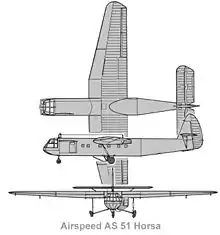

Airspeed Horsa

The Airspeed AS.51 Horsa was a British troop-carrying glider used during the Second World War. It was developed and manufactured by Airspeed Limited, alongside various subcontractors; the type was named after Horsa, the legendary 5th-century conqueror of southern Britain.

| AS.51 and AS.58 Horsa | |

|---|---|

| |

| An Airspeed Horsa under tow | |

| Role | Troop and cargo military glider |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Airspeed Ltd |

| First flight | 12 September 1941 |

| Introduction | 1941 |

| Status | retired |

| Primary users | Army Air Corps United States Army Air Forces, Royal Canadian Air Force, Indian Air Force |

| Number built | 3,799 |

Having been greatly impressed by the effective use of airborne operations by Germany during the early stages of the Second World War, such as during the Battle of France, the Allied powers sought to establish capable counterpart forces of their own. The British War Office, determining that the role of gliders would be an essential component of such airborne forces, proceeded to examine available options. An evaluation of the General Aircraft Hotspur found it to lack the necessary size, thus Specification X.26/40 was issued. It was from this specification that Airspeed Limited designed the Horsa, a large glider capable of accommodating up to 30 fully equipped troops, which was designated as the AS 51.

The Horsa was used in large numbers by the British Army Air Corps and the Royal Air Force (RAF); both services used it to conduct various air assault operations through the conflict. The type was used to perform an unsuccessful attack on the German Heavy Water Plant at Rjukan in Norway, known as Operation Freshman, and during the invasion of Sicily, known as Operation Husky. Large numbers of Horsa were subsequently used during the opening stages of the Battle of Normandy, being used in the British Operation Tonga and American operations. It was also deployed in quantity during Operation Dragoon, Operation Market Garden, and Operation Varsity. Further use of the Horsa was made by various other armed forces, including the United States Army Air Forces.

Development

Background

In the early stages of the Second World War, the German military demonstrated its role as a pioneer in the deployment of airborne operations. These forces had conducted several successful operations during the Battle of France in 1940, including the use of glider-borne troops during the Battle of Fort Eben-Emael.[1][2] Having been impressed by the performance and capabilities of German airborne operations, the Allied governments decided that they would also form their own airborne formation.[3] As a result of this decision, the creation of two British airborne divisions came about, as well as a number of smaller-scale units.[4] On 22 June 1940, the British airborne establishment was formally initiated when the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, directed the War Office in a memorandum to investigate the possibility of creating a corps of 5,000 parachute troops.[5] During 1941, the United States also embarked on a similar programme.[6]

While the equipment for the airborne forces was under development, it was decided by War Office officials that gliders would be an integral component of such a force. It was initially thought that gliders would be used to deliver paratroops. Transport aircraft would both carry paratroops and tow a glider with a second party of troops. The idea arose as a response to the severe shortage of transport aircraft in the early part of the war, as in this way the number of troops that could be dropped in an operation by a given number of transport aircraft would be greatly enhanced. The empty gliders would be towed back to base.[7]

However, thinking eventually evolved into using gliders to land both troops and heavy equipment in the theatre of operations.[8] The first glider produced was the General Aircraft Hotspur, which first flew on 5 November 1940.[9] Several problems were found with the Hotspur's design, the worst being its inability to carry sufficient troops. It was believed that airborne troops should be landed in larger groups than the eight that the Hotspur could carry, and that the number of towplanes required would prove to be impractical. There were also concerns that the gliders would have to be towed in tandem, which would be extremely hazardous at night or through cloud.[10]

Accordingly, it was decided that the Hotspur would be used only as a training glider,[11] while British industry continued with the development of several different gliders, including a larger 25-seater assault glider, which would become the Airspeed Horsa.[10] On 12 October 1940, Specification X.26/40 was issued, calling for a large assault glider.[12] The specification required the use of wood where possible to conserve critical supplies of metal.[13] Airspeed would designate the Horsa the AS.51.[12]

.. it must have been the most wooden aircraft ever built. Even the controls in the cockpit were masterpieces of the woodworker's skill.

— H. A. Taylor, Mrazek 1977, pg. 70

Airspeed assembled a team headed by aircraft designer Hessell Tiltman[13][14] whose efforts began at the de Havilland technical school at Hatfield, Hertfordshire, before relocating to Salisbury Hall, London Colney.[13] The Horsa was to have had paratroopers jumping from doors on either side of the fuselage, while the glider remained under tow, while combat landings would have been secondary. The widely set doors enabled simultaneous egress, as well as for troops to fire on nearby enemies while still in the glider. For this they were provided with several firing points in the roof and tail.[13] That idea was dropped, and it was decided to just have the glider land troops.[15]

Production

In February 1941, an initial order was placed for 400 gliders and it was estimated that Airspeed should be able to complete the order by July 1942.[16] Early on, inquiries were made into the possibility of a further 400 being manufactured in India for the use of Indian airborne forces, however, this plan was abandoned when it was discovered the required wood would have to be imported into India.[16] Seven prototypes were ordered with Fairey Aircraft producing the first two prototypes, which were used for flight testing, while Airspeed completed the remaining prototypes that were used in equipment and loading tests.[6][13] On 12 September 1941, the first prototype (DG597), towed by an Armstrong Whitworth Whitley,[17] made its first flight,[18] 11 months after the specification was issued.[15]

As specified in Specification X3/41, 200 AS 52 Horsas were also to be constructed to carry bombs. A central fuselage bomb bay holding four 2,000 lb (910 kg) or two 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) bombs was fitted into the standard Horsa fuselage. The concept of towing bombs was dropped as other bombers became available, resulting in the order for the AS 52 being cancelled.[18]

In early 1942, production of the Horsa commenced; by May 1942, some 2,345 had been ordered by the Army for use in future airborne operations.[15] The glider was designed from the outset to be constructed using components and a series of 30 sub-assemblies required to complete the manufacturing process.[6] Manufacturing was intended primarily to use woodcrafting facilities, which were not needed for more urgent aviation production, and as a result, production was spread across separate factories, which consequently limited the likely loss in case of German attack.[10] The designer A. H. Tiltman said that the Horsa "went from the drawing board to the air in ten months, which was not too bad considering the drawings had to be made suitable for the furniture trade who were responsible for all production."

The initial 695 gliders were manufactured at Airspeed's factory in Christchurch, Hampshire;[17] production of the remainder was performed by an assortment of subcontractors.[15] These included Austin Motors, and a production group coordinated by the furniture manufacturers Harris Lebus.[19] These same contractors would produce an improved model of the glider, designated as the AS.53 Horsa Mk II, while none would be manufactured by Airspeed themselves. The Horsa Mk II had been specifically designed for the carriage of vehicles, featuring a reinforced floor and a hinged nose section in order to accommodate such use. Other changes included the adoption of a twin nosewheel arrangement, a modified tow attachment and an increased all-up weight of 15,750 lb (7,140 kg).

As a consequence of the majority of subcontractors not having available airfields from which to deliver the gliders, they sent the sub-assemblies to RAF Maintenance Units (MUs), who would perform final assembly themselves; this process has been attributed as being responsible for the widely varying production numbers recorded of the type.[15] Between 3,655 and 3,799 Horsas had been completed by the time production ended.[N 2]

Design

The Airspeed AS.51 Horsa was a large troop-carrying glider. It was capable of transporting a maximum of 30 seated fully equipped troops; it also had the flexibility to carry a Jeep or an Ordnance QF 6-pounder anti-tank gun.[22] The Horsa Mark I had a wingspan of 88 feet (27 m) and a length of 67 feet (20 m), and when fully loaded weighed 15,250 lb (6,920 kg).[23][24] The later AS 58 Horsa II featured an increased fully loaded weight of 15,750 lb (7,140 kg) along with a hinged nose section, reinforced floor and double nose wheels to support the extra weight of vehicles.[2] The tow cable was attached to the nose wheel strut, rather than the dual wing points of the Horsa I. The Horsa was composed largely of wood; it was described by aviation author H. A. Taylor as being: "the most wooden aircraft ever built. Even the controls in the cockpit were masterpieces of the woodworker's skill".[24]

It was considered to be sturdy and very manoeuvrable for a glider. The design of the Horsa adopted a high-wing cantilever monoplane configuration, being equipped with wooden wings and a wooden semi-monocoque fuselage. The fuselage was built in three sections bolted together, the front section held the pilot's compartment and main freight loading door, the middle section was accommodation for troops or freight, the rear section supported the tail unit.[25]

The fuselage joint at the rear end of the main section could be broken on landing to facilitate the rapid unloading of troops and equipment, for which ramps were provided.[22] Initially the tail was severed by detonating a ring of Cordtex around the rear fuselage. But this was thought to be hazardous, especially if detonated prematurely by enemy fire.[26] In early 1944, a method of detaching the tail was devised that used eight quick-release bolts, and wire-cutters to sever the control cables.[24]

The wing carried large "barn door" flaps which, when lowered, made a steep, high rate-of-descent landing possible—this performance would allow the pilots to land in constricted spaces.[24] By employing a combination of the flaps and pneumatic brakes, the glider could be brought to a stop within relatively short distances.[24] The Horsa was equipped with a fixed tricycle landing gear and it was one of the first gliders equipped with a tricycle undercarriage for take off. On operational flights, the main gear could be jettisoned and landing was then made on the castoring nose wheel and a sprung skid set on the underside of the fuselage.[25][2]

The pilot's compartment had two side-by-side seats and dual controls, all of which being contained within a large Plexiglas nose section.[13] Initially, the cockpit would be outfitted with internal telephone systems that allowed for communication between the pilots of the glider and tug aircraft while connected; however, this was replaced on later-built models by radio sets instead, which had the advantage of being able to maintain contact after detaching.[24] Aft of the pilot's compartment was the freight loading door on the port side; the hinged door could also be used as a loading ramp.[24] The main compartment could accommodate 15 troops on benches along the sides with another access door on the starboard side. Supply containers could also be fitted under the centre-section of the wing, three on each side.

During March 1942, the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment and 1st Airlanding Brigade commenced loading trials using several of the prototypes, but immediately ran into problems. During an attempt to load a jeep into a prototype, Airspeed personnel present informed the evaluation staff that to do so would break the glider's loading ramp, as it had been designed to hold only a single motorbike. With this lesson learnt, 1st Airlanding Brigade subsequently began sending samples of all equipment required to go into Horsas to Airspeed, and a number of weeks were spent ascertaining the methods and modifications required to fit the equipment into a Horsa.[27] Even so, the loading ramp continued to be considered to be fragile and prone to damage, which would ground the glider if sustained during loading.[24]

Operational history

Wartime use

The Horsa was first deployed operationally on the night of 19/20 November 1942 in the unsuccessful attack on the German Heavy Water Plant at Rjukan in Norway (Operation Freshman). The two Horsa gliders, each carrying 15 sappers, and one of the Halifax tug aircraft crashed in Norway due to bad weather. All 23 survivors from the glider crashes were executed on the orders of Adolf Hitler, in a flagrant breach of the Geneva Convention which protects prisoners of war (POWs) from summary execution.[17]

In preparation for further operational deployment, 30 Horsa gliders were air-towed by Halifax bombers from bases in Great Britain to North Africa; three of these aircraft were lost in transit.[20] On 10 July 1943, the 27 surviving Horsas were used during Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, which was the type's first large-scale operation.[2]

The Horsa was deployed in large numbers (estimated to be in excess of 250) during Battle of Normandy; specifically in the British Operation Tonga and the American airborne landings in Normandy. The first unit to land in France during the battle was a British coup-de-main force, carried by six Horsas, that captured the Caen canal and Orne river bridges. During the opening phase of the operation, 320 Horsas were used to perform the first lift of the 6th Airborne Division, while a further 296 Horsas participated in the second lift.[17] Large numbers of both American and British forces were deployed using the Horsa during the opening phase of the battle.[28]

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) acquired approximately 400 Horsas in a form of reverse Lend-Lease.[25][28] Capable of accommodating up to 30 troop seats,[25] the Horsa was much bigger than the 13-troop American Waco CG-4A (known as the Hadrian by the British), and thus offered greater carrying capacity.[28][2]

In British service, the Horsa was a major component during several major offensives that followed the successful Normandy landings, such as Operation Dragoon and Operation Market Garden, both in 1944, and Operation Varsity during March 1945. The latter was the final operation for the Horsa, and had involved a force of 440 gliders carrying soldiers of the 6th Airborne Division across the Rhine.[17][2]

Operationally, the Horsa was towed by various aircraft: four-engined heavy bombers displaced from operational service such as the Short Stirling and Handley Page Halifax, the Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle and Armstrong Whitworth Whitley twin-engined bombers, as well as the US Douglas C-47 Skytrain/Dakota (not as often due to the weight of the glider).[29] In Operation Market Garden, however, a total of 1,336 C-47s along with 340 Stirlings were employed to tow 1,205 gliders,[30]) and Curtiss C-46 Commando. The gliders were towed with a harness that attached to points on both wings and also carried an intercom between tug and glider. The glider pilots were usually from the Glider Pilot Regiment, part of the Army Air Corps (AAC), although Royal Air Force (RAF) pilots were used on occasion.[20]

Postwar use

A small number of Horsa Mk IIs were obtained by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and participated in evaluation trials which were held at CFB Gimli, Manitoba. Three of these survivors were purchased as surplus in the early 1950s and ended up in Matlock, Manitoba, where they were scrapped.[31] India also acquired a small number of Horsas for their own evaluation purposes.[29] Due to low surplus prices in the UK, many were bought and converted to travel trailers and vacation cottages.[32]

On 5 June 2004, as part of the 60th anniversary commemoration of D-Day, Prince Charles unveiled a replica Horsa on the site of the first landing at Pegasus Bridge and talked with Jim Wallwork, the first pilot to land the aircraft on French soil during D-Day.

Ten replicas were built for the 1977 film A Bridge Too Far, mainly for static display and set-dressing, although one Horsa was modified to make a brief "hop" towed behind a Dakota at Deelen, the Netherlands. During the production, seven of the replicas were damaged in a wind storm; the contingent were repaired in time for use in the film. Five of the Horsa "film models" were destroyed during filming with the survivors sold as a lot to John Hawke, aircraft collector in the UK.[33] Another mock-up for close-up work came into the possession of the Ridgeway Military & Aviation Research Group and is stored at Welford, Berkshire.[34]

Variants

- AS.51 Horsa I

- Production glider with cable attachment points at upper attachment points of main landing gear.[14]

- AS.52 Horsa

- Bomb-carrying Horsa; project cancelled prior to design/production

- AS.53 Horsa

- further development of the Horsa not taken up.

- AS.58 Horsa II

- Development of the Horsa I with hinged nose, to allow direct loading and unloading of equipment, twin nose wheel and cable attachment on nose wheel strut.[14]

Operators

Surviving aircraft

An Airspeed Horsa Mark II (KJ351) is preserved at the Museum of Army Flying in Hampshire, England.[35] The Assault Glider Trust built a replica at RAF Shawbury using templates made from original components found scattered over various European battlefields and using plans supplied by BAE Systems (on the condition that the glider must not be flown[36]).[37] The replica was completed in 2014 and then stored at RAF Cosford until it was transferred to the Oorlogsmuseum in Overloon, the Netherlands in June 2019.[38]

A fuselage section displayed at the Traces of War museum at Wolfheze, Netherlands, was retrieved from Cholsey, Oxfordshire, where it had served as a dwelling for over 50 years. It was recovered around 2001 by the de Havilland Aircraft Museum, of London Colney, where it was stored until being bought by museum owner Paul Hendriks. The airframe is believed not to have seen active service. A cockpit section is on display at the Silent Wings Museum in Lubbock, Texas.

BAPC.232 Horsa I/II Composite – Nose & Fuselage sections is on display in the Walter Goldsmith Hangar at the de Havilland Aircraft Museum. A full-sized replica stands close to Pegasus Bridge, Normandy, as part of the Memorial Pegasus museum.

Specifications (AS.58 Mark II)

Data from Fighting Gliders of World War II,[39] British Warplanes of World War II,[40] BAE Systems

General characteristics

- Crew: Two

- Capacity: 28 troops / 2x ¼ton trucks / 1x M3A1 Howitzer + ¼ton truck with ammunition and crew / (20–25 troops was the "standard" Mark I load)[17]

- Length: 67 ft 0 in (20.42 m)

- Wingspan: 88 ft 0 in (26.82 m)

- Height: 19 ft 6 in (5.94 m)

- Wing area: 1,104 sq ft (102.6 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 7.2

- Airfoil: root: NACA 4419R 3.1; tip: NACA 4415R 3.1[41]

- Empty weight: 8,370 lb (3,797 kg)

- Gross weight: 15,750 lb (7,144 kg)

Performance

- Cruise speed: 100 mph (160 km/h, 87 kn) normal operational gliding speed

- Aero-tow speed: 150–160 mph (130–139 kn; 241–257 km/h)

- Stall speed: 48 mph (77 km/h, 42 kn) flaps down

- 58 mph (50 kn; 93 km/h) flaps up

- Wing loading: 14 lb/sq ft (68 kg/m2)

Notable appearances in media

See also

| External video | |

|---|---|

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- Black and yellow diagonal bands on the underside warn "I am towing or being towed" so other aircraft would stay clear of the towline, and that the aircraft was unable to freely manoeuvre.

- Precise figures for the total number of Horsas produced varies between sources. Aviation author David Mondey gives the figure of 3,799,[20] while Keith Flint and Tim Lynch give the number of 3,655,[15][21]

Citations

- Flanagan 2002, p. 6.

- Fredriksen 2001, p. 14.

- Harclerode 2005, p. 197.

- Harclerode 2005, p. 107.

- Otway 1990, p. 21.

- Mondey 2002, p. 14.

- Manion 2008, p.28

- Flint 2006, p. 15.

- Lynch 2008, p. 31.

- Smith 1992, p. 13.

- Otway 1990, p. 23.

- Flint 2006, p. 35.

- Mrazek 2011, p. 331.

- Mrazek 1977, pg. 70.

- Flint 2006, p. 56.

- Smith 1992, p. 14.

- Thetford 1968, p. 588.

- Bowyer 1976, p. 37.

- Lloyd 1982, p. 22.

- Mondey 2002, p. 15.

- Lynch 2008, p. 203.

- Morgan 2014, p. 59.

- Smith 1992, p. 15.

- Mrazek 2011, p. 336.

- Munson 1972, p. 169.

- Manion (2008), p.33

- Otway 1990, p. 57.

- Morgan 2014, p. 50.

- Swanborough 1997, p. 7.

- Morrison 1999, p. 56.

- Milberry 1984, p. 197.

- "Glider Cottage." Popular Mechanics, October 1947, p. 134.

- Hurst 1977, p. 29.

- "The Ridgeway Military & Aviation Research Group." freeuk.net, Retrieved: 27 July 2009.

- "The Collection." Archived 8 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Airborne Museum, Retrieved: 20 May 2009.

- Note; to enable the aircraft to be flown would require the UK CAA to issue a 'Permit to Fly' for the aircraft which would require the manufacturer (the now BAE Systems) to provide manufacturer support for the 70+ year old design. Due to age of the design and legal liability issues this is not now possible.

- Jenkins, T.N. "Horsa Replica – Full Background" Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Assault Glider Trust. Retrieved: 7 June 2009.

- "Horsa heads for the Netherlands". Aeroplane. Vol. 47, no. 8. August 2019. pp. 8–9. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Mrazek, James E. (1 January 1977). Fighting Gliders of World War II (1st ed.). London: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-28927-0.

- March 1998, p. 8.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Bishop, Chris. The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II: The Comprehensive Guide to Over 1,500 Weapons Systems, Including Tanks, Small Arms, Warplanes, Artillery, Ships and Submarines. New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2002. ISBN 1-58663-762-2.

- Bowyer, Michael J.F. "Enter the Horsa" (Army-air colours 1937–45). Airfix magazine, Volume 18, No. 1, September 1976.

- Dahl, Per F. Heavy Water and the Wartime Race for Nuclear Energy. London: CRC Press, 1999. ISBN 1-84415-736-9.

- Dank, Milton. The Glider Gang: An Eyewitness History of World War II Glider Combat. London: Cassel, 1977. ISBN 0-304-30014-4.

- Dover, Major Victor. The Sky Generals. London: Cassell, 1981. ISBN 0-304-30480-8.

- Flanagan, E. M. Jr. Airborne: A Combat History of American Airborne Forces. New York: The Random House Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 0-89141-688-9.

- Flint, Keith. Airborne Armour: Tetrarch, Locust, Hamilcar and the 6th Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment 1938–1950. Solihull, W. Midlands, UK: Helion & Company Ltd, 2006. ISBN 1-874622-37-X.

- Fredriksen, John C. International Warbirds: An Illustrated Guide to World Military Aircraft, 1914–2000. ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-364-5.

- Harclerode, Peter. Wings of War: Airborne Warfare 1918–1945. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005. ISBN 0-304-36730-3.

- Hurst, Ken. "Een Brug Te Fer: Filming with Dakotas." Control Column (Official organ of the British Aircraft Preservation Council), Volume 11, no. 2, February/March 1977.

- Knightly, James. "Airpeed Horsa Pilot." Aeroplane, Vol. 37, no. 8, August 2009.

- Lloyd, Alan. The Gliders: The Story of Britain's Fighting Gliders and the Men who Flew Them. London: Corgi, 1982. ISBN 0-552-12167-3.

- Lynch, Tim. Silent Skies: Gliders at War 1939–1945. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Military, 2008. ISBN 0-7503-0633-5.

- Manion, Milton (June 2008). Gliders of World War II:" The Bastards No One Wanted" (PDF) (Thesis). Air University, School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, Maxwell AFB, AL. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 March 2017.

- March, Daniel J. British Warplanes of World War II. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-874023-92-1.

- Morgan, Martin K. A. The Americans on D-Day: A Photographic History of the Normandy Invasion. MBI Publishing, 2014. ISBN 1-62788-154-9.

- Milberry, Larry, ed. Sixty Years: The RCAF and CF Air Command 1924–1984. Toronto: Canav Books, 1984. ISBN 0-9690703-4-9.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to British Aircraft of World War II. London: Chancellor Press, 2002. ISBN 1-85152-668-4.

- Morrison, Alexander. Silent Invader: A Glider Pilot's Story of the Invasion of Europe in World War II' (Airlife Classics). Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife, 1999. ISBN 978-1-84037-368-4.

- Mrazek, James E. (1977). Fighting Gliders of WWII. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-7091-5083-0 – via Internet Archive.

- Mrazek, James E. Airborne Combat: The Glider War/Fighting Gliders of WWII. Stackpole Books, 2011. ISBN 0-81174-466-3.

- Munson, Kenneth. Aircraft of World War II. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1972. ISBN 0-385-07122-1.

- Otway, Lieutenant-Colonel T.B.H. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army: Airborne Forces. London: Imperial War Museum, 1990. ISBN 0-901627-57-7.

- Reinders, Philip. The Horsa MkI, Arnhem and Modification Record Plates. Philip Reinders, 2012.

- Saunders, Hilary St. George. The Red Beret: The Story of the Parachute Regiment, 1940–1945. London: White Lion Publishers Ltd, 1972. ISBN 0-85617-823-3.

- Smith, Claude. History of the Glider Pilot Regiment. London: Pen & Sword Aviation, 1992. ISBN 1-84415-626-5.

- Swanborough, Gordon. British Aircraft at War, 1939–1945. East Sussex, UK: HPC Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-9531421-0-8.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force 1918–57. London: Putnam, 1968. ISBN 0-370-00101-X.

- Walburgh Schmidt, H. No Return Flight, 13 Platoon at Arnhem 1944. Soesterberg, Netherlands, Uitgeverij Aspekt. ISBN 978-90-5911-881-2.