Zhang Sengyou

Zhang Sengyou (Chinese: 張僧繇, Zhāng Sēngyóu[1]) was a famous Liang dynasty painter in the ink style in the reign of Emperor Wu of Liang.

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

His birth and death years are unknown, but he was active circa 490–540. He was from Wu Commandery (around present-day Suzhou, Jiangsu).

Background and reputation

Zhang was a member of Zhang clan of Wu, one of the four prominent clans in Wu Commandery.

According to Tang dynasty art critic Zhang Yanyuan's "Notes of Past Famous Paintings", Zhang served as an official during the reign of Emperor Wu of Liang. He was the director of the imperial library and was also in charge of any painting related affairs in the court of Emperor Wu. Later, Zhang served the country as the general of right flank army and the governor of Wuxing Commandery.[2] His works were rated the finest quality by Zhang Yanyuan. He also listed Zhang's artistic style as one of the four "Standards" of the traditional Chinese paintings; the other three artists were Gu Kaizhi, Lu Tanwei and Wu Daozi.[3]

Yao Zui, an art critic in Chen Dynasty, described Zhang as a diligent painter who paints "without the notion of day and night".[4]

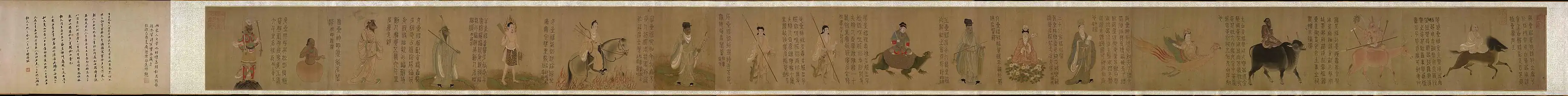

Zhang was especially skillful in depicting human or animal figures. According to the History of the Southern Dynasties, Zhang painted a portrait for Prince Wuling, one of the sons of Emperor Wu of Liang. After viewing his son's portrait, the Emperor was amazed by the verisimilitude of Zhang's painting.[5][6]

Buddhism with all its iconography, came to China from India, bringing with it to China a Western influence at one remove. Pictorial forms thus acquired a certain three-dimensional quality. Zhang Sengyou, working in the early sixth century, painted large murals of Buddhist shrines in Nanjing. He was one of the first to use these influences with happy results.[6] He was also well known for landscapes, especially snow scenery, with a reputation for the so-called "boneless" technique (mogu).

Zhang is also associated with a famous story. It is said that one day, having painted four dragons on the walls of Anle temple in Jinling, he did not mark the pupil, not by negligence but prudence. However, one person, unwilling to heed Zhang's warnings, painted in the eyes of two dragons, causing the dragons to immediately flee to heaven riding on clouds with crashing thunder. Marking the eyes of dragons opens their eyes and gives them life. The spirit is fleeting, omnipresent, so that grasping and fixing it in a painting gives his work an uncanny power of suggestion. This story, summarized in the chengyu (traditional Chinese: 畫龍點睛; simplified Chinese: 画龙点睛; pinyin: huàlóng-diǎnjīng), is used in modern Chinese as a metaphor to describe a written work or speech that lacks only a small element which would make it perfect.[1]

References

- 现代汉语词典(第七版) [A Dictionary of Current Chinese (Seventh Edition).]. 北京. Beijing: 商务印书馆. The Commercial Press. 1 September 2016. p. 564. ISBN 978-7-100-12450-8.

【画龙点睛】huàlóng-diǎnjīng 传说梁代张僧繇(yóu)在金陵安乐寺壁上画了四条龙,不点眼睛,说点了就会飞走。听到的人不相信,偏叫他点上。刚点了两条,就雷电大作,震破墙壁,两条龙乘云上天,只剩下没有点眼睛的两条(见于唐张彦远《历代名画记》)。 比喻作文或者说话时在关键地方加上精辟的语句,使内容更加生动传神。

- Notes of Past Famous Paintings. People's arts Press. 2004. ISBN 9787102030098.

- Lee, Yu-min (2001). Art History of Chinese Buddhism. p. 32. ISBN 9789571926148.

- 續畫品. Shanxi Education Press. ISBN 9787544058650.

- History of the Southern Dynasties. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. 1975. ISBN 9787101003178.

- Wan, Shengnan (2007). 魏晋南北朝文化史. Dongfang Press Center. p. 270. ISBN 9787801865823.