Zdzisław Beksiński

Zdzisław Beksiński (pronounced [ˈzd͡ʑiswaf bɛkˈɕiɲskʲi]; 24 February 1929 – 21 February 2005) was a Polish painter, photographer, and sculptor; specializing in the field of dystopian surrealism.

Zdzisław Beksiński | |

|---|---|

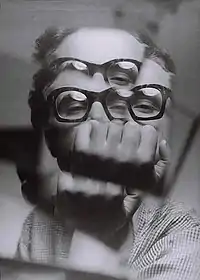

Self-portrait, 1956–1957 | |

| Born | 24 February 1929 |

| Died | 21 February 2005 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, photography |

| Awards | Order of Polonia Restituta |

| Signature | |

Beksiński made his paintings and drawings in what he called either a Baroque or a Gothic manner. His creations were made mainly in two periods. The first period of work is generally considered to contain expressionistic color, with a strong style of "utopian realism" and surreal architecture, like a doomsday scenario. The second period contained more abstract style, with the main features of formalism.[1]

Beksiński was stabbed to death at his Warsaw apartment on February 21, 2005, by a 19-year-old acquaintance from Wołomin, reportedly because he refused to lend him money.[2]

Life

Zdzisław Beksiński was born in Sanok, southern Poland. He studied architecture at Kraków Polytechnic in 1947, finishing his studies in 1952.[3] He returned to Sanok in 1955, working as a construction site supervisor, but found that he did not enjoy it. During this period, he had an interest in montage photography, sculpting, and painting. When he first started sculpting, he often used his construction site materials for his medium. His early photography was a precursor to his later paintings, often depicting peculiar wrinkles, desolate landscapes, and still-life faces on rough surfaces. His paintings often depict anxiety, such as torn doll faces, or faces erased or obscured by bandages wrapped around the portrait. His main focus was on abstract painting, although it seems his works in the 1960s were inspired by surrealism.[1]

Painting and drawing

Beksiński had no formal training as an artist. He was a graduate of the Faculty of Architecture at the Kraków Polytechnic, receiving an MSc in 1952.[2] His paintings were mainly created using oil paint on hardboard panels that he personally prepared, although he also experimented with acrylic paints. Beksiński listened to classical music while painting.[4]

Fantastic Realism

An exhibition of Beksiński's works organized by Janusz Bogucki in Warsaw in 1964 was his first major success.[5][6]

Beksiński undertook painting with a passion, working intensely while listening to classical music. He soon became the leading figure in contemporary Polish art. In the late 1960s, Beksiński entered what he himself called his "fantastic period," which lasted into the mid-1980s. This is his best-known period, during which he created disturbing images, showing a gloomy, surrealistic environment with detailed scenes of death, decay, landscapes filled with skeletons, deformed figures, and deserts. These detailed works were painted with his trademark precision. At the time, Beksiński claimed, "I wish to paint in such a manner as if I were photographing dreams."[7]

Despite the grim overtones, Beksiński claimed some of his works were misunderstood; in his opinion, they were rather optimistic or even humorous. For the most part, Beksiński was adamant that even he did not know the meaning of his artworks and was uninterested in possible interpretations; in keeping with this notion, he refused to provide titles for any of his drawings or paintings. Before moving to Warsaw in 1977, he destroyed a selection of his works in his own backyard, without leaving any documentation concerning them.[8]

According to Mexican film director Guillermo del Toro "In the medieval tradition, Beksiński seems to believe art to be a forewarning about the fragility of the flesh––whatever pleasures we know are doomed to perish––thus, his paintings manage to evoke at once the process of decay and the ongoing struggle for life. They hold within them a secret poetry, stained with blood and rust."[9]

Later work

The 1980s marked a transitional period for Beksiński. During this time, his works became more popular in France due to the endeavors of Piotr Dmochowski, and Beksiński achieved significant popularity in Western Europe, the United States, and Japan. His art, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, focused on monumental or sculpture-like images rendered in a restricted and often subdued colour palette, including a series of crosses. Paintings in this style, which often appear to have been sketched densely in coloured lines, were much less lavish than those of his "fantastic period" but just as powerful. In 1994, Beksiński explained, "I'm going in the direction of a greater simplification of the background, and at the same time a considerable degree of deformation in the figures, which are being painted without what's known as naturalistic light and shadow. What I'm after is for it to be obvious at first sight that this is a painting I made".

In the later part of the 1990s, he became interested in computers, the Internet, digital photography and photo manipulation, a medium that he focused on until his death.[10]

Later life and death

Beksiński's wife, Zofia, died in 1998; a year later, on Christmas Eve 1999, his son Tomasz (a popular radio presenter, music journalist and movie translator) committed suicide by drug overdose. Beksiński discovered his son's body.

On 21 February 2005, Beksiński was found dead in his flat in Warsaw with 17 stab wounds on his body; two of the wounds were determined to have been fatal. Robert Kupiec, the teenage son of his longtime caretaker, and a friend were arrested shortly after the crime. On 9 November 2006 Robert Kupiec was sentenced to 25 years in prison, and his accomplice, Łukasz Kupiec, to 5 years by the court of Warsaw. Before his death, Beksiński had refused to loan Robert Kupiec a few hundred złoty (approximately US$100).[11]

Personality

Although Beksiński's art was often grim, he himself was known to be a pleasant person who took enjoyment from conversation and had a keen sense of humor. He was modest and somewhat shy, avoiding public events such as the openings of his own exhibitions. He credited music as his main source of inspiration. He claimed not to be much influenced by literature, cinema or the work of other artists, and almost never visited museums or exhibitions. Beksiński avoided concrete analysis of the content of his work, saying "I don't want to say or convey anything. I just paint what comes to my mind".[12] He was especially dismissive of those who sought or offered simple answers to what his work 'meant'.

He suffered from obsessive–compulsive disorder,[13] which made him reluctant to travel;[14] he referred to his condition as "neurotic diarrhea".[14]

Artistic legacy

The town of Sanok, Poland, houses a museum dedicated to Beksiński. A Beksiński museum housing 50 paintings and 120 drawings from the Dmochowski collection (who owns the biggest private collection of Beksiński's art[15]), opened in 2006 in the City Art Gallery of Częstochowa, Poland. On 18 May 2012 with the participation of Minister of Regional Development Elżbieta Bieńkowska and others took place ceremonial opening of The New Gallery of Zdzisław Beksiński in the rebuilt wing of the castle. On 19 May 2012, The New Gallery opened for the public.[16] A 'Beksiński cross', in the characteristic T-shape frequently employed by the artist, was installed for Burning Man to honour the artist's memory.[13]

Short stories

During the years 1963–1965, Beksiński wrote short stories. However, he was unhappy with the results and sealed them away, deciding to hone his skills in painting instead.[17] For half a century, they remained a secret to everyone except the artist's closest friends and family. In 2015, a decade after Beksiński was killed, a collection of his short stories was published. Despite their unfinished and chaotic nature, the literary works of Beksiński are considered an intriguing journey into his past, reminiscent of his later dreamlike paintings; they vary from abstract onirist tales and philosophical self-reflections to metaphorical post-apocalyptic fiction and crime thriller stories.[18][19] Beksiński's literary period is described as "short and intensive", as he wrote 40 short stories in fewer than two years, experimenting with form and narrative.[20][21]

In other media

Film

- Beksiński's works inspired the surrealist imagery in William Mallone's horror film Parasomnia (2008).[22]

- 2016 saw the release of feature film The Last Family by Jan P. Matuszyński, a biopic focusing on Beksiński's family life. The film was well-received, scoring 86% on Rotten Tomatoes.[23]

- An unnamed painting made by Beksiński served as the main inspiration for the physical appearance of the strange skeleton found inside the cave in the 2020 film The Empty Man.[24]

Literature

- His works are the main theme of Javier Cobo's novel, "Haereditatem", in which a murderer replicates Beksiński's paintings. [25]

Music

- Black metal artist Leviathan used an untitled 1983 painting as the cover of the compilation album Verräter in 2002.

- Ukrainian black metal band Blood of Kingu used an untitled painting from 1977 as the cover of their second album Sun in the House of the Scorpion in 2010.[26][27]

- The unblack metal band Antestor used "The Trumpeter" as cover art for their album Omen (2012).[28] In a 2013 interview, Antestor explained that they chose "The Trumpeter" because "Our music represents the more broken and monster-like feelings of our humanity, like the apparition in this picture."[29]

Video games

- The Medium (2021) modelled its supernatural setting after Beksiński's artwork.[30]

- Returnal (2021)'s world design was partially inspired by Beksiński's work.[31]

- Scorn (2022) draws inspiration from the art of Beksiński and H. R. Giger.[32]

References

- Krzysztof Jurecki (August 2004). "Zdzisław Beksiński". Culture.pl, Museum of Art in Łódź. Translated by Marek Kępa, February 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017.

- Polska Agencja Prasowa (23 February 2005). "Morderstwo malarza Zdzisława Beksińskiego. Zabójca Beksińskiego posiedzi 25 lat – odwołanie oddalone". Super Express (in Polish). Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- "Life and work". muzeum.sanok.pl. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Gerakiti, Errika (11 September 2019). "The Dystopian Surrealism of Zdzislaw Beksinski". Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- "Beksiński nieobojętny. 27 prac, które poruszą każdego" (in Polish). 16 June 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Beksiński w Warszawie!" (in Polish). Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Moje sny czasem spotykają się ze snami Beksińskiego" (in Polish). 8 November 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Artystyczne eksperymenty Zdzisława Beksińskiego" (in Polish). 18 October 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Guillermo del Toro>Quotes". Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "Beksiński od fotografii do wirtualnej rzeczywistości. Ponad sto prac w Koneserze" (in Polish). 14 April 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Painter Zdzislaw Beksinski found stabbed to death". Lincoln Journal Star. The Associated Press. 21 February 2005. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- "Twórczość Zdzisława Beksińskiego" (in Polish). 20 February 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Zdzislaw Beksinski: The Dystopian Surrealist Painter You Should Know". 5 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "About Zdzisław Beksiński - biography, techniques, facts, quotes, photography and more".

- Sny Beksińskiego Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine November 2015.

- "Otwarcie Galerii Beksińskiego w Sanoku w 2012" (in Polish). 7 February 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- Chomiszczak, Tomasz (2016). "Posłowie: „Zaledwie okruchy, bezużyteczne szczątki, niedojedzone przez czas resztki". Prozatorskie do-myślenia Zdzisława Beksińskiego". In Beksiński, Zdzisław (ed.). Opowiadania. Bosz. pp. 356–409. ISBN 978-83-7576-253-2.

- krzysiek66 (29 May 2015). "Zdzisław Beksiński "Opowiadania"". ksiazkizklimatem.wordpress.com. WordPress. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- "Opowiadania – Zdzisław Beksiński". lubimyczytac.pl. Lubimyczytać.pl. 12 July 2021. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- "Opowiadania - Zdzisław Beksiński". empik.com. Empik. 13 July 2021. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- Zdzisław Beksiński. Opowiadania. 13 July 2021. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Parasomnia preview Archived 8 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine on Hollywood Gothique.com

- The Last Family Archived 18 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine on Rotten Tomatoes.com

- Jacob Knight; Marten Carlson (3 April 2021). "Bonus Features #8 - Writer/Director David Prior (The Empty Man)". Secret Handshake Cinema. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- "Haereditatem - Editorial Avant".

- "DmochowskiGallery.net - galeria - Sala 10. Obrazy. Lata 1968-1983". Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Blood Of Kingu - Sun In The House Of The Scorpion". Discogs. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Synn, Andy (15 January 2013). "Antestor: "Omen"". No Clean Singing. Islander. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Beck, Chris (February 2013). "Antestor – Taking Care of Unfinished Business" (PDF). HM (163): 46–49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- Watts, Steve (7 May 2020). "Upcoming Horror Game's Key Feature Impossible Without Xbox Series X, Developer Teases". GameSpot. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "INTERVIEW: We talked to the Returnal developers about Lovecraft, American horror houses and the relationship with Sony". Newsy Today. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- "Scorn game director Ljubomir Peklar talks sexual imagery". Shacknews. 25 May 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

Sources

- Cowan, J. (Ed.) 2006: The Fantastic Art of Beksiński – Zdzislaw Beksiński: 1929–2005, 3rd edn., Galerie Morpheus International, Las Vegas. ISBN 1-883398-38-X.

- Dmochowski, A. & P. 1991: Beksiński – Photographies, Dessins, Sculptures, Peintures, 2nd edn., API Publishing (Republic of Korea).

- Dmochowski, A. & P. 1991: Beksiński – Peintures et Dessins 1987–1991, 1st edn., API Publishing (Republic of Korea).

- Gazeta Wyborcza, an interview with Zdzisław Beksiński

- Kulakowska-Lis, J. (Ed.) 2005: Beksiński 1, 3rd edn.; with introduction by Tomasz Gryglewicz. Bosz Art, Poland. ISBN 83-87730-11-4.

- Kulakowska-Lis, J. (Ed.) 2005: Beksiński 2, 2nd edn.; with introduction by Wieslaw Banach. Bosz Art, Poland. ISBN 83-87730-42-4.

External links

- Beksiński Official Youtube channel with interviews and documentary footage

- Beksiński Official Store

- Zdzisław Beksiński at Culture.pl

- Zdzisław Beksiński virtual museum (in Polish, German, English, and French)

- Zdzisław Beksiński gallery (in Polish)

- An Artist does not live anymore. In memoriam for Zdzisław Beksiński by a film director Piotr Andrejew, KINO, no. 6/2005 (in Polish)

- Documentary crowdfunding Crowdfunder to finance a feature-length documentary on Beksiński's life

- The Cursed Paintings of Zdzisław Beksiński at Culture.pl

- Zdzisław Beksiński's Life and Work from Historical Museum in Sanok where much of his work is housed