A Traveler from Altruria

A Traveler from Altruria is a Utopian novel by William Dean Howells. It was first published in installments in The Cosmopolitan between November 1892 and October 1893, and eventually in book form by Harper & Brothers in 1894. The novel is a critique of unfettered capitalism and its consequences, and of the Gilded Age.

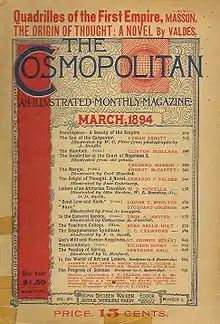

Vol. XVI, No.5 (the March 1894 issue) of The Cosmopolitan, which contained Howells's "Letters of an Altrurian Traveller" | |

| Author | William Dean Howells |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Utopian novel |

| Publisher | Harper & Brothers |

Publication date | 1894 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 318 pp |

Introduction

Set during the early 1890s in a fashionable summer resort somewhere on the East Coast of the United States, the book is narrated by a Mr Twelvemough, a popular author of light fiction who has been selected to function as host to a visitor from the faraway island of Altruria called Mr Homos. Homos has come all the way to the United States to experience first-hand everyday life in the country which prides itself to represent democracy and equality, to see for himself how the principle that "all men are created equal" is being practiced.

However, due to Altruria's secluded existence very little is known about that state, so Twelvemough and his circle of acquaintances, all of whom are staying at the same hotel, are more eager to learn something about Altruria than to explain American life and institutions. To their dismay, it becomes gradually clear to everyone involved in the conversations with Mr Homos—who in the course of the novel becomes less and less reluctant to talk about his own country—that the United States is greatly lagging behind Altruria in practically every aspect of life, be it political, economical, cultural, or moral. Thus, in the novel the island state of Altruria serves as a foil to America, whose citizens, compared to Altrurians, appear selfish, obsessed with money, and emotionally imbalanced. Mainly, A Traveller from Altruria is a critique of unfettered capitalism and its consequences, and of the Gilded Age in particular.

In A Traveler from Altruria, Howells acknowledges the history of Utopian literature by having his group of educated characters refer to eminent representatives of that literary tradition such as Campanella (La città del Sole, 1602) and Francis Bacon (New Atlantis, 1623), but also to quite recent authors like Edward Bellamy (Looking Backward, 1888) and William Morris (News from Nowhere, 1890). "With all those imaginary commonwealths to draw upon, from Plato, through More, Bacon, and Campanella, down to Bellamy and Morris, he has constructed the shakiest effigy ever made of old clothes stuffed with straw," says the professor, one of Homos's discussion partners, to his fellow Americans. "Depend upon it, the man is a humbug. He is not an Altrurian at all."

Publication

The novel was first published in installments in The Cosmopolitan, Vol. XIV, No.1 (November 1892) to Vol. XV, No.6 (October 1893), and eventually in book form by Harper & Brothers in 1894.

Title

"Altruria" derives from the Latin alter "the other". As opposed to egotism, altruism—a word coined during the first half of the 19th century by Auguste Comte—is unselfish concern for the welfare of others. Thus, Altruria is a Utopian country inhabited exclusively by altruists, by people who believe that they have a moral obligation to help, serve, or benefit others, if necessary by the sacrifice of self interest.

Class distinctions and the gap between rich and poor

The social differences in America are shown by having the rich of the society staying at a luxurious resort near the farms of workers in a lower class. Howells admits that the farmers are not fit to associate with those at the resort because their manners are not good enough. This story is dealing with social protest. According to Twelvemough, the successful people become wealthy or powerful because of "their talents, their shrewdness, their ability to seize an advantage and turn it into their own account."

Right from the first moment of his stay at the fashionable summer hotel it becomes evident that Mr Homos's behaviour is fundamentally different from that of the other guests. He insists on carrying his own luggage, at busy times helps waiters in the restaurant do their job, and chats easily with employees, which makes him rather popular among them but at the same time embarrasses his host:

It was quite impossible to keep him from bowing with the greatest deference to our waitress; he shook hands with the head-waiter every morning as well as with me; there was a fearful story current in the house, that he had been seen running down one of the corridors to relieve a chambermaid laden with two heavy water-pails which she was carrying to the rooms to fill up the pitchers. This was probably not true; but I myself saw him helping in the hotel hay-field one afternoon, shirt-sleeved like any of the hired men. He said that it was the best possible exercise, and that he was ashamed he could give no better excuse for it than the fact that without something of the kind he should suffer from indigestion. It was grotesque, and out of all keeping with a man of his cultivation and breeding. He was a gentleman and a scholar, there was no denying, and yet he did things in contravention of good form at every opportunity, and nothing I could say had any effect with him. (Ch. X)

Homos further points out that he considers it strange if people perform exercise in order to stay fit if all they would have to do is participate in manual labour. By doing so, they would at the same time relieve the burden of those who regularly work with their hands. ("To us, exercise for exercise would appear stupid. The barren expenditure of force that began and ended in itself, and produced nothing, we should—if you will excuse my saying so—look upon as childish, if not insane or immoral.")

Generally, Homos is surprised to find that neither Mr Twelvemough, the novelist, nor any of his acquaintances—a professor, a businessman, a manufacturer, a banker, and a clergyman—has any social relations whatsoever to people from the working classes or to any of the country people who permanently live in the area where they themselves just spend a few weeks each summer. The only contact Mrs Makely, the businessman's wife, can claim is occasional charitable visits to an old country woman now confined to her bed. At one point even the minister ruefully admits that there are no manual labourers in his congregation ("I suppose they have their own churches").

Homos draws the conclusion that Americans differentiate between political and economic equality, noting that they may have the former but that they certainly do not enjoy the latter.

In Howells' writing he focuses not only on the social injustices but also the economic injustices in society. There is an obvious dissatisfaction with society, yet he still approves of the society as a whole. Howells makes it clear that Altruria's society is better than America's because of its lack of money and class. The belief is that if men acknowledge their commonalities and work for each other, they will dispense with differences of rank and class. He believes that men should treat each other as equals. There is a need for reforms.

Money and the world of work

In Altruria, which is an explicitly Christian country, money has been abolished, so its inhabitants have even forgotten that there used to be a division between rich and poor. Every citizen is entitled to everything they need at any given time, so there is no need, and actually no way, to save for a rainy day, while amassing a fortune is impossible as well. Physical labour is shared amongst the working population so that no one has to work for more than three hours per day. Also, there is no need to hurry so that craftsmanship flourishes and every finished product resembles a work of art. By common consent, cheap and faulty merchandise such as the "Saturday night shoe" is no longer produced.

Whereas in Altruria there is no such thing as workers' exploitation, the American banker explains to Homos how business is done in the United States:

The first lesson of business, and the last, is to use other men's gifts and powers. If he looks about him at all, he sees that no man gets rich simply by his own labor, no matter how mighty a genius he is, and that, if you want to get rich, you must make other men work for you, and pay you for the privilege of doing so.(Ch. VIII)

The banker then adds that, as an entrepreneur, working "for the profit of all" (as suggested by Homos) rather than working for one's own profit would be "contrary to the American spirit. It is alien to our love of individuality". Anyone who wants to be successful in this world will try to do so by getting rich. As a reaction to this, Homos just points out that in Altruria, excellence is achieved by excellently serving others.

When talking about American workers, the worker

"is dependent upon the employer for his chance to earn a living, and he is never sure of this. He may be thrown out of work by his employer's disfavor or disaster, and his willingness to work goes for nothing; there is no public provision of work for him; there is nothing to keep him from want, nor the prospect of anything" (p. 66)

Problems with American society in the 1890s

The purpose of a Utopia is potentially to fix the problems that are current in society. It is clear that Howells was well aware of the issues with Americas society at the time of this story. The Altruria Utopia is what he felt was an ideal society. American society at this time seemed too concerned with money. Howells describes the people of the society as being selfish and materialistic. At this time in America money and power was causing constant struggle for those of the working class. In Altruria, money is not a problem because there is not any. Every man is equal. Every man works. It seems to be a good way of life, however, it does not seem very realistic. As Mrs. Makely says, "There must be rich and there must be poor. There always have been, and there always will be" [149–150]. Howells method to fix that thought is the Altrurian system where everyone is guaranteed a share of the national product only if he works at least three hours a day in an acceptable occupation.

Opportunity in Altruria

In an attempt to rid the struggle for money, Howells makes Altruria a place with none. The only way to get what is needed is to work for it. Therefore, there is an opportunity for everyone. In the United States, opportunity usually comes from money. Opportunity usually comes from associations and people that are involved with money. In Altruria, anyone can have an opportunity if they want it.

Discussion

David W. Levy has indicated that in A Traveler from Altruria Howells, while pursuing his industrious, profitable career as a man of letters, criticized the business principles that had helped ensure his own success. However, Levy also suggests that Howells, rather than solely romanticizing the poor at the expense of the middle and upper classes, created characters that represent "two sides of Howells' own personality", with the narrator embodying Howells' personal ambition and the altruist his aspiration toward a greater common good.

Consequences

Inspired by the Utopian ideas expressed in A Traveler from Altruria, in 1894 Unitarian minister Edward Biron Payne and thirty of his followers founded Altruria, a short-lived Utopian community in Sonoma County, California.

Howells would eventually create an Altrurian trilogy, following the first book with Letters of an Altrurian Traveller (1904) and Through the Eye of the Needle (1907).

Release details

- A Traveler from Altruria, ed. with an Introduction by David W. Levy (1996) (ISBN 978-0-312-11799-3).

References

- Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers. p. 154.

- Alberto Manguel & Gianni Guadalupi: The Dictionary of Imaginary Places (Toronto, 1980), s.v. "Altruria".

External links

- A Traveler from Altruria at Project Gutenberg

A Traveller from Altruria public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A Traveller from Altruria public domain audiobook at LibriVox- "A Traveller from Altruria", a poem by Florence Earle Coates. (also published as "The Singer")