ALDH7A1

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family, member A1, also known as ALDH7A1 or antiquitin, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ALDH7A1 gene.[5] The protein encoded by this gene is a member of subfamily 7 in the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. These enzymes are thought to play a major role in the detoxification of aldehydes generated by alcohol metabolism and lipid peroxidation. This particular member has homology to a previously described protein from the green garden pea, the 26g pea turgor protein. It is also involved in lysine catabolism that is known to occur in the mitochondrial matrix. Recent reports show that this protein is found both in the cytosol and the mitochondria, and the two forms likely arise from the use of alternative translation initiation sites. An additional variant encoding a different isoform has also been found for this gene. Mutations in this gene are associated with pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy. Several related pseudogenes have also been identified.[6]

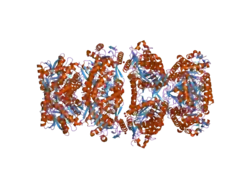

Structure

The protein encoded by this gene can localize to the cytosol, mitochondria, or nucleus depending on the inclusion of certain localization sequences. The N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence is responsible for mitochondrial localization, while the nuclear localization signal and nuclear export signal are necessary for nuclear localization. Exclusion of the above in the final protein product leads to cytosolic localization. In the protein, two amino acid residues, Glu121 and Arg301, are attributed for the binding and catalyzing one of its substrates, alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde (α-AASA).[7]

Antiquitin shares 60% homology with the 26g pea turgor protein, also referred to as ALDH7B1, in the green garden pea.[8]

Function

As a member of subfamily 7 of the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family, antiquitin performs NAD(P)+-dependent oxidation of aldehydes generated by alcohol metabolism, lipid peroxidation, and other cases of oxidative stress, to their corresponding carboxylic acids .[7][8][9] In addition, antiquitin plays a role in protecting cells and tissues from the damaging effects of osmotic stress, presumably through the generation of osmolytes.[8] Antiquitin may also play a protective role for DNA in cell growth, as the protein is found to be up-regulated during the G1–S phase transition, which undergoes the highest degree of oxidative stress in the cell cycle.[7][8] Furthermore, antiquitin functions as an aldehyde dehydrogenase for α-AASA in the pipecolic acid pathway of lysine catabolism.[7][10]

Localization

Antiquitin function and subcellular localization are closely linked, as it functions in detoxification in the cytosol, lysine catabolism in the mitochondrion, and cell cycle progression in the nucleus.[7][8] In particular, antiquitin localizes to the mitochondria in kidney and liver to contribute to the synthesis of betaine, a chaperone protein that protects against osmotic stress.[8]

Clinical significance

Mutations in this gene cause pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy, which involves a combination of various seizure types that do not respond to standard anticonvulsants, but are treatable via administration of pyridoxine hydrochloride.[10][11] These pyridoxine-dependent seizures have been linked to the failure to oxidize α-AASA in patients due to mutated antiquitin. Additionally, antiquitin is implicated in other diseases, including cancer, diabetes, osteoporosis, premature ovarian failure and Huntington's disease, though the exact mechanisms remain unclear.[7][12]

References

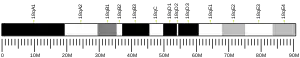

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000164904 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000053644 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Skvorak AB, Robertson NG, Yin Y, Weremowicz S, Her H, Bieber FR, Beisel KW, Lynch ED, Beier DR, Morton CC (December 1997). "An ancient conserved gene expressed in the human inner ear: identification, expression analysis, and chromosomal mapping of human and mouse antiquitin (ATQ1)". Genomics. 46 (2): 191–9. doi:10.1006/geno.1997.5026. PMID 9417906.

- "Entrez Gene: ALDH7A1".

- Chan, CL; Wong, JW; Wong, CP; Chan, MK; Fong, WP (30 May 2011). "Human antiquitin: structural and functional studies". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 191 (1–3): 165–70. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2010.12.019. PMID 21185811.

- Brocker C, Lassen N, Estey T, Pappa A, Cantore M, Orlova VV, Chavakis T, Kavanagh KL, Oppermann U, Vasiliou V (June 2010). "Aldehyde dehydrogenase 7A1 (ALDH7A1) is a novel enzyme involved in cellular defense against hyperosmotic stress". J. Biol. Chem. 285 (24): 18452–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.077925. PMC 2881771. PMID 20207735.

- Brocker C, Cantore M, Failli P, Vasiliou V (May 2011). "Aldehyde dehydrogenase 7A1 (ALDH7A1) attenuates reactive aldehyde and oxidative stress induced cytotoxicity". Chem. Biol. Interact. 191 (1–3): 269–77. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2011.02.016. hdl:2158/513857. PMC 3387551. PMID 21338592.

- Mills PB, Struys E, Jakobs C, Plecko B, Baxter P, Baumgartner M, Willemsen MA, Omran H, Tacke U, Uhlenberg B, Weschke B, Clayton PT (Mar 2006). "Mutations in antiquitin in individuals with pyridoxine-dependent seizures". Nature Medicine. 12 (3): 307–9. doi:10.1038/nm1366. PMID 16491085. S2CID 27940375.

- Scharer G, Brocker C, Vasiliou V, Creadon-Swindell G, Gallagher RC, Spector E, Van Hove JL (Oct 2010). "The genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy due to mutations in ALDH7A1". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 33 (5): 571–81. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9187-2. PMC 3112356. PMID 20814824.

- Giacalone NJ, Den RB, Eisenberg R, Chen H, Olson SJ, Massion PP, Carbone DP, Lu B (May 2013). "ALDH7A1 expression is associated with recurrence in patients with surgically resected non-small-cell lung carcinoma". Future Oncology. 9 (5): 737–45. doi:10.2217/fon.13.19. PMC 5341386. PMID 23647301.

- Wang H, Tong L, Wei J, Pan W, Li L, Ge Y, Zhou L, Yuan Q, Zhou C, Yang M (Dec 2014). "The ALDH7A1 genetic polymorphisms contribute to development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma". Tumour Biology. 35 (12): 12665–70. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2590-9. PMID 25213698. S2CID 12775026.

Further reading

- Stelzl U, Worm U, Lalowski M, Haenig C, Brembeck FH, Goehler H, Stroedicke M, Zenkner M, Schoenherr A, Koeppen S, Timm J, Mintzlaff S, Abraham C, Bock N, Kietzmann S, Goedde A, Toksöz E, Droege A, Krobitsch S, Korn B, Birchmeier W, Lehrach H, Wanker EE (Sep 2005). "A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome". Cell. 122 (6): 957–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0010-8592-0. PMID 16169070. S2CID 8235923.

- Been JV, Bok LA, Andriessen P, Renier WO (Dec 2005). "Epidemiology of pyridoxine dependent seizures in the Netherlands". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 90 (12): 1293–6. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.075069. PMC 1720231. PMID 16159904.

- Guo Y, Tan LJ, Lei SF, Yang TL, Chen XD, Zhang F, Chen Y, Pan F, Yan H, Liu X, Tian Q, Zhang ZX, Zhou Q, Qiu C, Dong SS, Xu XH, Guo YF, Zhu XZ, Liu SL, Wang XL, Li X, Luo Y, Zhang LS, Li M, Wang JT, Wen T, Drees B, Hamilton J, Papasian CJ, Recker RR, Song XP, Cheng J, Deng HW (Jan 2010). Georges M (ed.). "Genome-wide association study identifies ALDH7A1 as a novel susceptibility gene for osteoporosis". PLOS Genetics. 6 (1): e1000806. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000806. PMC 2794362. PMID 20072603.

- Gallagher RC, Van Hove JL, Scharer G, Hyland K, Plecko B, Waters PJ, Mercimek-Mahmutoglu S, Stockler-Ipsiroglu S, Salomons GS, Rosenberg EH, Struys EA, Jakobs C (May 2009). "Folinic acid-responsive seizures are identical to pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy". Annals of Neurology. 65 (5): 550–6. doi:10.1002/ana.21568. PMID 19142996. S2CID 42052285.

- Salomons GS, Bok LA, Struys EA, Pope LL, Darmin PS, Mills PB, Clayton PT, Willemsen MA, Jakobs C (Oct 2007). "An intriguing "silent" mutation and a founder effect in antiquitin (ALDH7A1)". Annals of Neurology. 62 (4): 414–8. doi:10.1002/ana.21206. PMID 17721876. S2CID 38972972.

- Wong JW, Chan CL, Tang WK, Cheng CH, Fong WP (Jan 2010). "Is antiquitin a mitochondrial Enzyme?". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 109 (1): 74–81. doi:10.1002/jcb.22381. PMID 19885858. S2CID 30021201.

- Kanno J, Kure S, Narisawa A, Kamada F, Takayanagi M, Yamamoto K, Hoshino H, Goto T, Takahashi T, Haginoya K, Tsuchiya S, Baumeister FA, Hasegawa Y, Aoki Y, Yamaguchi S, Matsubara Y (Aug 2007). "Allelic and non-allelic heterogeneities in pyridoxine dependent seizures revealed by ALDH7A1 mutational analysis". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 91 (4): 384–9. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.02.010. PMID 17433748.

- Striano P, Battaglia S, Giordano L, Capovilla G, Beccaria F, Struys EA, Salomons GS, Jakobs C (Apr 2009). "Two novel ALDH7A1 (antiquitin) splicing mutations associated with pyridoxine-dependent seizures". Epilepsia. 50 (4): 933–6. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01741.x. PMID 18717709. S2CID 41230917.

- Kluger G, Blank R, Paul K, Paschke E, Jansen E, Jakobs C, Wörle H, Plecko B (Oct 2008). "Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy: normal outcome in a patient with late diagnosis after prolonged status epilepticus causing cortical blindness". Neuropediatrics. 39 (5): 276–9. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1202833. PMID 19294602.

- Plecko B, Paul K, Paschke E, Stoeckler-Ipsiroglu S, Struys E, Jakobs C, Hartmann H, Luecke T, di Capua M, Korenke C, Hikel C, Reutershahn E, Freilinger M, Baumeister F, Bosch F, Erwa W (Jan 2007). "Biochemical and molecular characterization of 18 patients with pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy and mutations of the antiquitin (ALDH7A1) gene". Human Mutation. 28 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1002/humu.20433. PMID 17068770. S2CID 23732422.

- Kaczorowska M, Kmiec T, Jakobs C, Kacinski M, Kroczka S, Salomons GS, Struys EA, Jozwiak S (Dec 2008). "Pyridoxine-dependent seizures caused by alpha amino adipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency: the first polish case with confirmed biochemical and molecular pathology". Journal of Child Neurology. 23 (12): 1455–9. doi:10.1177/0883073808318543. PMID 18854520. S2CID 31665261.

- Bennett CL, Chen Y, Hahn S, Glass IA, Gospe SM (May 2009). "Prevalence of ALDH7A1 mutations in 18 North American pyridoxine-dependent seizure (PDS) patients". Epilepsia. 50 (5): 1167–75. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01816.x. PMID 19128417. S2CID 35563845.

- Bok LA, Struys E, Willemsen MA, Been JV, Jakobs C (Aug 2007). "Pyridoxine-dependent seizures in Dutch patients: diagnosis by elevated urinary alpha-aminoadipic semialdehyde levels". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 92 (8): 687–9. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.103192. PMC 2083882. PMID 17088338.

- Tomarev SI, Wistow G, Raymond V, Dubois S, Malyukova I (Jun 2003). "Gene expression profile of the human trabecular meshwork: NEIBank sequence tag analysis". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 44 (6): 2588–96. doi:10.1167/iovs.02-1099. PMID 12766061.

External links

- GeneReview/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Pyridoxine-Dependent Seizures

- Human ALDH7A1 genome location and ALDH7A1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.