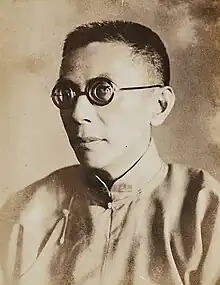

Zhang Renjie

Zhang Renjie (Chang Jen-chieh 19 September 1877 − 3 September 1950), born Zhang Jingjiang, was a political figure and financial entrepreneur in the Republic of China. He studied and worked in France in the early 1900s, where he became an early Chinese Anarchist under the influence of Li Shizeng and Wu Zhihui, his lifelong friends. He became wealthy trading Chinese artworks in the West and investing on the Shanghai stock exchange. Zhang gave generous financial support to Sun Yat-sen and was an early patron of Chiang Kai-shek. In the 1920s, he, Li, Wu and the educator Cai Yuanpei were known as the fiercely anti-Communist Four Elders of the Chinese Nationalist Party. [1]

Zhang Renjie 張人傑 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 September 1877 |

| Died | 2 September 1950 (aged 72) |

| Occupation(s) | Entrepreneur, political figure |

Early years

Zhang was born September 13, 1877, in Wuxing, Zhejiang, but his family's ancestral home was Nanxun, Zhejiang Province, where his grandfather was a prosperous salt and silk merchant. Zhang's father, Zhang Baoshan (张宝善, 1856–1926), developed the family business, and married into a family of Shanghai silk compradores which had extensive contacts among Western businesses. [2]

As a boy, Zhang was adventurous and bright; he enjoyed both riding horses and calligraphy, memorized classics, and was especially good at Go. As a child he suffered from a form of arthritis, which continued to affect him for the rest of his life, and an eye condition which eventually required him to wear dark glasses. Yet he was a sociable child. So self-confident was he that he gave himself the name "Renjie," meaning "outstanding personality." Zhang's grandfather, convinced that Renjie should become an official, purchased the office of "Expectant Daotai" for him. The family arranged a marriage for him with Yao Hui, and the first of his five daughters was born in 1901. [2]

On a trip to Beijing in 1901 to arrange a suitable posting for himself as "Expectant Daotai," Zhang met the equally well-placed and adventurous Li Shizeng, son of a high Qing official. The two discovered that they shared a dissatisfaction with the state of Chinese politics and society. When in 1902 Li was appointed as attache on the staff of the Minister to France, Sun Baoqi, Zhang used his family influence to join him and be appointed as "Third Secretary." After stopping over in Shanghai to meet Wu Zhihui, who was by then a well-known anti-Manchu revolutionary, Zhang and Li arrived in Paris as part of Sun's delegation on December 17, 1902. Zhang's wife, Yao Hui, accompanied him. Li quickly resigned his official position to study French and biology, but Zhang did not resign until 1905. [3]

Paris, anarchism, and revolution

In Paris he established the Ton-ying Company (Chinese: 通运公司; pinyin: Tongyun Gongsi), with a gallery on the Place de la Madeleine, which imported Chinese tea, silk, and art. This was the first of its kind in France, and employed, among others, C.T. Loo, who was to become one of the most influential dealers of Chinese art. With the financial assistance of $300,000 Chinese dollars from his father, the firm was the basis of Zhang's own considerable fortune. [4] Ton-ying remained a family business branching out to New York from its original base in Paris and its source in Shanghai. Because of Zhang’s position in China, the Company was able to source high quality works of art directly, including items from the old Imperial Collection. Although Zhang later dealt extensively on the Shanghai stock exchange, a great deal of his wealth and therefore the financing of the Nationalist (then Tongmenghui) cause, came from the profits created by the Ton-ying Company. [5]

Li soon introduced Zhang to the doctrines of Anarchism and they began to apply them to analyzing the situation in China. Zhang told friends of the anti-religion and anti-family theories which he had adopted. He also opposed traditional ideas of sex: "It is obvious," he told them, "the reason why society is divided along sexual lines is because of traditional customs.... It's not impossible to reform them." Zhang's interest in anarchism later cooled, however, and he was probably more attracted by its aura of science and iconoclastic social reform than its political side. [6]

On a trip to London in 1905, Zhang renewed his friendship with Wu Zhihui, who was nearly ten years older than Li and Zhang, and a deeper scholar. Backed by Zhang's money, the three formed the Shijie she (The World), a publishing house for radical social ideas. On a steamship returning from China to Europe in 1906, Zhang met and was entranced by Sun Yat-sen, the anti-Manchu revolutionist, giving him the first of many substantial contributions. The two established a code for Sun to use if he needed money: "A" meant send $10,000 Chinese dollars, "B" meant send $20,000, and so forth.[7] On his return to Paris, Zhang led Wu and Li to join Sun's Tongmenghui, the more politically radical of the anti-Manchu groups. Zhang had been sworn into the society by Hu Hanmin and Feng Ziyou, two of Sun's important lieutenants (in view of his attacks on religion, they allowed him to omit the oath "by heaven").[6]

The three anarchists —Zhang, Li, and Wu — established a relationship which lasted for the rest of their lives. In 1908, they started a journal, Xin Shiji (New Century), titled La Novaj Tempaj in Esperanto, funded by Zhang and edited by Wu. Another major contributor was Chu Minyi, a student from Zhejiang who accompanied Zhang back from China and would help him travel in the years to come. The journal translated radical French thinkers and introduced Chinese students in France to the history of radicalism, especially the anarchist classics of Peter Kropotkin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Élisée Reclus. They were especially impressed by their conversations with Jean Grave, who had spent two years in prison for publishing "Society on the Brink of Death" (1892) an anarchist pamphlet. But Zhang, who continued to travel back and forth to China, did not have money enough to finance both Sun Yat-sen and the journal, which ceased publication in 1910. [8]

When the Revolution of 1911 broke out, Zhang returned to China. He was one of the organizers of the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement, which sent worker-students to France. Though he did not take up Sun's offer to be minister of finance, he continued to give financial support to Sun and his party, which became especially important when Sun was forced to flee to Japan as Yuan Shikai took control of the new republic. Zhang used his money and charm to make friends in many parts of Shanghai society, including the underworld, and especially among those from Zhejiang province.[9]

Relations with the Nationalist Party and Chiang Kai-shek

During these years, Zhang did well on the Shanghai stock market and shared his earnings with Sun and the emerging Nationalist Party (GMD). His GMD friends from Zhejiang included Chen Qimei, a patron of the then unknown Chiang Kai-shek. When Chen was assassinated, apparently on orders of Yuan Shikai, Zhang took over Chen's role as Chiang's mentor. After Yuan's death in 1916, Sun continued to rely on Zhang, and Zhang offered Chiang Kai-shek substantial financial help, personal advice, and key political backing. On a visit to Zhang's home, Chiang met Ah Feng (Jennie), a friend of Zhu Yimin, Zhang's second wife, and immediately determined to marry her. When Ah Feng's family commissioned a detective report which found that Chiang was not only unemployed but also had a wife and concubine, Zhang reassured them that he would vouch for the young man's good intentions. At their wedding, Zhang delivered a speech wishing the couple happiness and success. [10] Zhang also hit it off with Chen Lifu, another of Chiang's most important advisers and supporters, also from Zhejiang, organizer of the right-wing CC Clique [11]

In 1923, Sun invited Soviet advisors to reorganize the Nationalist Party and incorporate the Chinese communists (First United Front), setting up an internal rivalry between the left and the right wings. Zhang, as a right-wing leader, was elected to the Central Executive Committee (CEC), along with Li Shizeng, Wu Zhihui, and Cai Yuanpei, all from Zhejiang. They became known as the GMD's “Four Elders", or Yuanlao (国民党元老), in Japanese, genrō. Chiang Kai-shek built his rise to power and subsequent long political life on his ability to skillfully using this and other groups for a certain time, then shifting his support to opposing factions to keep both friends and enemies off balance. [12]

When Sun died in 1925, Zhang was one of the witnesses to his deathbed Political Will, and was elected to the new State Council which convened in Canton. In the Zhongshan Gunboat Incident of March 1926, Chiang Kai-shek's life was supposedly endangered by a kidnapping plot. Chiang moved to suppress the Leftists, surprising many who had thought of him as a leftist, threatening a debilitating schism. Zhang counseled Chiang against identifying himself too closely with the right, and may have attempted to reconcile Chiang with the leftist Wang Jingwei, who had been his friend from their anarchists days in Europe. [13] [14]

The Four Elders were fiercely anti-Communist. Their anarchist principles led them to see the poor and uneducated as members of the Chinese nation, not members of the working class. They accused the Communists of creating class divisions and promoting class warfare. [15] The radical left wing of the party, led by Wang Jingwei, who set up its own headquarters at Wuhan, mounted a campaign with the slogan "Down With The Muddle-headed, Old and Feeble Zhang Jingjiang." Zhang remarked to his friend Chen Lifu, "if I were really muddle-headed, old, and feeble, would it be worthwhile to make the effort to knock me down?" [16] A Soviet advisor recalled that Zhang "was able to generate incredible energy in the struggle with the leftists and Communists" even though he could not walk and had to be carried upstairs in his wheelchair. [17] In April 1927, Zhang and the other Four Elders urged Chiang Kai-shek to purge the leftists and initiate the White Terror which killed thousands.[18]

At this time, a rift opened between Zhang and Chiang Kai-shek which eventually became bitter and lasted until Zhang's death. Zhang had introduced Chiang to his second wife, Jennie, who was a friend of his wife, Yimin, and had felt aggrieved when Chiang abandoned her for Soong Mei-ling. To intimates Zhang confided "a man of moral integrity should not go back on his word, let alone a state leader!" In the following years, Soong Mei-ling apparently resented Zhang for his loyalty to Jennie. She and the Zhang family did not speak to each other. In 1927, after the success of the Northern Expedition and the alliance with the wealthy Soong family, Chiang perhaps was in less need of Zhang's help, and might also have feared Zhang's growing power. Zhang as an anarchist also opposed organized religion, while Chiang converted to Christianity. [19]

The four friends from anarchist days of cultural exchange and education in France collaborated on the National Labor University, which revived two abandoned factories and used them for Work–Study. [20] Li Shizeng became chairman of the newly created Imperial Palace Museum in 1925 and was responsible for the inventory of the Imperial Collections. Zhang oversaw the first stage of the removal of more than half of the Imperial Collections to Shanghai in 1933 following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. It was during this period that many imperial works of art found their way into Western collections, through dealers such as Zhang. [5]

Chiang then asked Zhang to head the National Reconstruction Commission, whose assignment was to control the industrial sector of the economy. The Commission confiscated a number of private mines and power companies, though its influence was soon undercut by the National Economic Council headed by T. V. Soong. [18] Over the next few years, Zhang continued to play a profitable and influential role in Shanghai financial circles, sometimes in conjunction with Soong, sometimes in rivalry. [21]

Provincial government and declining influence

From November 1928 to January 1930, Zhang was governor of Zhejiang, his and Chiang Kai-shek's home province. Zhang suppressed rural unrest, perhaps to avoid the opposition of landlords and local elites to his projects for building infrastructure for the power industry, as well as heading the National Reconstruction Commission. However, in 1931, T. V. Soong took charge of economic development training and limited the powers of Zhang and his commissions. [18] Yet Zhang's ambitious plans to expand the power grid and infrastructure made some progress before the destruction in the Japanese invasion. His pet project, however, the Hangzhou Electric Plant, had to be sold to a private group because low demand and budget shortfalls. [22]

Zhang's influence on Chiang Kai-shek continued to decline and relations cooled. The Generalissimo placed men who were loyal into the Zhejiang government and undercut Zhang's authority in ways which embarrassed him. "If he wants me to hand in my resignation," Zhang asked after Chiang criticized the state of security in Zhejiang, "why should he play such an underhanded trick?" Giving the excuse that he needed to travel abroad for his health, Zhang resigned as governor in 1930. He kept his position in the National Reconstruction Commission but found that Chiang did not grant it enough money for its work. Zhang contributed 4,000 yuan of his own.[23]

It is said that when he heard the news of the Japanese attack on Shanghai in 1931, he was struck with the strength of the Chinese proverb "the strong making meat of the weak," and became a vegetarian. [24] By the mid-1930s, Zhang had largely retired from politics and pursued his artistic inclinations and began to practice Buddhism. In 1937, at the age of fifty-four, in spite of failing health and financial strains, he decided to take his family to live in Hong Kong, then left for Europe. When his brother suggested that he telegraph Chiang Kai-shek to inform him, Zhang snapped "Why should I inform him? He's not my boss! It's none of his business!" Zhang and his family settled in Riverdale, in New York City. He and Li Shizeng sometimes met to look over the Hudson River and reminisce.[25]

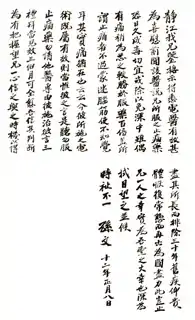

Zhang died on 3 September 1950. When his daughter, who was living in Taipei, heard the news, she did not have the courage to inform Chiang Kai-shek directly, fearing the lingering enmity between the two men. Instead, she informed Wu Zhihui, who visited Chiang at 6:00 AM the next morning. Chiang sent a telegram of condolence to the family in the United States: "You were my companion in adversity and our friendly feelings were close..." Chiang presided and wrote an inscription in his own calligraphy for Zhang's memorial service: "Deep grief for losing my teacher." He arranged for the Nationalist Party in Taiwan to send money to Zhang's family for the services in New York. [26]

Family life

Zhang was the member of an extensive family. His father, Zhang Baoshan (张宝善 1856-1926), had five children, of whom Jingjiang was the second. He married twice, first to Yao Hui 姚蕙 ( -1918). The marriage produced five daughters: Therese 蕊英 (1901?- 1950); Yvonne 芷英(1902-1975); Suzanne 芸英 (1904- 1998); Georgette (荔英 Liying; 1904-1995); Helen (菁英 Jingying 1910-2004). [27] Georgette in 1930 married Eugene Chen in Paris. [28] Helen married Robert K.S. Lim, a medical doctor from Singapore who worked with Chinese army during the war, in 1946. [29]

In 1918, Yao Hui was killed by a falling branch in Riverside Park in New York City. [30] In 1920, Zhang met and married Zhu Yimin (朱逸民 1901-1991 in Shanghai.[31] They had five daughters and two sons. [24]

Legacy and reputation

Nelson and Laurence Chang's history of the Zhang family points out that Western histories portray Zhang Jingjiang as a "menacing figure, a malign influence in the Chinese political scene." They object to Sterling Seagrave's The Soong Dynasty, for instance, which says that Zhang's disease "crippled one of his feet and thereafter gave him the lurching gait of Shakespeare's Richard III. This sinister millionaire, whom some Westerners referred to as Curio Chang and the French in Shanghai referred to as Quasimodo, became one of Chiang Kai-shek's most important political patrons." They go on to recognize that Zhang was a revolutionary who was not afraid to use violence, but that his political rivals did much to darken his reputation. [32]

Zhang was a successful investor and business man and one of his investments was a European style neighbourhood in Shanghai, Jing'an Villa, which still stands today. It can be found at 1025 Nanjing Xi Lu, in Shanghai's Jing'an district. Built in 1932, it once housed members of the Western and Chinese elite in Shanghai's International Settlement. Its European-inspired architecture stands as a reminder of the interaction between Europe and China, of which Zhang was a part.[33]

Nelson and Laurence Chang's book "The Zhangs from Nanxun" includes a family tree (page 526) which lists the East Branch of the family: descendants of Zhang Baoshan include his sons Zhang Jingjiang and Zhang Bianqun, whose eldest son the scholar Zhang Naiyan was the first Chancellor of the University at Nanjing and Chinese Ambassador to Belgium. Zhang Naiyan's daughter Jane Chang emigrated to Lynn, Massachusetts in 1949 with her husband Arthur Yau; their eldest son is poet and critic John Yau.

References

Citations

- Boorman (1967), p. 73-77.

- Chang (2010), p. 156-159.

- Chang (2010), pp. 160–161.

- Boorman (1967), p. 74.

- Pearce (2004).

- Zarrow (1990), p. 75.

- Wilbur (1976), p. 40-41.

- Zarrow (1990), p. 76-80.

- Boorman (1967), p. 75.

- Fenby (2003), p. 48-51.

- Ch'en (1994), p. 35, 38-39.

- Eastman (1991), p. 18.

- Chen (2008), pp. 177-180.

- Fenby (2003), p. 48-49.

- Zarrow (1990), p. ?? 202-203.

- Ch'en (1994), pp. 49, 62.

- Akimova (1971), p. 213, 225.

- Boorman (1967), p. 76.

- Chang (2010), p. 233-235, 259, 263.

- Chan (1991), p. 72-74.

- Coble (1980), p. 29,56, 100-101, 217, 218, 222, 223.

- Wang (2004), p. 55-56.

- Chang (2010), p. 238-242, 263.

- Boorman (1967), p. 77.

- Chang (2010), p. 259-263.

- Chang (2010), p. 266.

- Chang (2010), p. 8.

- Chang (2010), p. 216,220, 291-300, 412, 442, 513.

- Chang (2010), p. 276, 305.

- Chang (2010), p. 269-70.

- Chang (2010), p. 199.

- Chang (2010), p. 190-191.

- "Jing'an Villa". Minor Sights. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

Sources

- Akimova, Vera Vladimirovna (1971). Two Years in Revolutionary China, 1925-1927. Cambridge, MA: East Asian Research Center, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0674916012.

- Chan, Ming K. and Arif Dirlik (1991). Schools into Fields and Factories : Anarchists, the Guomindang, and the National Labor University in Shanghai, 1927-1932. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822311546.

- "Chang Jen-chieh," in Boorman, Howard L., ed. (1967). Biographical Dictionary of Republican China Volume I. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 73–77. ISBN 978-0231089586.

- Chang, Nelson, Laurence Chang (2010). The Zhangs from Nanxun: A One Hundred and Fifty Year Chronicle of a Chinese Family. Palo Alto; Denver: CF Press. ISBN 9780692008454.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ch'en, Lifu (1994). The Storm Clouds Clear over China: The Memoir of Ch'en Li-Fu, 1900-1993. Stanford, CA: Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0817992712.

- Chen, Yuan–tsung (2008). Return to the Middle Kingdom: One Family, Three Revolutionaries, and the Birth of Modern China. New York, NY: Union Square Press. ISBN 9781402756979.

- Coble, Parks M. (1980). The Shanghai Capitalists and the Nationalist Government, 1927-1937. Cambridge, MA: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University : distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674805354.

- Lloyd Eastman, "Nationalist China during the Nanking Decde," in Eastman, Lloyd (1991). The Nationalist Era in China, 1927-1949. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511572838. ISBN 9780521392730.

- Fenby, Jonathan (2003). Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the China He Lost. London: Free Press. ISBN 978-0743231442.

- Parke-Bernet Galleries (1954). Chinese Art: From the Collection of Tonying & Company, Inc., New York, Sold by Their Order: Public Auction Sale, Wednesday and Thursday, April 14 and 15 at 1:45 P.M. Catalogue / Parke-Bernet Galleries ;1511. New York, NY: Parke-Bernet Galleries.

- Pearce, Nick (2004). "Ton-Ying & Co". Chinese-Art Research into Provenance.

- Scalapino, Robert A. and George T. Yu (1961). The Chinese Anarchist Movement. Berkeley, CA: Center for Chinese Studies, Institute of International Studies, University of California. Available at The Anarchist Library.

- Wang, Shuhuai (2004). "Zhang Renjie and the Hangzhou Electric Plant". Bulletin of the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica (in Chinese). 43 (3): 1–56.

- Wilbur, C. Martin (1976). Sun Yat-Sen, Frustrated Patriot. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231040365.

- Zarrow, Peter Gue (1990). Anarchism and Chinese Political Culture. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231071383.