1940 Bolivian general election

General elections were held in Bolivia on 10 March 1940, electing both a new President of the Republic and a new National Congress. The elections were the first in six years since 1934 and the first not to be annulled in nine years since the general election of 1931.[1]

| ||||||||||||||||||||

President, all 109 Deputies and 27 Senators in the National Congress | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 104,612 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 64.54% | |||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

Background

Since 1936, Bolivia had experienced a left-wing shift in government under the Military Socialist regimes of David Toro and Germán Busch. This period came to an end when Busch committed suicide on 23 August 1939, four months after dissolving the assembly and declaring himself dictator. Immediately following the death of Busch, the armed forces appointed General Carlos Quintanilla, the commander-in-chief of the army, to the office of president. Quintanilla soon set about reversing course on the more radical elements of the previous governments and returning the country to the conservative status quo prior to the Chaco War.

Though Quintanilla attempted to exercise a longer government, the prolonged indecision to call elections was met by opposition from the traditional political parties which sought to reassert themselves for the first time since the coup d'état which deposed them in 1936. Among the voices demanding elections was General Enrique Peñaranda who declared to the press that the country urgently needed "direct general elections to be called."[2] Finally, a group of representatives from the Liberal (PL), Genuine Republican (PRG), and Socialist Republican (PRG), parties addressed President Quintanilla with the warning that "Deferring for a longer time, without valid reasons, [...] the call for direct elections, will lead public opinion to the conviction that their participation in the electoral plebiscite will only serve to consolidate and legalize public powers [...] and that, therefore, will not be the authentic expression of the popular will."[2]

Given the pressure, Quintanilla put out the call on 6 October 1939, over a month after taking power, for new elections for president and vice president to be held on 10 March 1940.[3] However, only elections for president would occur as on 4 December 1939 the office of vice president was abolished in order to silence calls for Enrique Baldivieso, the former vice president to Germán Busch, to succeed to the presidency.[4]

Campaign

To secure their chances at victory, the PL, PRG, and PRS consolidated into the Concordance electoral alliance.[5] General Enrique Peñaranda, one of the nearest approximations to a war hero produced by the Chaco War, was brought forth as the coalition's presidential candidate.[5] Peñaranda had been a member of the senior officer corps which after the Chaco War was forced to step aside in favor of the younger generation of officers represented by Germán Busch.

These young officers presented as their presidential candidate General Bernardino Bilbao Rioja, the new commander-in-chief of the army who represented the Military Socialist ideology of Toro and the deceased Busch.[6] Attempts by the mining oligarchy and the traditional parties to discredit Bilbao as a despot attempting to promulgate a leftist dictatorship were unsuccessful.[2] Faced with the possibility that Bilbao could conceivably win, the Quintanilla government summoned him to the government palace where he was beaten, gagged, and deported to Arica, Chile.[6] Though Bilbao's return was negotiated under threat of a military revolt from the young officers, he was sent directly from exile to London as a military attaché, removing him from circulation as a viable candidate.

As a result, Peñaranda's main electoral opposition came from José Antonio Arze. One of the primary sociologists and Marxist theorists in Bolivia, Arze had just that year returned from exile in Chile, having proven too far left even for the Military Socialist regime of David Toro which deported him in September 1936.[7] In April 1939, while still in Chile, Arze had formed the Bolivian Left Front (FIB), publishing a manifesto naming the FIB a union of the entire left-wing political spectrum. Despite this, the FIB maintained distinctly Marxist characteristics. For the 1940 elections, Arze ran as an independent as part of the FIB alliance.[8]

Results

President

Given the suppression of the electoral opposition, Peñaranda and the Concordance coalition won the 10 March elections easily with a popular vote margin of 85.99% to Arze's 11.32% and just 2.69% in favor of Bilbao. Despite the clear victory, the second place success of Arze at almost 15% indicated continued support for the left-wing in Bolivia and paved the way for the FIB to form the Revolutionary Left Party (PIR), one of the most influential leftist parties in 1940s Bolivia, five months later.[9][7]

Peñaranda was inaugurated as constitutional president on 15 April 1940.[10]

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrique Peñaranda | Concordance | 58,060 | 85.99 | |

| José Antonio Arze | Bolivian Left Front | 7,645 | 11.32 | |

| Bernardino Bilbao Rioja | Independent | 1,813 | 2.69 | |

| Total | 67,518 | 100.00 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 104,612 | – | ||

| Source: Gamboa[11] | ||||

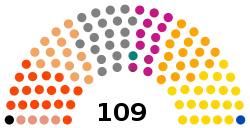

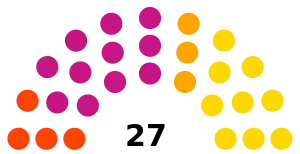

Congress

Despite Peñaranda's wide margin of victory, the legislative results were much closer. Right-wing parties (the traditional Liberals (PL), Genuine Republicans (PRG), and Socialist Republicans (PRS), as well as the Radical Party (PR) and affiliated independents, including those associated with the Bolivian Socialist Falange (FSB)) won 61 seats in the Chamber and 23 in the Senate. Left-wing parties (the United Socialist Party (PSU), the Independent Socialist Party (PSI, a precursor to the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR)), the Popular Front of Potosí (FPP), the Workers Socialist Party (PSOB), and affiliated independents) won 48 seats in the Chamber and four in the Senate.

As such, while conservatives held a large majority in the Chamber of Senators, their lead of just 13 seats in the Chamber of Deputies was much narrower. The relative success of the left-wing parties in the legislative elections compared to the presidential elections showed that many Bolivian citizens, while perhaps not as far left as the Communist International affiliated coalition of José Antonio Arze, still supported left-wing policies.

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | |||||

| Deputies | Senators | |||||||

| Liberal Party | 21 | 9 | ||||||

| United Socialist Party | 18 | 4 | ||||||

| Genuine Republican Party | 17 | 3 | ||||||

| Independent Socialist Party | 15 | 0 | ||||||

| Socialist Republican Party | 12 | 11 | ||||||

| Left-wing independents | 10 | 0 | ||||||

| Right-wing independents | 9 | 0 | ||||||

| Popular Front of Potosí | 4 | 0 | ||||||

| Radical Party | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| FSB independents | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Workers Socialist Party of Bolivia | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Total | 109 | 27 | ||||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 104,612 | – | ||||||

| Source: Bustillos & Peñaranda[12] | ||||||||

Notes

- Coalition consisting of PL, PRG, and PRS

- Frente de la Izquierda Boliviana (Bolivian Left Front, FIB), a precursor to the Revolutionary Left Party (PIR) formed in July of that year

References

- Political handbook of the world 1936. New York, 1936. P. 18.

- "1939 – CARLOS QUINTANILLA QUIROGA" (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- "Bolivia: Decreto Ley de 17 de noviembre de 1939". www.lexivox.org. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- "Bolivia: Decreto Ley de 4 de diciembre de 1939". www.lexivox.org. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- Fredrick B. Pike. The United States and the Andean republics: Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. Harvard University Press, 1977. p. 255.

- admins5 (19 November 2014). "Carlos Quintanilla (1888-1964)". www.educa.com.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- Shelchkov, Andrey A. (2017). UNA LEALTAD RECHAZADA: JOSÉ ANTONIO ARZE Y MOSCÚ. BOLIVIA, PRIMERA MITAD DEL SIGLO XX (PDF). Departamento de Historia, Universidad de Santiago de Chile.

- Gisbert 2003, p. 188

- admins5 (19 November 2014). "José Antonio Arze (1904-1955)". www.educa.com.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- "Bolivia: Ley de 14 de abril de 1940". www.lexivox.org. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- Walter Ríos Gamboa. Bolivia, hacia la democracía: apuntes histórico-políticos. Khana Cruz, 1979. P.161.

- Bustillos Vera, Jonny and Peñaranda Barrios, Carlos. Hechos y registros de la Revolución Nacional (1939-1946). La Paz, Bolivia: La Palabra, 1996. Pp.54-55.

Bibliography

- Gisbert, Carlos D. Mesa (2003). Presidentes de Bolivia: entre urnas y fusiles : el poder ejecutivo, los ministros de estado (in Spanish). Editorial Gisbert.