1935 Jérémie hurricane

The 1935 Jérémie hurricane, commonly referred to as the 1935 Haiti hurricane, was a highly destructive and catastrophic tropical cyclone that impacted the Greater Antilles and Honduras in October 1935, killing well over 2,000 people. Developing on October 18 over the southwestern Caribbean Sea, the storm proceeded to strike eastern Jamaica and southeastern Cuba while overwhelming southwestern Haiti in a deluge of rain. The hurricane—a Category 1 at its peak—completed an unusual reversal of its path on October 23, heading southwestward toward Central America. Weakened by its interaction with Cuba, the storm soon regained strength and made its final landfall near Cabo Gracias a Dios in Honduras on October 25. The cyclone weakened upon moving inland and dissipated two days later.

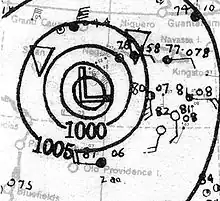

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on October 24, while restrengthening before its final landfall | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 18, 1935 |

| Dissipated | October 27, 1935 |

| Category 1 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 85 mph (140 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 988 mbar (hPa); 29.18 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | ~2,150 |

| Damage | $16 million (1935 USD) |

| Areas affected | Eastern Jamaica, eastern Cuba, southwestern Haiti, Honduras, northeastern Nicaragua |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1935 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Flooding and landslides in Jamaica took their toll on property, agricultural interests, and infrastructure; fruit growers on the island sustained about $2.5 million (1935 USD) in losses. Just off the coast, an unidentified vessel went down with her entire crew in the hostile conditions. Strong winds buffeted coastal sections of Cuba, notably in and around Santiago de Cuba. There, the hurricane demolished 100 homes and filled streets with debris. Only four people died in the country, thanks to the extensive pre-storm preparations. The storm did the most damage along the Tiburon Peninsula of southwestern Haiti, where catastrophic river flooding took the lives of up to 2,000 individuals, razed hundreds of native houses, and destroyed crops and livestock. The heaviest destruction took place around the towns of Jacmel and Jérémie; one early report estimated that 1,500 had been killed at the latter. Entire swaths of countryside were isolated for days, delaying both reconnaissance and relief efforts.

The hurricane later created devastating floods in Central America, chiefly in Honduras. Reported at the time to be the worst flood in the nation's history, the disaster decimated banana plantations and population centers after rivers flowed up to 50 ft (15 m) above normal. Torrents of floodwaters trapped hundreds of citizens in trees, on rooftops, and on remote high ground, requiring emergency rescue. The storm left thousands homeless and around 150 dead in the country, while monetary losses totaled $12 million. Flooding and strong winds reached into northeastern Nicaragua, though damage was much less widespread than in neighboring Honduras.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The hurricane originated over the southwestern Caribbean Sea, where, on October 17, a broad and immature low pressure system was noted. The hurricane forecast center in Jacksonville, Florida issued its first advisory on the storm late on October 20, following ship reports of winds approaching and exceeding gale-force.[1] Contemporary reanalyses of the storm have determined that it organized into a tropical depression on October 18, then drifted toward the east, turning north-northeastward as it strengthened into a tropical storm early the next day.[2] Due to low environmental air pressures and the large size of the cyclone, intensification was gradual as the storm approached Jamaica, eventually making landfall on the eastern side of the island, just west of the Morant Point Lighthouse, at 13:00 UTC on October 21. The system came ashore with a central pressure of 995 hPa (29.4 inHg), suggesting maximum winds of 60 mph (100 km/h).[3] After emerging into the waters between Jamaica and Cuba, the storm slowed in forward speed, continued to intensify, and curved northwestward toward southeastern Cuba. The storm attained the equivalent of Category 1 hurricane status on the current-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale early on October 22, while meandering just off the coast of Cuba.[1][2]

At around 18:00 UTC on October 22, the hurricane made landfall near Santiago de Cuba at its initial peak intensity, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h).[3] It started weakening early the next day after encountering the Sierra Maestra mountain range and moving southwestward, away from the coast. Steered by persistent high-pressure ridging over the eastern United States and western Atlantic, the cyclone would maintain this highly unusual path for the remainder of its duration in open waters.[1] It brushed Cuba's Cape Cruz and deteriorated to a tropical storm before passing relatively close to the western tip of Jamaica.[2][3] On the morning of October 24, the barometer aboard a ship in the storm's eye fell to 988 hPa (29.2 inHg), its lowest recorded pressure. The ship measured winds outside of the lull only up to 46 mph (74 km/h),[3] but the storm was reintensifying, and once again achieved hurricane strength later in the day.[2] It matched its previous peak intensity at 12:00 UTC on October 25 as it approached Cabo Gracias a Dios on the border of Honduras and Nicaragua.[3] Shortly thereafter, the hurricane crossed the Honduran coast for its final landfall.[2][3] The mountainous terrain of Central America worked to diminish the storm, which curved westward and steadily lost force, though observation of its decay was minimal.[1][3] The cyclone likely dissipated on October 27 over Guatemala.[2]

Impact

The hurricane affected Jamaica, Haiti, Cuba, Honduras, and North Nicaragua along its unusual path, killing an estimated 2,150 people.[4]

Jamaica

| Country | Total deaths | Total damages | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamaica | 3 | $2.5 million | ||||||

| Cuba | 4 | $500,000 | ||||||

| Haiti | ~2,000 | $1 million | ||||||

| Honduras | ~150 | $12 million | ||||||

| Sources cited in text. | ||||||||

Parts of eastern Jamaica began to experience strong northeasterly winds early on October 20, and the parishes of Saint Thomas, Portland, and Saint Mary ultimately bore the brunt of the storm.[3] Heavy rainfall swelled rivers and triggered landslides;[5] the ensuing floods destroyed bridges, inundated many homes, and necessitated the rescue of trapped individuals.[6] With telegraph communications cut to the hardest-hit areas and roads left impassable, the degree of destruction was initially uncertain, though it was described as "extensive".[7][8] The storm took a heavy toll on agriculture (already compromised from the effects of another hurricane less than a month earlier), with banana plantations in particular sustaining heavy damage.[3][7] Losses to fruit crops in the nation totaled an estimated $2,500,000.[9]

The storm reportedly killed three people on the island.[9] An unidentified schooner capsized off Port Antonio with all hands lost,[1] in spite of efforts to rescue the imperiled crew.[8] One modern source recounts that the crew numbered 31,[10] but this figure was not widely reported. The USS Houston, underway with President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt, averted its course after encountering adverse conditions.[6]

Cuba and Haiti

In advance of the hurricane's landfall in Cuba, businesses were closed. Railways worked to secure non-essential trains, and residents of vulnerable coastal towns, including Caimanera, fled their homes in search of safer ground.[11][12] The hurricane subjected eastern parts of the island to intense gales, measured at over 70 mph (110 km/h) at Santiago de Cuba before the anemometer failed.[1] The northern coast of the island around Nipe Bay also endured strong winds as high as 58 mph (93 km/h).[3] Winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) were recorded at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, though the effects there were generally light. Closer to the hurricane's center, in Santiago de Cuba, about 100 homes sustained complete structural failures.[11][13] The prolonged nature of the storm hampered search and rescue efforts amid the rubble.[14] Winds strew debris around the city,[11] blocking its streets.[6] A hospital and a power plant both suffered roof failure.[14] Electricity in Santiago de Cuba was preemptively turned off as conditions worsened,[12] contributing to regional power outages.[11]

Significant flooding occurred after the Cauto River overflowed it banks,[14] making driving impossible.[13] The storm severed communications between towns in eastern Cuba after bringing down telephone and telegraph wires.[14] Apart from seven structures ruined in the Guantánamo area,[13] there was less destruction in many locations than initially feared.[9] There were reports of three fatalities in Caimanera, and one person died in Santiago de Cuba.[9] At least 29 individuals were treated for storm-related injuries.[11][13] Damage assessments in the immediate aftermath of the storm placed monetary damages in Cuba at $500,000.[13] In the aftermath, a public curfew was issued for Santiago de Cuba, forcing residents to remain indoors after 8 pm. To prevent looting, troops patrolled streets and vulnerable locations, such as banks.[11] Supplies of bread and milk ran short following the hurricane.[14]

The greatest disaster occurred in southern Haiti, where as many as 2,000 people died,[1] possibly more.[15] The towns of Jacmel and Jérémie—both on the Tiburon Peninsula—were devastated by catastrophic freshwater flooding after days of torrential rains. The entire peninsula, already remote in its own right, was isolated for a time, ensuring only scant detail of the disaster reached the outside world.[16] Information was initially relayed to the capital city of Port-au-Prince by a single aircraft.[17][18]

Populations of valley villages were believed to have been wiped out as rains sent the streams from the channels, demolishing the frail, thatched huts of the natives.

The Bismarck Tribune, October 28, 1935[19]

The hurricane crippled infrastructure, blocking roads throughout the area and destroying a hydroelectricity plant in Jacmel. The town was left without power and drinking water.[16] In Jérémie, the flooding was so severe as to sweep away a large metal bridge. Hundreds of poorly constructed native houses were destroyed on the Tiburon Peninsula, leaving thousands of survivors without homes.[19] Property damage in Haiti amounted to over $1 million.[17] Meanwhile, thousands of livestock were killed and crops were completely destroyed, prompting fears of impending famine.[16][17]

Several days after the storm, the bodies of drowning victims had been recovered by the hundreds,[20] and it was suspected many of the deceased had been washed into the sea.[18] One preliminary estimate placed the number of dead in the Jérémie area alone at 1,500,[20] suggesting the worst of the tragedy occurred there. Indeed, some modern sources have unofficially referred to the storm as Hurricane Jérémie.[10] The Haitian government worked to bring emergency supplies and relief workers, at least partially by way of ship, to the flood-stricken region. As little was known about the extent of losses, officials rushed to restore communications with the disaster area.[17]

Central America

After clearing the Greater Antilles, the hurricane ravaged parts of Honduras. Banana plantations suffered extensively,[1] causing the United Fruit Company about $6 million in losses. As in Haiti, the hardest hit areas of Honduras were cut off from the nation's capital of Tegucigalpa.[21] Severe river flooding wrought widespread destruction, especially around La Ceiba and throughout the Cortés Department.[22] Many towns were inundated by up to 7 ft (2.1 m) of water.[23] According to one source, the Ulúa River "officially" rose some 50 ft (15 m) from its normal height near Chamelecón,[24] where the flood left 800 families homeless.[23] Many hundreds of individuals were stranded by raging flood waters in the Cortés region, clutching to trees and rooftops as they awaited uncertain rescue.[25] Even after rescue boats brought many residents of Chamelecón to safety, a third of the population remain trapped.[23]

The rampant Cangrejal River reportedly obliterated an entire suburban community further east, near La Ceiba,[26] while the Aguán River burst its banks at Trujillo and killed numerous plantation workers. By October 29, the bodies of 70 flood victims had been recovered at Corocito in Colón.[27] Torrential rains extended into Tegucigalpa, causing urban flooding.[22] Just to the northeast, in San Juancito, a large landslide took the lives of at least three people.[24] Overall, the hurricane inflicted about $12 million in damage across Honduras (including the agricultural impacts),[21] resulted in about 150 deaths,[1] and destroyed the homes of thousands of residents.[23] The floods were considered to be among the worst in the country's history.[21][28] Almost immediately after the passage of the storm, a wide area of Honduras experienced strong earthquake activity.[29]

Damaging, but less expansive, floods also occurred in parts of extreme northeastern Nicaragua around the Mosquito Coast.[1] The Coco River, which constitutes a large portion of the Honduras–Nicaragua border, swelled 40 ft (12 m) as observed about 140 mi (230 km) upstream of its mouth.[23] Banana farms were heavily damaged around Cabo Gracias a Dios, occupied by both nations, and according to early reports in that area, all but a handful of dwellings were destroyed. In spite of the flooding and hurricane-force winds, timely warnings prevented fatalities locally.[30][31]

See also

- List of Cuba hurricanes

- Hurricane Gordon (1994), which killed 1,000–2,000 in Haiti

- Hurricane Mitch (1998), which created unprecedented flooding in Honduras

- Hurricane Lenny (1999), notable for its atypical path

- List of deadliest Atlantic hurricanes

References

- McDonald, W. F. (October 1935). "The Caribbean Hurricane of October 19–26, 1935" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 63 (10): 294–295. Bibcode:1935MWRv...63..294M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1935)63<294:tchoo>2.0.co;2. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- National Hurricane Center Hurricane Research Division (2012). "Easy-to-Read HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- National Hurricane Center Hurricane Research Division (2011). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- National Hurricane Center Hurricane Research Division (May 7, 2012). "Re-analysis of 1931 to 1935 Atlantic hurricane seasons completed" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- "Caribbean Storm Sweeps Islands". The North Adams Transcript. Associated Press. October 23, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Hurricane in Cuba Results in Heavy Loss". The San Bernardino County Sun. Associated Press. October 23, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- "Eastern Part of Jamaica Hit by Gale". The News-Herald. United Press. October 31, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Entire Crew of Schooner Believed Lost in Storm". The Sandusky Register. Associated Press. October 23, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Cuba Clearing Storm Debris". The Racine Journal-Times. Associated Press. October 23, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014. (subscription required)

- Longshore, David (2008). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones. Infobase Publishing. p. 273. ISBN 9780816062959. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- "Cuba Suffers Under Force of Hurricane". The Cornell Daily Sun. Associated Press. October 23, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- Garcia, Alberto (October 22, 1935). "Eastern Cuba Hit by Storm". The Ironwood Daily Globe. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Hurricane on Way Out to Sea". The Olean Times-Herald. October 23, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Hurricane Takes Toll of Life and Property in Cuba". The Waco News-Tribune. United Press. October 23, 1935. Retrieved June 15, 2014. (subscription required)

- Emanuel, Kerry (2005). Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes. Oxford University Press. p. 265. ISBN 9780199727346.

- "Hundreds Perished When Peninsula of Haiti Storm Swept". The Zanesville Times-Recorder. United Press. October 27, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "1500 Feared Dead in Haiti Flood". The Salt Lake Tribune. United Press. October 27, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Toll of Hurricane Mounts to 2000 in Haiti". Albuquerque Journal. Associated Press. October 28, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Haiti Storm Death Toll Reaches 2,000". The Bismarck Tribune. Associated Press. October 28, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Heavy Life Loss by Haiti Storm". The Helena Independent. Associated Press. October 27, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- Pickard, Edward W (November 8, 1935). "News Review of Current Events the World Over". The Bode Bugle. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Haiti Heaviest Loser in Hurricane; Thousands Homeless and Hungry". Associated Press. October 28, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "2,000 Dead or Missing in Haiti Hurricane; Thousands Homeless". The Daily Inter Lake. Associated Press. October 28, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Deaths in Honduras". Montana Standard. Associated Press. October 28, 1935. Retrieved June 17, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Many Trapped by High Water in Honduras". The Daily Mail. Associated Press. October 29, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Hurricane Takes 1,500 Lives". The Olean Times-Herald. October 28, 1935. Retrieved June 6, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Peril by Flood in Honduras". The Helena Independent. Associated Press. October 29, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Honduras Flood is Worst in its History". Alton Evening Telegraph. Associated Press. October 31, 1935. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Honduras Flood Damage Estimated at $12,000,000". The Kokomo Tribune. Associated Press. October 31, 1994. Retrieved June 16, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Storm Devastates Nicaragua Region". The San Bernardino County Sun. Associated Press. October 29, 1935. Retrieved June 18, 2014. (subscription required)

- "Haiti Ravaged by Floods". The Lincoln Star. United Press. October 27, 1935. Retrieved June 18, 2014. (subscription required)