1910 Atlantic hurricane season

The 1910 Atlantic hurricane season was a fairly inactive season, with only five storms. Three of those systems, however, grew into hurricanes and one became a major hurricane. The season got off to a late start with the formation of a tropical storm in the Caribbean Sea on August 23. September saw two storms, and the final tropical cyclone—Hurricane Five—existed during October. All but one of the storms made landfall, and the only cyclone which remained at sea had some effects on the island of Bermuda.

| 1910 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 7, 1910 |

| Last system dissipated | October 21, 1910 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Cuba |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 924 mbar (hPa; 27.29 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 5 |

| Hurricanes | 3 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | >100[note 1] |

| Total damage | $1.250 million (1910 USD) ([note 2]) |

| Related articles | |

The season's first storm had limited reported impacts on land, and the subsequent system caused more severe damage in southern Texas and northern Mexico. Hurricane Three dropped torrential rainfall on Puerto Rico before striking the same region as the previous cyclone. Hurricane Four bypassed Bermuda to the east, where some property damage was reported. Hurricane Five was the most catastrophic storm of the season, buffeting western Cuba for an extended period of time as it slowly executed a counterclockwise loop. Death tolls from the hurricane are estimated in the hundreds.

In addition to the five official tropical storms, a disturbance in the middle of September that tracked from east of the Lesser Antilles to off the coast of Canada was studied for potential classification. Despite producing gale-force winds, the system was likely extratropical in nature, and any time it may have spent as a tropical storm was brief.[1]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 64. ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[2]

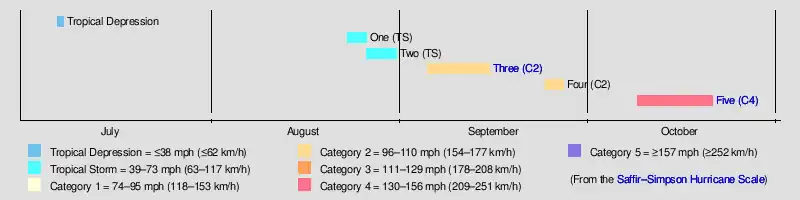

Timeline

Systems

July tropical depression

Historical weather maps indicate that a tropical depression developed well east of the Lesser Antilles on July 7. However, the depression likely dissipated by July 8, as its existence could not be confirmed beyond that day.[3]

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 23 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); |

The first tropical cyclone of the season developed on August 23, in the eastern Caribbean Sea.[4] Not believed to have strengthened further, the storm tracked west-northwestward and struck southwestern Hispaniola. It quickly weakened to a tropical depression as it turned more toward the northwest and crossed northern Cuba. On August 26, the depression passed through the Bahamas, east of the Florida Peninsula. Heading due north, the storm had transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by the next day.[5] An area of high pressure to the north and east of the storm was said to have prevented it from recurving out to sea,[4] and the cyclone skirted the eastern coast of North Carolina before being listed as dissipated east of the Delmarva Peninsula. The storm reportedly caused heavy precipitation on August 29 and 30 in Georgia and the Carolinas, while ships at sea reported high winds, rough seas and heavy rainfall.[5]

Tropical Storm Two

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – August 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); |

On August 26, a tropical depression formed in the central Gulf of Mexico.[4][5] It drifted westward for several days, and by August 30 it intensified into a tropical storm while turning more southwestward. The storm peaked in intensity as a weak tropical storm shortly thereafter.[5] On August 31 the storm moved inland near the mouth of the Rio Grande,[4] and weakened as it swept inland.[5] Advisories were issued for coastal areas before which strong winds and high tides affected the Texas coast. The cyclone inflicted some property damage in the Brownsville area.[4] Winds unroofed houses at Port Isabel and destroyed some Mexican huts. The storm also blew fishing craft aground. No initial reports of fatalities were received,[6] but two towns were left cut off from communication with Brownsville.[7]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 5 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane San Zacarias of 1910

A tropical storm developed east of the Leeward Islands on September 5 and quickly became the season's first hurricane. It continued westward through the islands and is estimated to have attained winds corresponding to Category 2 status on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.[5] On the night of September 6, San Zacarias Hurricane passed south of Puerto Rico; winds blew up to 72 mph (116 km/h) at San Juan.[8][9] The hurricane weakened somewhat on September 7 as it skirted the southern coast of Hispaniola, and curving northwestward, it passed along northern Jamaica. On September 10, it moved through the Yucatán Channel, restrengthening upon emerging into the Gulf of Mexico.[5] Now on a northwesterly course,[9] the storm reached its peak windspeeds on September 12.[5] Two days later, it made landfall along the Texas coast.[9]

The storm dropped torrential rainfall on Puerto Rico, amounting to 13 in (330 mm) in a period of 12 hours at one location. Rivers swelled to "unprecedented" levels, and the hurricane resulted in "great havoc" to telephone and telegraph wires on the island.[9] The United States Weather Bureau issued extensive warnings in association with the storm. High tides occurred along the coasts of Texas and Louisiana, accompanied by heavy rainfall.[9] A large storm surge raised the water level at Corpus Christi to its highest in years and completely inundated Padre Island,[1] where barometers recorded pressures as low as 28.50 inHg (965.12 mb) on the southern half of the island.

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); |

In the Atlantic hurricane database, the fourth hurricane of the season is listed as having formed on September 24, several hundred miles southeast of Bermuda. Strengthening, the storm moved northwestward and is estimated to have peaked with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). It gradually turned toward the northeast as it bypassed Bermuda to the east. On September 27, it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and turned eastward. It dissipated several days later.[5] The storm caused some damage to property on the island, and blew a barque aground.[1]

Hurricane Five

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 9 – October 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 924 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Cuba Hurricane of 1910

The final storm of the season formed in the extreme southern Caribbean on October 9, and steadily intensified as it moved northwestward. Shortly after making landfall on the western tip of Cuba, the storm peaked as a severe hurricane corresponding to Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale and completed a counterclockwise loop.[5] During its loop, the pressure in its eye dropped to 924 mb (27.29 inHg)[5] with an unofficial reading of 917.71 mb (27.10 inHg) aboard the steamship Brazos.[1] The cyclone began weakening and tracking toward the United States, and moved ashore near Fort Myers, Florida, with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) corresponding to those of a strong Category 2 hurricane.[5] After moving through the state, it hugged the coast of the Southeastern United States on its way out to sea.[10] Due to the storm's tight and poorly documented loop, initial reports suggested that it was actually two separate cyclones that developed and affected land in rapid succession. Its track was subject to much debate at the time, and eventually it was identified as a single storm. Additionally, observations on the event resulted in a greater understanding of other weather features that took similar paths.[10]

In Cuba, the storm was considered one of the most severe natural disasters in the island's history.[11] Damage was extensive, and thousands of peasants were reportedly left homeless.[12] Throughout Florida, the storm also had widespread, yet more moderate, impacts, including damage to houses and the flooding of low-lying land.[10][13] The pressure at Fort Myers dropped to 28.20 inHg (954.96 mb) during the storm.[1] Although total monetary damage from the storm is unknown, estimates of losses in Havana, Cuba, exceed $1 million and in the Florida Keys, $250,000 (1910 USD).[14][15] At least 100 deaths occurred in Cuba alone.[16]

See also

Notes

- Death tolls from Hurricane Five vary widely; however, it is known that at least 100 deaths resulted from the storm.

- This damage figure is derived from the sum of damage of estimates at two locations affected by Hurricane Five, and is likely not representative of the season's total damage.

References

- Jose Fernandez Partagas & Henry F. Diaz (1999). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources Part VI: 1909-1910 (PDF). Climate Diagnostics Center. p. 3. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- Edward H. Bowie (August 1910). "Weather, Forecasts and Warnings for the Month" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 38 (8): 1297. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- Hurricane Specialists Unit (2010). "Easy to Read HURDAT 1851–2009". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- "Shores of Texas Swept by Fierce Gulf Storm". The Herald-Journal. August 31, 1910. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- "Gulf Storm Increases; Government Launch May Be Lost -- Coast Points Are Cut Off" (PDF). The New York Times. August 31, 1910. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- Frank Mújica-Baker. Huracanes y Tormentas que han afectadi a Puerto Rico (PDF). Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Agencia Estatal para el manejo de Emergencias y Administracion de Desastres. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Edward H. Bowie (September 1910). "Weather, Forecasts and Warnings for the Month" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 38 (9): 1456. Bibcode:1910MWRv...38.1456B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1910)38<1456:WFAWFT>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. p. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0.

- "Cyclone Works Havoc in Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. October 18, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- "The Hurricane in Cuba". The Manchester Guardian. October 17, 1910. p. 7.

- "West Indian Storm and Cold Wave May Meet". The Galveston Daily News. October 19, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved August 27, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Cyclone in Cuba". The Scotsman. October 18, 1910.

- Charles F. von Herrmann (October 1910). "District No. 2, South Atlantic and East Gulf States" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 38 (10): 1456. Bibcode:1910MWRv...38.1456B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1910)38<1456:WFAWFT>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- David Longshore (2008). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones. Checkmark Books. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8160-7409-9.