2022 Uruguayan Law of Urgent Consideration referendum

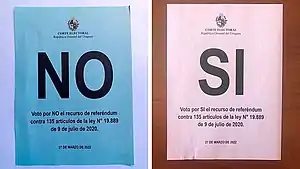

A referendum on the Urgent Consideration Law was held in Uruguay to ask the electorate if 135 articles of Law 19,889 (known as the "Urgent Consideration Law", "Urgency Law" or simply "LUC") – approved by the General Assembly in 2020 and considered as the main legislative initiative of the coalition government of President Luis Lacalle Pou — should be repealed.[1][2] It was the result of a campaign promoted by various social and political actors such as the national trade union center PIT-CNT and the opposition party Broad Front. On 8 July 2021, almost 800,000 adhesions were delivered to the Electoral Court, exceeding 25% of the total number of registered voters who are constitutionally required to file a referendum appeal against a law.[3][4]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Referendum appeal against 135 articles of Law No. 19,889 of 9 July 2020 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome | Repeal rejected | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results by department: Yes No | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Article 168 of the Uruguayan Constitution establishes that the Executive Branch may submit bills to the General Assembly declaring them "of urgent consideration". In this case, the House that receives the bill in the first instance has a period of 45 days to put it into consideration; if the term expires without the bill being rejected, it is considered approved in its original form and is communicated to the other House, which has a term of 30 days, and in case of approving a bill with modifications, it must re-enter the first House where it will have another 15 days for consideration. If after this period there is no express statement that demonstrates common agreement between the houses regarding the modifications, the project is sent to the General Assembly, which will have 10 days to consider it.[5] With this constitutional mechanism, if a bill does not receive parliamentary approval within the stipulated periods, it automatically becomes law in the form in which it was sent by the Executive Power.[6]

Since the transition to democracy in 1985, only 13 bills were sent to Parliament with a declaration of "urgent consideration" (0.003% of the total bills sent by the Executive in that period), of which 9 were approved and 4 were rejected.[7] All governments applied the mechanism, except for the second terms of Julio María Sanguinetti and Tabaré Vázquez. However, in most of these cases urgent consideration was used for specific topics and only 3 projects fall into the category of “Omnibus bill”, based on the number of topics covered.[7]

For the repeal to happen, the total of yes votes had to reach the absolute majority of valid votes, which included blank ones.[8] It thus failed, only 48,67 % of the total votes including blank ones being for the repeal.

Background

In 2018, the then presidential pre-candidate Luis Lacalle Pou of the National Party (PN) declared that his first measure in case of assuming the presidency in 2020 would be to send a bill to the Legislative Branch with the label of "urgent consideration", which would be the result of the negotiation between the members of a possible coalition government and whose content would include "everything that needs to be modified in the State", covering "education, security, housing, economy, administrative issues".[9][10] The aim of the initiative would be "to take advantage of the first year of government to quickly apply the changes considered necessary".[11] Pablo Da Silveira, then Lacalle campaign programmatic coordinator and Minister of Education and Culture in the subsequent government, referred to the fact that with this "omnibus law" actions could be taken in a shortened period with respect to a budget law, which requires a process more extensive legislature.[12]

In March 2019, Lacalle Pou officially launched his campaign for the presidential primaries, which were held on 30 June of the same year.[13] He obtained 53.77 percent of the vote, defeating Juan Sartori, Jorge Larrañaga, Enrique Antía and Carlos Iafigliola.[14] Shortly after the victory, the nationalist candidate's campaign team began to draft the Law of Urgent Consideration (LUC), with Rodrigo Ferrés as the person in charge.[15] It was stated then that the bill would have between 300 and 500 articles and that its content would be based on the government program of the PN.[16] It was criticized from the Broad Front (FA), the Socialist Party (PS) affirmed that the mechanism would be unconstitutional since its use requires an identified pre-existing urgency and not one created "for political or ideological reasons or government priorities".[17]

Originally, the Lacalle Pou campaign team planned to finish the drafting of the LUC bill in October 2019, so that it would be presented prior to the first round of the general election, to be held on the 27th of that month.[18] However, this did not happen. In the election, the FA and the PN were the two most voted parties, with 39 and 28.6 percent of the vote, respectively. This result led to a second round between the candidates of each one to be held in November 2019, towards which all the main opposition parties lined up behind Lacalle Pou, forming the Coalición Multicolor.[19][20] This alliance presented a common programmatic agreement known as "Commitment for the Country".[21] In the second round, Lacalle Pou was elected the 42nd president of Uruguay with 50.79 percent of the vote. The first draft of the LUC bill was released in January 2020, containing 457 articles divided into 10 chapters.[22] It underwent subsequent modifications as a result of the negotiation between the different members of the Coalición Multicolor and the final version was presented on 9 April, with 502 articles.[23][24]

The final project of the LUC entered Parliament on 23 April 2020.[25] Both in the Senate and in the Chamber of Representatives, special commissions made up of legislators from all political parties with parliamentary representation were formed for its analysis.[26][27] Various individuals, public bodies, institutions and organizations were summoned by these commissions to learn their views on its content.[28][29]

After 25 articles were eliminated and more than 300 modified, the law was approved by the Senate in the first instance on 6 June 2020,[30] after which it entered the Chamber of Representatives where 32 changes were introduced and it was approved on 5 July.[31][32] Finally, the upper house approved its final version on the 8th of the same month with only the votes of the ruling coalition, and the Executive Power promulgated it a day later.[33][34] President Lacalle Pou described it as a "necessary, fair and popular" instrument.[35]

Initiative

Before the LUC bill was sent to the Legislative Branch and later during the parliamentary discussion, the PIT-CNT trade union center spoke out against its contents and the use of the constitutional remedy of "urgent consideration", considering it a mechanism undemocratic, considering that it "limited" the political and social debate.[36][37] On 4 June 2020, the workers' union held a demonstration in front of the Legislative Palace, during which its secretary general, Marcelo Abdala, stated that the LUC was not meeting the needs of the population in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic " neither in form nor in content.[38] The ANCAP Federation (Fancap), a union of workers of the state fuel company ANCAP, was one of the first organizations to express itself in favor of filing a referendum against the LUC, considering it contrary to "the interests of the working class", according to its president Gerardo Rodríguez.[39] One of the main points of objection was the elimination of ANCAP's monopoly for the import, export and refining of crude oil and derivatives, an issue that generated discussion even within the ruling coalition itself,[40] and ended up being excluded from the bill during the parliamentary debate.[41] Instead, it was established that the price of fuels be defined by the Executive Power, with an adjustment in line with the import parity price with a periodicity not exceeding sixty days,[42] against which Fancap also manifested itself in disagreement.[43]

In May, the National Political Board of the Broad Front expressed its rejection of the "urgent consideration" mechanism and characterized the project as "inopportune, unconstitutional and undemocratic".[44] During the parliamentary analysis, its legislators worked to incorporate various modifications, but they considered that the final version did not present substantial changes with respect to the original and, therefore, they maintained their negative vote on the bill,[45] despite voting in favor of almost 50% of the articles.[46]

On 9 September, the PIT-CNT officially announced for the first time that it would begin to analyze the possibility of developing a campaign with this objective, although at the moment it was not something definite.[47] The campaign to collect signatures to file a referendum was confirmed on 17 October by Intersocial,[48] a space made up of various social organizations in addition to the PIT-CNT, such as the Uruguayan Federation of Cooperatives for Mutual Savings (FUCVAM), the Intersocial Feminista and the Federation of University Students of Uruguay (FEUU).[49][50] Two days later, on the 19th, the Broad Front decided to join the campaign,[51] a decision ratified on the 23rd by the Board.[52]

In Uruguay there are two ways to file a referendum appeal against a law before the Electoral Court.[53] In one of them, it requires reaching the adhesions of 25% of the total number of registered voters in a period corresponding to the first year after the promulgation of the law and directly leads to the holding of the referendum.[54] On the other hand, the other route requires reach at least 2% of the total number of registered voters eligible to vote within a period of 150 days after the enactment of the law and gives rise to the holding of an election with a non-compulsory vote known as a pre-referendum, in which if 25% vote affirmatively, a referendum must be held.[55] Depending on the time required to collect signatures in each case, the first form is popularly known as "the long one" and the second as "the short one".[56] At first, both the PIT-CNT and the Intersocial proposed to follow the "long way".[57][58] On the Broad Front, this issue generated divisions, since the Communist Party (PC) and the Socialist Party supported the "long way", but other sectors such as the Movement of Popular Participation (MPP), the Uruguay Assembly (AU) and the Renovating Force (FR) preferred the "short way" given the risk implied by the high percentage of signatures required by the other mechanism.[59]

On 8 December 2020, it was formally reported that the FA had also opted for the "long way", in agreement with social organizations.[60][61] Another of the most important issues was whether the referendum would seek a total or partial repeal of the LUC and, in the latter case, which articles. In early December, as a result of an agreement between the different actors, it was announced that they would seek to repeal 133 articles, referring to the issues of public security, the economy, public companies, the agricultural sector, labor relations, social security and housing.[62] In addition to the fact that among the articles to be repealed there were some that were voted by the FA in Parliament.[63]

On 14 December, made up of the PIT-CNT, the FA and the Intersocial, the National Pro-Referendum Commission (later the National Commission for the YES) was installed.[62] Four days later, the process formally began before the Electoral Court,[64] and on 29 December 2020, the campaign to collect signatures began to repeal 135 articles of the Law of Urgent Consideration.[65]

Opinion polls

| Date(s) conducted | Will you vote to repeal the 135 articles of the LUC? | Undecided | Blank/spoilt | Lead | Sample | Conducted by | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||

| 2022 | |||||||

| 18–22 March | 43% | 43% | 10% | 4% | N/A | 400 | UPC |

| 17–22 March | 41% | 44% | 14% | 1% | 3% | 804 | Opción |

| 11–20 March | 41% | 45% | 10% | 4% | 4% | 1,006 | Cifra |

| 11–14 March | 36% | 41% | 19% | 4% | 5% | 900 | Factum |

| 19 February – 2 March | 34% | 35% | 28% | 3% | 1% | 1,209 | Equipos |

| 17–26 February | 36% | 38% | 22% | 4% | 2% | 800 | Opción |

| 12–22 February | 32% | 41% | 22% | 5% | 9% | 900 | Factum |

| 10–27 February | 33% | 45% | 20% | 2% | 12% | 809 | Cifra |

| 4–11 February | 47% | 42,6% | 10,4% | N/A | 4,4% | N/A | Nómade |

| 26 January – 1 February | 31% | 41% | 26% | 2% | 10% | 500 | Equipos |

| 14–24 January | 43% | 38% | 15% | 3% | 5% | 400 | UPC |

| 2021 | |||||||

| 9–27 December | 49,4% | 41,2% | 9,4% | N/A | 8,2% | N/A | Nómade |

| 25 November – 2 December | 33% | 46% | 18% | 3% | 13% | 500 | Equipos |

| 6–15 November | 39% | 51% | 10% | 12% | 900 | Factum | |

| 29 October – 8 November | 37% | 39% | 19% | 5% | 2% | 800 | Opción |

| 28 October – 7 November | 41% | 48% | 11% | N/A | 7% | 800 | Cifra |

| 1–14 September | 45% | 50% | 5% | 5% | 900 | Factum | |

| 26 August – 3 September | 34% | 44% | 22% | N/A | 10% | 707 | Cifra |

| 9–16 August | 41% | 37% | 19% | 3% | 4% | 800 | Opción |

| 22–31 July | 43% | 40% | 11% | 2% | 3% | 1,500 | Radar |

| 24 June – 3 July | 34% | 43% | 23% | N/A | 10% | 1,003 | Cifra |

| 13–20 May | 40% | 38% | 22% | N/A | 2% | 824 | Opción |

Results

Only three departments voted in favor of the repeal : Canelones, Montevideo, and Paysandú. While those against the repeal represented only 50.02%, the repeal failed by a wider margin as 50% of the total votes including blank votes was needed, when only 48.67% of this total voted for the repeal. The initial count had the yes at 48.82%, the No at 49.86% and the blank votes at 1.32%. While the failure of the votes for repeal to reach 50% was enough to declare a result, the margin was thin enough for the total of unassessed votes (those from people voting in a different polling station than their registered ones, usually ignored if the margin is higher) to be higher, forcing them to be counted for the first time.

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| For | 1,078,425 | 48.67 |

| 1,108,360 | 50.02 | |

| Blank | 29,121 | 1.31 |

| Invalid votes[66] | 83,031 | 3.61 |

| Total | 2,298,937 | 100 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 2,684,131 | 85.65 |

| Source: Corte Electoral | ||

By department

| Department | For | % | Against | % | Blank | % | Unassessed | Invalid | Total | Electorate | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artigas | 16,556 | 32.25 | 34,232 | 66.68 | 548 | 1.07 | 11 | 1,160 | 52,507 | 63,121 | 83.18 |

| Canelones | 180,280 | 53.24 | 153,621 | 45.36 | 4,744 | 1.40 | 77 | 14,549 | 353,271 | 409,779 | 86.21 |

| Cerro Largo | 23,423 | 38.11 | 37,255 | 60.61 | 791 | 1.29 | 20 | 1,765 | 63,254 | 73,210 | 86.40 |

| Colonia | 38,872 | 43.62 | 49,162 | 55.16 | 1,087 | 1.22 | 37 | 3,173 | 92,331 | 106,001 | 87.10 |

| Durazno | 17,522 | 41.06 | 24,599 | 57.65 | 552 | 1.29 | 17 | 1,452 | 44,142 | 50,636 | 87.18 |

| Flores | 6,732 | 35.08 | 12,183 | 63.48 | 278 | 1.45 | 6 | 641 | 19,840 | 22,600 | 87.79 |

| Florida | 21,359 | 43.49 | 27,168 | 55.32 | 582 | 1.19 | 8 | 2,135 | 51,252 | 57,597 | 88.98 |

| Lavalleja | 15,237 | 35.20 | 27,359 | 63.20 | 694 | 1.60 | 3 | 1,726 | 45,019 | 51,040 | 88.20 |

| Maldonado | 47,945 | 40.39 | 69,161 | 58.26 | 1,600 | 1.35 | 27 | 5,188 | 123,921 | 142,277 | 87.10 |

| Montevideo | 468,268 | 55.86 | 358,775 | 42.80 | 11,216 | 1.34 | 210 | 32,370 | 870,839 | 1,029,113 | 84.62 |

| Paysandú | 40,391 | 50.97 | 37,975 | 47.92 | 879 | 1.11 | 18 | 2,502 | 81,765 | 95,285 | 85.81 |

| Río Negro | 17,237 | 45.39 | 20,257 | 53.34 | 480 | 1.26 | 9 | 1,178 | 39,161 | 46,490 | 84.24 |

| Rivera | 18,521 | 25.38 | 53,712 | 73.60 | 747 | 1.02 | 39 | 1,630 | 74,649 | 89,555 | 83.36 |

| Rocha | 22,498 | 43.57 | 28,301 | 54.81 | 839 | 1.62 | 4 | 2,279 | 53,921 | 62,454 | 86.34 |

| Salto | 41,633 | 47.66 | 44,790 | 51.28 | 926 | 1.06 | 22 | 2,026 | 89,397 | 104,046 | 85.92 |

| San José | 33,466 | 46.46 | 37,658 | 52.28 | 912 | 1.27 | 25 | 2,817 | 74,878 | 84,021 | 89.12 |

| Soriano | 28,931 | 46.93 | 31,958 | 51.84 | 753 | 1.22 | 15 | 2,230 | 63,887 | 75,294 | 84.85 |

| Tacuarembó | 25,514 | 38.69 | 39,464 | 59.85 | 965 | 1.46 | 12 | 2,196 | 68,151 | 78,732 | 86.56 |

| Treinta y Tres | 14,040 | 39.78 | 20,730 | 58.73 | 528 | 1.50 | 10 | 1,444 | 36,752 | 42,880 | 85.71 |

| Total | 1,078,425 | 48.67 | 1,108,360 | 50.02 | 29,121 | 1.31 | 570 | 82,461 | 2,298,937 | 2,684,131 | 85.65 |

| Source: Corte Electoral | |||||||||||

References

- "LUC referendum in Uruguay scheduled for March 27". MercoPress. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- de 2020, 8 de Julio. "El Congreso uruguayo aprobó la Ley de Urgente Consideración, clave para el gobierno de Lacalle Pou". infobae (in European Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ElPais. "Comisión Pro Referéndum entregó 797.261 firmas a la Corte Electoral". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Constitución de la República Oriental del Uruguay". www.impo.com.uy. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Constitución de la República Oriental del Uruguay". www.impo.com.uy. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- diaria, la (21 January 2020). "¿Qué es una ley de urgencia, cuáles son los plazos de su tratamiento parlamentario y quién ha utilizado la herramienta?". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Chasquetti, Daniel (30 September 2019). "Los proyectos de ley de urgente consideración en Uruguay". Programa de Estudios Parlamentarios (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- What is the Law of Urgent Consideration of Lacalle Pou that Uruguayans ratified in the referendum

- "Luis Lacalle Pou: "El poder no lo voy a compartir con los sindicatos" – Información – 21/10/2018 – EL PAÍS Uruguay". 11 November 2020. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Noticias | Lacalle Pou: "Están soltando cucos por miedo a soltar la teta"". noticias.perfil.com. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Observador, El. "Lacalle Pou piensa en un "shock de austeridad" porque ajuste gradual "no sirve"". El Observador. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Observador, El. "Pablo da Silveira: "Nos gustaría que ministro y subsecretario no sean del mismo partido"". El Observador. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Lacalle lanza su campaña y dice que es su "mejor momento" para gobernar Uruguay". www.efe.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ElPais (July 2019). "Lacalle Pou, Martínez y Talvi ganan las elecciones internas". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Comando de Lacalle Pou ya redacta ley de urgente consideración de 500 artículos". 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Doce puntos clave del proyecto de urgente consideración que prepara Lacalle Pou". 29 September 2020. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Socialistas: ley de urgente consideración propuesta por Lacalle es "inconstitucional"". 18 July 2021. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Observador, El. "Doce puntos clave del proyecto de urgente consideración que prepara Lacalle Pou". El Observador. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Uruguay presidential election to go to second round". BBC News. 28 October 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "La oposición se alineó detrás de Lacalle Pou y Martínez enfrenta la caída del FA". subrayado.com.uy (in Spanish). 28 October 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Qué dice el documento firmado por la coalición y cuáles fueron los cambios para el acuerdo final". 18 July 2021. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ElPais. "Este es el borrador del proyecto de ley de urgente consideración impulsado por Lacalle". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Discurso, designaciones y ley de urgencia: así será la última semana de Lacalle Pou antes de asumir". 18 July 2021. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Conocé el proyecto de ley urgente que el gobierno envió a todos los partidos". 18 July 2021. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Ingresó al Parlamento la ley de urgencia; "¡Cumplimos!", sostuvo Lacalle Pou – Información – 23/04/2020 – EL PAÍS Uruguay". 7 May 2021. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "COMISION ESPECIAL PARA EL ESTUDIO DEL PROYECTO DE LEY CON DECLARATORIA DE URGENTE CONSIDERACIÓN | Parlamento del Uruguay". 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "ESPECIAL PARA EL TRATAMIENTO DEL PROYECTO DE LEY CON DECLARATORIA DE URGENTE CONSIDERACIÓN | Parlamento del Uruguay". 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Citaciones | Parlamento del Uruguay". 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Citaciones | Parlamento del Uruguay". 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "SENADO APROBÓ LEY DE URGENTE CONSIDERACIÓN | Parlamento del Uruguay". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Así quedó el proyecto final de la LUC, que sufrió varios cambios". 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "La Cámara de Diputados aprobó la Ley de Urgente Consideración: ahora volverá al senado". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Senado aprobó la LUC con 18 en 30 votos con críticas del Frente Amplio – Información – 08/07/2020 – EL PAÍS Uruguay". 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "El Poder Ejecutivo promulgó la Ley de Urgente Consideración". 12 February 2022. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "La ley de urgente consideración es "popular, justa y necesaria", dijo Luis Lacalle Pou – Información – 13/07/2020 – EL PAÍS Uruguay". 6 February 2021. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Unánime rechazo a Ley de Urgente Consideración – PIT-CNT". www.pitcnt.uy (in European Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Pit-Cnt analiza realizar manifestación contra la LUC y detalló críticas hacia el proyecto – Información – 18/05/2020 – EL PAÍS Uruguay". 13 June 2021. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Pit-Cnt se movilizó en rechazo a la LUC: Abdala dijo que "la verdadera emergencia es la gente" – Información – 04/06/2020 – EL PAÍS Uruguay". 13 January 2022. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Portal Medios Públicos". Portal Medios Públicos (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Desmonopolización de Ancap en la LUC vuelve a generar diferencias en la coalición". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "La coalición sacará de la LUC la desmonopolización de ANCAP tras falta de acuerdo interno". subrayado.com.uy (in Spanish). 22 May 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Ley N° 19889". www.impo.com.uy. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- diaria, la (23 September 2020). "FANCAP: el Presupuesto entrega "instalaciones e infraestructura logística de ANCAP al capital privado"". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Resolución sobre Ley de Urgente Consideración". frenteamplio.uy (in European Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- diaria, la (8 July 2020). "Senado dio sanción definitiva a la ley de urgente consideración". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Oposición uruguaya quiere derogar ley relámpago de Lacalle". AP NEWS. 8 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- diaria, la (10 September 2020). "PIT-CNT resolvió "abrir un proceso de referéndum" contra la ley de urgente consideración". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- diaria, la (17 October 2020). "La Intersocial promoverá un referéndum contra la ley de urgente consideración". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Crean la Intersocial, nuevo bloque que busca llevarle reclamos al gobierno – Información – 03/06/2020 – EL PAÍS Uruguay". 1 March 2021. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Nueva plataforma Intersocial pone énfasis en crear "una renta transitoria de emergencia"". Montevideo Portal (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- diaria, la (17 October 2020). "Plenario del Frente Amplio decidió apoyar el referéndum contra la LUC". la diaria (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Frente Amplio resolvió acompañar referéndum contra LUC pero no definió el mecanismo". 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "Los caminos del Frente Amplio para realizar un referéndum contra la ley de urgencia". 970 Universal (in Spanish). 29 April 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Ley N° 17244". 9 April 2021. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Ley N° 16017". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Pre referéndum sobre Ley Trans: Cómo se vota y por qué – Radiomundo En Perspectiva". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Crece ambiente para promover referéndum contra LUC | Caras y Caretas". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Referéndum contra LUC: Intersocial opta por juntar 700.000 firmas a julio de 2021". 17 July 2021. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ElPais (23 October 2020). "El Frente Amplio se inclina por el "camino largo" para derogar la LUC". Diario EL PAIS Uruguay (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "FA resolvió avanzar por el "camino largo" para recolectar firmas contra la LUC | la diaria | Uruguay". 17 July 2021. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "El momento ya llegó – PIT-CNT". 5 February 2021. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Comisión Pro Referéndum detalló los 133 artículos que pretenderá derogar de la LUC: mirá". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Frente Amplio resolvió intentar derogar artículos de la LUC que votó en el Parlamento". 17 July 2021. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Comenzó el camino legal en la Corte Electoral por referéndum de la LUC – PIT-CNT". 1 March 2021. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- "Se lanzó la campaña pro referéndum para derogar 135 artículos de la ley de urgencia". 14 July 2021. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- Including 570 invalid votes out of the previously unassessed votes