Zarafa (giraffe)

Zarafa (January 1824[lower-alpha 1] – 12 January 1845) was a female Nubian giraffe who lived in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris for 18 years. A gift from Muhammad Ali of Egypt to King Charles X of France, she was one of three giraffes Muhammad Ali sent to European rulers in 1827. These were the first giraffes to be seen in Europe for over three centuries, since the Medici giraffe was sent to Lorenzo de' Medici in Florence in 1486. She didn't receive the name "Zarafa" until 1985.[2]

Background

The giraffe known today as Zarafa was one among a series of diplomatic gifts[lower-alpha 2] exchanged between Charles X of France and the Ottoman Viceroy of Egypt, Mehmet Ali Pasha, to enhance their relationship.

Biography

The young Nubian giraffe was captured by Arab hunters near Sennar in Sudan and first taken by camel, then sailed by felucca on the Blue Nile to Khartoum. From there she was transported down the Nile on a specially constructed barge to Alexandria.[3] She was accompanied by three cows that provided her with 25 litres of milk each day.

From Alexandria, she embarked on a ship to Marseilles, with an Arab groom, Hassan, and Drovetti's Sudanese servant, Atir.[4] Because of her height, a hole was cut through the deck above the cargo hold through which she could poke her neck. After a voyage of 32 days, she arrived in Marseilles on 31 October 1826. Fearing the dangers of transporting her by boat to Paris around the Iberian peninsula and up the Atlantic coast of France to the Seine, it was decided that she should walk the 900 km to Paris.

_by_Jacques_Raymond_Brascassat.jpg.webp)

She over-wintered in Marseilles, where she was joined by the naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire for the walk. He ordered a two-part yellow coat to keep her warm, and shoes for her feet. She set out on 20 May 1827,[4] already 15 cm taller than when she arrived in Marseilles. She was accompanied by her cows and Saint-Hilaire, then aged 55, who walked with her. The trip to Paris took 41 days. She was a spectacle in each town she passed through, Aix-en-Provence, Avignon, Orange, Montelimar and Vienne. She arrived in Lyon on 6 June, where she was greeted by an enthusiastic crowd of 30,000.

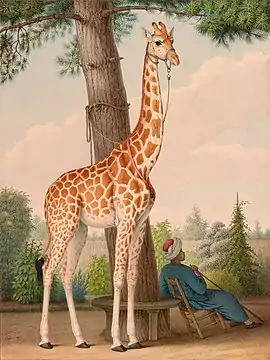

She was presented to the King at the chateau of Saint-Cloud in Paris on 9 July 1827, and took up residence in the Jardin des Plantes. Now standing nearly 4 m high, Zarafa's arrival in Paris caused a sensation. Over 100,000 people came to see her, approximately an eighth of the population of Paris at the time. Honoré de Balzac wrote a story about her; Gustave Flaubert (then a young child) travelled from Rouen to see her. La mode à la girafe swept the nation; hair was arranged in towering styles, spotted fabrics were all the rage. The Journal des Dames reported that the color known as "belly of giraffe" became extremely popular.[5] Porcelain and other ceramics were painted with giraffe images. She was painted by Nicolas Huet,[5] Jacques Raymond Brascassat and many others.

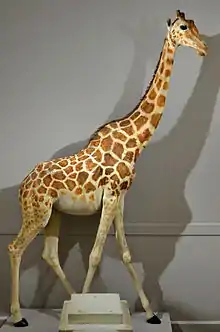

Zarafa remained in Paris for a further 18 years until her death, attended to the end by Atir. Her corpse was stuffed and displayed in the foyer of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris for many years, before being moved to the Museum of Natural History of La Rochelle, where it remains.

Names

According to Saint-Hilaire, she was called le bel animal du roi ("The Beautiful Animal of the King") during her trip from Marseille to Paris[6] and she was dubbed la Belle Africaine ("the Beautiful African") by contemporary press. La Gazette referred to her as "her Highness" (pun intended).[lower-alpha 3]

The name "Zarafa" was given to her by American author Michael Allin in his 1998 book Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story, from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris. Zarafa, meaning "charming" or "lovely one" in Arabic, is a phonetic variant of the Arabic word for giraffe: zerafa.[8][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] Olivier Lebleu, author of the new preface to the second edition (2007) of the French journalist Gabriel Dardaud's book Une giraffe pour le roi (the first modern full-length work about France's first giraffe) has taken up the name "Zarafa," as have several other recent authors, including Lebleu himself in his 2006 book Les Avatars de Zarafa. In addition, the eponymous 2012 French animation film, Zarafa uses the name; and even the museum in La Rochelle, where her mounted remains still greet visitors, now refers to her by the name Zarafa.[11]

Other giraffe gifts by Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali Pasha also sent two other giraffes as gifts in 1827, one to George IV of the United Kingdom in London and the other to Francis I of Austria in Vienna. Like the giraffe sent to France, both inspired giraffe crazes in their respective cities. The Austrian giraffe joined the Emperor's menagerie at Schönbrunn Palace but survived for less than one year. Nevertheless, it lived on in the form of Giraffeln pastries, served until the beginning of the First World War, and Giraffentorten (giraffe cakes) which still can be found.[12][13] The English giraffe (or "cameleopard", echoing the terminology used by Pliny) joined the embryonic London Zoo in Regent's Park. It was painted as The Nubian Giraffe in 1827 by Jacques-Laurent Agasse, in an image that includes Edward Cross and, in the background, the giraffe's milk cows from Egypt. The English giraffe survived for less than two years, and was stuffed by John Gould.

In culture

- Zarafa, a 2012 French-Belgian animation film

- Puppet re-enactment:

- From 15th April to 24th June 2023, British artist Sebastian Mayer re-enacted Zarafa's journey through France [14] by walking from Marseille to Paris with a full scale giraffe puppet. The puppet, standing 3m40 tall and weighing 9kg,[15] was fitted with a removable cardboard skin, enabling Mayer to stop in populous places and offer free workshops [16] to local community members, who decorated each skin for the next section of the journey.

References

- Notes

- « On a varié sur son âge compté en nombre de lunes; cependant on est parvenu à concilier quelques renseignemens contradictoires et à établir qu'elle avait pris vingt-deux mois en novembre 1826 » (Various accounts on her age, expressed in lunar months, have been given; however we managed to conciliate contradictory information and to establish that she was 22 months old in November 1826), Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire[1]

- Including an obelisk, later exchanged with the Luxor Obelisk

- "Her Highness was to be presented to his Majesty! how little the king must have looked by a lady 14 feet high! What the ceremonial was I cannot say, but I really believe her Highness was guilty of lèse-majesté — the treason of looking down upon a king, the monarch of the great nation; but her Highness is unbendable by nature, and she has a quality very rare and estimable in the female sex, as all married men will allow; she is mute."[7]

- See also Heather J. Sharkey "La Belle Africaine: The Sudanese Giraffe Who Went to France"[9] Sharkey misreads Dardaud, who did not use the name "Zarafa" in his 1985 text.

- Another Arabic homophonous word, means "charming" or "lovely one" was referenced by Allin as relating to the name, but it was later noted that both words are spelled with different Arabic letters.[10]

- Sources

- « Quelques considérations sur la Girafe », in Audouin, Brongniard et Dumas (dir.), « Annales des sciences naturelles », tome 11, Paris, Crochard, 1827, p.211

- McCouat, Philip. "The art of giraffe diplomacy". Journal of ART in SOCIETY. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- McCouat, Philip. "The art of giraffe diplomacy". Journal of Art in Society.

- Allin, Michael (March 31, 2006). "Book Excerpt: 'Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story'". NPR.org. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Werlin, Katy. "The Fashion Historian: La Mode à la Girafe". The Fashion Historian. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, « Quelques considérations sur la Girafe », in Audouin, Brongniard et Dumas (dir.), « Annales des sciences naturelles », tome 11, Paris, Crochard, 1827, p.213

- Walton, Geri (21 October 2016). "Belle Africaine: The First Giraffe In France - Geri Walton". Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Michael Allin, Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story, from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris, Walker and Company, 1998, 215 p. (ISBN 0-8027-1339-4), p. 5.

- Sharkey, Heather J. (2 January 2015). "La Belle Africaine: The Sudanese Giraffe who went to France". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 49: 39–65. doi:10.1080/00083968.2015.1043712. S2CID 142668677.

- Denys Johnson-Davies (13–19 May 1999). "Journey of a giraffe". Al-Ahram Weekly No.429. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012.

- See the museum's website, http://www.museum-larochelle.fr/visites/parcours.html Archived 2015-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Lebleu, Olivier (11 January 2016). "Long-necked diplomacy: the tale of the third giraffe". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Giraffe Cake". winterthur-tourismus.ch (in German). Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "La France buissonnière : la marche lente de l'homme-girafe". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2023-06-25. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- "Tout en rose, 3,40 m de hauteur : un homme-girafe fait étape à Valence !". ici, par France Bleu et France 3 (in French). 2023-05-11. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- "INSOLITE. 1000 kilomètres avec une girafe sur le dos, le délirant périple d'un Anglais à travers la France". France 3 Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (in French). 2023-05-20. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

Further reading

- Allin, Michael (1998). Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story, from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris. Walker and Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1339-1.

- Milton, Nancy (2013) [1992]. The Giraffe that Walked to Paris. Purple House Press. ISBN 978-1-930900-67-7. Illustrated by Roger Roth

- Passarello, Elena (20 December 2016). "Beautiful Animal of the King". The Paris Review.

- Sharkey, Heather J. "La Belle Africaine : The Sudanese Giraffe Who Went to France" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

External links

- King George IV's giraffe: "The King's Giraffe". John Gould Inc. Australian Museum. 23 August 2006. Archived from the original on 23 August 2006.

- Erik Ringmar. "Audience for a Giraffe: European Expansionism and the Quest for the Exotic" (PDF). Journal of World History, 17:4, December, 2006. pp. 353-97.

- Home by a neck; a giraffe's epic journey from Cairo to Paris - 1825 gift from Muhammad Ali Pasha to Charles X of France, UNESCO Courier, March 1986

- The Nubian Giraffe by Jacques-Laurent Agasse, Royal Trust Collection

- Book Excerpt: 'Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story' from NPR, 31 March 2006

- Nicholls, Henry (20 January 2014). "Meet Zarafa, the giraffe that inspired a crazy hairdo". The Guardian.

- "Zarafa (Giraffe), 1824?-1845". LC Linked Data Service: Authorities and Vocabularies. Library of Congress.