Anonymous (2011 film)

Anonymous is a 2011 period drama film directed by Roland Emmerich[3] and written by John Orloff. The film is a fictionalized version of the life of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, an Elizabethan courtier, playwright, poet and patron of the arts, and suggests he was the actual author of William Shakespeare's plays.[4] It stars Rhys Ifans as de Vere and Vanessa Redgrave as Queen Elizabeth I of England.

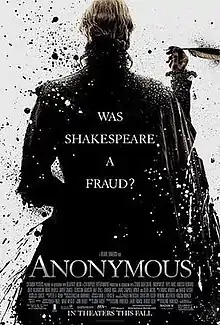

| Anonymous | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roland Emmerich |

| Written by | John Orloff |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Anna Foerster |

| Edited by | Peter R. Adam |

| Music by | |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Releasing |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 130 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[2] |

| Box office | $15.4 million[2] |

The film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11, 2011.[5] Produced by Centropolis Entertainment and Studio Babelsberg and distributed by Columbia Pictures, Anonymous was released on October 28, 2011 in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, expanding to theatres around the world in the following weeks. The film was a box office flop and received mixed reviews, with critics praising its performances and visual achievements, but criticising the film's time-jumping format, factual errors, and promotion of the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship.[6]

Plot

In modern-day New York, Derek Jacobi arrives at a theatre where he delivers a monologue questioning the lack of manuscript writings of William Shakespeare, despite the undeniable fact that he is the most performed playwright of all time. Ben Jonson is preparing to enter the stage. The narrator offers to take the viewers into a different story behind the origin of Shakespeare's plays: "one of quills and swords, of power and betrayal, of a stage conquered and a throne lost."

Jumping to Elizabethan London, Ben Jonson is running through the streets carrying a parcel and being pursued by soldiers. He enters the theatre called The Rose and hides the manuscripts he carries as the soldiers set fire to the theatre. Ben is detained at the Tower of London to face the questioning of puritanical Robert Cecil. The writings by Edward de Vere that Robert Cecil thought Ben had are not found on him.

In a flashback of five years, an adult Edward lives, disgraced and banished from court, in the last years of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. The queen is old and in failing health, but, as she has remained unmarried, lacks an heir. The elderly Lord William Cecil, the Queen's primary adviser, and his son Robert manage the kingdom's affairs. A growing group of malcontent nobles gather at court, led by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, who is widely believed to be Elizabeth's bastard son. The Cecils have secretly been planning to solve the succession crisis by offering the crown to Elizabeth's cousin, King James VI of Scotland; the idea of a foreign king inheriting the crown of the Tudors angers enough nobles that they begin to muster support for Essex to claim the throne when Elizabeth dies. Edward's young friend, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, is pledged to support Essex but Edward warns him against any rash action and that any move they make has to be managed carefully to avoid civil war.

When Edward and Henry visit a public theatre to see a play written by Ben Jonson, Edward witnesses how a play can sway people, and thinks that it can be used to thwart the influence of the Cecils, who as devout Puritans reject theatre as the 'worship of false idols', with Queen Elizabeth concerning her successor. After the Cecils declare Ben's play illegal and arrest him, Edward arranges for his release and instructs him to stage a play he wrote and act as the author. The play, Henry V, galvanizes the people and even Ben, who had contemptuously dismissed Edward's skill as a writer as the passing fancy of a bored nobleman, is impressed. At curtain call, however, William Shakespeare, an actor and "drunken oaf", steps forward to be recognized as the author of the play.

Elizabeth accepts a gift that evokes a memory from forty years before, when the boy, Edward, performed in his own play, A Midsummer Night's Dream, as Puck. After the elder Earl of Oxford's death, the teenage Edward is made a ″ward of court″ and entrusted to William Cecil and must write his plays secretly to avoid his guardian's ire. During this time, Edward kills a spying servant who had discovered his plays. William Cecil covers up the incident but forces Edward into a marriage with his daughter, Anne. However, Edward is infatuated with the queen and, after a brief time living on the continent, he begins an affair with Elizabeth. When the queen discovers she is pregnant with Edward's child, she tells William of her intention to marry him but he dissuades her and arranges for the child to be fostered into a noble family, as they had done in the past with Elizabeth's other bastards. Elizabeth ends her affair with Edward without telling him why. Angered, he has an affair with a lady-in-waiting to Elizabeth and learns from her that he had fathered a child with the queen. When Elizabeth learns of the affair, Edward is banished from court but not before learning the name of his illegitimate child: Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton.

Back in the adult Edward's time, despite Shakespeare's claim to his plays, Edward continues to provide Ben with plays which quickly become the thrill of London. Despite their unhappiness at the plays' popularity, the Cecils do not outlaw them because they fear the mob which might occur if they do. Ben becomes increasingly frustrated with his role as Edward's messenger and his own inability to match the brilliance of his plays. Later on, Shakespeare discovers that Edward is the real author and extorts him for money. He orders the construction of the Globe Theatre, where he bans Jonson's works from being performed, and claims Edward's plays as his own. Christopher Marlowe discovers Shakespeare's deal, and is later found with his throat slit. Jonson confronts Shakespeare and accuses him of murder. Edward and Essex, seeking to reduce Cecil's influence and to secure Essex's claim to succession, decide to force their way into the palace, against Cecil's wishes. Edward writes the play Richard III in order to incite hatred against Cecil and to summon a mob of Essex's supporters. Simultaneously, he would gain access to Elizabeth by sending her Venus and Adonis.

The plan is set to fail when a bitter Ben, angered by what he perceives as his own inadequacy as a writer and Shakespeare's unearned success, betrays the plan to Robert Cecil by informing him that Richard III will be played as a hunchback, a reference to Robert Cecil's own deformity. The mob is stopped at the Bridge, and Robert Devereux and Henry surrender in the palace courtyard when the soldiers fire on them from the parapet. Robert Cecil tells Edward that Elizabeth has had other illegitimate children, the first of whom was born during the reign of Bloody Mary when she was only sixteen and a virtual prisoner of her sister. William Cecil, already close to the future queen, hid the child and passed him off as the son of the Earl of Oxford, revealing Edward's parentage to him: he is the first of Elizabeth's bastard children. Horrified by the failure of his plan for the succession, the expected execution of his son and the knowledge that he committed incest with his own mother, Edward nevertheless visits the Queen in a private audience to beg her to spare Henry. Elizabeth agrees to spare Henry, but insists that Edward remain anonymous as the true author of "Shakespeare's" works. Henry is released while Essex is executed for his treason.

After Elizabeth's death, James of Scotland succeeds as James I of England and retains Robert Cecil as his primary adviser. On his deathbed, Edward entrusts a parcel full of his writings to Ben to keep them away from the royal family. Ben at first refuses the task and confesses to Edward that he betrayed him to the Cecils. In an unexpected heart-to-heart between the two playwrights, Edward admits that, whenever he had heard the applause for his plays, he had always known they were celebrating another man but that he had always wanted to gain Ben's approval, as he had been the only one to know that he had been the author of the plays. Ben admits that he considers Edward to be the 'Soul of the Age' and promises to protect the plays and publish them when the time is right.

After Edward's death, Ben's interrogation ends when Robert Cecil hears that the Rose has been destroyed by fire and he had hidden the plays inside. As he is released, Robert instructs Ben to better Edward and wipe his memory from the world. Ben tells him that he would if he could but that it was impossible to do. Miraculously, Ben finds the manuscripts where he hid them in the ruins of the Rose. At a performance of a "Shakespeare" play performed at court, James I remarks to a visibly unhappy Robert that he is an avid theatre goer.

Returning to the present day theatre, the narrator concludes the story by revealing the characters' fates: Robert Cecil remained the King's most trusted advisor, but never succeeded in banishing Edward's plays. Shakespeare did not remain in London, but returned to his hometown of Stratford upon Avon where he spent his last remaining years as a businessman. Ben would achieve his dream and became the first Poet Laureate, and would later write the introduction to the collected works purported to be authored by William Shakespeare. Although the story ends with the fate of its characters, the narrator proclaims that the poet who wrote these works, whether it be Shakespeare or another, had not seen the end of their story, and that "his monument is ever-living, made not of stone but of verse, and it shall be remembered ... as long as words are made of breath and breath of life."

Cast

- Rhys Ifans as Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

- Jamie Campbell Bower as young Oxford

- Vanessa Redgrave as Elizabeth I of England. Redgrave commented that "It's very interesting, the fractures, in this extraordinary creature. ... I only hope that I've been able to respond to Roland in this script sufficiently to be able to just give a little glimpse of this fracturing, this black hole, with shafts of brief sunlight."[7]

- Joely Richardson as young Queen Elizabeth (Richardson is Redgrave's daughter)

- Sebastian Armesto as Ben Jonson, poet and playwright

- Rafe Spall as William Shakespeare

- David Thewlis as William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, longtime adviser to Queen Elizabeth. Edward de Vere came to live in his household as a ″ward of the court″ at age 12 and as Earl of Oxford became Burghley's son-in-law at age 21. Burghley is portrayed in the film as the inspiration for the character Polonius.

- Edward Hogg as Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, William Cecil's son and successor

- Xavier Samuel as Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, dedicatee of Shakespeare's narrative poems and possible focus of his sonnets and, in this movie, the illegitimate son of Edward de Vere and Elizabeth

- Sam Reid as Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, executed for treason

- Paolo De Vita as Francesco, servant to the Earl of Oxford

- Trystan Gravelle as Christopher "Kit" Marlowe, poet and dramatist

- Robert Emms as Thomas Dekker, dramatist

- Tony Way as Thomas Nashe, poet and satirist

- Alex Hassell as Gabriel Spenser

- Mark Rylance as actor Henry Condell playing narrator/chorus (Henry V) and Richard III

- John Keogh as Philip Henslowe

- Helen Baxendale as Anne de Vere

- Amy Kwolek as young Anne de Vere

- Lloyd Hutchinson as Richard Burbage

- Vicky Krieps as Beassie Vavasour

- Derek Jacobi as narrator

Production

Background and development

Screenwriter John Orloff (Band of Brothers, A Mighty Heart) became interested in the authorship debate after watching a 1989 Frontline programme about the controversy.[8] He penned his first draft in the late 1990s, but commercial interest waned after Shakespeare in Love was released in 1998.[9] It was almost green lit as The Soul of the Age for a 2005 release, with a budget of $30 to $35 million. However, financing proved to be "a risky undertaking", according to director Roland Emmerich. In October 2009, Emmerich stated, "It's very hard to get a movie like this made, and I want to make it in a certain way. I've actually had this project for eight years."[10] At a press conference at Studio Babelsberg on April 29, 2010, Emmerich noted that the success of his more commercial films made this one possible, and that he got the cast he wanted without the pressure to come up with "at least two A-list American actors."[11]

Emmerich noted he knew little of either Elizabethan history or the authorship question until he came across John Orloff's script, after which he "steeped" himself in the various theories.[12][13][14] Wary of similarities with Amadeus, Emmerich decided to recast it as a film on the politics of succession and the monarchy, a tragedy about kings, queens and princes, with broad plot lines including murder, illegitimacy and incest – "all the elements of a Shakespeare play."[15]

In a November 2009 interview, Emmerich said the heart of the movie is in the original title The Soul of the Age, and it revolved around three main characters: Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, and the Earl of Oxford. In a subsequent announcement in 2010, Emmerich detailed the finalised plot line:[16]

It's a mix of a lot of things: it's an historical thriller because it's about who will succeed Queen Elizabeth and the struggle of the people who want to have a hand in it. It's the Tudors on one side and the Cecils on the other, and in between [the two] is the Queen. Through that story we tell how the plays written by the Earl of Oxford ended up labelled "William Shakespeare".

Filming

Anonymous was the first motion picture to be shot with the Arri Alexa camera, with most of the period backgrounds created and enhanced via new CGI technology.[17] In addition, Elizabethan London was recreated for the film with more than 70 painstakingly hand-built sets at Germany's Studio Babelsberg, including a full-scale replica of London's imposing The Rose theatre.

Reception

Critical response

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 45% of 177 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 5.5/10. The website's consensus reads: "Roland Emmerich delivers his trademark visual and emotional bombast, but the more Anonymous stops and tries to convince the audience of its half-baked theory, the less convincing it becomes."[18] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 50 out of 100, based on 43 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[19] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A–" on an A+ to F scale.[20]

Rex Reed regards Anonymous as "one of the most exciting on-screen literary rows since Norman Mailer was beaten with a hammer", and well worth the stamina required to sit out what is an otherwise exhausting film. Not only Shakespeare's identity, but also that of Queen Elizabeth, the "Virgin Queen" is challenged by Orloff's script, which has her as "a randy piece of work who had many lovers and bore several children." Visually, the film gives us a "dazzling panorama of Tudor history" which will not bore viewers. It boasts a cast of pure gold, and its "recreation of the Old Globe, the fame that brought ruin and dishonour to both Oxford and the money-grubbing Shakespeare, and the sacrifice of Oxford's own property and family fortune to write plays he believed in against a background of danger and violence make for a bloody good yarn, masterfully told, lushly appointed, slavishly researched and brilliantly acted." He adds the caveats that it does play "hopscotch with history", has a bewildering and confusing cast of characters and is jumpy in its timeframes.[21]

Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune writes that the film is ridiculous but not dull. Displaying a "rollicking belief in its own nutty bombast" as "history is simultaneously being made up and rewritten", its best scenes are those of the candle-lit interiors caught by the Alexa digital camera on a lovely copper-and-honey-toned palette. After a week, what remains in Phillips' memory is not the de Vere/Shakespeare conspiracy theory but "the way Redgrave gazes out a window, her reign near the end, her eyes full of regret but also of fiery defiance of the balderdash lapping at her feet."[22]

Roger Ebert finds Orloff's screenplay "ingenious", Emmerich's direction "precise", and the cast "memorable". Though "profoundly mistaken", Anonymous is "a marvellous historical film", giving viewers "a splendid experience: the dialogue, the acting, the depiction of London, the lust, jealousy and intrigue." However, Ebert stated he must "tiresomely insist that Edward de Vere did not write Shakespeare's plays."[23]

Kirk Honeycutt of The Hollywood Reporter ranked it as Emmerich's best film, with a superb cast of British actors, and a stunning digitally-enhanced recreation of London in Elizabethan times. The film is "glorious fun as it grows increasingly implausible", for the plot "is all historical rubbish".[24] Damon Wise, reviewing the film for The Guardian, appraises Emmerich's "meticulously crafted" and "stunningly designed takedown of the Bard", as shocking only in that it is rather good. Emmerich's problem, he argues, is that he was so intent on proving his credentials as a serious director that the film ended up "drowned in exposition". Orloff's screenplay heavily confuses plotlines; the politics are retrofitted to suit the theory. The lead roles are "unengaging" but special mention is given to Edward Hogg's performance as Robert Cecil, and Vanessa Redgrave's role as Elizabeth.[25]

Robert Koehler of Variety reads the film as an "illustrated argument" of an "aggressively promoted and more frequently debunked" theory, and finds it less interesting than the actors who play a role in, or endorse, it. Narrative cogency is strained by the constant switches in time signature, and the imbroglio of Shakespeare and Jonson squabbling publicly over claims to authorship is both tiresome and "veers close to comedy"; indeed it is superfluous given Ifans's commanding and convincing acting as the "real" Shakespeare. The supporting cast of actors is praised for fine performances, except for Spall's Shakespeare, who is "often so ridiculous that the 'Stratfordians' will feel doubly insulted." Sebastian Krawinkel's "ambitious and gorgeous production design" comes in for special mention, as does Anna J. Foerster's elegant widescreen lensing. The score, however, fails their standards.[26]

David Denby of The New Yorker writes of Emmerich's "preposterous fantasia", where confusion reigns as to which of the virgin queen's illegitimate children is Essex and which Southampton, and where it is not clear what the connection is between the plot to hide the authorship of the plays and the struggle to find a successor to the officially childless Elizabeth. He concludes that, "The Oxford theory is ridiculous, yet the filmmakers go all the way with it, producing endless scenes of indecipherable court intrigue in dark, smoky rooms, and a fashion show of ruffs, farthingales, and halberds. The more far-fetched the idea, it seems, the more strenuous the effort to pass it off as authentic."[27]

James Lileks of Star Tribune, noting favourable responses, including one where a critic wondered if Emmerich had anything to do with it, says the devious message must be that a shlock-merchant like Emmerich wasn't involved, but, like the film plot itself, must conceal the hand of some more experienced filmmaker, whose identity will be much debated for centuries to come.[28] Reviewing for Associated Press, Christy Lemire commends Rhys Ifans' performance as "flamboyant, funny, sexy" in an otherwise heavy-handed and clumsy film, whose script "jumps back and forth in time so quickly and without rhyme or reason, it convolutes the narrative." A "flow chart" is perhaps needed to keep track of all of the sons, and sons of sons. The "blubbering" about the brilliance of Shakespeare's works is repetitive, and upstages the initial whiff of scandal, giving the impression that the film is "much ado about nothing".[29]

A. O. Scott of The New York Times wrote that Anonymous is "a vulgar prank on the English literary tradition, a travesty of British history and a brutal insult to the human imagination". Yet, a fine cast manages to "burnish even meretricious nonsense with craft and conviction", and one is "tempted to suspend disbelief, even if Mr. Emmerich finally makes it impossible."[30] Lou Lumenick, writing for the New York Post, writes that the movie "is a thoroughly entertaining load of eye candy with solid performances, even if John Orloff's exposition-heavy script practically requires a concordance to follow at times."[31] For The Globe and Mail's Liam Lacey, "the less you know about Shakespeare, the more you're likely to enjoy Anonymous." Ingenuity is wasted on an "unintelligent enterprise", that of arguing that people of humble origins cannot outwrite blue-bloods. Emmerich's CGI effects are well-done, but it is amazing just to watch an "actor on a bare wooden stage, using nothing but a sequence of words that make your scalp prickle."[32]

Box office

Anonymous was originally slated for worldwide release in a Shakespeare in Love-style opening, but was rescheduled for restricted release on 28 October 2011 in 265 theatres in the United States, Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom, expanding to 513 screens in its second week.[33] Pre-release surveys had predicted a weak opening weekend (under $5 million), leading Sony to stagger release dates and depend on word-of-mouth to support a more gradual release strategy (as they did with Company Town). According to Brendan Bettinger, "Anonymous came out of Toronto with surprisingly positive early reviews for a Roland Emmerich picture." Sony distribution president Rory Bruer said, "We love the picture and think it's going to get great word of mouth. We're committed to expanding it until it plays wide."[34] In the end, the film was a "box office disaster,"[35] bringing in US $15.4 million at the box office against a budget of $30 million.[2]

Accolades

Anonymous was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Costume Design for German Costume Designer Lisy Christl's work,[36] but lost to Best Picture winner The Artist.[37] That same year, it was also nominated for 7 Lolas, winning in 6 Categories including Best Cinematography for Anna J. Foerster, Best Art Direction for Stephan O. Gessler and Sebastian T. Krawinkel and Best Costume Design for Lisy Christl. At the Satellite Awards, the film was nominated in two categories including Best Art Direction (and Production Design) for Stephan O. Gessler and Sebastian T. Krawinkel, and Best Costume Design for Lisy Christl.[38] Vanessa Redgrave was nominated for Best British Actress of the Year at the London Film Critics Circle Awards for Anonymous and Coriolanus.[39] The film also received a nomination from the Art Directors Guild for Period Film, honouring Production designer Sebastian T. Krawinkel[40] and two nominations from the Visual Effects Society in the categories of Outstanding Supporting Visual Effects in a Feature Motion Picture and Outstanding Created Environment in a Live Action Feature Motion Picture.[41]

Controversy

Pre-release arguments

In a trailer for the movie, Emmerich lists ten reasons why in his view Shakespeare did not write the plays attributed to him.[42] Other plans envisaged the release of a documentary about the Shakespeare authorship question, and providing materials for teachers. According to Sony Pictures, "The objective for our Anonymous program, as stated in the classroom literature, is 'to encourage critical thinking by challenging students to examine the theories about the authorship of Shakespeare's works and to formulate their own opinions.' The study guide does not state that Edward de Vere is the writer of Shakespeare's work, but it does pose the authorship question which has been debated by scholars for decades".[43] In response, on September 1, 2011, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust launched a programme to debunk conspiracy theories about Shakespeare, mounting an Internet video in which 60 scholars and writers reply to common queries and doubts about Shakespeare's identity for one minute each.[44][45] In Shakespeare's home county of Warwickshire, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust promoted a protest against the film by temporarily covering or crossing out Shakespeare's image or name on pub signs and road signs.[46]

Columbia University's James Shapiro, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal[47] noted that according to an article in the same journal in 2009, three U.S. Supreme Court Justices now lent support to the Oxfordian theory, whereas in a moot court judgment in 1987, Justices John Paul Stevens, Harry Blackmun and William Brennan had "ruled unanimously in favor of Shakespeare and against the Earl of Oxford."[48][49] "The attraction of these ideas owes something to the Internet, where conspiracy theories proliferate", he argued, adding that "Emmerich's film is one more sign that conspiracy theories about the authorship of Shakespeare's plays have gone mainstream". Scriptwriter John Orloff replied that Shapiro oversimplified the facts, since Justice Stevens later affirmed that he had had "lingering concerns" and "gnawing doubts" that Shakespeare might have been someone else, and that if the author was not Shakespeare, then there was a high probability he was Edward de Vere.[50]

Emmerich complains of what he sees as the "arrogance of the literary establishment" to say: "We know it, we teach it, so shut the fuck up." He has singled out James Shapiro, an expert on these theories, as a member of that establishment, accusing him of being a liar:

He [Shapiro] ... sometimes claims certain things which then I then [sic] as a scholar cannot dispute, but later I check on it and find out he was totally lying. Just outright lying. It's bizarre. But they also have a lot to lose. He wrote a bestseller about William Shakespeare called "1599" which is one year in the life of this mine [sic] which is incredible to read when you all of a sudden realize where did he get all of this stuff from?[51]

Expectations

Emmerich is on record as believing that "everybody in the Stratfordian side is so pissed off because we've called them on their lies."[52] Shapiro believes that while supporters of de Vere's candidacy as the author of Shakespeare's plays have awaited this film with excitement, in his view, they may live to regret it.[53] Robert McCrum in The Guardian wrote that the Internet is the natural home of conspiracy theories; therefore, the Oxford case, "a conspiracy theory in doublet and hose with a vengeance", means that Anonymous, irrespective of its merits or lack of them, will usher in an "open season for every denomination of literary fanatic."[54]

Screenwriter John Orloff argued that the film would reshape the way we read Shakespeare.[8] Derek Jacobi said that making the film was "a very risky thing to do", and imagines that "the orthodox Stratfordians are going to be apoplectic with rage."[55]

Bert Fields, a lawyer who wrote a book about the authorship issue, thinks scholars may be missing the larger benefit that Anonymous provides – widespread appreciation of the Bard's work. "Why do these academics feel threatened by this? It isn't threatening anybody", Fields commented. "The movie does things that I don't necessarily agree with. But if anything, it makes the work more important. It focuses attention on the most important body of work in the English language."[43]

Fictional drama

In an interview with The Atlantic, scriptwriter John Orloff was asked, "In crafting your characters and the narrative, how were you able to find the right balance between historical fact, fiction, and speculation?" Orloff responded, "Ultimately, Shakespeare himself was our guide. The Shakespeare histories are not really histories. They're dramas. He compresses time. He adds characters that have been dead by the time the events are occurring. He'll invent characters out of whole cloth, like Falstaff in the history plays. First and foremost it's a drama, and just like Shakespeare we're creating drama."

Emmerich, when given examples of details that do not correspond to the facts, was reported as being more concerned with the mood of the film. He agreed that there were many historical mistakes in his film, but said movies have a right to do this, citing Amadeus. Emmerich also notes that Shakespeare was not concerned with historical accuracy, and argues that examining the inner truth of history was his objective.[56]

Crace, in discussing the notion of Emmerich as a "literary detective", comments that the director "has never knowingly let the facts get in the way of a good story."[14] Historian Simon Schama called the film 'inadvertently comic', and said of its thesis that the real problem was not so much the "idiotic misunderstanding of history and the world of the theater", but rather the "fatal lack of imagination on the subject of the imagination."[57] James Shapiro wrote that it is a film for our time, "in which claims based on conviction are as valid as those based on hard evidence", which ingeniously circumvents objections that there is not a scrap of documentary evidence for de Vere's authorship by assuming a conspiracy to suppress the truth. The result is that "the very absence of surviving evidence proves the case."[53]

Tiffany Stern, professor of early modern drama at Oxford University, says that the film is fictional, and should be enjoyed as such. Gordon McMullan, professor of English at King's College, says Shakespeare wrote the plays, and the idea he didn't is related to a conspiracy theory that coincides with the emergence of the detective genre. For Orloff, criticisms by scholars that call the film fictional rather than factual are kneejerk reactions to the "academic subversion of normality".[43]

Historical accuracy

In a pre-release interview, scriptwriter Orloff said that, with the exception of whether Shakespeare wrote the plays or not, "The movie is unbelievably historically accurate ... What I mean by that is that I, like Henry James, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Derek Jacobi and John Gielgud, don't think Shakespeare wrote the plays, but obviously a lot more people do think Shakespeare wrote the plays. Obviously, in my movie, he didn't, so a lot of people will say that's not historically accurate and they are totally welcome to that opinion. But, the world within the movie, that that story takes place in, is incredibly accurate, like the Essex Rebellion and the ages of the characters."

Orloff also described the attention given to creating a "real London", noting that the effects crew "took 30,000 pictures in England, of every Tudor building they could find, and then they scanned them all into the computer and built real London in 1600."[58]

According to Holger Syme,[59] Stephen Marche[60] and James Shapiro,[61] the film does contain a number of historical inaccuracies. These include standard theatrical techniques such as time compression and the conflating of supporting characters and locations, as well as larger deviations from recorded history.

Succession to Elizabeth

Essex was King James of Scotland's most avid supporter in England during the closing years of Elizabeth's reign.[61] The film presents James as the Cecils' candidate, and Essex as a threat to his succession. In fact William Cecil feared James, believing he bore a grudge against him for his role in the death of James' mother, Mary Queen of Scots.[61]

Plays and poems

The film redates some plays and poems to fit the story of the 1601 Essex Rebellion. Most significantly, it was Richard II that was performed on the eve of Essex's uprising, not Richard III.[59] Richard III is advertised as brand-new in 1601, written for the uprising, when in fact it was printed four years earlier in 1597.[59] The crowd watching Richard III swarms out of the theatre towards the court, but are gunned down on Cecil's orders. This event never occurred.[61] The poem Venus and Adonis is presented as a "hot-off-the-press bestseller" written and printed by de Vere especially for the ageing Queen in 1601 to encourage her to support Essex. It was published in 1593.

The film also shows the first production of a play by the Earl of Oxford, credited to Shakespeare, as being Henry V – although in reality that play is a sequel, completing the stories of several characters introduced in Henry IV Part I and Henry IV Part II. Later, Macbeth is shown being staged after Julius Caesar and before Richard III and Hamlet, though those plays are estimated by scholars to have been performed around 1593 and 1600–1601 respectively[62] whereas Macbeth, often called "the Scottish play" because of its Scottish setting and plot, is generally believed to have been written to commemorate the ascent of the Scottish King James to the English throne. That did not happen until 1603.[63] However, because the film uses non-linear storytelling, this may not necessarily be an inaccuracy so much as a montage of plays performed at the Globe and a tribute to the extensive list of works that comprise the Shakespeare canon, with order not being relevant.

The history of Elizabethan drama is altered to portray de Vere as an innovator. Jonson is amazed to learn that Romeo and Juliet, written in 1598, is apparently entirely in blank verse. The play actually appeared in print in 1597,[59] and Gorboduc precedes it as the first to employ the measure throughout the play by more than 35 years. By 1598 the form was standard in theatre; however, Jonson's shock may have been in reference to the fact that De Vere in particular would be capable of writing a play in iambic pentameter, and not to the idea that one could be written.[59] The film also portrays A Midsummer Night's Dream as composed by De Vere in his childhood, approximately 1560. It was written several decades later; however, the film does imply that De Vere wrote many plays and hid them from the public for decades before having Shakespeare perform them, so this does not necessarily contradict the timeline of the play being first performed on the London stage in public between 1590 and 1597, as is the traditional belief.[60][64]

Early in the film, Jonson is arrested for writing a "seditious" play. This is based on the fact that in 1597 he was arrested for sedition as co-writer of the play The Isle of Dogs with Thomas Nashe, possibly his earliest work.[65] The text of the play does not survive.[66] He was eventually released without charge. The "seditious" play in the film is referred to by the name "Every Man". Jonson did write plays called Every Man in His Humour and Every Man Out of His Humour. The fragments of dialogue we hear are from the latter. Neither were deemed seditious.

Other departures from fact

The death of Christopher Marlowe plays a small but significant role in the storyline. Marlowe is portrayed alive in 1598, while in fact he died in 1593.[59] The slashing of Marlowe's throat occurs in Southwark with Shakespeare as his suggested murderer, whereas Marlowe was killed by Ingram Frizer with a knife stab above the left eye, in Deptford.[59] Marlowe is shown mocking Dekker's Shoemaker's Holiday in 1598, although it was not written until the following year.[59] Marlowe appears in the film to die on the same day that Essex departs for Ireland; however, this juxtaposition of scenes may simply be non-linear storytelling rather than a historical error, as the events are not related in the film whatsoever. These events actually happened six years apart.[60] Another writer shown to be alive after his death is Thomas Nashe, who appears in a scene set after 1601. He is known to have died by that year, though the exact date is uncertain.[59]

Other departures for dramatic effect include the portrayal of Elizabeth's funeral taking place on the frozen Thames. The actual ceremony took place on land. The Thames did not freeze over that year. Oxford's wife, Anne Cecil, died in 1588, and he remarried in 1591. The film conflates his two wives into the character of Anne.[56] The film shows a theatre burning down in 1603. It appears to be The Rose, which was never recorded as having caught fire, whereas the real Globe Theatre burned down in 1613 when explosions during a performance accidentally set it alight.[59]

De Vere is shown pruning a rose bush, which he describes as a rare Tudor rose. The Tudor rose was not a real biological plant, but a graphic device used by the Tudor family; however, De Vere may have been speaking metaphorically.[67]

See also

References

- British Board of Film Classification 2011

- "Anonymous (2011)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- Secret Defence: Roland Emmerich's "Anonymous" on Notebook|MUBI

- May 1980, p. 9

- Evans, Ian (2011). "Anonymous premiere – 36th Toronto International Film Festival". DigitalHit.com. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Robert Sawyer,'Biographical Aftershocks: Shakespeare and Marlowe in the Wake of 9/11', in Critical Survey, Berghahn publishers, Volume 25, Number 1 (Spring) 2013 pp. 19–32, p. 28: 'While the rivalry with Marlowe is not a central feature of the movie, wild conjecture is. As Douglas Lanier has recently posited, the movie displays a 'pile-up of factual errors', borrowing more from a long 'list of intercinematic' references rather than any reliance on 'fidelity to the verifiable historical record'.

- Nepales 2010

- Leblanc 2011.

- Screen Daily 2004.

- Elfman 2009.

- Youtube 2010.

- Salisbury 2010

- Malvern 2011.

- Crace 2011.

- Chavez 2009.

- De Semlyen, Phil (February 25, 2010). "Exclusive: Emmerich On Anonymous". Empire.

- de Semlyen 2010.

- "Anonymous". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- "Anonymous". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- Finke, Nikki (October 29, 2011). "Snow Ices Box Office: 'Puss In Boots' #1, 'Paranormal' #2, 'In Time' #3, 'Rum Diary' #4". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- Reed 2011.

- Phillips 2011.

- Ebert 2011.

- Honeycutt 2011.

- Wise (1) 2011.

- Koehler, Robert (September 10, 2011). "Anonymous". Variety.

- Denby 2011

- Lileks 2011.

- Lemire 2011.

- Scott (1) 2011

- Lumenick 2011.

- Lacey 2011.

- "Weekend Box Office Results for August 25–27, 2017 - Box Office Mojo". boxofficemojo.com.

- Brendan Bettinger, Collider

- Paul Edmondson, Stanley Wells, Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy, Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 161.

- "Nominees for the 84th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- The Artist Wins Costume Design: 2012 Oscars on YouTube

- "2011 Winners". International Press Academy. December 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- Child, Ben (December 20, 2011). "Scandinavian directors lead Drive for London Film Critics' Circle awards". The Guardian. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- Kilday, Gregg (January 3, 2012). "Art Directors Nominate Movies as Different as 'Harry Potter' and 'The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 15, 2012.

- "10th Annual VES Awards". visual effects society. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- Emmerich 2011.

- Lee (1) 2011.

- Blogging Shakespeare 2011.

- Smith 2011

- Child 2011.

- Alter 2010

- Bravin 2009.

- Brennan, Blackmun & Stevens 2009.

- Orloff 2010.

- Lee (2) 2011.

- AFP 2011.

- Shapiro (1) 2011.

- McCrum 2011.

- Horwitz 2010.

- Wise (2) 2011.

- Schama 2011.

- "Anonymous Screenwriter John Orloff Exclusive Interview". Collider. September 22, 2010. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Syme 2011

- Marche 2011

- Shapiro (2) 2011.

- "The Chronology of Shakespeare's Plays". Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- "Anonymous (2011): Class, Conspiracy, and Shakespeare". February 26, 2012.

- Edmondson & Wells 2011, p. 30.

- John Paul Rollert, A Failure of Will, The Point

- David Riggs, Ben Jonson: A Life, Harvard University Press, 1989, p. 32.

- Penn, Thomas (2011). Winter King: Henry VII and the Dawn of Tudor England. Simon & Schuster. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4391-9156-9.

Footnotes

- AFP (September 14, 2011). "Shakespeare fans will hate Anonymous". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- Alter, Alexandra (April 9, 2010). "The Shakespeare Whodunit: A Scholar Tackles Doubters on Who Wrote the Plays;Hollywood Weighs In". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Asay, Paul (October 29, 2011). "Anonymous". Plugged In Online. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Biancolli, Amy (October 29, 2009). "Plenty of poetic license in 'Anonymous'". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- Blogging Shakespeare (August 2011). "The Shakespeare Whodunit: Sixty Minutes with Shakespeare". Blogging Shakespeare.com. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Bravin, Jess (April 18, 2009). "Justice Stevens Renders an Opinion on Who Wrote Shakespeare's Plays: It Wasn't the Bard of Avon, He Says; 'Evidence Is Beyond a Reasonable Doubt". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Brennan, William J.; Blackmun, Harry; Stevens, John Paul (2009). "Who Wrote Shakespeare moot-court debate at American University". Frontline. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- British Board of Film Classification (August 26, 2011). "Anonymous (12A)". Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- Caranicas, Peter (April 12, 2011). "Lensers focus on digital fave Alexa". Variety. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Chase, Andrea (October 28, 2011). "Anonymous Movie Review". Killer Movie Reviews. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- Chavez, Kelvin (November 11, 2009). "With Roland Emmerich". Latino Review Online. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- Child, Ben (2011). "Shakespeare film Anonymous has lost plot, says Stratford". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- Crace, John (June 16, 2011). "The unreasonable doubt of Roland Emmerich's Anonymous". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- Denby, David (October 31, 2011). "All That Glitters". New Yorker. p. 2. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- de Semlyen, Phil (February 25, 2010). "Roland Emmerich's Next Is 'Anonymous' About Shakespeare". Empire Online. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Dujsik, Mark (October 27, 2011). "ANONYMOUS (2011)". Mark Reviews Movies.com. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Elfman, Mali (October 9, 2009). "Roland Emmerich on His Shakespeare Film". Screen Crave. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- Ebert, Roger (October 26, 2011). "Anonymous". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Edmondson, Paul; Wells, Stanley (2011). Shakespeare bites back: not so anonymous. Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- Ellwood, Gregory (September 11, 2011). "Roland Emmerich's 'Anonymous' is just plain silly". HitFix. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Emmerich, Roland (October 16, 2011). "Ten Reasons why Shakspeare was a fraud". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Emmerich, Roland (April 2010). "Press Conference". Youtube. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Fritz, Ben; Horn, John (October 19, 2011). "'Anonymous' won't open nationwide in last-minute change". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Goldberg, Matt (September 14, 2010). "Sony Pushes Roland Emmerich's ANONYMOUS Back to Fall 2011". Collider. Archived from the original on December 7, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Honeycutt, Kirk (September 9, 2011). "Roland Emmerich brings Shakespeare's London to vivid life in this early 17th century conspiracy theory with a large and superb British cast". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Hopkins, Lisa (2005). Beginning Shakespeare. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6423-4. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Hornaday, Ann (October 28, 2011). "A literary conspiracy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 29, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Horwitz, Jane (June 9, 2010). "Backstage: What the stars had to get over to get their 'Goat' on at Rep Stage". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Howell, Peter (October 27, 2011). "Anonymous: To be or not to believe". Toronto Star. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Hilsman, Hoyt (October 27, 2011). "Backstage: What the stars had to get over to get their 'Goat' on at Rep Stage". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Jones, Melanie (October 27, 2011). "'Anonymous' Movie's Shakespeare Fraud: Class Snobbery, Centuries Late". International Business Times. Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Kaufman, Amy (October 27, 2011). "Movie Projector: 'Puss in Boots' to stomp on competition". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Keller, Louise (October 27, 2011). "Anonymous Review". Urban Cinefile. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Kohn, Eric (October 25, 2011). "In "Anonymous", Roland Emmerich Revises Shakespeare; We Advise You Wait For Joss Whedon". indieWire. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- Lacey, Liam (October 28, 2011). "Anonymous. A Shakespearean Whodunit". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Leblanc, Beth (October 10, 2011). "Emmerich film sparks debate". The Michigan Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Lee (1), Chris (October 17, 2011). "Was Shakespeare a Fraud?". Newsweek. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Lee (2), Youyoung (October 27, 2011). "Q&A with 'Anonymous' Director Roland Emmerich". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- Lemire, Christy (October 26, 2011). "'Anonymous' is much ado about nothing". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Lileks, James (October 20, 2011). "This movie's so good they've cancelled the wide release". Star Tribune. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Lumenick, Lou (October 28, 2011). "Not so in love with this Shakespeare". New York Post. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Lybarger, Dan (October 28, 2011). "Should this film remain Anonymous= A review in iambic pentameter". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- Malvern, Jack (June 7, 2011). "Oldest literary conspiracy theory trotted out again". The Australian. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Marche, Stephen (October 21, 2011). "Wouldn't It Be Cool if Shakespeare Wasn't Shakespeare?". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- May, Steven W. (1980). Studies in Philology, The Poems of Edward DeVere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford and of Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex. Vol. 77. University of North Carolina Press.

- McCrum, Robert (June 8, 2011). "Anonymous set to propel Edward de Vere to stardom". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- Medley, Tony (October 29, 2011). "Anonymous". The Tolucan Times. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Metacritic (October 29, 2011). "Anonymous Reviews". CBS Interactive. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Nepales, Janet Susan (May 16, 2010). "Hollywood Bulletin – Love Notes from Verona". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- Nicholson, Amy (October 5, 2011). "'Anonymous' Review". Boxoffice. Archived from the original on October 24, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- Noveck, Jocelyn (October 27, 2011). "New Shakespeare film ruffles academic feathers". Associated Press. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Orloff, John (April 19, 2010). "The Shakespeare Authorship Question Isn't Settled". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- Pandya, Gitesh (October 30, 2011). "Box Office Guru! Puss in Boots at Top with $34M". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- Pappamichael, Stella (October 24, 2011). "'Anonymous' review – London Film Festival 2011". Digital Spy. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- Pereira, Kevin; Emmerich, Roland (October 20, 2011). "Roland Emmerich on Directing Anonymous". g4tv.com. Event occurs at 4.45–6. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- Phillips, Michael (October 27, 2011). "Elizabethan lit intrigue proves not that intriguing in 'Anonymous' – 2 1/2 stars". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Pols, Mary F. (October 26, 2011). "Anonymous: So Shakespeare Was a Fraud? Really?". Time. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Rastogi, Nina (April 7, 2011). "First Glimpse of "Anonymous", Roland Emmerich's Loony Take on the Shakespeare Debate". Slate. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- Ray, William (July 23, 2011). "Roland Emmerich's "Anonymous" Explores A Different Kind Of Conspiracy/comment". Film Fan Review. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- Reed, Rex (October 25, 2011). "Anonymous Gives the Mystery of Who Wrote Shakespeare's Plays A Very Good Name". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on October 29, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Rosenbaum, Ron (2006). The Shakespeare wars: clashing scholars, public fiascoes, palace coups. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50339-9. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- Rosenbaum, Ron (October 27, 2011). "10 Things I Hate About Anonymous". Slate. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Rotten Tomatoes. "Anonymous (2011)". Flixster. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- Sachs, Ben (October 28, 2011). "Anonymous". Chicago Reader. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- Salisbury, Mark (June 14, 2010). "On the set of Roland Emmerich's Anonymous". Time Out. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- Schama, Simon (October 17, 2011). "The Shakespeare Shakedown". Newsweek. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Scott (1), A. O. (October 27, 2011). "How Could a Commoner Write Such Great Plays?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Scott (2), Mike (October 29, 2011). "'Anonymous' review: Film takes up debate on Shakespeare authorship question". Nola.com. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- Screen Daily (May 11, 2004). "Emmerich vs. Shakespeare! Independence Day Meets St. Crispin's Day". Screen Daily. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- Shapiro, James (April 11, 2010). "Alas, Poor Shakespeare". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Shapiro (1), James (October 17, 2011). "Hollywood Dishonors the Bard". The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- Shapiro (2), James (November 4, 2011). "Shakespeare – a fraud? Anonymous is ridiculous". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- Smith, Alistair (September 1, 2011). "Shakespeare Birthplace Trust launches authorship campaign". The Stage. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- Stevens, Dana (May 4, 2010). "Das Junket". Slate. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- Stevens, Dana (October 27, 2011). "Anonymous:The problem with this Shakespeare-conspiracy movie is that it wasn't dumb enough". Slate. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Syme, Holger (September 19, 2011). "People Being Stupid About Shakesp… or Someone Else". Dispositio. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- Tapley, Kristopher (September 9, 2011). "Emmerich surprises with 'Anonymous'". InContention.com. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- Turner, Michael (October 26, 2011). "Anonymous". View London. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- Weber, Bill (October 27, 2011). "Anonymous". Slant Magazine. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- Whitfield, Ed (October 25, 2011). "Much Ado about Nothing". The Ooh Tray. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- Whitty, Stephen (October 28, 2011). "To see or not to see". Newark Star-Ledger. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- Wise (1), Damon (September 10, 2011). "The shock in this exposé of the Bard is that it is rather good". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Wise (2), Damon (October 27, 2011). "Roland Emmerich: Appetite for deconstruction". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- Zacharek, Stephanie (September 9, 2011). "Even Killer Elite Can't Quite Outduel Emmerich's Anonymous". Movieline. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

External links

- Official website

- Anonymous at IMDb

- Anonymous at AllMovie

- Anonymous at Box Office Mojo

- Anonymous at Rotten Tomatoes

- Anonymous at Metacritic

- Anonymous trailer on YouTube

- April 29, 2010 Press Conference on YouTube (partial; see other linked clips)

- Shakespeare's Lost Kingdom: The True History of Shakespeare and Elizabeth (book supported by the filmmakers)

- Brows Held High's Kyle Kallgren take on the 2011 film on YouTube