Adelaide I, Abbess of Quedlinburg

Adelaide I (German: Adelheid; 973/74[lower-alpha 1] – 14 January 1044 or 1045), a member of the royal Ottonian dynasty was the second Princess-abbess of Quedlinburg from 999, and Abbess of Gernrode from 1014, and Abbess of Gandersheim from 1039 until her death, as well as a highly influential kingmaker of medieval Germany.[3]

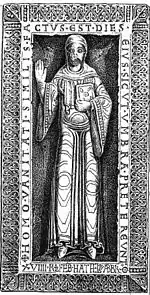

| Adelaide I | |

|---|---|

Tombstone | |

| Princess-abbess of Quedlinburg | |

| Reign | 999 – 14 January 1044 or 1045 |

| Predecessor | Matilda |

| Successor | Beatrice I |

| Born | 973/74 |

| Died | 14 January 1044 or 1045 Quedlinburg Abbey |

| Burial | |

| Dynasty | Ottonian |

| Father | Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Theophanu |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Early life

Named after her paternal grandmother, Queen Adelaide of Italy, Abbess Adelaide was the eldest daughter of Emperor Otto II and his consort Theophanu. She was educated in Quedlinburg Abbey by her paternal aunt, Abbess Matilda. While Matilda and Theophanu stayed at the Italian court of Pavia in 984, the young girl was abducted by the forces of her quarrelling uncle Duke Henry II of Bavaria in 984 and held in custody by his henchman, the Billung count Egbert the One-Eyed. Soon after, however, she was released by loyal Saxon troops.

In October 995 Adelaide became a canoness in Quedlinburg. When Abbess Matilda died on 7 February 999, she was elected her successor and consecrated on Michaelmas (September 28) by Bishop Arnulf of Halberstadt.

Influencing the royal and imperial elections

In the German royal election of 1002 after the death of her brother Emperor Otto III, Adelaide and her older sister, Abbess Sophia of Gandersheim, acted as true kingmakers, having rejected Margrave Eckard of Meissen (who discounted their influence) as candidate for kingship. Together with Sophia, Adelaide significantly influenced the election of her cousin Henry II as King of the Romans. Henry vested Quedlinburg Abbey with extended estates and in 1014 entrusted Adelaide with the administration of the convents in Gernrode, Frose and Vreden in Westphalia. He repeatedly celebrated important feasts at Quedlinburg and in 1021 attended the consecration of the St Servatius Collegiate Church together with Archbishop Gero of Magdeburg.

The Princess-Abbess and her sister would play the same role in the election of Henry's Salian successor King Conrad II as Holy Roman Emperor in 1027. Nonetheless, when Sophia died on 27 January 1039, Conrad II at first denied Adelaide's request to succeed her as abbess of Gandersheim. Upon his death later in that year, King Henry III eventually granted her the right to rule Gandersheim too.[3][4]

Death

Adelaide died either on 14 January 1044 or on 14 January 1045 and was succeeded by her kinswoman, Beatrice of Franconia. She is buried in Quedlinburg Abbey. A lifesized tomb marker preserves the conventional image of Adelaide. She is represented as holy woman by monastic habit and Gospel book. In fact, the image depicts what Adelaide represented rather than Adelaide herself.[5]

Notes

- The birth of a daughter of "Ottoni inperatori et Theophanu auguste...quam nominee matris sue imperatricis insignivit" is recorded in the Annalista Saxo in 977,[1] but this appears incorrect assuming that the approximate birth dates of her sisters Sophie and Mathilde are correct and that Adelheid was her parents' oldest daughter as recorded by Thietmar, who also confirmed that she became a nun at Quedlinburg.[2]

References

- Annalista Saxo Cronica 977, Pertz, G. H. (ed.) Monumenta Germaniæ Historica Scriptorum VI, pp. 542-777, Leipzig 1828, 1925.

- Thietmari Chronicon 4.10, p. 158, Pertz, G. H. (ed.) Monumenta Germaniæ Historica Scriptorum III, pp. 723-871, Hannover 1839, 1925.

- Wolfram; Kaiser, Herwig; Denise Adele (2006). Conrad II, 990-1039: emperor of three kingdoms. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-02738-X. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bernhardt, John W. (2002). Itinerant Kingship and Royal Monasteries in Early Medieval Germany, C.936-1075. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52183-1. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- Mitchell, Linda Elizabeth (1999). Women in medieval western European culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8153-2461-8. Retrieved 2009-07-08.