Yoruba culture

Distinctive cultural norms prevail in Yorubaland and among the Yoruba people.[1]

Religion (Ẹsìn)

The Yoruba are said to be religious people, but they are also pragmatic and tolerant about their religious differences. Whilst many profess the Yoruba school of thought; many more profess other faiths e.g. Christianity (Ẹsìn Ìgbàgbọ́), Islam (Ẹsìn Ìmàle) etc.[2]

Law

Yoruba law is the legal system of Yorubaland. It is quite intricate, each group and subgroup having a system that varies, but in general, government begins within the immediate family. The next level is the clan, or extended family, with its own head known as a Baálé. This chief will be subject to town chiefs, and these chiefs are usually themselves subject to their Oba, who may or may not be subject to another Oba himself.[3]

Most of what survived of this legal code has been assimilated into the customary laws of the sovereign nations that the Yoruba inhabit.

Language (Èdè)

Yoruba people traditionally speak the Yorùbá language, a member of the Niger–Congo language family. Apart from referring to the aggregate of dialects and their speakers, the term Yoruba is also used for the standard, written form of the language.[4]

Linguistics

Yoruba written literature begins with the formation of its grammar published in 1843. The standard language incorporates several features from other dialects.[5]

Philosophy

Yoruba culture consists of the folk/cultural philosophy, the autochthonous religion and folktales. They are embodied in Ifa-Ife Divination, known as the tripartite Book of Enlightenment or the Body of Knowledge in Yorubaland and in its diaspora. Other components of the Book of Knowledge or the Book of Enlightenment are psychology, sociology, mathematics, cosmogony, cosmology, and other areas of human interests.

Yoruba cultural thought is a witness of two epochs. The first epoch is an epoch-making history in mythology and cosmology. This is also an epoch-making history in the oral culture during which time the divine philosopher Orunmila was the head and a pre-eminent diviner. He pondered the visible and invisible worlds, reminiscing about cosmogony, cosmology, and the mythological creatures in the visible and invisible worlds. This philosopher, Orunmila, epitomizes wisdom and idealism. He has been said to be more of a psychologist than a philosopher. He is the cultivator of ambitions and desires, and the interpreter of ori (head) and its destiny. The non-literate world, compelled by the need to survive, impelled by the need to unravel the mysteries of the days and nights, made Orunmila to cultivate the idea of Divination.

The second epoch is the epoch of metaphysical discourse. This commenced in the 19th century when the land became a literate land through the diligence and pragmatism of Dr. Ajayi Crowther, the first African Anglican Bishop. He is regarded as the cultivator of modern Yoruba idealism.

The uniqueness of Yoruba thought is that it is mainly narrative in form, explicating and pointing to the knowledge of the causes and nature of things, affecting the corporeal and the spiritual universe and its wellness. Yoruba people have hundreds of aphorisms, folktales, and lores, and they believe that any lore that widens people's horizons and presents food for thought is the beginning of a philosophy.

As it was in the ancient times, Yoruba people always attach philosophical and religious connotations to whatever they produced or created. Hence some of them are referred to as artist-philosophers. This is an accretion to the fact that one can find a sculptor, a weaver, a carver or a potter in every household in Yoruba land.

Despite the fact that the Yoruba cannot detail all their long pedigrees, such as Oduduwa, Obatala, Orunmila, Sango, Ogun, Osun (one of the three wives of Sango), Olokun, Oya (one of the three wives of Sango), Esu, Ososi, Yemoja, Sopona etc., nonetheless it is a fact of truth that they had all impacted the Yoruba people and contributed to the wellness and well-being of the Yoruba society. Without their various contributions, Yoruba land could have been lost in a hay of confusion.

Although religion is often first in Yoruba culture, nonetheless, it is the thought of man that actually leads spiritual consciousness (ori) to the creation and the practice of religion. Thus thought/philosophy is antecedent to religion.

Today, the academic and the nonacademic communities are becoming more and more interested in Yoruba culture, as well as in its Book of Enlightenment. Thus more and more research is being carried out on Yoruba cultural thought, as more and more books are being written on it — embossing its mark and advancing its research amongst non-African thinkers such as the political philosophers and political scientists who are beginning to open their doors to other cultures, widening their views.

Yoruba idealism

Idealism in Yoruba-land and for the Yoruba people is equated with the ideal purpose of life, the search for the meaning of life and the yearning for the best in life. Orunmila, the cultivator of Ifa-Ife divination, is the father of ancient Yoruba idealism. His (divine) idealism has inspired the entire Yoruba people in Africa and in the diaspora, especially those who were stolen (to the Americas and the West Indies) during the inhuman slave trade.

Based on the definition of the Yoruba idealism, which is the search for the meaning of life and the yearning for the best in life, Yoruba idealism is a kind of Enlightenment Movement in its own right, as every scion in the land endeavors to reach the height or the acme of his idealistic ambition.

Orunmila's idealism ushered in a more modern idealism that inspired the pragmatic Dr. Ajayi Crowther in the 19th century, and Chief Obafemi Awolowo in the 20th century, who succeeded in creating a moral atmosphere for the Yoruba land to thrive, impacting a moral majority to which idealism belongs and from which realism emerges. His leadership philosophy helped him with big ideas. He built the first Radio and TV Houses in Africa. He cultivated the big ideas that led to the building of the first modern stadium in Africa and the first Cocoa House in the world. Generally speaking, Yoruba people are idealists by nature.

Art

Sculpture

The Yoruba are said to be prolific sculptors,[6] famous for their terra cotta works throughout the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries; artists have also shown the capacity to make artwork out of bronze.[7]

Esiẹ Museum is a museum in Esiẹ;[8] a neighbouring town to Oro in Irepodun, Kwara. The museum was the first to be established in Nigeria when it opened in 1945. It once housed over a thousand tombstone figures or images representing human beings. It is reputed to have the largest collection of soapstone images in the world.[9] In modern times, the Esie museum has been the center of religious activities and host a festival in the month of April every year.[10]

Textile

Weaving is done on different types of looms in order to create hundreds of different patterns. Adire and Aso Oke are some of the popular textiles in Yoruba land. Adire(tie and dye) is the name given to indigo dyed cloth produced by Yoruba women of south western Nigeria using a variety of resist dye techniques. Adire translates as tie and dye, and the earliest cloths were probably simple tied designs on locally-woven hand-spun cotton cloth much like those still produced in Mali.

Cuisine

_served_in_Birmingham_UK.JPG.webp)

Some common foods native to the Yoruba include moin-moin (steamed bean pudding) and akara (bean cake). Native Yoruba soups include ewedu (jute), gbegiri (which is made from beans), and efo riro (a type of vegetable soup). Such soups as okra soup (locally known as obé ila) and egusi (melon soup) have become very popular in Western Nigeria in recent times and, in addition to Amala (yam flour), a traditional Yoruba meal made of yam flour, these can be eaten with ewedu and gbegiri. Numerous Nigerian meals, including pounded yam (locally referred to as iyan); lafun, a Nigeria fufu made from cassava; semolina; and garri (eba).

Some dishes are prepared specially for festivities and ceremonies. Jollof rice, fried rice and Ofada rice are very common in Nigeria (especially in the southwest region, which includes Lagos). Other popular dishes include Asaro, Efokore, Ekuru and Aro, stews, corn, cassava, and flours (such as maize, yam and plantain flours), eggs, chicken, and assorted meat and fish). Some less well known meals and many miscellaneous staples are arrowroot gruel, sweetmeats, fritters and coconut concoctions; and some breads such as yeast bread, rock buns, and palm wine bread. Yoruba cuisine is quite vast and often includes plantains which can be boiled, fried and roasted.[11]

Music

Music and dance have always been an important part of the Yoruba culture; they are used in many different forms of entertainment. Musical instruments include bata, saworo, sekere, gangan etc. Musical varieties include Juju, Fuji and Afrobeat, with artists including King Sunny Ade, Ebenezer Obey, and KWAM 1.[12]

Naming customs

The Yoruba people believe that people live out the meanings of their names. As such, Yoruba people put considerable effort into naming a baby. Their philosophy of naming is conveyed in a common adage, ile ni a n wo, ki a to so omo l'oruko ("one pays attention to the family before naming a child"): one must consider the tradition and history of a child's relatives when choosing a name.

Some families have long-standing traditions for naming their children. Such customs are often derived from their profession or religion. For example, a family of hunters could name their baby Ogunbunmi (Ogun favors me with this) to show their respect to the divinity who gives them metal tools for hunting. Meanwhile, a family that venerates Ifá may name their child Falola (Ifa has honor).[1]

Naming

Since it is generally believed that names are like spirits which would like to live out their meanings, parents do a thorough search before giving names to their babies. Naming ceremonies are performed with the same meticulous care, generally by the oldest family member. Symbolic of the hopes, expectations and prayers of the parents for the new baby, honey, kola, bitter kola, atare (alligator pepper), water, palm oil, sugar, sugar cane, salt, and liquor each have a place and a special meaning in the world-view of the Yoruba. For instance, honey represents sweetness, and the prayer of the parents is that their baby's life will be as sweet as honey.[13]

After the ritual, the child is named and members of the extended family have the honour of also giving a name to the child. The gift of a name comes with gifts of money and clothing. In many cases, the relative will subsequently call the child by the name they give to him or her, so a new baby may thereafter have more than a dozen names.[14]

Preordained name

- Amutorunwa (brought from heaven)

- Oruko - name

Some Yorubas believe that a baby may come with pre-destined names. For instance, twins (ibeji) are believed to have natural-birth names. Thus the first to be born of the two is called Taiwo or Taiye, shortened forms of Taiyewo, meaning the taster of the world. This is to identify the first twin as the one sent by the other one to first go and taste the world. If he/she stays there, it follows that it is not bad, and that would send a signal to the other one to start coming. Hence the second to arrive is named Kehinde (late arrival); it is now common for many Kehindes to be called by the familiar diminutive "Kenny". Irrespective of the sex the child born to the same woman after the twins is called Idowu, and the one after this is called Alaba, then the next child is called Idogbe. Ige is a child born with the legs coming out first instead of the head; and Ojo (male) or Aina (female) is the one born with the umbilical cord around his or her neck. When a child is conceived with no prior menstruation, he or she is named Ilori. Dada is the child born with locked hair; and Ajayi (nicknamed Ogidi Olu) is the one born face-downwards.[15]

Other natural names include Abiodun (one born on a festival day or period), Abiona (one born on a journey) Abidemi or Bidemi (one born without the presence of its father) i.e the child's father didn't witness his baby's naming ceremony but not dead, maybe he just traveled, Enitan (one of a story) this child might have had any of its parents dead before its birth, Bosede (one born on a holy day); Babatunde/Babatunji (meaning father has come back) is the son born to a family where a father has recently passed. This testifies to the belief in reincarnation. Iyabode, Yeside, Yewande, and Yetunde, ("mother has come back") are female counterparts, names with the same meaning.

Name given at birth

- Oruko - name

- Abi - birthed

- So - named

These are names that are not natural with the child at birth but are given on either the seventh day of birth (for females) and ninth day of birth (for males). Some Yoruba groups practice ifalomo (6th) holding the naming rites on the sixth day. The influence of Christianity and Islam in Yoruba culture was responsible for the eighth-day naming ceremony. Twin-births when they are male and female are usually named on the eighth day but on the seventh or ninth day if they are same-sex twins. They are given in accordance with significant events at time of birth or with reference to the family tradition as has been mentioned above.

Examples of names given with reference to the family tradition include Ogundiran (Ogun has become a living tradition in the family); Ayanlowo (Ayan drumming tradition is honorable); Oyetoso (Chieftaincy is ornament); Olanrewaju (Honor is advancing forward); Olusegun (God has conquered the enemy).

Abiku names

- Abi - birthed, or Bi - born

- Iku - death, or Ku - die / dead

The Yoruba believe that some children are born to die. This is derived from the phenomenon of the tragic incidents of high rate of infant mortality sometimes afflicting the same family for a long time. When this occurs, the family devises various methods to forestall a recurrence, including giving special names at a new birth.[16] Such names reflect the frustration of the poor parents:

- Malomo (do not go again)[17]

- Kosoko (there is no hoe anymore). This refers to the hoe that is used to dig the grave.[18]

- Kashimawo (let's wait and see). This suggests a somewhat cynical attitude in the parent(s).[19]

- Banjoko (sit with me)[20]

- Orukotan (all names have been exhausted)[21]

- Yemiitan (stop deceiving me)[22]

- Kokumo (this will not die)[23]

- Durojaiye (stay and enjoy life)[24]

- Durotimi or Rotimi (stay with me)[25]

- Durosola (stay and enjoy wealth)

Pet names

The Yoruba also have pet names or oriki. These are praise names, and they are used to suggest what the child's family background is or to express one's hope for the child: Akanbi- (one who is deliberately born); Ayinde (one who is praised on arrival); Akande (one who comes or arrives in full determination); Atanda (one who is deliberately created after thorough search). For females, Aduke (one who everyone likes to take care of), Ayoke (one who people are happy to care for), Arike (one who is cared for on sight), Atinuke or Abike (one that is born to be pampered).

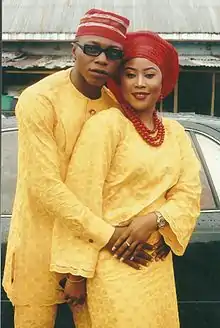

Wedding

The Yoruba culture provides for the upbringing of the child by the extended family. In traditional society, the child is placed with a master of whatever craft the gods specify for him or her (although this rarely happens nowadays). Alternatively, he may take to the profession of the father, in the case of a boy, or the mother, in the case of a girl. The parents have the responsibility for his/her socialization into the norms of the larger society, in addition to giving him a means of livelihood. His or her wedding is also the responsibility of the parents.

The wedding ceremony is the climax of a process that starts with courtship. The young man identifies a young woman that he loves. He and his friends seek her out through various means. The young man sends messages of interest to the young woman until such a time that they are close enough to avoid a go-between (known as an alarina). Then once they both express mutual love, they let their parents know about their feelings for each other. The man's parents arrange to pay a visit to the prospective bride's parents. Once their consent is secured, the wedding day may be set. Prior to the wedding day, the payment of bride price is arranged. This secures the final consent of the bride's parents, and the wedding day is fixed. Once the day has been fixed through either consultation of the Orishas by a babalawo (in the case of followers of the Yoruba religion) or the decision of a man of God (in the case of the Muslims or Christians), the bride and bridegroom are warned to avoid travelling out of town, including to the farm. This is to prevent any mishap. The wedding day is a day of celebration, eating, drinking and dancing for parents, relations, the new husband and wife and their friends and, often, even foes. Marriage is not considered to be only a union of the husband and wife, it is also seen among the Yoruba as the union of the families on both sides. But before the bride goes to her husband's house, she is escorted by different people i.e. family and friends to the door step of her new home in a ritual called Ekun Iyawo meaning 'The cry of the new bride', this is to show that she is sad leaving her parents' home and signify her presence in the new home. There she is prayed for and her legs are washed. It is believed that she is washing every bad-luck that she might have brought into her husband's house away. Before she is finally ushered into her house, if she is an adherent of the Yoruba faith, she is given a calabash (igba) and is then asked to break it. When it breaks, the number of pieces it is broken into is believed to be the number of children she will give birth to. On the wedding night, she and her husband have their first meeting and he is ordinarily expected to find her to be a virgin. If he doesn't, she and her parents are disgraced and may be banished from the village where they live.

While this is the only marital ceremony that is practiced by the more traditional members of the tribe, Muslim and Christian members generally blend it with a nikkah and registry wedding (in the case of Muslims) or a church wedding and registry wedding (in the case of Christians). In their communities, the Yoruba ceremony described above is commonly seen as more of an engagement party than a proper wedding rite.

Money Spraying (Owó-Níná)

Originating from Yorubaland, the Yoruba have always been a very flamboyant people as seen in their art, language, and poetry.[26] Money spraying is an integral part of the Yoruba culture in Southwest Nigeria. It is a tradition loved by many Nigerians today, irrespective of their ethnic background or tribe. Money spraying symbolizes a showering of happiness, good fortune, and a display of the guest's affection for the couple at a wedding ceremony. The bride and groom are ushered in and dance behind the wedding party. Guests walk in in turns or more recently encircle the couple on the dance floor and come forward, placing bills on the couple's forehead, allowing them to “rain down.” As the money is sprayed, 'collectors’ take the cash from the floor and place it in bags for the couple.”

In the mid 40s, the culture was absorbed by other ethnic groups and tribes who had moved into the Yoruba region of Nigeria. Money is now sprayed at weddings, house warmings, thanksgiving, etc across Yorubaland as a good gesture for the celebrants by the attendees. The money is placed one after the other on the celebrant's temple, and is then left to drop onto the floor or into a tray that would later be collected by the celebrants' family or friends.

Funeral (Ìsínku)

In Yoruba belief, death is not the end of life; rather, it is a transition from one form of existence to another. The ogberis (ignorant folks) fear death because it marks the end of an existence that is known and the beginning of one that is unknown. Immortality is the dream of many, as "Eji-ogbe" puts it: Mo dogbogbo orose; Ng ko ku mo; Mo digba oke; Mo duro Gbonin. (I have become an aged ose tree; I will no longer die; I have become two hundred hills rolled into one; I am immovable.) Reference to hills is found in the saying "Gboningbonin ni t'oke, oke Gboningbonin".

The Yoruba also pray for many blessings, but the most important three are wealth, children and immortality: ire owo; ire omo; ire aiku pari iwa. There is a belief in an afterlife that is a continuation of this life, only in a different setting, and the abode of the dead is usually placed at a place just outside this abode, and is sometimes thought of as separated by a stream. Participation in this afterlife is conditional on the nature of one's life and the nature of one's death. This is the meaning of life: to deliver the message of Olodumare, the Supreme Creator by promoting the good of existence. For it is the wish of the Deity that human beings should promote the good as much as is possible. Hence it is insisted that one has a good capacity for moral uprightness and personhood. Personhood is an achieved state judged by the standard of goodness to self, to the community and to the ancestors. As people say: Keni huwa gbedegbede; keni lee ku pelepele; K'omo eni lee n'owo gbogboro L'eni sin. (Let one conduct one's life gently; that one may die a good death; that one's children may stretch their hands over one's body in burial.)

The achievement of a good death is an occasion for celebration of the life of the deceased. This falls into several categories. First, children and grand children would celebrate the life of their parent who passed and left a good name for them. Second, the Yoruba are realistic and pragmatic about their attitude to death. They know that one may die at a young age. The important thing is a good life and a good name. As the saying goes: Ki a ku l'omode, ki a fi esin se irele eni; o san ju ki a dagba ki a ma ni adie irana. (if we die young, and a horse is killed in celebration of one's life; it is better than dying old without people killing even a chicken in celebration.)

It is also believed that ancestors have enormous power to watch over their descendants. Therefore, people make an effort to remember their ancestors on a regular basis. This is ancestor veneration, which some have wrongly labelled ancestor worship. It is believed that the love that exists between a parent and a child here on earth should continue even after death. And since the parent has only ascended to another plane of existence, it should be possible for the link to remain strong.

Gender and Sexuality in Yoruba Culture

Conceptions of Gender in Traditional Yoruba Faith

One can glean an understanding of Yoruba conceptions of gender and sexuality through an examination of how these subjects featured in their faiths and culture. An important insight into the pre-colonial view of women can be gained through a review of the central figures of Yoruba myth.

In one of the myths of the creation of the world, Olodumare, the supreme creator of the Universe created the orishas, divine deities who embodied specific natural forces, human practices, and other important features of the social and natural world. In this story, the orisha Osun, the shining goddess of beauty, fertility, and sensuality, was the youngest of the orishas sent down by the supreme god to set up the world and foster humanity.[27] However, the rest of the Orisha disregarded her contribution, and she was ostracized by them as they used their manly forces to put the world together without her help.[27]

However, their marginalization of Osun coincided with the continual failure of the Earth that was spearheaded by the male orishas, and following their appeal to Olodumare for help, it was revealed that the failure of the world was a result of the men marginalizing Osun and attempting to create a world without the essential feminine influence of Osun.[27] Thus, this story has as a moral the importance of femininity to the orderly working of society in the Yoruba.

Another important figure in the conception of gender and sexuality is Yemoja. According to the different traditions, Yemoja was worshipped as the mother of all Orishas and life on Earth, or the patron deity of women and mothers, as well as of the Ogun river and other in Nigeria.[28] In all cases, she is worshipped as a river goddess to whom adherents of the Ifa religion direct their appeals for fertility.[28] She is one of the most popular deities, and is known by multiple names, including La Sirene, and Yemaya by adherents in Cuba and other parts of the Caribbean.[28]

Shango was, according to tradition, a ruler of the powerful Yoruba polity of Oyo. As is typical of stories in the Yoruba oral tradition, there are multiple variations of the story of Shango. Nevertheless, the essence of the myth maintains that in his mortal life, King Shango ruled the kingdom of Oyo during a period of great battles and conquest.[29] But his rule ended prematurely following his suicide, in some versions due to being overthrown by subordinate chief, in some versions due to his grief after accidentally killing his family with a newly discovered spell. In any case, his great achievements were posthumously by the gods, and following his death the Orisha deified him, whereupon he became Shango, the Yoruba Orisha of lightning.[29] He is recognized in Africa, Cuba, and elsewhere as a god of thunder and power, symbolizing masculinity and virility.

Another deity which encompasses the Yoruba view of masculinity is Ogun, the Orisha whose cult worships him as the patron deity of iron, war, and hunting.[30] According to the oral tradition, when the Orishas were sent by the Supreme Creator to put the newly created world in order, they were faced with a massive, unfathomable forest which blocked their sight and their access. The Orishas' effort to cut down this forest was futile, as the tools they had were of wood. Ogun then retreated to the inside of a mountain and, after gathering the necessary materials, created iron, from which he was able to fashion suitable tools and clear away the indomitable forest.[31] As the patron god of iron and war, Ogun is the Orisha to whom men and blacksmiths appeal to for matters relating to war and the creation of weapons and tool; thus he encapsulates much of the masculine themes which are relevant to the life of a strong, manly Yoruba warrior, hunter or craftsman.[30] Like Shango, Osun and Yemoja, he is still widely revered among the descendants of the Yoruba in Nigeria and the Caribbean.

These are only four of hundreds of different venerated by the different Yoruba polities in Yorubaland. The Yoruba as a people have never been politically or culturally heterogeneous, and people's views of the orisha varied by according to the dominant views and practices. That being said, Osun, Yemoja, Shango, and Ogun are four of the most widely worshipped deities in the Yoruba pantheon, as demonstrated by the abundance of worshippers of these specific deities in regions outside of Africa. Thus, the cultural significance of these deities provides useful insight into Yoruba conceptions of gender, based on the deities they used to conceptualize these ideas in their theology.

Gender Roles

Yorùbá language does not include distinct gender-based pronouns, therefore, Yoruba culture is not as linguistically dichotomized in regards to gender as many Western societies are. Rather, the existence of gender distinctions pertaining to societal roles and expectations can be attributed to mythology, with female and male principles represented differently. These representations typically adhere to the following principles along gendered lines; femininity and coolness, masculinity and toughness.[32] These ideals thus inform gendered norms in Yoruba society. These norms however do not include norms of oppression between genders as the overarching philosophy is one of complimentary gender relations. No sex is inherently dominant, rather each gender enjoys prominence in certain areas.[33] Examples would be farming for men and working the marketplace for women.

Polygamy

Polygamy has a longstanding history within traditional Yoruba culture. As seen in a Yoruba framework, marriage is first and foremost a union between families with the goal of childbearing rather than a romantic contract between two individuals.[34] Thus, sexual pleasure and love between the parties involved are not the objects of marriage. Naturally, the position of king holds great importance in Yoruba culture, but importance is also particularly accorded to the king's partners. As it is ideal for the king to produce as many children as possible, he is expected to have more wives than anyone else.[35]

Gender Fluidity

Women as Bridegrooms

As the practice of having multiple wives was common in pre-colonial and colonial times, the primary wife would sometimes encourage and even help her husband find a new wife. This was financially beneficial for the new bride and allowed for the social responsibilities of a wife to be shared between more than one woman.[36]

Actions and Language Not Indicative of Sexual Behaviours

[36] While a senior wife might address the new wife as iyawo mi or aya mi which means my wife, there is no evidence of this being linked to eroticism or a sexual relationship between them. Similarly, in the traditional role of priest, gender fluidity is common but not indicative of homosexuality. The Elegun Sango who are feminine in nature often have many wives and children. The Aboke ‘Badan maintain feminine hairstyles and occasionally dress as women for cultural rites and in the presence of other priests or chiefs. There is no evidence to indicate that the men in either role partake in homosexuality.

Sexual Health

Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention

Among the Yoruba people in Southwestern Africa sexual health is the focus of young people, the elderly are often removed from the conversation. The sexual health of elderly people is not given as much attention as that of young people. They are often excluded from sexual healthcare services and culturally have more faith in traditional forms of prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections than they do in western medicine or condoms. Some acceptable prevention tools are sarun domi and aseje, both of which are traditionally made concoction meant to turn disease into water for the body. Other forms of prevention include incisions, amulets, and wraps.[37]

Condoms in Culture

Among subjects of a research study on the sexual health of Yoruba elders, it was found that 71% of participants were Muslim, most were in polygynous relationship, had no formal education, and were retired. Although some of the subjects did have a formal education, only 20.4% of men and 2.8% of women believed in the usefulness of condoms in the prevention of STIs, making the use of condoms limited and female condoms non-existent.[38] The stigma, shame, lack of awareness of its efficacy, and the misconception about its reduction of sexual pleasure all contribute to the decision not to use them during sex.

Among the elderly Yoruba people, it is commonly accepted than most people will contract gonorrhoea in their lives, one subject of a study even suggesting that only those who have the disease can give birth. Three types of gonorrhoea are acknowledged: those that cause people to ooze pus, blood, and what is described as the dog type (atot si alaja). The perceived risk of contracting HIV is very low but it is acknowledged in the term eedi which describes the highest level of infection and improper treatment for that person. Aisan ti o gboogun which describes the general inadequate treatment of certain health conditions is also proper for those who contract HIV.[37]

Sexual Duties of a Wife

While it is socially acceptable for men to have multiple sexual partners while married, even sometimes endorsed by their aging wives, a woman doing the same is frowned upon. The adult children of women will sometimes monitor the activities of their mother to ensure she is not being promiscuous. The folk STI known as magun is a magical substance or curse placed upon a woman to punish her next sexual partner which could result in his death. It is seen as a punishment for sexual immorality.[38] The commonality of male extramarital affairs increases their risk for STIs much more than the risk for women.

Sex and Menopause

The body of a young woman is distinct from a man’s which displays her ability to procreate and her desire for sex. In aging women who no longer have the same level of attractiveness, her value comes from her children and her seniority. Since women had a duty to give their husbands sex whenever he pleased, aging offers some sexual liberation to women who might have found it painful. Beliefs surrounding the dangers of peri and post-menopausal sex discourage it.[39]

The dangers of a folk pregnancy or fibroid is called oyun iju. This is believed to occur when women beyond child-bearing age have unproductive sex resulting in a fibroid to which there is no treatment, rather than a baby. It is also understood that a woman over the age of 60 has the right to retire from her sexual duties to her husband. After having his children and being a good wife, she allows him to engage in extramarital affairs so she can focus on raising her children and grandchildren. For aging women, menopause is a legitimate reason to avoid sex. A woman’s sexual desire is not absent from her life as an elder but is detached from her duty to her husband.[39]

References

- Kola Abimbola, Yoruba Culture: A Philosophical Account, Iroko Academic Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1-905388-00-4

- Baba Ifa Karade, The Handbook of Yoruba Religious Concepts, Weiser Books, 1994. ISBN 0-87728-789-9

- William R. Bascom: page 43. ISBN 0-03-081249-6

- Yorùbá Online Yorùbá People And Culture: Yorùbá Language

- Fagborun, J. Gbenga, Yorùbá verbs and their usage: An introductory handbook for learners, Virgocap Press, Bradford, West Yorkshire, 1994. ISBN 0-9524360-0-0

- "Art History Made Visible / Studying Yoruba Art: Virtuoso Artists". africa.si.edu. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- Drewal, Henry John; et al. (1989). Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought. New York: Center for African Art in Association with H. N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-1794-7.

- Online, Tribune (September 21, 2021). "Esie: Inside Nigeria's first museum". Tribune Online. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- "Esie Museum". AllAfrica.com. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- "Esie Museum Kwara State :: Nigeria Information & Guide". www.nigeriagalleria.com. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- Mars, J. A.; Tooleyò, E. M. (2002). The Kudeti book of Yoruba cookery. CSS. ISBN 9789782951939. Retrieved April 8, 2015 – via Google Books.

- Ruth M. Stone (ed.), The Garland encyclopedia of world music, Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0-8240-6035-0

- Ogunyemi (Prince), Yemi D. (2009). The Oral Traditions in Ike-Ife. Palo Alto, California: Academics Press. ISBN 978-1-933146-65-2.

- Johnson, Samuel (1997). The History of the Yorubas. Michigan State Univ Press. ISBN 978-32292-9-X.

- Ogunyemi (Prince), Yemi D. (2003). The Aura of Yoruba Philosophy, Religion and Literature. Boston: Diaspora Press of America. ISBN 0-9652860-4-5.

- Ogunyemi (Prince), Yemi D. (1998). The Aura of Yoruba Philosophy, Religion and Literature. New York: Athelia Henrietta Press. ISBN 1-890157-14-7.

- "Málọmọ́". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Kòsọ́kọ́". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Káshìmawò". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Bánjókò". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Orúkọtán". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Yémiítàn". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Kòkúmọ́". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Dúrójaiyé". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Dúrótìmí". yorubaname.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Everything You Need to Know About the Money Dance Tradition". Brides. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- Mei-Mei., Murphy, Joseph M., 1951- Sanford (2001). Ọ̀ṣun across the waters a Yoruba goddess in Africa and the Americas. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-10863-0. OCLC 1340702142.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Okediji, Moyo (2015). "Yemoja: Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas, edited by Solimar Otero & Toyin Falola". New West Indian Guide. 89 (3–4): 424–426. doi:10.1163/22134360-08903049. ISSN 1382-2373.

- Kaufman, Tara (December 3, 2019). "Living Rivers". Athanor. 37: 89–96. doi:10.33009/fsu_athanor116677. ISSN 0732-1619.

- Barnes, Sandra T. (June 22, 1997). Africa's Ogun: Old World and New. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-11381-8.

- MAKANJUOLA ILESANMI, Thomas (1991). "The Traditional Theologians and thePractice of Orisa Religion in YorÙBÁLand". Journal of Religion in Africa. 21 (3): 216–226. doi:10.1163/157006691x00032. ISSN 0022-4200.

- Oyeronke, Olajubu (2004). ""Seeing through a Woman's Eye: Yoruba Religious Tradition and Gender Relations."". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 20 (1).

- Oyeronke, Olajubu (2004). ""Seeing through a Woman's Eye: Yoruba Religious Tradition and Gender Relations."". Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion. 20 (1).

- Beier, Horst Ulrich (1955). ""The position of Yoruba women"". Présence Africaine. 1: 39–46. doi:10.3917/presa.9551.0039.

- Beier, Horst Ulrich (1955). ""The position of Yoruba women"". Présence Africaine. 1: 39–46. doi:10.3917/presa.9551.0039.

- Essien, Kwame. "Cutting the head of the roaring monster" : homosexuality and repression in Africa. OCLC 707083061.

- Agunbiade, Ojo Melvin; Gilbert, Leah (June 2023). "Risky sexual practices and approaches to preventing sexually transmitted infections among urban dwelling older Yoruba men in Southwest Nigeria". SSM - Qualitative Research in Health. 3: 100252. doi:10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100252. ISSN 2667-3215.

- Agunbiade, Ojo Melvin; Dimeji, Togunde (August 20, 2018). "'No Sweet in Sex': Perceptions of Condom Usefulness Among Elderly Yoruba People in Ibadan Nigeria". Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 33 (3): 319–336. doi:10.1007/s10823-018-9354-8. PMC 6133031. PMID 30128832.

- Agunbiade, Ojo Melvin; Gilbert, Leah (March 29, 2019). ""The night comes early for a woman": Menopause and sexual activities among urban older Yoruba men and women in Ibadan, Nigeria". Journal of Women & Aging. 32 (5): 491–516. doi:10.1080/08952841.2019.1593772. ISSN 0895-2841. PMID 30922211.

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D. (Yemi D. Prince) "'The Oral Traditions in Ile-Ife, Academic Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1-933146-65-2

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D. (Yemi D. Prince) Yoruba Idealism (A Handbook of Yoruba Idealism), Diaspora Press of America, 2017, ISBN 978-1889601-10-6

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D. (Yemi D. Prince) Yoruba Philosophy and the Seeds of Enlightenment, Vernon Press, 2017, (ISBN 9781622733019)

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D. (Yemi D. Prince) The Aesthetic and Moral Art of Wole Soyinka, Academica Press, 2017, (ISBN 9781680530346)

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D. (Yemi D. Prince) "Yoruba Idealism, 2022: Peter Lang" ISBN 9781433190001

Further reading

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D. (2010). The Oral Traditions in Ile-Ife: the Yoruba people and their Book of Enlightenment. Bethesda, MD: Academica Press. ISBN 978-1-933146-65-2.

- Dayọ̀ Ológundúdú; Akinṣọla Akiwọwọ (foreword) (2008). The cradle of Yoruba culture (Rev. ed.). Institute of Yorubâ Culture ; Center for Spoken Words. ISBN 978-0-615-22063-5.

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D., Yoruba Idealism, published by Peter Lang, March 2022. ISBN 9781433190001, 9781433190018, 9781433190025, 9781433189753

- Ogunyemi, Yemi D., "Yoruba Philosophy and the Seeds of Enlightenment" Vernon Press, 2018, ISBN 978-1-62273-301-9