10-inch gun M1895

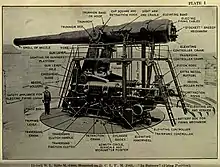

The 10-inch Gun M1895 (254 mm) and its variants the M1888 and M1900 were large coastal artillery pieces installed to defend major American seaports between 1895 and 1945. For most of their history they were operated by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. Most were installed on disappearing carriages, with early installations on barbette mountings.[5] All of the weapons not in the Philippines (except four guns in Canada) were scrapped during World War II. Two of the surviving weapons were relocated from the Philippines to Fort Casey in Washington state in the 1960s.

| 10-inch Gun M1895 | |

|---|---|

10-inch gun M1895MI on disappearing carriage M1901, Fort Casey, Whidbey Island, Washington | |

| Type | Coastal artillery |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1895–1945 |

| Used by | United States Army Canada |

| Wars | World War I, World War II |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Watervliet Arsenal |

| Designed | 1888 |

| Manufacturer | Watervliet Arsenal, Bethlehem Steel, possibly others |

| Variants | M1888, M1895, M1900 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 67,200 pounds (30,500 kg) (M1888MI and M1888MII)[1] |

| Length | 30.6 feet (9.3 m) |

| Barrel length | 34 calibers 340 inches (8.6 m) |

| Shell | separate loading, 617 pounds (280 kg) AP shot & shell, 510 pounds (230 kg) HE[2] |

| Caliber | 10 in (254 mm) |

| Breech | Interrupted screw, De Bange type |

| Carriage | M1893 barbette, M1894, M1896, or M1901 disappearing, most manufactured by Watertown Arsenal[3] |

| Elevation | disappearing: 12° |

| Traverse | disappearing: 170° (varied with emplacement) |

| Maximum firing range | disappearing: 14,700 yards (13,400 m)[4] |

| Feed system | hand |

History

In 1885, William C. Endicott, President Grover Cleveland's Secretary of War, was tasked with creating the Board of Fortifications to review seacoast defenses. The findings of the board illustrated a grim picture of existing defenses in its 1886 report and recommended a massive $127 million construction program of breech-loading cannons, mortars, floating batteries, and submarine mines for some 29 locations on the US coastline. Most of the Board's recommendations were implemented. Coast Artillery fortifications built between 1885 and 1905 are often referred to as Endicott Period fortifications. The Watervliet Arsenal designed the gun and built the barrels. A few of the first guns were mounted on low-angle M1893 barbette carriages. Subsequently, most of the guns were mounted on M1894, M1896, or M1901 disappearing carriages; when the gun was fired, it dropped behind a concrete and/or earthen wall for protection from counter-battery fire. Detailed descriptions of the M1888 weapon and Buffington–Crozier disappearing carriage are in the US Army's Artillery circular 1895, pp. 183–195, along with a description and illustration of a "modified Gordon" disappearing carriage, an experimental type. Detailed parts lists for the M1888M1 weapon and supporting equipment are in the Ordnance supply manual by George L. Lohrer, United States Army, Ordnance Dept, 1904, pp. 47–113.

After the Spanish–American War, the government wanted to protect American seaports in the event of war, and to protect newly gained territory, such as the Philippines and Cuba, from enemy attack. A new Board of Fortifications, under President Theodore Roosevelt's Secretary of War William Taft, was convened in 1905. Taft recommended technical changes, such as more searchlights, electrification, and in some cases fewer guns in particular fortifications. The seacoast forts were funded under the Spooner Act of 1902 and construction began within a few years and lasted into the 1920s. The defenses of the Philippines on islands in Manila Bay and Subic Bay were built under this program.[6]

Experimental gun

A 10-inch "depressing gun" M1896 on an M1894 disappearing carriage was mounted in an experimental battery at Fort Monroe, Virginia in the northeast bastion. The battery was operated from 1900 to 1908, and the concrete portions remain in place.[7]

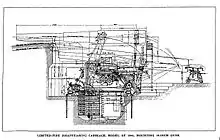

Railway mounting

After the American entry into World War I, the Army recognized the need for large-caliber railway guns for use on the Western Front. Among the weapons available for this were 129 10-inch guns, to be removed from fixed defenses or taken from spares. Thirty-six Schneider-type sliding-mount railway carriages for 10-inch guns were contracted to be manufactured by the Marion Steam Shovel company and delivered to France for finishing by March 1919. Of these, eight sets were shipped prior to the Armistice, then were returned to the US where 22 of the 36 originally contracted mountings were completed.[8][9] A detailed description of the railway mounting is given in Railway Artillery, Vol. I by Lt. Col. H. W. Miller, USA.[10] The range of the railway weapon was 24,700 yards (22,600 m) at 36° elevation.[11] Guns not mounted were returned to coastal defenses after the war; in the late 1920s the 10-inch railway gun was declared obsolete and the mountings scrapped.[12]

World War II

In April–May 1941 eight M1888 guns were sent to Canada under Lend-Lease for use in coast defenses there. These included three guns from Battery Harker, Fort Mott on disappearing carriages,[13] three guns from Battery Quarles, Fort Worden on barbette carriages,[14] and two guns from Battery Revere, Fort Flagler on barbette carriages.[15] Two of the Fort Mott disappearing guns were deployed at Fort Cape Spear, St. John's, Newfoundland and remain there. The remaining disappearing gun from Fort Mott and one barbette gun from Fort Flagler were deployed at Fort Prével on the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec. Two of the barbette guns from Fort Worden were deployed to Fort McNutt on McNutts Island, Nova Scotia and remain there, although only part of one still exists. The remaining two barbette guns from Forts Flagler and Worden were deployed at Wiseman's Cove, Botwood, Newfoundland and no longer exist.[16]

Along with other coast artillery weapons, some of the 10-inch guns in the Philippines saw action in the Japanese invasion in World War II. Since they were positioned against a naval attack, they were poorly sited to engage the Japanese, and the open mountings were vulnerable to air and high-angle artillery attack.

In 1940–44, 16-inch gun batteries were constructed at most harbor defenses, and essentially all 10-inch guns not in the Philippines were scrapped 1943–44.

Surviving examples

Nine 10-inch guns (one partial) remain at four locations.[17]

1. Two 10-inch Guns M1895MI (#25 & #22 Watervliet) on Disappearing Carriages M1901 (#14 & #16 Watertown), Battery Grubbs, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines. The guns lie behind their mountings, since they were fired while disconnected from the carriages to deny use of them to the Japanese forces.

2. One 10-inch Gun M1895MI (#20 Watervliet) (spare gun), Battery Grubbs, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

3. Two 10-inch Guns M1895MI (#26 & #28 Watervliet) on Disappearing Carriages M1901 (#13 & #15 Watertown), Battery Worth, Fort Casey, Coupeville, WA (guns moved in the 1960s from Battery Warwick, Fort Wint, Grande Island, Subic Bay, Philippines)

4. Two 10-inch Guns M1888 (#41 & #3 Watervliet), Fort Cape Spear, St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada (guns moved in World War II from Battery Harker, Fort Mott, New Jersey)

5. One 10-inch Gun M1888 (#12 Watervliet) on Barbette Carriage M1893 (#11 Watertown) (with partial remains of other gun (#37) and carriage (#1)), Fort McNutt, McNutts Island, Nova Scotia, Canada (guns moved in World War II from Battery Quarles, Fort Worden, WA)

See also

- Coastal artillery

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

- Coast Artillery fire control system

Weapons of comparable role, performance and era

- 10"/40 caliber gun Mark 3 - contemporary US Navy weapon

- BL 9.2-inch Mk IX – X naval gun - contemporary British naval and coast defense weapon

- Canon de 240 L Mle 1884 - contemporary French coast defense, siege, and railway weapon

References

- Artillery Circular 1895, p. 184

- Berhow, p. 61

- Berhow, pp. 130–155

- Berhow, p. 61

- Coast Defense Study Group fort and battery list

- Berhow, Mark A. and McGovern, Terrance C., American Defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay 1898–1945, Osprey Publishing Ltd.; 1st edition, 2003; pages 7–8.

- Northeast Bastion Battery at Fort Monroe, FortWiki.com

- US Army Railway Artillery in World War I

- Crowell, Benedict, America's Munitions 1917–1918, pp. 96–97

- Miller, H. W., LTC, USA Railway Artillery, Vols. I and II, 1921, Vol. I, pp. 156-182

- Handbook of Ordnance Data, 15 November 1918, pp. 97–108

- Hogg, Ian V. (1998). Allied Artillery of World War I. Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press, Ltd. pp. 140–141. ISBN 1-86126-104-7.

- Battery Harker article at Fort Wiki.com

- Battery Quarles article at FortWiki.com

- Battery Revere article at FortWiki.com

- Berhow, p. 225

- Berhow, p. 230

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Second Edition. CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Miller, H. W., LTC, USA (1921). Railway Artillery, Vol. I. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 156–182.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (Vol. II at this link)