Zarzuela

Zarzuela (Spanish pronunciation: [θaɾˈθwela]) is a Spanish lyric-dramatic genre that alternates between spoken and sung scenes, the latter incorporating operatic and popular songs, as well as dance. The etymology of the name is uncertain, but some propose it may derive from the name of a royal hunting lodge, the Palace of Zarzuela, near Madrid, where that type of entertainment was allegedly first presented to the court.[1] The palace in turn was named after the brambles (zarzas) that grew there.

There are two main forms of zarzuela: Baroque zarzuela (c. 1630–1750), the earliest style, and Romantic zarzuela (c. 1850–1950). Romantic zarzuelas can be further divided into two main subgenres, género grande and género chico, although other sub-divisions exist.

Zarzuela spread to the Spanish dominions, and many Spanish-speaking countries – notably Cuba – developed their own traditions. Zarzuela is also a strong tradition in the Philippines, where it is also referred to in certain dialects as sarswela/sarsuela.[2] Other regional and linguistic variants in Spain include the Basque zartzuela and the Catalan sarsuela.

A masque-like musical theatre had existed in Spain since the time of Juan del Encina. The zarzuela genre was innovative in giving a dramatic function to the musical numbers, which were integrated into the plot of the work. Dances and choruses were incorporated as well as solo and ensemble numbers, all to orchestral accompaniment.

Baroque zarzuela

In 1657 at the Royal Palace of El Prado, King Philip IV of Spain, Queen Mariana and their court attended the first performance of a new comedy by Pedro Calderón de la Barca, with music by Juan Hidalgo de Polanco titled El Laurel de Apolo (The Laurels of Apollo). El Laurel de Apolo traditionally symbolises the birth of a new musical genre that had become known as La Zarzuela.

Like Calderón de la Barca's earlier El golfo de las sirenas (The Sirens' Gulf, 1657), El Laurel de Apolo mixed mythological verse drama with operatic solos, popular songs and dances. The characters in these early, baroque zarzuelas were a mixture of gods, mythological creatures and rustic or pastoral comedy characters; Antonio de Literes's popular Acis y Galatea (1708) is yet another example. Unlike some other operatic forms, there were spoken interludes, often in verse.

Italian influence

In 18th-century Bourbon Spain, Italian artistic style dominated in the arts, including Italian opera. Zarzuela, though still written to Spanish texts, changed to accommodate the Italian vogue. During the reign of King Charles III, political problems provoked a series of revolts against his Italian ministers; these were echoed in theatrical presentations. The older style zarzuela fell out of fashion, but popular Spanish tradition continued to manifest itself in shorter works, such as the single-scene tonadilla (or intermezzo) of which the finest literary exponent was Ramón de la Cruz. Musicians such as Antonio Rodríguez de Hita were proficient in the shorter style of works, though he also wrote a full-scale zarzuela with de la Cruz entitled Las segadoras de Vallecas (The Reapers of Vallecas, 1768). José Castel was one of several composers to write for the Teatro del Príncipe.

19th century

In the 1850s and 1860s a group of patriotic writers and composers led by Francisco Barbieri and Joaquín Gaztambide revived the zarzuela form, seeing in it a possible release from French and Italian music hegemony. The elements of the work continue to be the same: sung solos and choruses, spiced with spoken scenes, and comedic songs, ensembles and dances. Costume dramas and regional variations abound, and the librettos (though often based on French originals) are rich in Spanish idioms and popular jargon.

The zarzuelas of the day included in their librettos various regionalisms and popular slang, such as that of Madrid castizos. Often, the success of a work was due to one or more songs that the public came to know and love. Despite some modifications the basic structure of the zarzuela remained the same: dialogue scenes, songs, choruses, and comic scenes generally performed by two actor-singers. The culminating masterpieces from this period were Barbieri's Pan y toros and Gaztambide's El juramento. Another notable composer from this period was Emilio Arrieta.

Romantic zarzuela

After the Glorious Revolution of 1868, the country entered a deep crisis (especially economically), which was reflected in theatre. The public could not afford high-priced theatre tickets for grandiose productions, which led to the rise of the Teatros Variedades ("variety theatres") in Madrid, with cheap tickets for one-act plays (sainetes). This "theatre of an hour" had great success and zarzuela composers took to the new formula with alacrity. Single-act zarzuelas were classified as género chico ("little genre") whilst the longer zarzuelas of three acts, lasting up to four hours, were called género grande ("grand genre"). Zarzuela grande battled on at the Teatro de la Zarzuela de Madrid, founded by Barbieri and his friends in the 1850s. A newer theatre, the Apolo, opened in 1873. At first it attempted to present the género grande, but it soon yielded to the taste and economics of the time, and became the "temple" of the more populist género chico in the late 1870s.

Musical content from this era ranges from full-scale operatic arias (romanzas) through to popular songs, and dialogue from high poetic drama to lowlife comedy characters. There are also many types of zarzuela in between the two named genres, with a variety of musical and dramatic flavours.

Many of the greatest zarzuelas were written in the 1880s and 1890s, but the form continued to adapt to new theatrical stimuli until well into the 20th century. With the onset of the Spanish Civil War, the form rapidly declined, and the last romantic zarzuelas to hold the stage were written in the 1950s.

Whilst Barbieri produced the greatest zarzuela grande in El barberillo de Lavapiés, the classic exponent of the género chico was his pupil Federico Chueca, whose La gran vía (composed with Joaquín Valverde Durán) was a cult success both in Spain and throughout Europe.

The musical heir of Chueca was José Serrano, whose short, one act género chico zarzuelas - notably La canción del olvido, Alma de dios and the much later Los claveles and La dolorosa - form a stylistic bridge to the more musically sophisticated zarzuelas of the 20th century.

While the zarzuela featured (or even glorified) popular customs, festivals, and manners of speech, especially those of Madrid, something never found in a zarzuela is social criticism. They celebrated the established order of society; if a zarzuela advocated for anything, it would be for the slowing or elimination of social change.

20th century

From about 1900, the term género ínfimo ("degraded" or "low genre") was coined to describe an emerging form of entertainment allied to the revista (revue) type of musical comedy: these were musical works similar to the género chico zarzuela but lighter and bolder in their social criticism,[3] with scenes portraying sexual themes and many verbal double entendres. One popular work from the género ínfimo years is La corte de Faraón (1910), by Vicente Lleó, which was based on the French operetta Madame Putiphar.

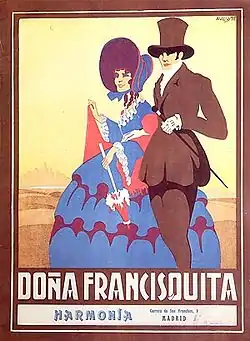

In the second decade of the century, the influences of Viennese operetta and the English followers of Sullivan such as Lionel Monckton[4] made themselves felt, in works such as Molinos de viento and El asombro de Damasco (both by Pablo Luna), before the Spanish tradition of great acts was reasserted in Amadeu Vives's Doña Francisquita (1923). The zarzuela continued to flourish in the 1930s, thanks to composers of the stature of Pablo Sorozábal – who reinvigorated it as a vehicle for socio-political comment – Federico Moreno Torroba, and Francisco Alonso.

However, the Spanish Civil War brought a decline of the genre, and after the Second World War, its extinction as a live genre was almost total. There were no new authors and the compositions are not renovated. There have been no significant new works created since the 1950s; the existing zarzuela repertoire is costly to produce, and many classics have been performed only sporadically in recent years, at least professionally.

The genre has again found favour in Spain and elsewhere: younger people, in particular, have been drawn to its lyrical music and theatrical spectacle in the 1940s and 1950s. Spanish radio and television have dedicated time to zarzuela in 1978, not least in a popular series of programs produced by TVE and entitled Antología de la zarzuela ("Zarzuela Anthology"). These were based on lip syncs of the classic recordings of the 1940s and 1950s. Some years earlier, impresario José Tamayo worked a theatrical show of the same name which popularized pieces of zarzuela through several national and international tours.[5]

Zarzuela in Catalonia

While the zarzuela tradition flourished in Madrid and other Spanish cities, Catalonia developed its own zarzuela, with librettos in Catalan. The atmosphere, the plots, and the music were quite different from the model that triumphed in Madrid, as the Catalan zarzuela was looking to attract a different public, the bourgeois classes. Catalan zarzuela was turned little by little into what is called, in Catalan, teatre líric català ("Catalan lyric theater"), with a personality of its own, and with modernista lyricists and composers such as Enric Granados or Enric Morera.

In the final years of the 19th century, as modernisme emerged, one of the notable modernistas, and one of Felip Pedrell's pupils, Amadeu Vives came onto the Barcelona scene. He contributed to the creation of the Orfeó Català in 1891, along with Lluís Millet. In spite of a success sustained over many years, his musical ambition took him to Madrid, where zarzuela had a higher profile. Vives became one of the most important zarzuela composers, with such masterpieces as Doña Francisquita.

Zarzuela in Cuba and Mexico

In Cuba the afrocubanismo zarzuelas of Ernesto Lecuona (María la O; El cafetal), Eliseo Grenet (La virgen morena) and Gonzalo Roig (Cecilia Valdés, based on Cirilo Villaverde's classic novel) represent a brief golden age of political and cultural importance. These and other works centred on the plight of the mulata woman and other black underclasses in Cuban society. The outstanding star of many of these productions was Rita Montaner.

Mexico likewise had its own zarzuela traditions. One example is Carlo Curti's La cuarta plana, starring Esperanza Iris.[6]

Zarzuela in the Philippines

In the Philippines, the Zarzuela Musical Theatre has been widely adapted by Filipinos in their native cultures, notably in urban areas. The theatre was only introduced by the Spanish in 1878, despite being part of the Spanish Empire since the middle of the 16th century. During this time, the plays were performed only by Spanish people. By 1880, majority of the performers and writers were Filipinos, notably Philippine national hero, José Rizal, who was fond of the play. Afterwards, local languages, instead of Spanish, were used to perform the complex theatre, with additions from multiple cultures throughout the archipelago.

When the Philippines was colonized by the Americans in the early 20th century, the humor from the moro-moro play was added into the Philippine zarzuela, while moving away from the traditional Spanish zarzuela. The theatre afterwards was used by Filipinos to express freedom from discrimination and colonial rule, depicting the Filipino people triumphant against the Spanish and Americans by the end of each play. The revolutionary overtones of the play prompted the American colonialists to arrest various performers and writers of the Philippine zarzuela, to the extent of forcefully shutting down entire zarzuela companies in the Philippines. In the 1920s, due to the introduction of the cinema, the zarzuela became widely popular in the rural areas, disabling the Americans from stopping the plays from spreading. The Philippine zarzuela evolved into a kind of comedy of manners distinct to the Filipino taste. In 2011, the performing art was cited by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts as one of the intangible cultural heritage of the Philippines under the performing arts category that the government may nominate in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. In 2012, through a partnership with UNESCO, the Philippine government established the documents needed for the safeguarding of the Philippine zarzuela. UNESCO has cited the Philippine zarzuela as the national theatre and opera of the Philippines.[7]

Recorded zarzuela

From 1950 onwards, zarzuela prospered in a series of LP recordings from EMI, Hispavox and others, with worldwide distribution. A series produced by the Alhambra company of Madrid, the majority conducted by the leading Spanish conductor Ataulfo Argenta had particular success. Many featured singers soon to become world-famous, such as Teresa Berganza, Alfredo Kraus and Pilar Lorengar; and later, Montserrat Caballé and Plácido Domingo. Less known performers such as Ana María Iriarte, Inés Ribadeneira, Toñy Rosado, Carlos Munguía, Renato Cesari, and others frequently lent their voices to the recordings. The choirs of Orfeón Donostiarra and Singers' Choir of Madrid also contributed, rounding out the overall quality of the works. After Argenta's death others such as Indalecio Cisneros and Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos continued in his footsteps. There were also recordings made conducted by the composers themselves, such as Pablo Sorozábal and Federico Moreno Torroba. Many well-known singers, including Victoria de los Ángeles and Montserrat Caballé, have recorded albums of zarzuela songs and arias.

Many zarzuela productions are now to be seen on DVD and Blu-ray disc. In March 2009, EuroArts released Amor, Vida de Mi Vida, a recording on Blu-ray disc of an August 2007 zarzuela concert by Plácido Domingo and Ana María Martínez, with the Mozarteum Orchestra of Salzburg conducted by Jesús López-Cobos.[8] In April 2009, BBC/Opus Arte released a Blu-ray disc of a July 2006 performance of Federico Moreno Torroba's Luisa Fernanda with Plácido Domingo and Nancy Herrera, recorded at the Teatro Real de Madrid with Jesús López-Cobos conducting.[9]

In the United States, the Jarvis Conservatory of Napa, California, between 1996 and 2005, mounted several full zarzuela productions, subsequently issued on DVD and online. The series includes La dolorosa; La Gran Via; Luisa Fernanda; La verbena de la Paloma; La Rosa del Azafrán; La revoltosa; Agua, Azucarillos y Aguardiente; Doña Francisquita; Gigantes y Cabezudos; La alegría de la huerta; La chulapona; Luis Alonso (Giménez, 1896); and El barberillo de Lavapiés.[10]

Zarzuela composers

Spanish zarzuelas selection (including zarzuela-style operas)

- Adiós a la bohemia (1933) Pablo Sorozábal

- Agua, azucarillos y aguardiente (1898) Federico Chueca

- La alegría de la huerta (1900) Federico Chueca

- Alma de Dios (1907) José Serrano

- El año pasado por agua (1889 ) Federico Chueca

- El asombro de Damasco (1916) Pablo Sorozábal

- El barberillo de Lavapiés (1874) Francisco Asenjo Barbieri

- El bateo (1901) Federico Chueca

- Black, el payaso (1942) Pablo Sorozábal

- La boda de Luis Alonso (1896) Gerónimo Giménez

- Bohemios (1904) Vives

- La bruja (1889) Ruperto Chapí

- Los burladores (1948) Pablo Sorozábal

- La calesera (1925) Francisco Alonso

- La canción del olvido (1928) José Serrano

- El caserío (1926) Jesús Guridi

- El chaleco blanco (1890) Federico Chueca

- La chulapona (1934) Federico Moreno Torroba

- Los claveles (1929) José Serrano

- La corte de Faraón (1910) Vicente Lleó

- Los diamantes de la corona (1854) Francisco Asenjo Barbieri

- La Dogaresa (1916) Rafael Millán

- La dolorosa (1930) José Serrano

- Don Gil de Alcalá (1932) Manuel Penella

- Don Manolito (1943) Pablo Sorozábal

- Doña Francisquita (1923) Amadeo Vives

- El dúo de La africana, (1893) Manuel Fernández Caballero

- La fiesta de San Antón (1898) Tomás Torregrosa

- La fontana del placer José Castel

- Los gavilanes (1923) Jacinto Guerrero

- La generala (1912) Amadeo Vives

- Gigantes y cabezudos (1898) Manuel Fernández Caballero

- Las golondrinas (1914) José María Usandizaga

- La Gran Vía (1886) Federico Chueca

- El huésped del Sevillano (1926) Jacinto Guerrero

- Jugar con fuego (1855) Francisco Asenjo Barbieri

- El juramento (1854) Joaquín Gaztambide

- Katiuska (1931) Pablo Sorozábal

- Las Leandras (1931) Francisco Alonso

- Luisa Fernanda (1932) Federico Moreno Torroba

- La del manojo de rosas (1934) Pablo Sorozábal

- Marina (1855/71) Emilio Arrieta

- Maruxa (1914) Amadeo Vives

- La leyenda del beso (1924) Reveriano Soutullo and Juan Vert

- Me llaman la Presumida (1935) Francisco Alonso

- Molinos de viento (1910) Pablo Luna

- La montería (1923) Jacinto Guerrero

- El niño judío (1918) Pablo Luna

- Pan y toros (1864) Francisco Asenjo Barbieri

- La parranda (1928) Francisco Alonso

- La patria chica (1909) Ruperto Chapí

- La pícara molinera (1928) Pablo Luna

- La revoltosa (1897) Ruperto Chapí

- El rey que rabió (1890) Ruperto Chapí

- La rosa del azafrán (1930) Jacinto Guerrero

- El santo de la Isidra (1898) Tomás Torregrosa

- El señor Joaquín (1900) Manuel Fernández Caballero

- Los sobrinos del capitán Grant (1877) Manuel Fernández Caballero

- La del Soto del Parral (1927) Reveriano Soutullo and Juan Vert

- La tabernera del puerto (1936) Pablo Sorozábal

- La tempestad (1882) Ruperto Chapí

- La tempranica (1900) Gerónimo Giménez

- La verbena de la Paloma (1894) Tomás Bretón

- La viejecita (1897) Manuel Fernández Caballero

- La villana (1927) Amadeo Vives

References

- Corominas, Joan (1980). Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua castellana (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Madrid: Editorial Gredos.

Zarzuela, princ. S. XVII: el nombre de esta representación lírico-dramática viene, según algunos, del Real Sitio de la Zarzuela, donde se representaría la primera, pero la historia del vocablo no se ha averiguado bien y en su primera aparición es nombre de una danza.

- Antonio, Edwin (7 February 2009). "Zarzuela Ilocana in Competition". Treasures of Ilocandia and the World. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- Doppelbauer, Max; Sartingen, Kathrin, eds. (2010). De la zarzuela al cine: Los medios de comunicacion populares y su traduccion de la voz marginal (in Spanish). München: Martin Meidenbauer. ISBN 978-3-89975-208-3.

- Webber, Christopher (2005). "El asombro de Damasco". zarzuela.net (Review). Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2005.

- Torres, Rosana (16 December 1987). "Tamayo presenta en la 'Nueva antología' lo más sobresaliente de la zarzuela moderna". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Clark, Walter Aaron, ed. (2002). From Tejano to Tango: Latin American Popular Music. New York: Routledge. p. 101.

- "Zarzuela – Musical Theatre" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018 – via ichcap.org.

- Erickson, Glenn (1 May 2009). "Amor, Vida de Mi Vida: Zarzuelas by Plácido Domingo and Ana María Martínez (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- Kauffman, Jeffrey (27 June 2009). "Luisa Fernanda (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- "Zarzuela Video Catalogue: Productions From the Jarvis Conservatory". Jarvis Conservatory. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

Further reading

- Alier, Roger (auct.) "Zarzuela", in L. Macy (ed.). New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians Online. Accessed 4 Jul 05. www.grovemusic.com(subscription required) Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Casares Rodicio, Emilio (ed.). Diccionario de la Zarzuela. España e Hispanoamérica. (two vols.) Madrid, ICCMU, 2002-3

- Cincotta, Vincent J. Zarzuela-The Spanish Lyric Theatre. University of Wollongong Press, rev. ed. 2011,pp. 766 ISBN 0-86418-700-9

- History of Zarzuela Archived 29 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine at Zarzuela.net

- Pizà, Antoni. Antoni Literes. Introducció a la seva obra (Palma de Mallorca: Edicions Documenta Balear, 2002) ISBN 84-95694-50-6* Salaün, Serge. El cuplé (1900-1936). (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1990)

- Serna, Pierre-René. Guide de la Zarzuela - La zarzuela de Z à A. Bleu Nuit Éditeur, Paris, November 2012, 336 pp, 16,8 x 24 cm, ISBN 978-2-913575-89-9

- Young, Clinton D. Music Theater and Popular Nationalism in Spain, 1880–1930. Louisiana State University Press, 2016.

- Webber, Christopher. The Zarzuela Companion. Maryland, Scarecrow Press, 2002. Lib. Cong. 2002110168 / ISBN 0-8108-4447-8

External links

- Zarzuela.net edited by Christopher Webber and Ignacio Jassa Haro

- Zarzuela Discography at operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- Zarzueleros.com in Spanish.

- The Fernández-Shaw saga and the lyrical theatre (in English and Spanish)

%252C_Martin_Style_3-17_(1859)_-_C.F._Martin_Guitar_Factory_2012-08-06_-_011.jpg.webp)