame could be reused if the group returned to the location at a later date.

Further south, in what is today Southern Ontario and Quebec the Iroquois society lived in permanent agricultural settlements holding several hundred to several thousand people. The standard form of housing was the long house. These were large structures, several times longer than they were wide holding a large number of people. They were built with a frame of saplings or branches, covered with a layer of bark or woven mats.

On the Prairies the standard form of life was a nomadic one, with the people often moving to a new location each day to follow the bison herds. Housing thus had to be portable, and the tipi was developed. The tipi consisted of a thin wooden frame and an outer covering of animal hides. The structures could be quickly erected, and were light enough to transport long distances.

In the Interior of British Columbia the standard form of home was the semi-permanent pit house, thousands of relics of which, known as quiggly holes are scattered across the Interior landscape. These were structures shaped like an upturned bowl, placed on top of a 3-or-4-foot-deep (0.91 or 1.22 m) pit. The bowl, made of wood, would be covered with an insulating layer of earth. The house would be entered by climbing down a ladder at the centre of the roof.

Some of the best architectural designs were made by settled people along the North American west coast. People like the Haida used advanced carpentry and joinery skills to construct large houses of red cedar planks. These were large square, solidly built houses. One advanced design was the six beam house, named for the number of beams that supported the roof, where the front of each house would be decorated with a heraldric pole that would be sometimes be brightly painted with artistic designs.

In the far north, where wood was scarce and solid shelter essential for survival, several unique and innovative architectural styles were developed. One of the most famous is the igloo, a domed structure made of snow, which was quite warm. In the summer months, when the igloos melted, tents made of seal skin, or other hides, were used. The Thule adopted a design similar to the pit houses of the BC interior, but because of the lack of wood they instead used whale bones for the frame.

In addition to meeting the primary need for shelter, structures functioned as integral expressions of their occupants' spiritual beliefs and cultural values. In all five regions, dwellings performed dual roles – providing both shelter and a tangible means of linking mankind with the universe. Building-forms were often seen as metaphorical models of the cosmos, and as such they frequently assumed powerful spiritual qualities which helped define the cultural identity of the group.

The sweat lodge is a hut, typically dome-shaped and made with natural materials, used by Indigenous peoples of the Americas for ceremonial steam baths and prayer. There are several styles of structures used in different cultures; these include a domed or oblong hut similar to a wickiup, a permanent structure made of wood and earth, or even a simple hole dug into the ground and covered with planks or tree trunks. Stones are typically heated and then water poured over them to create steam. In ceremonial usage, these ritual actions are accompanied by traditional prayers and songs.

Traditional housing issues in modern Canada

As many more settlers arrived in Canada, indigenous peoples were strongly motivated to relocate to newly created reserves, where the Canadian government encouraged Aboriginal people to build permanent houses and adopt farming in place of their traditional hunting and trapping. Not familiar to this sedentary lifestyle, many of these people continued to using their traditional hunting grounds, but when much of southern Canada was settled in the late 1800s and early 1900s, this practice ceased ending their nomadic way of life. After World War II indigenous people were relative non-participants in the housing and economic boom Canada. Most remained on remote rural reserves often in crowded dwellings that mostly lacked basic amenities. As health services on Aboriginal reserves increased during the 1950s and 1960s, life expectancy greatly improved including dramatic drop in the infant mortality, though this may have exacerbated the existing overcrowding problem.

Since the 1960s the living conditions in on-reserve housing in Canada has not improved significantly. Overcrowding remains a serious problem in many communities. Many houses are in serious need of repair and others still lack basic amenities. Poor conditions of housing on reservations has contributed to many Aboriginal people leaving reserves and migrating to urban areas of Canada, causing issues with homelessness, child poverty, tenancy, and transience.

Contemporary indigenous Canadian and Métis architecture

Notable projects include:

- First Nations Longhouse (University of British Columbia Vancouver)[58][59]

- MacOdrum Library, (Carleton University), (Ottawa, Ontario)

- The Canadian Museum of History (French: Musée canadien de l’histoire,(Gatineau, Quebec).

- The Spirit Garden, (Prince Arthur's Landing, Thunder Bay, Ontario)[60]

- First Nations University, (Regina, Saskatchewan)

- Aboriginal Gathering Place Pavilion (Capilano University, Vancouver, British Columbia)[61]

- Squamish Lil'wat Cultural Centre[62]

- Hôtel-Musée Premières Nations (Wendake Québec)

- Precious Blood Roman Catholic Church (Winnipeg)

Prominent Practitioners

- Douglas Cardinal

- Patrick Stewart

- Alfred Waugh

- Brian Porter

- Étienne Gaboury[63]

Prominent Researchers

- Wanda Dalla Costa

- David Fortin, Laurentian University, first Indigenous Director of a school of architecture in Canada[64]

- Ryan Walker[65][66]

Prominent Advocates

New Caledonia (Kanaky)

Kanak traditional architecture

Kanak cultures developed in the New Caledonia archipelago over a period of three thousand years. Today, France governs New Caledonia but has not developed a national culture. The Kanak claim for independence is upheld by a culture thought of as national by the indigenous population. Kanaks have settled over all the islands officially indicated by France as New Caledonia and Dependencies. The archipelago includes the principal island, Grande Terre, Belep Islands to the north and Isle of Pines to the south. It is bordered on the east by the Loyalty Islands, consisting of three coral atolls (Mare, Lifou, and Ouvea).

Kanak society is organised around clans, which are both social and spatial units. The clan could initially be made up of people related through a common ancestor, comprising several families. There can be between fifty and several hundred people in a clan. This basic definition of the clan has become modified over the years due to historical situations and places involving wars, disagreements, new arrivals etc. The clan structure, therefore, evolved as new people arrived and were given a place and a role in the social organisation of the clan, or through clan members leaving to join other clans.

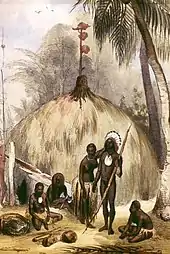

Traditionally a village is set up in the following manner. The Chief's hut (called La Grande Case) lies at the end of a long and wide central walkway which is used for gathering and performing ceremonies. The Chief's younger brother lives in a hut at the other end. The rest of the village lives in huts along the central walkway, which is lined with auracarias or palms. Trees lined the alleys which were used as shady gathering places. For Kanak people, space is divided between premises reserved for important men and other residences placed closer to the women and children. Kanak people generally avoided being alone in empty spaces.

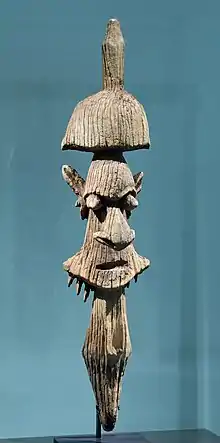

The inside of a Grande Case is dominated by the central pole (made out of houp wood), which holds up the roof and the rooftop spear, the flèche faîtière. Along the walls are various posts which are carved to represent ancestors. The door is flanked by two carved door posts (called Katana), who were the “sentinels who reported the arrival of strangers”. There also is a carved door step. The rooftop spear has three main parts: the spear facing up, which prevents bad spirits coming down onto ancestor. The face, which represents the ancestor. The spear on the bottom which keep bad spirits coming up to ancestor.

The flèche faîtière or a carved rooftop spear, spire or finial is the home of ancestral spirits and is characterized by three major components. The ancestor is symbolized by a flat, crowned face in the centre of the spear. The ancestor's voice is symbolized by a long, rounded pole that is run through by conch shells. The symbolic connection of the clan, through the chief, is a base, which is planted into the case's central pole. Sharply pointed wood pieces fan out from either end of the central area, symbolically preventing bad spirits from being able to reach the ancestor.[67] It evokes, beyond a particular ancestor, the community of ancestors.[68] and represents the ancestral spirits, symbolic of transition between the world of the dead and the world of the living.[67][69]

The arrow or the spear normally has a needle at the end to insert threaded shells from bottom to top; one of the shells contains arrangements to ensure protection of the house and the country. During wars enemies attacked this symbolic finial. After the death of a Kanak chief, the flèche faîtière is removed and his family takes it to their home. Though it is allowed to be used again, as a sign of respect, it is normally kept at burial grounds of noted citizens or at the mounds of abandoned grand houses.[69]

The form of the buildings varied from island to island, but were generally round in plan and conical in the vertical elevation. The traditional hut features represent the organization and lifestyle of the occupants. The hut is the endogenous Kanak architectural element and built entirely of plant material taken from the surrounding forest reserve. Consequently, from one area to another, the materials used are different. Inside the hut, a hearth is built on the floor between the entrance and the centre pole that defines a collective living space covered with pandanus leaf (ixoe) woven mats, and a mattress of coconut leaves (behno). The round hut is the translation of physical and material into Kanak cultures and social relations within the clan.

Detail of carved door posts (Katana)

Detail of carved door posts (Katana) Detail of carved door posts (Katana)

Detail of carved door posts (Katana) Interior view of hut with a hearth

Interior view of hut with a hearth Exhibit of the various stages of construction of a Kanak hut

Exhibit of the various stages of construction of a Kanak hut

Kanak contemporary architecture

Contemporary Kanak society has several layers of customary authority, from the 4,000–5,000 family-based clans to the eight customary areas (aires coutumières) that make up the territory.[70] Clans are led by clan chiefs and constitute 341 tribes, each headed by a tribal chief. The tribes are further grouped into 57 customary chiefdoms (chefferies), each headed by a head chief, and forming the administrative subdivisions of the customary areas.[70]

The Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre (French: Centre Culturel Tjibaou) designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano and opened in 1998 is the icon of the Kanak culture and contemporary Kanak architecture.

The Centre was constructed on the narrow Tinu Peninsula, approximately 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) northeast of the centre of Nouméa, the capital of New Caledonia, celebrates the vernacular Kanak culture, amidst much political controversy over the independent status sought by Kanaks from French rule. It was named after Jean-Marie Tjibaou, the leader of the independence movement who was assassinated in 1989 and who had a vision of establishing a cultural centre which blended the linguistic and artistic heritage of the Kanak people.[71][72]

The Kanak building traditions and the resources of modern international architecture were blended by Piano. The formal curved axial layout, 250 metres (820 ft) long on the top of the ridge, contains ten large conical cases or pavilions (all of different dimensions) patterned on the traditional Kanak Grand Hut design. The building is surrounded by landscaping which is also inspired by traditional Kanak design elements.[72][73][74] Marie Claude Tjibaou, widow of Jean Marie Tjibaou and current leader of the Agency for the Development of Kanak Culture (ADCK), observed: "We, the Kanaks, see it as a culmination of a long struggle for the recognition of our identity; on the French Government’s part it is a powerful gesture of restitution."[72]

The building plans, spread over an area of 8,550 square metres (92,000 sq ft) of the museum, were conceived to incorporate the link between the landscape and the built structures in the Kanak traditions. The people had been removed from their natural landscape and habitat of mountains and valleys and any plan proposed for the art centre had to reflect this aspect. Thus, the planning aimed at a unique building which would be, as the architect Piano stated, "to create a symbol and ...a cultural centre devoted to Kanak civilization, the place that would represent them to foreigners that would pass on their memory to their grand children". The model as finally built evolved after much debate in organized 'Building Workshops' in which Piano's associate, Paul Vincent and Alban Bensa, an anthropologist of repute on Kanak culture were also involved.

The Kanak village planning principles placed the houses in groups with the Chief's house at the end of an open public alley formed by other buildings clustered along on both sides was adopted in the Cultural Centre planned by Piano and his associates. An important concept that evolved after deliberations in the 'building workshops, after Piano won the competition for building the art centre, also involved "landscaping ideas" to be created around each building. To this end, an interpretative landscape path was conceived and implemented around each building with series of vegetative cover avenues along the path that surrounded the building, but separated it from the lagoon. This landscape setting appealed to the Kanak people when the centre was inaugurated. Even the approach to the buildings from the paths catered to the local practices of walking for three quarters of the path to get to the entrance to the Cases. One critic of the building observed: "It was very intelligent to use the landscape to introduce the building. This is the way the Kanak people can understand".[75]

The centre comprises an interconnected series of ten stylised grandes cases (chiefs' huts), which form three villages (covering an area of 6060 square metres). These huts have an exposed stainless-steel structure and are constructed of iroko, an African rot-resistant timber which has faded over time to reveal a silver patina evocative of the coconut palms that populate the coastline of New Caledonia. The Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre draws materially and conceptually on its geopolitical environment, so that despite being situated on the outskirts of the capital city, it draws influence from the diverse Kanak communities residing elsewhere across Kanaky. The circling pathway that leads from the car park to the centre's entrance is lined with plants from various regions of Kanaky. Together, these represent the myth of the creation of the first human: the founding hero, Téâ Kanaké. Signifying the collaborative design process, the path and centre are organically interconnected so it is difficult to discern any discrete edges existing between the building and gardens. Similarly, the soaring huts appear unfinished as they open outward to the sky, projecting the architect's image of Kanak culture as flexible, diasporic, progressive and resistant to containment by traditional museological spaces.

Other important architectural projects have included the construction of the Mwâ Ka, 12m totem pole, topped by a grande case (chief's hut) complete with flèche faîtière standing in a landscaped square opposite Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie. Mwâ Ka means the house of mankind – in other words, a house where discussions are held. Its carvings are divided into eight cylindrical sections representing the eight customary regions of New Caledonia. Mounted on a concrete double-hulled pirogue, the Mwâ Ka symbolises the mast but also the central post of a case. At the back of the pirogue a wooden helmsman steers the ever forwards. The square's flowerbed arrangements depicting stars and moons are symbolic of navigation. The Mwâ Ka was conceived by the Kanak community to commemorate 24 September, the anniversary of the French annexation of New Caledonia in 1853. Initially a day of mourning, the creation of the Mwâ Ka (inaugurated in 2005) symbolised the end of the mourning period thus giving the date a new significance. The erection of the Mwâ Ka was a way of burying past suffering related to French colonisation and turning a painful anniversary into a day for celebrating Kanak identity and the new multi-ethnic identity of Kanaky.

New Zealand/Aotearoa

Traditional Māori architecture

The first known dwellings of the ancestors of Māori were based on houses from their Polynesian homelands (Māori ancestors migrated from eastern Polynesia to the New Zealand archipelago {{circa | 1400 CE). On arriving, the Polynesians found they needed warmth and protection from a climate markedly different from the warm and humid tropical Polynesian islands. The early colonisers soon modified their construction techniques to suit the colder climate. Many traditional island building-techniques were retained, using new materials: raupo reed, toetoe grass, aka vines[76] and native timbers: totara, pukatea and manuka. Archeological evidence suggests that the design of Moa-hunter sleeping houses in the very early years of settlement was similar to that of houses found in Tahiti and eastern Polynesia. These were rectangular, round, oval, or "boat-shaped" semi-permanent dwellings.

These buildings were semi-permanent, as people moved around looking for food sources. Houses had wooden frames covered in reeds or leaves, with mats on earth floors. To help people keep warm, houses were small, with low doors, earth insulation and a fire inside. The standard building in a Māori settlement was a simple sleeping whare puni (house/hut) about 2 metres x 3 metres with a low roof, an earth floor, no window and a single low doorway. Heating was provided by a small open fire in winter. There was no chimney. Materials used in construction varied between areas, but raupo reeds, flax and totara-bark shingles for the roof were common.[77] Similar small whare, but with interior drains, were used to store kumara on sloping racks. Around the 15th century communities became bigger and more settled. People built wharepuni – sleeping houses with room for several families, and a front porch. Other buildings included pātaka (storehouses), sometimes decorated with carvings, and kāuta (cooking houses).[78]

The classic phase of Māori culture (1350–1769) was characterized by a more developed tribal society expressing itself clearly in wood carving and architecture. The most spectacular building type was the whare-whakairo, or carved meeting house. This building was the focus of social and symbolic Maori assemblies, and made visible a long tribal history. The wall slabs depicted warriors, chiefs and explorers. The painted rafter patterns and tukutuku panels demonstrated the Māori love for land, forest and river. The whare-whakairo was a colourful synthesis of carved architecture, expressing reverence for ancestors and love of nature. In the classic period, a higher proportion of whare were located inside pā than was the case after contact with Europeans. The whare of a chief was similar but larger—often with full headroom in the centre, a small window and a partly enclosed front porch. In times of conflict the chief lived in a whare on the tihi (summit) of a hill pā. In colder areas, such as in the North Island central plateau, it was common for whare to be partly sunk into the ground for better insulation.

Ngāti Porou ancestor, Ruatepupuke is said to have established the tradition of whare whakairo (carved meeting houses) on the East Coast. Whare whakairo are often named after ancestors and considered to embody that person. The house is seen as an outstretched body, and can be addressed like a living being. A wharenui (literally 'big house' alternatively known as meeting houses, whare rūnanga or whare whakairo (literally "carved house") is a communal house generally situated as the focal point of a marae. The present style of wharenui originated in the early to middle nineteenth century. The houses are often carved inside and out with stylised images of the iwi's ancestors, with the style used for the carvings varying from iwi to iwi. The houses always have names, sometimes the name of an ancestor or sometimes a figure from Māori mythology. While a meeting house is considered sacred, it is not a church or house of worship, but religious rituals may take place in front of or inside a meeting house. On most marae, no food may be taken into the meeting house.[79]

Food was not cooked in the sleeping whare but in the open or under a kauta (lean-to). Saplings with branches and foliage removed were used to store and dry item such as fishing nets or cloaks. Valuable items were stored in pole-mounted storage shelters called pataka.[80][81] Other constructions were large racks for drying split fish.

The marae was the central place of the village where culture can be celebrated and intertribal obligations can be met and customs can be explored and debated, where family occasions such as birthdays can be held, and where important ceremonies, such as welcoming visitors or farewelling the dead (tangihanga), can be performed.

The building often symbolises an ancestor of the wharenui's tribe. So different parts of the building refer to body parts of that ancestor:[82]

- the koruru at the point of the gable on the front of the wharenui can represent the ancestor's head.[83] Compare finial.

- the maihi (the diagonal bargeboards) signify arms; the ends of the maihi are called raparapa, meaning "fingers"

- the tāhuhu (ridge beam) represents the backbone

- the heke or rafters signify ribs

- internally, the poutokomanawa (central column) can be interpreted as the heart[84]

Other important components of the wharenui include:[82]

- the amo, the vertical supports that hold up the ends of the maihi

- the poupou, or wall carving underneath the verandah

- the kūwaha or front door, along with the pare or door lintel

- the paepae, the horizontal element on the ground at the front of the wharenui, acts as the threshold of the building

Contemporary Māori architecture

Rau Hoskins defines Māori architecture as anything that involves a Māori client with a Māori focus. “I think traditionally Māori architecture has been confined to marae architecture and sometimes churches, and now Māori architecture manifests across all environments, so we have Māori immersion schools, Māori medical centres and health clinics, Māori tourism ventures, and papa kāinga or domestic Māori villages. So the opportunities that exist now are very diverse. The kaupapa (purpose or reason) for the building and client’s aspirations are the key to how the architecture manifests.”[85]

From the 1960s, marae complexes were built in urban areas. In contemporary context these generally comprise a group of buildings around an open space, that frequently host events such as weddings, funerals, church services and other large gatherings, with traditional protocol and etiquette usually observed. They also serve as the base of one or sometimes several hapū.[86] The marae is still wāhi tapu, a 'sacred place' which carries cultural meaning. They included buildings such as wharepaku (toilets) and whare ora (health centres). Meeting houses were still one large space with a porch and one door and window in front. In the 1980s marae began to be built in prisons, schools and universities.

Notable projects include:

- Tānenuiarangi, Wharenui at Waipapa Marae, (University of Auckland)

- Māori Studies facilities, UNITEC and Tairawhiti Polytechnic

- Ruapoutaka Marae, Glen Innes

- Ngäti Otara Marae and Te Rawheoro Marae (Tolaga Bay)

- Futuna Chapel (Karori, Wellington)

Prominent practitioners

- John Scott

- Rewi Thompson (Ngāti Porou and Ngāti Raukawa)[87][88]

- Elisapeta Heta (Ngāti Wai) [89][90][91]

- Keri Whaitiri, (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tahu)[92]

- Tere Insley (Te Whānau-ā-Apanui) [93][94]

- Haley Hooper (Ngāpuhi) [95]

- Jade Kake, (Ngāpuhi (Ngāti Hau me Te Parawhau), Te Whakatōhea, Te Arawa)[96][97][98]

- Raukura Turei (Ngāitai ki Tamaki and Ngā Rauru ki Tahi) [99][100][101]

- Amanda Yates (Ngāti Rangiwewehi, Ngāti Whakaue, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Rongowhakaata)

- Jacqueline Paul (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga)[102]

- Fleur Palmer (Te Rarawa, Te Aupouri)[103]

- Rau Hoskins[104][105]

Prominent researchers

- Elsdon Best

- Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu )[106][107]

- Fleur Palmer (Te Rarawa, Te Aupouri)[103]

Sápmi

Traditional architecture (ethno-architecture) of the Sámi

Sápmi is the term for Sámi (also Saami) traditional lands. The Sámi people are the Indigenous people of the northern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula and large parts of the Kola Peninsula, which encompasses parts of far northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, and the border area between south and middle Sweden and Norway. The Sámi are the only Indigenous people of Scandinavia recognized and protected under the international conventions of indigenous people, and the northernmost Indigenous people of Europe. Sámi ancestral lands span an area of approximately 388,350 km2 (150,000 sq. mi.) across the Nordic countries.

There are a number of Sámi ethnoarchitectural forms; including the lavvu, goahti, the Finnish laavu. The differences between the goahti and the lavvu can be seen when looking at the top of structures. A lavvu will have its poles coming together, while the goahti will have its poles separate and not coming together. The turf version of the goahti will have the canvas replaced with wood resting on the structure covered with birch bark then peat to provide a durable construction.

Lavvu (or Northern Sami: lávvu, Inari Sami: láávu, Skolt Sami: kååvas, Kildin Sami: koavas, Finnish: kota or umpilaavu, Norwegian: lavvo or sametelt, and Swedish: kåta) is a structure built by the Sámi of northern Scandinavia. It has a design similar to a Native American tipi but is less vertical and more stable in high winds. It enables the indigenous cultures of the treeless plains of northern Scandinavia and the high arctic of Eurasia to follow their reindeer herds. It is still used as a temporary shelter by the Sámi, and increasingly by other people for camping.

There are several historical references that describe the lavvu structure (also called a kota, or a variation on this name) used by the Sami. These structures have the following in common:[108][109][110][111][112]

- The lavvu is supported by three or more evenly spaced forked or notched poles that form a tripod.

- There are upwards of ten or more unsecured straight poles that are laid up against the tripod and which give form to the structure.

- The lavvu does not need any stakes, guy-wire or ropes to provide shape or stability to the structure.

- The shape and volume of the lavvu is determined by the size and quantity of the poles that are used for the structure.

- There is no center pole needed to support this structure.

No historical record has come to light that describes the Sami using a single-pole structure claimed to be a lavvu, or any other Scandinavian variant name for the structure. The definition and description of this structure has been fairly consistent since the 17th century and possibly many centuries earlier.

A goahti (also gábma, gåhte, gåhtie and gåetie, Norwegian: gamme, Finnish: kota, Swedish: kåta), is a Sami hut or tent of three types of covering: fabric, peat moss or timber. The fabric-covered goahti looks very similar to a Sami lavvu, but often constructed slightly larger. In its tent version the goahti is also called a 'curved pole' lavvu, or a 'bread box' lavvu as the shape is more elongated while the lavvu is in a circular shape.

The interior construction of the poles is thus: 1) four curved poles (8–12 feet (2.4–3.7 m) long), 2) one straight center pole (5–8 feet (1.5–2.4 m) long), and 3) approximately a dozen straight wall-poles (10–15 feet (3.0–4.6 m) long). All the pole sizes can vary considerably.

The four curved poles curve to about a 130° angle. Two of these poles have a hole drilled into them at one end, with those ends being joined together by the long center pole that is inserted by the described poles. The other two curved poles are also joined at the other end of the long pole. When this structure is set up, a four-legged stand is formed with the long pole at the top and center of the structure. With the four-legged structure standing up to about five to eight feet in height, approximately ten or twelve straight "wall-poles" are laid up against the structure. The goahti covering, today made usually of canvas, is laid up against the structure and tied down. There can be more than one covering that covers the structure.

Contemporary Sámi architecture

_4.jpg.webp)

The Sámi Parliament building was designed by the architects Stein Halvorsen & Christian Sundby, who won the Norwegian government's call for projects in 1995, and inaugurated in 2005. The government called for a building such that “the Sámi Parliament appears dignified” and “reflects Sámi architecture.”

Notable Projects include:

- The Sámi Parliament Building, Norway.

- Várjjat Sámi Musea (Varanger Sami Museum, VSM), Nesseby, Finnmark

Samoa

Traditional architecture (ethno-architecture) of Samoa

The architecture of Samoa is characterised by openness, with the design mirroring the culture and life of the Samoan people who inhabit the Samoa Islands.[113] Architectural concepts are incorporated into Samoan proverbs, oratory and metaphors, as well as linking to other art forms in Samoa, such as boat building and tattooing. The spaces outside and inside of traditional Samoan architecture are part of cultural form, ceremony and ritual. Fale is the Samoan word for all types of houses, from small to large. In general, traditional Samoan architecture is characterized by an oval or circular shape, with wooden posts holding up a domed roof. There are no walls. The base of the architecture is a skeleton frame. Before European arrival and the availability of Western materials, a Samoan fale did not use any metal in its construction.

The fale is lashed and tied together with a plaited sennit rope called ʻafa, handmade from dried coconut fibre. The ʻafa is woven tight in complex patterns around the wooden frame, and binds the entire construction together. ʻAfa is made from the husk of certain varieties of coconuts with long fibres, particularly the niu'afa (afa palm). The husks are soaked in fresh water to soften the interfibrous portion. The husks from mature nuts must be soaked from four to five weeks, or perhaps even longer, and very mature fibre is best soaked in salt water, but the green husk from a special variety of coconut is ready in four or five days. Soaking is considered to improve the quality of the fibre. Old men or women then beat the husk with a mallet on a wooden anvil to separate the fibres, which, after a further washing to remove interfibrous material, are tied together in bundles and dried in the sun. When this stage is completed, the fibres are manufactured into sennit by plaiting, a task usually done by elderly men or matai, and performed at their leisure. This usually involves them seated on the ground rolling the dried fibre strands against their bare thigh by hand, until heavier strands are formed. These long, thin strands are then woven together into a three-ply plait, often in long lengths, that is the finished sennit. The sennit is then coiled in bundles or wound tightly in very neat cylindrical rolls.[114]

Making enough lengths of afa for an entire house can take months of work. The construction of an ordinary traditional fale is estimated to use 30,000 to 50,000 feet of ʻafa. The lashing construction of the Samoan fale is one of the great architectural achievements of Polynesia.[115] A similar lashing technique was also used in traditional boat building, where planks of wood were 'sewn' together in parts. ʻAfa has many other uses in Samoan material culture, including ceremonial items, such as the fue fly whisk, a symbol of orator status. This lashing technique was also used in other parts of Polynesia, such case the magimagi of Fiji.

The form of a fale, especially the large meeting houses, creates both physical and invisible spatial areas, which are clearly understood in Samoan custom, and dictate areas of social interaction. The use and function of the fale is closely linked to the Samoan system of social organisation, especially the Fa'amatai chiefly system.

Those gathered at a formal gathering or fono are always seated cross-legged on mats on the floor, around the fale, facing each other with an open space in the middle. The interior directions of a fale, east, west, north and south, as well as the positions of the posts, affect the seating positions of chiefs according to rank, the place where orators (host or visiting party) must stand to speak or the side of the house where guests and visitors enter and are seated. The space also defines the position where the 'ava makers (aumaga) in the Samoa 'ava ceremony are seated and the open area for the presentation and exchanging of cultural items such as the 'ie toga fine mats.

The front of a Samoan house is that part that faces the main thoroughfare or road through the village. The floor is quartered, and each section is named: Tala luma is the front side section, tala tua the back section, and tala, the two end or side sections.[116] The middle posts, termed matua tala are reserved for the leading chiefs and the side posts on the front section, termed pou o le pepe are occupied by the orators. The posts at the back of the house, talatua, indicate the positions maintained by the 'ava makers and others serving the gathering.[116]

The immediate area exterior of the fale is usually kept clear, and is either a grassy lawn or sandy area if the village is by the sea. The open area in front of the large meeting houses, facing the main thoroughfare or road in a village, is called the malae, and is an important outdoor area for larger gatherings and ceremonial interaction. The word "fale" is also constructed with other words to denote social groupings or rank, such as the faleiva (house of nine) orator group in certain districts. The term is also used to describe certain buildings and their functions. The word for hospital is falema'i, "house of the ill".

The simplest types of fale are called faleo'o, which have become popular as ecofriendly and low-budget beach accommodations in local tourism. Every family complex in Samoa has a fale tele, the meeting house, "big house". The site on which the house is built is called tulaga fale (place to stand).[116]

The builders in Samoan architecture were also the architects, and they belonged to an exclusive ancient guild of master builders, Tufuga fau fale. The Samoan word tufuga denotes the status of master craftsmen who have achieved the highest rank in skill and knowledge in a particular traditional art form. The words fau-fale means house builder. There were Tufuga of navigation (Tufuga fau va'a) and Samoan tattooing (Tufuga ta tatau). Contracting the services of a Tufuga fau fale required negotiations and cultural custom.[117]

The fale tele (big house), the most important house, is usually round in shape, and serves as a meeting house for chief council meetings, family gatherings, funerals or chief title investitures. The fale tele is always situated at the front of all other houses in an extended family complex. The houses behind it serve as living quarters, with an outdoor cooking area at the rear of the compound.[116] At the front is an open area, called a malae. The malae, (similar to marae concept in Māori and other Polynesian cultures), is usually a well-kept, grassy lawn or sandy area. The malae is an important cultural space where interactions between visitors and hosts or outdoor formal gatherings take place.

The open characteristics of Samoan architecture are also mirrored in the overall pattern of house sites in a village, where all fale tele are situated prominently at the fore of all other dwellings in the village, and sometimes form a semicircle, usually facing seawards. In modern times, with the decline of traditional architecture and the availability of western building materials, the shape of the fale tele has become rectangular, though the spatial areas in custom and ceremony remain the same.

Traditionally, the afolau (long house), a longer fale shaped like a stretched oval, served as the dwelling house or guest house.

The faleo'o (small house), traditionally long in shape, was really an addition to the main house. It is not so well constructed and is situated always at the back of the main dwelling.[116] In modern times, the term is also used for any type of small and simple fale, which is not the main house of dwelling. Popular as a "grass hut" or beach fale in village tourism, many are raised about a meter off the ground on stilts, sometimes with an iron roof. In a village, families build a faleo'o beside the main house or by the sea for resting during the heat of the day or as an extra sleeping space at night if there are guests.

The tunoa (cook house) is a flimsy structure, small in size, and not really to be considered as a house. In modern times, the cook house, called the umukuka, is at the rear of the family compound, where all the cooking is carried out in an earth oven, umu, and pots over the fire. In most villages, the umukuka is really a simple open shed made with a few posts with an iron roof to protect the cooking area from the weather.

Construction of a fale, especially the large and important fale tele, often involves the whole extended family and help from their village community.

The Tufuga fai fale oversees the entire building project. Before construction, the family prepares the building site. Lava, coral, sand or stone materials are usually used for this purpose. The Tufuga, his assistants (autufuga) and men from the family cut the timber from the forest. The main supporting posts, erected first, vary in number, size and length depending on the shape and dimensions of the house. Usually they are between 16 and 25 feet in length and six to 12 inches in diameter, and are buried about four feet in the ground. The term for these posts is poutu (standing posts); they are erected in the middle of the house, forming central pillars.

Attached to the poutu are cross pieces of wood of a substantial size called so'a. The so'a extend from the poutu to the outside circumference of the fale and their ends are fastened to further supporting pieces called la'au fa'alava.

The la'au fa'alava, placed horizontally, are attached at their ends to wide strips of wood continuing from the faulalo to the auau. These wide strips are called ivi'ivi. The faulalo is a tubular piece (or pieces) of wood about four inches in diameter running around the circumference of the house at the lower extremity of the roof, and is supported on the poulalo. The auau is one or more pieces of wood of substantial size resting on the top of the poutu. At a distance of about two feet between each are circular pieces of wood running around the house and extending from the faulalo to the top of the building. They are similar to the faulalo.

The poulalo are spaced about three to four feet apart and are sunk about two feet in the ground. They average three to four inches in diameter, and extend about five feet above the floor of the fale. The height of the poulalo above the floor determines the height of the lower extremity of the roof from the ground.

On the framework are attached innumerable aso, thin strips of timber (about half an inch by a quarter by 12 to 25 feet in length). They extend from the faulalo to the ivi'ivi, and are spaced from one to two inches apart. Attached to these strips at right angles are further strips, paeaso, the same size as aso. As a result, the roof of the fale is divided into an enormous number of small squares.[116]

Most of the timber is grown in forests on family land. The timber was cut in the forest and carried to the building site in the village. The heavy work involved the builder's assistants, members of the family and help from the village community. The main posts were from the breadfruit tree (ulu), or ifi lele or pou muli if this wood was not available. The long principal rafters had to be flexible, so coconut wood (niu) was always selected. The breadfruit tree was also used for other parts of the main framework.

In general, the timbers most frequently used in the construction of Samoan houses are:- Posts (poutu and poulalo): ifi lele, pou muli, asi, ulu, talia, launini'u and aloalovao. Fau: ulu, fau, niu, and uagani Aso and paeso: niuvao, ulu, matomo and olomea The auau and talitali use ulu and the so'a used both ulu and niu.

The completed, domed framework is covered with thatch (lau leaves), which is made by the women. The best quality of thatch is made with the dry leaves of the sugarcane. If sugarcane leaf was not available, the palm leaves of the coconut tree was used in the same manner. The long, dry leaves are twisted over a three-foot length of lafo, which are then fastened by a thin strip of the frond of the coconut being threaded through the leaves close up to the lafo stem. These sections of thatch are fastened to the outside of the framework of the fale beginning at the bottom and working up to the apex. They are overlapped, so each section advances the thatching about three inches. This means there is really a double layer of thatch covering the whole house. The sections are fastened to the aso at each end by afa.

Provided the best quality of thatch is used and it has been truly laid, it will last about seven years. On an ordinary dwelling house, about 3000 sections of thatch are laid. Protection from sun, wind or rain, as well as from prying eyes, was achieved by suspending from the fau running round the house several of a sort of drop-down Venetian blind, called pola. The fronds of the coconut tree are plaited into a kind of mat about a foot wide and three feet long. A sufficient number of pola to reach from the ground to the top of the poulalo are fastened together with afa and are tied up or let down as the occasion demands. Usually, one string of these mats covers the space between two poulalo and so on round the house. They do not last for long, but being quickly made, are soon replaced. They afford ample protection from the elements, and it being possible to let them down in sections; seldom is the whole house is closed up.

The natural foundations of a fale site are coral, sand, and lava, with sometimes a few inches of soil in some localities. Drainage is therefore good. The top layers of the flooring are smooth pebbles and stones. When occupied, the house floors are usually covered or partially covered with native mats.

In Samoan mythology, an explanation of why Samoan houses are round is explained in a story about the god Tagaloa, also known as Tagaloalagi (Tagaloa of the Heavens).

Following is the story, as told by Samoan historian Te'o Tuvale in An Account of Samoan History up to 1918.

- During the time of Tagaloalagi, the houses in Samoa varied in shape, and this led to many difficulties for those who wished to have a house built in a certain manner. Each carpenter was proficient in building a house of one particular shape only, and it was sometimes impossible to obtain the services of the carpenter desired. A meeting of all the carpenters in the country was held to try to decide on some uniform shape. The discussion waxed enthusiastic, and as there seemed no prospect of a decision being arrived at, it was decided to call in the services of Tagaloalagi. After considering the matter, he pointed to the dome of Heaven and to the horizon and he decreed that in future, all houses built would be of that shape, and this explains why all the ends of Samoan houses are as the shape of the heavens extending down to the horizon.[116] An important tree in Samoan architecture is the coconut palm. In Samoan mythology, the first coconut tree is told in a legend called Sina and the Eel.

Fiji

Traditional architecture (ethno-architecture) of Fiji

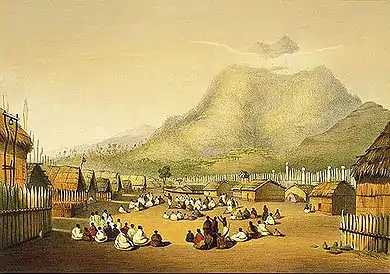

.jpg.webp)

In Old Fiji, the architecture of villages was simple and practical to meet the physical and social need and to provide communal safety. The houses were square in shape and with pyramid like shaped roofs,[118] and the walls and roof were thatched and various plants of practical use were planted nearby, each village having a meeting house and a Spirit house. The spirit house was elevated on a pyramid like base built with large stones and earth, again a square building with an elongated pyramid like [118] roof with various scented flora planted nearby.

The houses of Chiefs were of similar design and would be set higher than his subjects houses but instead of an elongated roof would have similar roof to those of his subjects homes but of course on a larger scale.

Contemporary architecture in Fiji

With the introduction of communities from Asia aspects of their cultural architecture are now evident in urban and rural areas of Fiji's two main Islands Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. A village structure shares similarities today but built with modern materials and spirit houses (Bure Kalou) have been replaced by churches of varying design.

The urban landscape of early Colonial Fiji was reminiscent of most British colonies of the 19th and 20th century in tropical regions of the world, while some of this architecture remains, the urban landscape is evolving in leaps and bounds with various modern aspects of architecture and design becoming more and more evident in the business, industrial and domestic sector, the rural areas are evolving at a much slower rate.

Palau

Traditional architecture (ethno-architecture) of Palau

.jpg.webp)

In Palau there is many traditional meeting houses known as bais or abais.[119] In ancient times every village in Palau had a bai as it was the most important building in a village.[120] At the beginning of the 20th century, more than 100 bais were still in existence in Palau.[121] In bais governing elders are assigned seats along the walls, according to rank and title.[120] A bai has no dividing walls or furnishing and is decorated with depictions of Palauan legends.[120] Palau's oldest bai is Airai Bai which is over 100 years old.[122] Bais feature on the Seal of Palau and the flag of Koror.[123]

United States

Traditional architecture (ethno-architecture) of Hawai'i

Within the body of Hawai'ian architecture are various subsets of styles; each are considered typical of particular historical periods. The earliest form of Hawaiian architecture originates from what is called ancient Hawaiʻi—designs employed in the construction of village shelters from the simple shacks of outcasts and slaves, huts for the fishermen and canoe builders along the beachfronts, the shelters of the working class makaʻainana, the elaborate and sacred heiau of kahuna and the palatial thatched homes on raised basalt foundation of the aliʻi. The way a simple grass shack was constructed in ancient Hawaiʻi was telling of who lived in a particular home. The patterns in which dried plants and lumber were fashioned together could identify caste, skill and trade, profession and wealth. Hawaiian architecture previous to the arrival of British explorer Captain James Cook used symbolism to identify religious value of the inhabitants of certain structures. Feather standards called kahili and koa adorned with kapa cloth and crossed at the entrance of certain homes called puloʻuloʻu indicated places of aliʻi (nobility caste). Kiʻi enclosed within basalt walls indicated the homes of kahuna (priestly caste).

Puebloan architecture

Pueblo-style architecture imitates the appearance of traditional Pueblo adobe construction, though other materials such as brick or concrete are often substituted. If adobe is not used, rounded corners, irregular parapets, and thick, battered walls are used to simulate it. Walls are usually stuccoed and painted in earth tones. Multistory buildings usually employ stepped massing similar to that seen at Taos Pueblo. Roofs are always flat. Common features of the Pueblo Revival style include projecting wooden roof beams or vigas, which sometimes serve no structural purpose, "corbels", curved—often stylized—beam supports and latillas, which are peeled branches or strips of wood laid across the tops of vigas to create a foundation (usually supporting dirt or clay) for a roof.[124][125]

Philippines

Traditional architecture (ethno-architecture) of the Philippines

The Bahay Kubo, Kamalig, or Nipa Hut, is a type of stilt house indigenous to most of the lowland cultures of the Philippines.[126][127] It often serves as an icon of broader Filipino culture, or, more specifically, Filipino rural culture.[128]

Although there is no strict definition of the Bahay Kubo and styles of construction vary throughout the Philippine archipelago,[129] similar conditions in Philippine lowland areas have led to numerous characteristics "typical" of examples of Bahay Kubo.

With few exceptions arising only in modern times, most Bahay Kubo are raised on stilts such that the living area has to be accessed through ladders. This naturally divides the bahay kubo into three areas: the actual living area in the middle, the area beneath it (referred to in Tagalog as the "Silong"), and the roof space ("Bubungan" in Tagalog), which may or may not be separated from the living area by a ceiling ("Kisame" in Tagalog).

The traditional roof shape of the Bahay Kubo is tall and steeply pitched, ending in long eaves.[127] A tall roof created space above the living area through which warm air could rise, giving the Bahay Kubo a natural cooling effect even during the hot summer season. The steep pitch allowed water to flow down quickly at the height of the monsoon season while the long eaves gave people a limited space to move about around the house's exterior whenever it rained.[127] The steep pitch of the roofs are often used to explain why many Bahay Kubo survived the ash fall from the Mt. Pinatubo eruption, when more ’modern’ houses notoriously collapsed from the weight of the ash.[127]

Raised up on hardwood stilts which serve as the main posts of the house, Bahay Kubo have a Silong (the Tagalog word also means "shadow") area under the living space for a number of reasons, the most important of which are to create a buffer area for rising waters during floods, and to prevent pests such as rats from getting up to the living area.[127] This section of the house is often used for storage, and sometimes for raising farm animals,[129] and thus may or may not be fenced off.

The main living area of the Bahay Kubo is designed to let in as much fresh air and natural light as possible. Smaller Bahay Kubo will often have bamboo slat floors which allow cool air to flow into the living space from the silong below (in which case the Silong is not usually used for items which produce strong smells), and the particular Bahay Kubo may be built without a kisame (ceiling) so that hot air can rise straight into the large area just beneath the roof, and out through strategically placed vents there.

The walls are always of light material such as wood, bamboo rods, or bamboo mats called "sawali." As such, they tend to also let some coolness flow naturally through them during hot times, and keep warmth in during the cold wet season. The cube shape distinctive of the Bahay Kubo arises from the fact that it is easiest to pre-build the walls and then attach them to the wooden stilt-posts that serve as the corners of the house. The construction of a Bahay Kubo is therefore usually modular, with the wooden stilts established first, a floor frame built next, then wall frames, and finally, the roof.

In addition, bahay kubo are typically built with large windows, to let in more air and natural light. The most traditional are large awning windows, held open by a wooden rod.[127] Sliding windows are also common, made either with plain wood or with wooden Capiz shell frames, which allow some light to enter the living area even with the windows closed. In more recent decades inexpensive jalousie windows also became commonly used. In larger examples, the large upper windows may be augmented with smaller windows called ventanillas (Spanish for "little window) underneath, which can be opened to let in additional air, especially hot days.[127]

Some (but not all) Bahay Kubo, especially one built for long-term residence, feature a Batalan "wet area" distinct from other sections of the house – usually jutting out somewhat from one of the walls. Sometimes at the same level as the living area and sometimes at ground level, the Batalan can contain any combination of cooking and dishwashing area, bathing area, and in some cases, a lavatory.

The walls of the living area are made of light materials – with posts, walls, and floors typically made of wood or bamboo and other light materials. Topped by a thatched roof, often made out of nipa, anahaw or some other locally plentiful plant. The Filipino term "Bahay Kubo" literally means "cube house", describing the shape of the dwelling. The term "Nipa Hut", introduced during the Philippines' American colonial era, refers to the nipa or anahaw thatching material often used for the roofs.

Nipa huts were the native houses of the indigenous people of the Philippines before the Spaniards arrived. They are still used today, especially in rural areas. Different architectural designs are present among the different ethnolinguistic groups in the country, although all of them conform to being stilt houses, similar to those found in neighboring countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and other countries of Southeast Asia. The advent of the Spanish Colonial era introduced the idea of building more permanent communities with the Church and Government Center as a focal point. This new community setup made construction using heavier, more permanent materials desirable. Finding European construction styles impractical given local conditions, both Spanish and Filipino builders quickly adapted the characteristics of the Bahay Kubo and applied it to Antillean houses locally known as Bahay na Bato (Literally "stone house" in Tagalog).[129]

References

- Memmott, Paul (2007). Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia, St Lucia, University of Queensland Press.

- Pascoe, Bruce (2014). Dark emu : black seeds agriculture or accident?. Broome, W.A. ISBN 9781922142436. OCLC 863984459.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Coutts, Peter, Frank Rudy, Hughes, Phil and Vanderwal, R. (1978). Aboriginal Engineers of the western district, Victoria. Melbourne: Aboriginal Affairs Victoria.

- Bird, Caroline and Frankel, David (1991). Chronology and explanation in western Victoria and south‐east South Australia,' Archaeology in Oceania 26 (1) pp. 1–16.

- Anna Salleh, Aborigines may have and farmed eels, built huts, News in Science, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 13 March 2003.

- Memmott, Paul (2004). Aboriginal housing: has the state of the art improved. Architecture Australia, 93 (1), pp. 46–48.

- Memmott, Paul (2003). TAKE 2: housing design in Indigenous Australia, Red Hill, The Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

- Ross, Helen (69). Just for Living: Aboriginal perceptions of housing in north-west Australia. Aboriginal Studies Press. p.6

- , Bailie, Ross and Runcie, Myfanwy J. (2001). Household Infrastructure in Aboriginal Communities and the Implications for Health Improvement. Medical Journal of Australia 175, pp. 363–366.

- Pholeros Paul, Rainow Stephan and Torzillo Paul, (1993). Housing for health: towards a healthy living environment for Aboriginal Australia. Newport Beach, New South Wales, HealthHabitat

- Nganampa Health (1987). Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku (The UPK Report). South Australian Committee of Review on Environmental and Public Health within the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands in South Australia.

- Memmott, Paul and Reser, Joseph (2000). Design concepts and processes for public Aboriginal architecture. In 11th Conference on People Physical Environment Research (PaPER – Australian Aboriginal Double Issue) 55 & 56 pp. 69 – 86.

- Johnson, R. (1990). 'Brambuk Living Cultural Centre: Winner Sir Zelman Cowen Award,' Architecture Australia pp. 26 – 28.

- Memmott, Paul (1996). 'Aboriginal signs and architectural meanings,' Architectural Theory Review, 1 (2) pp. 79–100.

- Dovey, Kim (1996).'Architecture for Aborigines', Architecture Australia, 85 (4) pp. 98 – 103

- Dovey, Kim (2000). 'Myth and media: Constructing Aboriginal architecture,' Journal of Architectural Education, 54 (1) pp 2 – 6.

- Fromonot, Françoise (2003). Glenn Murcutt: buildings + projects 1962–2003, London, Thames & Hudson

- Davies, Colin (2006). Key houses of the twentieth century: plans, sections and elevations. Laurence King Publishing

- Melhuish, C. (1996). 'Glenn Murcutt Marika-Alderton-House and Kakadu-Landscape-Interpretation-Centre (with Troppo-Architects), Northern-Territory, Australia', Architectural Design, (124) pp 40 – 45.

- Carter, Nanette (2011). 'A Site Every Design Professional Should See: The Marika-Alderton House, Yirrkala,' Design and Culture, 3 (3) pp. 375 -378.

- Tawa, Michael (2002). 'Place, Country, Chorography: Towards a Kinesthetic and Narrative Practice of Place,' Architectural Theory Review, 7 (2) pp. 45 – 58.

- Findley, Lisa (2002). 'Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre Gregory Burgess,' Baumeister, (3) pp. 74 – 79.

- Findley, Lisa (2005). Building change: Architecture, politics and cultural agency. Psychology Press.

- Memmott, Paul (2005). Positioning the Traditional Architecture of Aboriginal Australia in a World Theory of Architecture. In Informal Settlements and Affordable Housing 309 pp. 1 – 1). International Council for Research and Innovation in Building & Construction (CIB).

- Page, Alison (2003). 'Building Pride: Cultural journeys through the built environment', Australian Planner 40 (2) pp. 121 – 122

- "Arts & Culture News – ABC News". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Grant, Elizabeth (2008). 'Prison environments and the needs of Australian Aboriginal prisoners', Australian Indigenous Law Review, 12 (2) pp. 66 – 80.

- Grant, Elizabeth (2013). 'Approaches to the design and provision of prison accommodation and facilities for Australian Indigenous prisoners after the Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody', Australian Indigenous Law Review 17 (1) pp. 47 – 55.

- "Achimbun". Troppo Architects. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Grant, Elizabeth (2009). Port Augusta Courts. Architecture Australia, 98 (5) pp. 86 – 90.

- Poole, Millicent (2005). Intercultural dialogue in action within the university context: A case study' Higher Education Policy, 18 (4) pp. 429 – 435.

- "Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre / Darren Clark". Archived from the original on 2015-02-20. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- Christen, Kimberly (2006). 'Tracking properness: repackaging culture in a remote Australian town,' Cultural Anthropology 21 (3) pp. 416 – 446.

- Christen, Kimberly (2007). 'Following the Nyinkka: Relations of respect and obligations to act in the collaborative work of Aboriginal cultural centers,' Museum Anthropology 30 (2) pp. 101–124.

- Grant, Elizabeth and Hobbs, Peter (2013). 'West Kimberley Regional Prison,' Architecture Australia, 102 (4) pp. 74 – 84.

- Grant, E. (2013). 'Innovation in meeting the needs of Indigenous Inmates in Australia: West Kimberley Regional Prison' Corrections Today, September 75 (4) pp. 52 – 57

- "2013 National Architecture Awards: Nicholas Murcutt Award". Architectureau.com. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Djakanimba Pavilions | Djilpin Arts". Archived from the original on 2015-02-20. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- Memmott, Paul (2007). Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley. The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia. University of Queensland Press.

- "Sarah Rees". Art, Design and Architecture. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Daniele Hromek". University of Technology Sydney. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Danièle Hromek". Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Indigenous Textiles | Francoise Lane Art | Queensland". Francoise Lane Art. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Queensland designer in international leadership program". Arts Queensland. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Architect Bulletin | Manifesto - linda kennedy and archrival". Architect Bulletin. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "PechaKucha 20x20". www.pechakucha.com. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "ATF 2017 Keynote: Linda Kennedy - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- Adams, S., Berg, R., James, A., Kumar, S., Mullen, A. and Russell-Clarke, J.O., 2015. Victoia Landscape Architecture Awards. Landscape Architecture, 51.

- "Architecture: The next bastion of Indigenous creativity says architect Jefa Greenaway". Abc.net.au. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Johnson, Nathan. "How architecture can give voice to narratives of Indigenous culture: Jefa Greenaway". Architectureanddesign.com.au. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Kombumerri, D., 2001. Contemporary Australian Indigenous Architecture by Indigenous Designers. Governance and Sustainable Technology in Indigenous and Developing Communities, Perth, Western Australia, Murdoch University.

- Lane, A., 2008. Why we do what we do [Experiences of an architect working on Aboriginal housing.]. Architecture Australia, 97(5).

- "Carroll Go-Sam". The Conversation. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 2017-06-12.

- Memmott, P., 2007. Gunyah, Goondie+ Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia. Univ. of Queensland Press.

- Ross, H., 1987. Just for Living: Aboriginal perceptions of housing in northwest Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Hromek, Danièle Siân (2019). The (Re)Indigenisation of Space: Weaving narratives of resistance to embed Nura [Country] in design (Thesis thesis).

- "Designing with Country" (PDF). Government Architect NSW. New South Wales Government Architect. 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Kirkness, V. and Archibald, J. (2001). The First Nations Longhouse, Vancouver: First Nations House of Learning, pp.52–53

- Demerais, L. (1993). ‘First Nations Longhouse’, The Canadian Architect, pp. 15.

- "Thunder Bay's revitalized waterfront: A declaration that aboriginal culture matters". Theglobeandmail.com. Retrieved 27 August 2018 – via The Globe and Mail.

- "CAPILANO UNIVERSITY ABORIGINAL GATHERING PLACE — FormLine Architecture". Formline.ca. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Squamish Lil'wat Cultural Centre: A Triumph of Architecture and First Nations Culture". Aadnc-aandc.gc.ca. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Chaput, Lucien (2007). ""Étienne-Joseph Gaboury"". In Boyens, Ingeborg. The Encyclopedia of Manitoba. Great Plains Publications. pp. 261–262. ISBN 1894283716

- Kelly Boutsalis (18 October 2018). "Indigenous architects design a sovereign future," Now Toronto Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Walker, Ryan; Jojola, Ted (1 September 2013). Reclaiming Indigenous Planning. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. ISBN 9780773589940. Retrieved 27 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- "New director to take over Laurentian's School of Architecture". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Logan, Leanne; Cole, Geert (5 July 2001). New Caledonia. Lonely Planet. pp. 52–. ISBN 978-1-86450-202-2. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "Flèche faîtière de grande maison cérémonielle". musees.org/louvre (in French). Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "Kanak Fleche Faitiere". Sales arte.tv. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- The situation of Kanak people in New Caledonia, France. – Country Reports – UNSR James Anaya, page 8

- Lal, Brij V.; Fortune, Kate (2000). The Pacific Islands: an encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8248-2265-1. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Corciega, Rizalyn. "Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre" (PDF). Architecture.uwaterloo.ca/. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Irwin, Sean. "Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre Nouméa, New Caledonia" (PDF). Architecture.uwaterloo.ca. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Murphy, Bernice. "Centre Culturel Tjibaou" (PDF). Epress.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- "TanzerLongoria2007", p. 319

- aka vines

- Te Papa Museum of NZ. Wharepuni.

- Phillipps, William (1952). Maori houses and food stores (No. 8). RE Owen.

- Brown, Diedre. (2009). Maori Architecture: from fale to wharenui and beyond. Raupo, Penguin.

- John White The Ancient History of the Maori, His Mythology and Traditions. Volume V1 (1888). Pataka. Online at NZETC.

- Best, Elsdon. (1974, 1916). Maori storehouses and kindred structures, Wellington, Government Printer.

- Māori Architecture – from fale to wharenui and beyond. North Shore: Penguin Group. 2009. pp. 52–53. ISBN 9780143011125.

-

Hooper, Steven; Phelps, Steven (1976). Art and Artefacts of the Pacific, Africa and the Americas: The James Hooper Collection. Hutchinson [for Christie, Manson & Woods]. p. 25. ISBN 9780091250003. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

Barge boards (maihi) led up to the gable apex where either a carved head (koruru) or a complete figure (tekoteko [...]) representing a revered ancestor, was attached.

- Prickett, N. J. (1982). An archaeologist's guide to the Maori dwelling. New Zealand Journal of Archaeology, 4, pp. 111–147.

- "Māori Architecture - Advance magazine". Archived from the original on 2015-02-24. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- Mead (2003), pp 95–100, 215–6

- Thompson, R., 1998. Four Projects. Architectural Design, 68, pp.62–65.

- "Obituary: Rewi Thompson". Architectureau.com. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Elisapeta Heta". www.jasmax.com. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Elisapeta Heta - The University of Auckland". www.auckland.ac.nz. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Big Interview: Elisapeta Heta". www.diversityagenda.org. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- "Field Guide 2020: Keri Whaitiri". Design Assembly. 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "About | Kauri Architects". Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "Heralding her heritage". NZ Herald. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "I Te Timatanga / the beginning". Architecture Now. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- Kake, Jade. "Jade Kake". The Spinoff. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- Husband, Dale (2019-10-05). "Jade Kake: Māori by design". E-Tangata. Retrieved 2020-11-10.