Wong Keen

Wong Keen (Chinese: 王瑾; pinyin: Wáng Jǐn, born 23 November 1942) is a Singaporean painter who was primarily trained in New York. He is known for being one of the first Singaporean artists to be educated in the United States and for his syncretic body of work that melds together the sensibilities of Chinese literati painting and the New York School.[1] His practice, unusual for his generation, has led to him being described as "Singapore's first abstract expressionist".[2][3] From 1969 to 1996, Wong also founded and operated Keen Gallery in New York, a framing studio and exhibition space.[4]

Wong Keen | |

|---|---|

| 王瑾 | |

Wong Keen in his studio, 2018 | |

| Born | 23 November 1942 Singapore |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | The Chinese High School, Singapore The Art Students League, New York, USA Saint Martin’s School of Art, London, UK |

| Known for | Oil painting, acrylic painting, ink painting, collage |

| Style | Nanyang School, abstract expressionism, colour field painting, action painting |

| Website | https://www.wongkeen.com/ |

A protégé of the pioneer artist Chen Wen Hsi while also training under Liu Kang, Wong counts among the second generation of Singaporean artists.[1] His early works bore distinctive features of the Nanyang School, with an emphasis on cubist and fauvist modernist ideas. After enrolling in the Art Students League of New York in 1961, his practice has broadened to include influences from abstract expressionism, colour field painting, and action painting, all the while maintaining an affinity with Chinese calligraphic aesthetics and the idiosyncratic compositional forms of Bada Shanren.[1][5]

Wong's preferred media reflects his diverse aesthetic inheritance and includes oil paint, Chinese ink and colour, acrylic paint, and collage, executed on canvas, archival paper, and rice paper. Preferring to work with the same subject matter over long periods of time, Wong's oeuvre has often been categorised serially, with his paintings of nudes, lotuses, and flesh being particularly prominent.[5][6]

Wong Keen's practice is currently based in Singapore.

Early life (1942–1961)

Family

Wong Keen was born in the first year of the Japanese Occupation, the second child of Wong Chennan (Chinese: 王震南; pinyin: Wáng Zhèn Nán) and Chu Hen-Ai (simplified Chinese: 朱恒霭; traditional Chinese: 朱恆靄; pinyin: Zhū Héng Ǎi). Both were teachers, at the Chinese High School and the Nanyang Girls' High School respectively.[4][7] The family resided at the Chinese High School Teachers' Quarters, part of a social circle that included pioneer artists such as Chen Wen Hsi, Liu Kang, Cheong Soo Pieng, and Chen Chong Swee, all of whom taught at the Chinese High School during Wong's formative years.

Both Wong sr. and Chu practiced Chinese calligraphy, and can be classified among the literati calligraphers of early Singapore. These calligraphers inherited the aesthetic sense of amateurism (as opposed to the professionalism of court painters) of dynastic Chinese scholar-officials, favouring spontaneity and an affinity for literature and belle lettres.[8] Chu was especially serious in this pursuit, participating in many group exhibitions and even holding her own solo exhibition in 1997.[9][10] This familial setting would have an enduring influence on Wong; his early New York days would be marked by explorations into calligraphic aesthetics, and he would produce collages that fragmented and reassembled his mother's calligraphy throughout his career.

The Chinese High School shared many of its art teachers with the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) at this time and was an important incubator of young artistic talents. Departing from the earlier pedagogical directions of Richard Walker,[11] who served as Art Superintendent Singapore Schools before the War, the Chinese High School's art education was grounded in modernism (particularly the School of Paris). The resources and emphasis the Chinese High School placed on art education was exceptional among schools in Singapore. Among its students that later took on a career in the fine arts were Ho Ho Ying and Goh Beng Kwan, both of whom were childhood friends of Wong.[12]

Wong enrolled in the Chinese High School from 1955-56.

Learning to paint

Impressed by her son's sketches of figures in magazines, Chu arranged for Wong to take drawing lessons from family friend Liu Kang. Wong was then aged around 10-11.[9][12] Wong soon went on to take more technical lessons with Chen Wen Hsi, focusing on oils and Chinese ink. Wong's relationship with Chen would become especially close and shaped Wong's early career. In 1957, Chen moved out of the Chinese High School Teachers' Quarters into his home and studio at 5 Kingsmead Road, where he hosted close students and conducted more in-depth art lessons.[13] Between 1957 and 1961, Wong was a regular visitor to 5 Kingsmead Road, together with a group of friends that included Goh Beng Kwan. Wong worked on the in-situ mural Chen designed for his residence.[13]

The years Wong studied with Liu and Chen was a formative period for modernist Singaporean art, later known as the Nanyang School of Art. Both Liu and Chen were involved in exhibitions that would later be recognised as foundational moments in the development of the movement. The Nanyang School of Art, or Nanyang Style, has been defined by art historian T. K. Sabapathy as a synthesis of Chinese ink scroll and School of Paris pictorial schemas, with an emphasis on subject matter that portrayed the reality of Southeast Asia.[14]

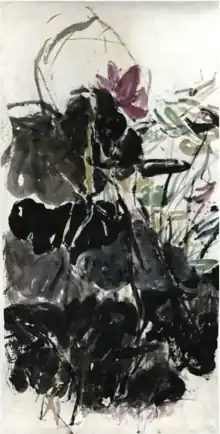

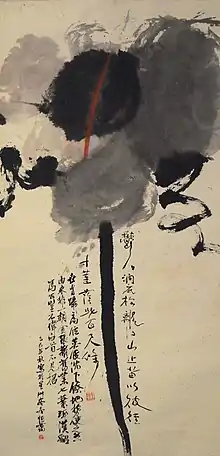

Wong's early practice was influenced by the Nanyang School, as refracted through Chen. Specifically, Wong inherited Chen's emphasis on cubist and fauvist ideas.[15][16] This aesthetic direction is especially obvious in the oil painting Bicycle (1959), "demonstrating the teenager's interest in the cubist fragmentation of a flat pictorial plane and stark angular forms".[1] Wong's early Chinese ink paintings were also affected by Chen's practice. Lotus (1956) exhibits tonal wash qualities valued by Chen, through his study of Bada Shanren, but with modernist compositional sensibilities.[1] Perhaps more evident in his oil paintings, Wong's subject matter also conformed to the ideals of the Nanyang School—to depict the lived reality of Southeast Asia.[14]

Entry into the art world (1957–1960)

Wong's prodigious talent began to draw attention as he started to participate and exhibit in Singapore's broader art world. In 1956, he won the first prize in the 'C' Category of the Shell Art Competition. From 1957-1960, Wong was selected to show his works at each of the Singapore Art Society's Annual Open Exhibition; the invitation in 1957 made him the youngest artist (at the age of 15) to have shown in this series of exhibitions.[4][17] These exhibitions were juried by the leading Singaporean artists such as Ho Kok Hoe, Georgette Chen, and Cheong Soo Pieng, and were one of the main venues through which aspiring artists established themselves.

His first major commission came in 1960, to paint a mural for the Lido Cinema on Orchard Road, operated by the Shaw Brothers.[4] Due to Wong's departure from Singapore the next year, this commission was not fulfilled.

Wong's unusually young age was noted by the art community. Sin Chew Jit Poh introduced him as "one of Singapore's daring new painters"..."with his youthful ability and genius, he will bring extraordinary splendour to Singapore's art world."[17] Chen Wen Hsi commented that "looking at these paintings, no one will believe that they were completed by a 19-year-old youth".[15]

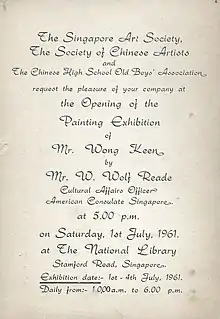

First solo exhibition (1961)

In 1961, following the acceptance of his application to the Art Students League of New York, Wong Keen held his first solo exhibition to fundraise for his studies.[18] This exhibition, held at the National Library from July 1–5 (with an extended day),[16] made 19-year-old Wong the youngest Malayan artist to hold a solo show. The exhibition was co-organised by the Singapore Art Society, the Society of Chinese Artists, and the Chinese High School Old Boys' Association.[4][17]

The exhibition was very well-received, with 70 of the 75 exhibited paintings sold.[4][18] Among the notable patrons of Wong's paintings were Lee Kong Chian, Tan Tsze Chor, Chng Pee Tong, and Tan Kong Piat.[19] Lee purchased the most expensive painting on display at $700.[4]

The Chinese-language newspapers ran a considerable amount of articles that featured the exhibition which together formed Wong's first sustained public exposure. The exhibition also featured in Marco Hsu's seminal work A Brief History of Malayan Art.[20] Chen Wen Hsi wrote that "within my current students there are many with a talent for painting and a bright future. Wong Keen, who will shortly depart for his overseas studies, is exceptional within this group."[15] Ho Ho Ying concluded the reportage with this appraisal:

"Although he is mainly cubist in method, he is not restricted by cubism; the colours of fauvism and the imagery of abstract painting also play an important role in his art. He works to attain the most beautiful harmony within these three styles. With his industry, I believe that he will become an exemplary Malayan painter."[16]

Wong Keen departed Singapore in the same year on a freighter bound for New York with $200 for his expenses; the rest of the exhibition's proceeds went to his family.[4]

Moving to New York (1961–1966)

Art Students League

New York of the early 1960s was where abstract expressionism had matured and been well-established; Stella Paul describes a "first generation" of abstract expressionists from 1943-mid 1950s that "effectively shifted the art world’s focus from Europe (specifically Paris) to New York in the postwar years".[21] This departure from Parisian modernism (which heavily influenced the Nanyang School) was a major factor in Wong Keen's shift away from his previous practice.

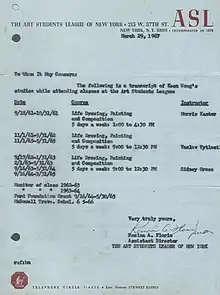

The Art Students League, which Wong Keen enrolled in from 1961-1966, played a significant part in educating a new generation of artists working with recourse to abstract expressionism.[5][22] Wong enrolled in the Life Drawing, Painting and Composition course instructed by faculty members Morris Kantor, Vaclav Vytlacil, and Sidney Gross over the period 1961-1965. The course required Wong to dedicate 3.5 hours a day, 5 days a week.[9][5] Wong earlier years in New York were marked by a degree of poverty, requiring him to take up part-time jobs on top of selling his paintings.[23] Following the award of the League's Ford Foundation tuition scholarship in 1964, which covered the cost of one course of his choice, he was able to concentrate more on his practice.[4]

New York's intellectual atmosphere also allowed Wong to access the works of other New York School painters, many of whom will continue to influence Wong throughout his career. Among the most commonly cited sources of influence were Willem de Kooning, Francis Bacon, Richard Diebenkorn, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, and Mark Tobey.[1][5][24] Part of Wong's study was outside of his curriculum at the League, as he sought out, interacted with, and gained insights from pioneering abstract expressionist artists such as Hans Hofmann and Theodoros Stamos.[25] He visited the night classes of Theodoros Stamos on several occasions where they conversed on the subject of art and painting.

Of note among the various art forms that Wong acquainted himself with was the relatively young style of colour field painting. The painter Hans Hoffman, who was a champion of colour field painting, interacted with Wong through the League.[24]

Wong's pioneering presence in New York was also notable for the role it played in Singaporean art history. The first notable artist of his generation to reside, practice, and study in the complex New York art world, Wong paved the way for later artists such as Goh Beng Kwan, Choey Kwoy Kay, and Chow Yin Tian to train in New York, personally guiding them through their application processes and shared his 2000 sq ft lodgings on Broadway with them;[1][23] Goh would be the next notable artist to be accepted at the Art Students League, in 1962.[26] He was also one of very few artists of Chinese origin based in New York at that time.[27]

Solo shows (1963–1965)

Wong produced a significant body of work as a student. He was reported in the New York World Telegram and Sun as having "painted almost 200 pictures since his arrival here a year ago".[28] These works would form the basis of two solo exhibitions held in New York.

Wong's second solo exhibition was held at New York's Bridge Gallery from 9–27 April 1963, perhaps the first solo exhibition a Singaporean staged in New York.[23][29][30][31] The Nanyang Siang Pau reports that "Wong Keen exhibits 25 large-scale oil paintings, the largest of which were 8 x 6 feet, the smallest of which was 4 x 3 feet, and 30 ink paintings, all completed in America."[30] An appraisal by his lecturer Sidney Gross was published and translated in both American and Singaporean newspapers:

"I remember vividly the first time I saw his watercolours [sic] and drawings. They're lyrical, extremely suggestive and filled with a special sensitivity he could only have inherited. Although they were quite abstract and informal, I felt all the traditional Chinese influences very beautifully integrated. Wong Keen is a very gifted young man and I have enormous confidence in his future."[31][32]

His next solo exhibition was held from 27 Feb-18 Mar 1965, at Westerly Gallery shortly after he was awarded the Ford Foundation tuition scholarship.[32][7] As accounted by gallery manager Suzanne Varady, "when I first saw his work early this winter I was so impressed I immediately set about arranging an exhibition."[33] The works in this exhibition seemed to have made an impact in the way Wong's practice stood between Chinese aesthetic influences and Western modernism. Sidney Gross commented that "Wong was one of a group of talented painters here [New York] trying to assimilate many Western ideas without losing their own identity."[33] The Taiwanese artist and writer Ho Tiehhua (simplified Chinese: 何铁华; traditional Chinese: 何鐵華; pinyin: Hé Tiě Huá), then based in New York, wrote a lengthy commentary:

"... Wong's paintings cannot be compared to the usual 'new-style' paintings that are without substance. This is because he is well-versed in the old, and his works do not appear to be without basis. Westerners are too concerned with structure, but the Chinese emphasise an immediate reaction to stimuli. Wong understands this deeply, and is thus able to shake off the shackles of the past. He departs from tradition from the basis of tradition, accepting the thoughts of the new age. With this, he is able to inherit the spirit of painting passed down from the Tang and Song dynasties, creating new Chinese paintings that are international in essence."[32]

Europe (1965–1966)

Wong Keen soon won the Art Students League's Edward G. McDowell Traveling Scholarship for 1965, the first painter of Chinese origin to do so.[34][35] The scholarship required Wong to undertake a part of his studies in Paris and other European countries, and carried the stipend of $3,000 per annum.[34][36]

Before his travels, Wong was invited to deliver a lecture on Chinese painting and to stage a solo exhibition of his ink paintings at Fordham University, New York.[4]

Wong returned to Singapore on 28 June 1965 to spend time with his parents before embarking on his European tour.[37] In his stay, he executed a series of ink paintings that elaborated on the abstract ink expressions he developed in New York, but with a greater emphasis on the white space compositional device of Bada Shanren.[1] These paintings bore the inscriptions of one or both of his parents (such as in Run in the Family II, 1965) and signified towards the later Caesura series of collages that bore similar familial themes.[5][1]

Later in the year, Wong departed Singapore and arrived in Europe via India and Pakistan. He would visit Athens, Copenhagen, Paris, Rome, Cologne, and London. Chen Wen Hsi joins him in Germany and London.[4] Wong eventually decides to join a programme in London's St. Martin's School of Art, engaging in sketching as well as "making full use of the opportunities provided by museums and galleries".[38]

The works produced in Europe garnered interest in the Western art world, resulting in three solo exhibitions: St. Martin's School of Art (1966, at the request of Principal Edward J. Morss), Sarah Lawrence College, New York (1967), and The Art Students League, New York (1967).[4] Although he also showed oil paintings,[39] Western media seemed more interested in his ink paintings:

"In this show [at the Art Students League], the paintings, ink-wash drawings and scrolls with Chinese calligraphy were in part produced during the time he spent in England. Although his art is more western than eastern in basic direction, a number suggest both the influence of the modern Chinese painter Chi Pai Shi [Qi Baishi] and the Ching dynasty painter Zhu Ta [Zhu Da, a.k.a. Bada Shanren]."[40]

Wong Keen returned to New York in 1966 and graduated in the same year.[4]

Idiosyncrasy

Wong's student years in New York were a new formative period, where he turned away from earlier Nanyang School practices into more contemporary aesthetic ideas. The innovations of this period shaped Wong's trajectory and development, and developed in a body of idiosyncratic paintings.[1]

Wong's exposure to colour field painting and its proponents led to a new sensitivity to colour that stood apart from other contemporary Singaporean painters. Among the ideas Wong garnered from the style was the "employment of low-key contrasts between colours for details to surface" and "the direct placement of vivid colours next to each other", resulting in a "push-and-pull interaction" within his works that stems from colour rather than composition.[24]

His new ideas about the function of colour was coupled with a personal take on gestural brushstrokes, especially in relation to action painting.[24] Through the ideas of Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell, action painting drew inspiration from the expressive potential of East Asian calligraphy.[1] Wong brought into gestural strokes the idea of colour tonality, derived also from East Asian calligraphy and his training in the Chinese ink medium.[24] For Wong, calligraphy is also more than an art form and carried familial connotations, inspired from his parents' practice.[1] As such, Chinese characters often appear in his paintings (such as in Untitled, 1964), facilitating the autobiographical element that has been detected in his paintings, allowing him to stake his own position in the internationalist modern art world.[5][24]

Antony Nicholin and Peter Stroud wrote of this synthesis:

"Utilising gesture as a primary expressive vehicle, Keen's paintings vary from a highly personalised lyrical figuration to extreme abstraction. In these works, one also sees evidence of his concerns with the essentials of Colour-Field painting—a strongly reductive aesthetic emerging with an emphasis on an all-over surface."[41]

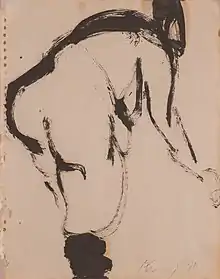

One of Wong's most important series of works—the nude—started to become part of Wong's practice around 1962.[5][42] Commenting on a representative work of the period, Arms Stretching (1963), Ma Peiyi observes through the circular structuring of Wong's nude forms his attempt in engaging more stylistically with the shape of his subjects "without compromising on [their] basic anatomical proportions."[24] Wong's friend and fellow artist Choy Weng Yang wrote of the same painting:

"Arms Stretching (1963) is a highly sophisticated and intriguing work in Wong Keen's nude painting series. The piece comprises exceptional artistic characteristics—an outcome of the artist's intensive search for innovative approaches extrapolate the tantalising visual essence of an irresistible artistic theme. The extreme limitations imposed by the deliberate grey colour scheme to achieve a work of unifying visual nuances make it virtually impossible for the artist the forge a work of clarity and eloquent articulation. But Wong Keen takes this as a challenge."[43]

In his ink paintings, Wong sought out a midway between two traditions, much as commentators have often recognised in the newspapers.[31][32] Bringing the gesturalism of action painting and modernist compositional sensibilities into the realm of calligraphic strokes, Wong's early New York ink paintings thus reflected "an urgent need to re-evaluate 'the sublime nature of abstraction that long defined the Chinese ink culture.'"[44] Roy Moyer commented that "when he arrived in New York in 1961 to study at the Art Students League, he was quite comfortable with abstract expressionist art, since there is nothing more abstract than those Chinese calligraphic ideograms which he knew so well."[42]

Chen Wen Hsi's presence at the start of Wong's European trip may have further honed in Wong's attention to the art of Bada Shanren; besides being influenced by Bada Shanren, Chen was a renowned collector of Chinese art that included a celebrated album of Bada Shanren.[4][45] Lotuses would enter Wong's oeuvre in this period, producing semi-abstract ink paintings such as Lotus (1965), providing Wong a vehicle through which he may more intuitively explore the relationship between Chinese ink painting and Western modernism.[46][43] Commenting on this series, Ma Peiyi wrote:

"Wong Keen's crucial search for a direction to advance and integrate Chinese ink expression in his synthesis of East-West abstraction styles gave rise to a unique series of abstract ink wash paintings during the period of 1962-65. Utilising Bada's sparse yet expressive compositional style as a scaffold for pictorial innovation, the series is empty of imagery but striking in its poetic subtleties; form and atmosphere are evoked through delicate spatial arrangements and rhythmic, gestural brushstrokes."[47]

Wong would develop his intrigues into Chinese ink gestures and expressions further in a series of nude paintings (of a model named Susie), executed with oil on paper in the Chinese freehand style.[48]

Making a living (1967–1996)

Keen Gallery (1969–1996)

After his two solo exhibitions in 1967, Wong found a job as Art Director at the Police Athlete League, New York. He worked in the job until 1969, setting up Keen Framing Gallery in 1969. This allowed him to continue working on his own practice while keeping in touch with the wider art world.[4][49] His framing services were popular, garnering clients such as the Museum of Modern Art, Time Magazine, the Rockefeller Foundation, and Macy's.[50] He was known for his artisan framing services, providing framing design with artistic sensibilities.[50]

Keen Gallery moved to 423 Broome Street in 1971, expanding to include a gallery business.[4] Though mainly staging curated exhibitions of other artists, Wong also sold some of his own paintings through Keen Gallery.[4] Artists represented or exhibited by Keen Gallery included Patrick O'Brien, Serge Lemoyne, Lee Shi-Chi, Jenny Chen, Ming Fay, Camilo Kerrigan, Edward Evans, Tino Zago, Dennis Hwang, Michiko Edamitsu, George Bethea, and Norman Barish.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59] Keen Gallery also hosted a reading of poems by Pang-cheng Peng and the play Prism View by Joe Fox.[60][61]

Perhaps the most important exhibition put up by Keen Gallery was Red Star Over China: Tenuous Peace, held from 5 May - 5 June 1993.[62] The group show featured artworks by artists Liu Xiaodong, Cha Li, Chen Xiaohong, Hao Zhiqiang, Hou Wenyi, Lin Lin, Ma Kelu, Ni Jun, Xia Baoyuan, Yu Hong, Zhang Zeping, Zhao Bandi, and Zheng Dasheng. The artists were largely young Chinese contemporary artists, some of whom were the first generation to base themselves overseas after the Cultural Revolution.[63] The exhibition was one of the earlier showings of Chinese contemporary art in the United States.[62][64]

In his time operating Keen Gallery, Wong formed a friendship with the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, the Taiwanese-American artist C. J. Yao, and the Chinese violinist Xu Weiling. They would meet almost every week in the 1980s.[4]

Wong's art practice was disrupted by the business of Keen Gallery and he would not be able to dedicate himself to painting fully until the late-1980s.[4][12] He was reported in 1971 as hoping to send recent paintings to Singapore for Chen Wen Hsi to organise into an exhibition, but that did not materialise.[49] Though his output was limited in this period, it was still marked by a developed interaction with form within his paintings, particularly as he settled on his preferred subject matter and worked to stylise them. Commenting on a work of this time, Kwok Kian Chow and Ong Zhen Min wrote:

"In an earlier work, Lotus Metamorphosis (1987), the lotus is a highly abstracted form floating in a background of green. Hence, the lotus is an important focus in understanding how Wong Keen experiments and ventures into different areas of stylistic expressions in his works."[5]

Speaking of this period, Wong recounted:

"For over twenty years, my heart was bombarded by the same question every day, 'When can I finally go back to my painting?'"[25]

Returning to exhibitions (1987–1996)

Wong returned to the exhibition circuit in the late 1980s after personal and professional commitments realigned, allowing him more time to dedicate to his practice.[4] Wong first participated in the 1987 group exhibition The Commemoration of the Nanking Massacre, sponsored by the Chinese Alliance in New York. Soon after, his contacts with Taiwanese artists established through Keen Gallery resulted in two solo exhibitions in 1988 and 1989, at El Museo de Arte Costarricense, Costa Rica, and Gallery Triform (simplified Chinese: 三原色艺术中心; traditional Chinese: 三原色藝術中心; pinyin: Sānyuánsè yìshù zhōngxīn), Taiwan, respectively.[4] This was 21 years since his last solo show. Thereafter, Wong participated in a series of group shows in New York until his started to base part of his practice back in Singapore. Two of Wong's works were collected by the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, New York, after a group exhibition there in 1994.[4] Wong held his 10th-12th solo exhibitions between 1994-1995, at the William Whipple Gallery (Southwest State University), Gilwood Haven Art Gallery, and Carnegie Art Centre respectively, all in the state of Minnesota.[65]

Among Wong's output in this period, two distinct series of works emerged: the Torso and the Caesura series.[1]

Torso series (1986–1996)

The Torso series began as a new approach to the nude, manipulated through simpler geometric planes and solid colour blocks. These nudes were often disembodied, focussing on the points in which their torso meets their legs. These nudes were "[depicted] in the two-dimensional as opposed to the conventional method of three-dimensional realism, thereby introducing a sense of flatness to his work."[5] Antecedences to the Torso series were first exhibited at Gallery Triform, Taiwan, where 20 "recent works, mostly abstracted forms inspired by female nudes" were shown.[66][67] A review of the exhibition remarked that "Wong Keen's recent works were mostly based on the human form; with twisted brushstrokes he retained his usual abstract style."[68] The Torso series resulted as an elaboration of this earlier series of nudes exhibited in Taiwan, executed mainly between 1986-1996, with the important introduction of paper collage techniques (reminiscent of paper collé) that further flattened parts of the nude composition.[1]

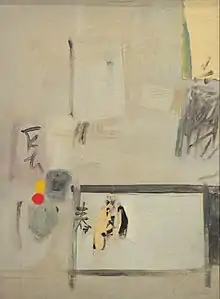

Caesura series (mid-1990s–)

The Caesura series manipulated his mother Chu Hen-Ai's calligraphy and his own take on calligraphic strokes through the combined use of ink, paper collages, and acrylic paint, applied on rice paper.[69] Wong's use of acrylic paint was unusual in how it referenced the fluidity of ink in Chinese paintings. This series formed perhaps Wong's clearest repudiation and redefinition of the traditional inspirations and cultural moulds that shaped his practice, as Kwok and Ong have written: "Caesura works on the theme of destruction and rebirth. These works combine scraps of traditional Chinese prints and calligraphy on paper, juxtaposed with ink washes and acrylic shapes. In this manner, traditional Chinese art is fragmented and remade into new forms."[5][24] In a 1994 interview about his Caesura series, Wong Keen explained:

"I was not looking for the relationship between the words and the painting except for their formation, and I often use broken words and sentences instead of whole symbols... I think I am subconsciously trying to recreate the look of the calligraphy. The paper gets torn and squashed to represent the different stroke forms [in the calligraphy]. It is this use of shape that serves a purpose and gives meaning and expression to the painting."[69]

Back in Singapore (1990–)

Renewing contacts (1990–1996)

From 1990, Wong started to spend more time in Singapore to tend to his mother's ailing health.[4][70] Although most of his practice was still based in the United States, where he continued to hold exhibitions, he began to reconnect with the Singaporean art world and his old friends. As recounted by Wong: "I had been trying to come back (to exhibit) for years... I still have a fascination with Singapore. I come back to visit whenever I have the chance."[71]

In 1995, Wong planned to hold an exhibition of Singaporean artists in Keen Gallery to increase the Singaporean presence in the New York art world. He found that "working there [New York] as part of a small group of Singaporean painters can be quite lonely sometimes".[70] The planned exhibitors were Chng Seok Tin, Choy Weng Yang, Goh Beng Kwan, Goh Ee Choo, and Yeo Kim Seng.[72] Though the exhibition was reported in the newspapers, it did not materialise due to a lack of funds.

Wong decided to close down Keen Gallery and formally base part of his practice in Singapore in 1996.[4]

Homecoming (1996–2007)

Wong became acquainted with gallerist Gim Ng of Shenn's Fine Art in the 1990s. This relationship culminated in Wong's first large-scale exhibition in Singapore since he left in 1961, titled After Thirty-Five Years in New York (1961-1996). The exhibition was held at Takashimaya Gallery, Singapore, from 3–11 August 1996. Wong described the experience as "a kid coming back with his report card after 35 years".[70] The exhibition featured "more than 50 of his works spanning four decades, from the '60s to the '90s".[70] Being his first retrospective exhibition, Wong took the chance to take stock of his career in a newspaper interview:

"I divide my development by decades. Before and during the 1960s, I studied Chinese ink paintings. After a year of discovery in the United States, I could only paint as I wished in the second year. Because I was expressing myself freely, it became a style, although it was still pictorially influenced by abstract painting and some techniques of Francis Bacon in England. In the 1970s, I found the creative potential of abstract expressionism. In the 1980s, I quietened down and started to be acquainted with the works of the Qing dynasty painters Bada Shanren and Shitao. In the 1990s, through my memories, I expressed Chinese landscapes and customs."[73]

The 1996 exhibition garnered much media attention and worked well to reintroduce Wong to the Singaporean art world that developed in his absence. Relationships built with individuals such as Tommy Koh and Koh Seow Chuan resulted in the landmark retrospective Wong Keen: A Singapore Abstract Expressionist, held in the Singapore Art Museum from 9–29 March 2007.[74] The exhibition was preceded by Koh Seow Chuan's large donation of 63 paintings by Wong Keen to the Singapore Art Museum.[75][76] These works ranged "from those he painted in the United States in the 1960s to more recent ones that were done in Singapore".[77]

Wong's body of work was contrasted by commentators to the School of Paris-inflected style of painting that shaped the practices of Wong's Singaporean contemporaries; its presence in the National Collection was noted to "enable the museum to broaden the scope of its permanent collection to more fully present the history of Singapore and Southeast Asian art in its galleries".[75] The exhibition framed Wong as "a Singapore chapter to Abstract Expressionism", recognising that the movement was itself internationalist and amenable to interpretation in specific contexts.[5]

In the same year, Wong's painterly origin was given a further spotlight when he was shown at the National Art Museum of China, Beijing, together with his mentor Chen Wen Hsi and friend Goh Beng Kwan, exhibiting 15 artworks each from the National Collection. The exhibition was titled Encounters and Journeys: Singapore Artists (simplified Chinese: 游·遇·艺:新加坡艺术家; traditional Chinese: 遊·遇·藝:新加坡藝術家; pinyin: Yóu·Yù·Yì: Xīnjīapō yìshùjiā) and ran from 12-21 Oct 2007.[78] The exhibition was part of Singapore Season 2007, an exercise in cultural diplomacy.[79]

A renewed practice (1996–)

Since returning to Singapore in 1996, Wong has been represented by a series of art galleries in Singapore (including Shenn's Fine Art, Galerie Belvedere, and artcommune gallery) as well as taking up residencies and holding exhibitions in Asia. Able to spend much more time and energy on painting, Wong's practice saw a period of intense productivity, resulting in the renewal and consolidation of his aesthetic thoughts into several distinct series of paintings.[4] Wong's practice did not entail of periods that succeeded each other, resulting in many overlapping series and outlying works.[1][24]

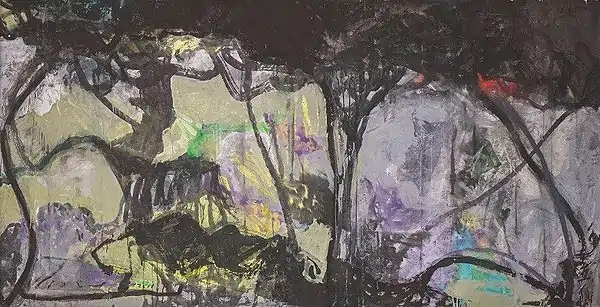

Landscapes and figures (1996–mid-2000s)

Wong's interest in the genre of landscape painting was reignited by his return to Asia, taking references from the Chinese landscape tradition as well as classical and contemporary Asian environments. There is no widely accepted name for this series, and it has been termed variously as the "composition series" or "lotuscapes".[43][80] These landscapes were a syncretic expression of Wong's practice thus far, incorporating within a single image the subject matter of landscapes, lotuses, and female forms (nudes and clothed).[81] Landscape contours itself were often depicted as inherent within the forms of lotuses and nudes.[5] The use of the painted image as an assemblage of ideas was also important, as Goh Kay Kee described: "All that exists in the image are absorbed and transformed by lines and colour planes, which the artist called a method of 'composition'".[80]

_1998_oil_on_canvas.jpg.webp)

The post-1996 series of landscapes were first shown at Caldwell House Gallery, CHIJMES in August 1997, organised by Shenn's Fine Art.[4] This initial set of works from this series was largely completed from 1996-1997 as Wong moved back to Singapore and travelled through Thailand, Bali, Java, and China, incorporating the new images of Asia he garnered into his paintings.[81][43] A distinct but related series of Vietnam paintings were inspired by Wong's visit to Huế in 1987, and was exhibited in Gallery Vinh Loi, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam and The American Club, Singapore in 1998. The Vietnam paintings are distinguished by a relatively strong sense of realism and figurative elements.[82][80]

Wong's emphasis on colours were reiterated here as "colour bar theory", where he "mark off areas of the canvas as windows, or mini paintings within the larger whole. The horizontal and perpendicular lines usually trace the development of a single colour from its light stage through all permutations to dark".[81] Most of these paintings were executed with oil on canvas, though Wong later delved into acrylic paint.[82]

Nudes, especially with monumental landscape-like compositions, continued to be a part of Wong's practice, all the way to the 2010s; the separation of these later nudes from the landscape/nudes of 1996-7 is unclear.[6][43] Wong would also gradually move into the use of acrylic paint as his main canvas medium, rather than oil. As a commentary of an acrylic nude painting of 2007 elaborates:

"In a composition like Big Nude, we encounter all the prevailing inclinations that have come to define Wong Keen's visual language. The truncated female form occupies a sensual dimensions made up of vivid hues and rich spontaneous undercurrents of interlaying strokes. The overall pictorial arrangement is almost akin to a landscape, possibly intended by the artist. Her body flows along seamlessly although its white luminosity carries a somewhat opposing tune against the bright, lush colours that furnish her well-defined contours."[24]

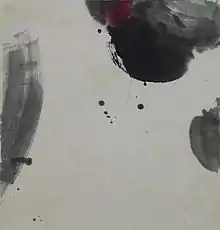

Formation series (1997–1999)

The Formation series can be traced to Wong's Vietnam paintings, where he described his lotus oil paintings as "formations" (simplified Chinese: 构成; traditional Chinese: 構成; pinyin: Gòuchéng) in interviews.[82][80] This series is centred on the subject matter of lotuses and the compositional potentials of its form, whether in the textures of its leaves or petals or the way its stalks section the image. Though some commentaries have posited on the symbolism of the lotus ("Buddhist imagery" and "Chinese aesthetic heritage") and marked "a return to content and symbolism in the artist's work",[5] others have argued that "Wong Keen's adoption of the lotus as a recurring motif has less to do with its spiritual symbolism than the multitudinous form it affords as a vehicle for expressing form and colour".[1]

The Formation series is diverse in media, straddling oil on canvas, acrylic on canvas, Chinese ink and acrylic on rice paper, and oil on paper.[1] Wong's use of acrylic paint in place of or in conversation with traditional Chinese pigments is especially notable, as he "took to exploring more opaque and weightier body in the form of oil or acrylic paint to render an affective subtlety more usually associated with Chinese ink-wash".[83]

Bada Shanren's lotus paintings were a particularly important source of inspiration; Wong worked with reference to a Bada Shanren catalogue.[1] The series worked to bring Bada Shanren's idiosyncratic compositions and colour field painting into conversation, as Wong explained: "Bada's paintings are without colour; I have coloured them in".[76] Commenting on a representative work on rice paper, Ma Peiyi wrote:

"In the case of Lotus XX (1999), Wong Keen appears to have unified the spatial approach of Bada with that of another Western artist he deeply admires, Richard Diebenkorn. While the composition reads entirely abstract when comprehended through the relations of colour, line and shape, a lotus pond becomes visually apparent once the viewer subsumes the image within the signified context of its title. Within the artists's ingenious conception of space, the lotus form is absent but present, and is judiciously employed to segment pictorial elements."[1]

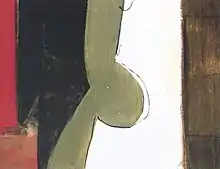

Picture writing (2009–2012)

Picture Writing, executed largely between 2009 and 2012, elaborated on Wong's study into calligraphic expressions and "may be viewed as an extension to his earlier series on the calligraphic female nude [the 'Susie' nudes]".[24] It consists mainly of acrylic paint on paper works, though Wong also executed some nudes with oil on canvas and painted ceramics.[84]

This series is mostly minimalist in colour but with varied monochrome tonalities—an adaptation of the techniques and aesthetics of monochrome Chinese ink wash paintings and calligraphy.[1] As opposed to Wong's earlier nude forms, the Picture Writing nudes tended to be more angular, their proportions blown up, and are laid on a field of negative space.[84][85] The influence of Chinese freehand painting (simplified Chinese: 大写意; traditional Chinese: 大寫意; pinyin: Dàxiěyì) is especially strong in this series.[24] As introduced in the exhibition catalogue:

"In these ink expressions, the female nude that flows into form through his dynamic and fluid brushstrokes move through light, sensual space; is devoid of identification yet concrete in her evocative gesture. Even when he has chosen for the figure to be submerged within an abstracted landscape, the lines and contours relate sensuously to each other, resulting in an arresting composition."[84]

Acrylic on paper works (2013–)

Wong produced two series of paintings on rice paper—Second Nature and Orbits of Colour—in the 2010s. These paintings continued Wong's innovative ink-like use of acrylic pigments on rice paper, and can be considered an elaboration of the Formation series.[1] Both Second Nature and Orbits of Colour series were first shown in solo exhibitions held at artcommune gallery, in 2014 and 2016 respectively.[83][44]

The Second Nature paintings were largely produced from 2013-2014. Second Nature featured a rudimentary printmaking technique where "the artist first executes an acrylic composition on a laminated board; a sheet of rice paper is then pressed over the board, with the composition rubbed through to create the first layer on the rice paper. This process is repeated another few times until the artist is satisfied with the layers of pictorial effects. The final composition is then painted directly onto the rice paper, leveraging the existing formation of colours and textures."[1] The series was also informed by Wong's collage practice, which complicates the dimensional qualities of the image.[83]

Orbits of Colour emphasised the interaction between soft-edged colour zones and the spontaneous application of pigments, as expressed through brushwork and aleatoric effects such as drips.[44][1] This series demonstrates an "inexorable move toward the liberating use of colour even as Bada's influence remains an unconscious anchor", and is within the aesthetic genealogy of the Formation and Second Nature series.[1] Orbits of Colour is notable for a group of monumental paintings, the largest of which measures around 150 x 300 cm.[44]

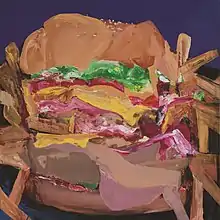

Flesh (2012–)

The origins of the Flesh series can be traced a series of oil on canvas works that were executed in Beijing, 2012, during an artist residency Wong had undertaken at the Galerie Urs Meile.[86] This series was later fully elaborated from 2015-2018, when Wong transferred his initial exploration of Flesh into a sustained series that were mostly acrylic paint on canvas or paper and collages. The pictorial vocabulary of Flesh would come to include the carcass, the meat shop, burgers, and nudes.[87] The process through which Flesh came to be incorporated within the artist's practice was, as described by Wong:

"I was very much attracted to these meat stalls in the market. The shape of the meat, the colour of the meat, and when the sunlight come in and shone on the meat; the rhythm of the ribs that came from one end to the other formed a very nice composition to me... very quickly I was inspired to do some work on it, so I went back to the studio and started making some paintings. The outcome was about 13 oil paintings of different sizes—most of them huge."[86]

Wong's use of the subject matter of Flesh to explore formalist qualities such as "shape, colour, and rhythm" was influenced by the Flesh paintings of Rembrandt van Rijn, Chaïm Soutine, Francis Bacon, and Willem de Kooning; de Kooning himself remarked that "Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented".[87][88] The pictorial language of Flesh is also a metaphor for what Wong understands us society's habit of mindless consumption, especially of women; this is expressed through the mutually implicated forms of fast-food burgers and the female nude.[89][87] As expressed by the artist:

"The social treatment of women is totally unequal... I want to express this (and ask), why is that so? My answer is, I think human beings are not civilised yet. They are still consuming meat. By eating meat, human beings become very brutal"[90]

The Flesh series was first shown in 2015 as part of a fund-raising exhibition at The Substation; the most expensive painting at the exhibition, which sold for $40,000, was a painting from the Flesh series.[91] The series was then shown at Flesh on Loop: Wong Keen's Solo Exhibition in 2018 before the large-scale exhibition Wong Keen: Flesh Matters in 2018 at Helutrans Art Space. The exhibition was co-organised by artcommune gallery and The Culture Story, and featured the mural-sized 305 x 610 cm painting The Aftermath (2017).[92][93][89] Wong Keen: Flesh Matters presented 50 works of art, including an installation, and worked as a formal and comprehensive introduction of Wong's Flesh series.[3][93]

Further reading

Wong Keen: After Thirty-Five Years in New York. Shenn's Fine Art (1996).

Lotus Figures: Recent Works by Wong Keen. Shenn's Fine Art (1997).

Wong Keen: A Singapore Abstract Expressionist. An Exhibition of Donated Works by Mr & Mrs Koh Seow Chuan. Singapore Art Museum (2007). ISBN 978-981-05-7762-9.

Expressions by Wong Keen. Galerie Belvédère (2007).

Encounters and Journeys: Singapore Artists—Chen Wen Hsi, Goh Beng Kwan, Wong Keen. Singapore Art Museum (2008). ISBN 978-981-05-9169-4.

Picture Writing: Sensuous Abstractions. artcommune gallery (2012). ISBN 978-981-07-3104-5.

Wong Keen. artcommune gallery (2013). ISBN 978-981-07-7394-6.

Second Nature: Paintings by Wong Keen. artcommune gallery (2014). ISBN 978-981-09-0849-2.

The Orbits of Colour. artcommune gallery (2016). ISBN 978-981-11-0314-8.

Wong Keen: A Creative Life Unfurled. artcommune gallery (2017). ISBN 978-981-11-3844-7.

Flesh Matters: Wong Keen. artcommune gallery and The Culture Story (2018). ISBN 978-981-11-7838-2.

References

- Ma, Peiyi (2017). Wong Keen: A Creative Life Unfurled. Singapore: artcommune gallery. pp. 4–68. ISBN 978-981-11-3844-7.

- Tan, Rebecca Hui Shan (22 May 2015). "Artist Wong Keen marches to his own drumbeat". The Straits Times. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- Yusof, Helmi (13 July 2018). "Flesh And Blood". The Business Times. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Chronology". Wong Keen: A Creative Life Unfurled. artcommune gallery. 2017. pp. 74–78. ISBN 978-981-11-3844-7.

- Kwok, Kian Chow; Ong, Zhen Min (2007). "Wong Keen: A Singapore Chapter to Abstract Expressionism". Wong Keen: A Singapore Abstract Expressionist. Singapore Art Museum. pp. 12–19. ISBN 978-981-05-7762-9.

- Lee, Chor Lin (2018). "Wong Keen in 2018". Flesh Matters: Wong Keen. artcommune gallery and The Culture Story. pp. 62–88. ISBN 978-981-11-7838-2.

- "青年画家王瑾驰誉美国艺坛". 星洲日报. 1 March 1965.

- Yeo, Mang Thong (2001). 新加坡第一代书画家翰墨集珍. 布莱德岭民众俱乐部华族传统艺术中心. ISBN 9789810462192.

- Ho, Sou Ping (2011). "Wong Keen: Calligraphic Interactions". MA Thesis. Singapore: LaSalle College of the Arts. pp. 29-31.

- Leong, Weng Kam (7 July 1997). "Like mother, like son, at calligraphy show". The Straits Times.

- Kwok, Kian Chow (May 2000). "Richard Walker, Colonial Art Education and visiting European artists before World War II". Postcolonial Web. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- "Wong Keen | Infopedia". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- Chow, Yian Ping (2019). "Chen Wen Hsi's Old House: A Dwelling for Hometown Reminiscence and New Creative Frontiers". Homecoming: Chen Wen Hsi Exhibition @ Kingsmead. artcommunegallery. pp. 24–35. ISBN 978-981-14-1143-4.

- Sabapathy, T. K. (2018). "The Nanyang Artists: Some General Remarks". Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History in Singapore, Malaysia & Southeast Asia 1973–2015. Singapore Art Museum. pp. 340–345. ISBN 9789811157639.

- "王瑾画展今日开幕". 星洲日报. 1 July 1961.

- "王瑾个人画展 今日延长一天". 星洲日报. 5 July 1961.

- "青年画家王瑾举行个展会". 星洲日报. 26 June 1961.

- "Wong Shows Art". Chinese-American Times. May 1963.

- "王瑾画展极受赞赏 连日购画者踊跃". 星洲日报. 4 July 1961.

- Hsu, Marco (1963). 马来亚艺术简史. 南洋出版有限公司. p. 134.

- Paul, Stella (October 2004). "Abstract Expressionism". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- Cummings, Paul (1973). "The Art Students League, Part II". Archives of American Art Journal. 13: 1–18.

- Farrell, Frank (7 September 1962). "A New Brush in Art World". New York World Telegram and Sun.

- Ma, Peiyi (2013). "The Visual Poetics of Wong Keen". Wong Keen. artcommune gallery. pp. 13–28. ISBN 978-981-07-7394-6.

- Ma, Peiyi (2013). "Early Life in Singapore and New York". Wong Keen. artcommune gallery. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-981-07-7394-6.

- Lee, Joanna. "Goh Beng Kwan". Infopedia. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- "将抽象表现主义画风带回纯真风格 王瑾展出画作备受好评". 世界日报. 28 May 1995.

- Farrell, Frank (10 Apr 1963). "Emmett Kelly". New York World Telegraph and Sun.

- "Chinese Artist". West Side News. 1963.

- "本邦青年画家王瑾 在纽约举行画展". 南洋商报. 10 Apr 1963.

- "Wong Keen to Give One-Man N.Y. Show". The Young China. 5 Apr 1963.

- "青年画家王瑾在纽约举行第二次个展简介". 南洋商报. 1 March 1965.

- "S'pore Artist Wins Praise in US". The Sunday Times. 21 March 1965.

- "Singapore Chinese Wins Art League Scholarship". New York Post. Jul 1965.

- "S'pore artist wins travel scholarship". The Straits Times. 21 June 1965.

- "中国青年画家王瑾获留学欧洲奖金". 中国时报. 1965.

- "留美青年画家 王瑾明晚返星". 星洲日报. 27 June 1965.

- Gore, F. J. P. (16 Mar 1966). "To Whom It May Concern: Wong Keen"

- "青年画家王瑾 在美举行个展". 星洲日报. 7 January 1967.

- "Wong Keen Exhibits at the League". Art Students League News. Dec 1966.

- Nicolin, Antony; Stroud, Peter (c. 1980s). "Introduction". Wong Keen.

- Moyer, Roy (1996). "After Thirty-Five Years in New York: An Introduction". Wong Keen: After Thirty-Five Years in New York. Shenn's Fine Art.

- Choy, Weng Yang (2013). "Themes and Variations: The Brilliance in Wong Keen's Inventive Art". Wong Keen. artcommune gallery. pp. 29–37. ISBN 978-981-07-7394-6.

- Ma, Peiyi (2016). The Orbits of Colour. artcommune gallery. ISBN 978-981-11-0314-8.

- Convergences: Chen Wen Hsi Centennial Exhibition. Singapore Art Museum. 2006. ISBN 9810551959.

- 黄, 向京 (28 Apr 2015). "30年画尽莲之变". 联合早报.

- Ma, Peiyi (2017). "The Eternal Resonance of Bada in Wong Keen's Art". Wong Keen: A Creative Life Unfurled. artcommune gallery. pp. 12–40. ISBN 978-981-11-3844-7.

- Ma, Peiyi (2017). "Artwork in Context: The Calligraphic Gesture in Nude with Black Stocking". Wong Keen: A Creative Life Unfurled. artcommune gallery. pp. 41–49. ISBN 978-981-11-3844-7.

- Wachted, Lilian (30 July 1971). "抽象派青年画家王瑾". 星洲日报.

- "王瑾画廊出手不凡 装裱配框画龙点睛". 华美日报. 24 January 1986.

- Grimmer, Mary (Mar–Apr 1992). "Serge Lemoyne: An Artist of Passions". Manhattan Arts.

- "Patrick O'Brien: Paintings, January 8 - January 29". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "李锡奇 Lee Shi-Chi: Recent Paintings, Oct 6 - Oct 23". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "Jenny Chen: Recent Works, June 11- July 2, 1993". Keen Gallery.

- "On the Edge, Recent Works: Ming Fay, November 5–26". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "Camilo Kerrigan: Recent Paintings". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "Dennis Hwang". Keen Gallery and Taiwan Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "Michiko Edamitsu: A Call of Soul - In quest of being behind being, June 3–24, 1995". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "Norman Barish: Paintings, 8–29 September 1992". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "花叫之燕:诗歌朗诵". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- "Prism View: A New Play by Joe Fox". Keen Gallery. Event ephemera.

- Wu, Hung (2010). Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents. Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 9780822349433.

- Lunde, Karl (1993). Red Star Over China: Tenuous Peace. Keen Gallery.

- 魏, 碧洲 (28 May 1995). "将抽象表现主义画风带回纯真风格 王瑾展出画作备受好评". 世界日报.

- "Biography". Flesh Matters: Wong Keen. artcommune gallery and The Culture Story. 2018. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-981-11-7838-2.

- "旅美画家王瑾油画展". 艺术家. 1989.

- 李, 玉玲 (6 May 1989). "王瑾个展 抽象女体的变形". 联合晚报.

- 张, 琼慧 (8 May 1989). "王瑾展抽象油画". 中时晚报.

- Richardt-Sylskar, Hope (7 May 1994). "Subtle and Poetic: Wong brings art to SSU Gallery". Independent.

- Leong, Weng Kam (3 August 1996). "Artist comes back with his report card after 35 years". The Straits Times.

- Munroe, Ben (27 July 1996). "A Duality of Influences". The Business Times.

- Sit, Y. F. (13 October 1995). "Seven Singapore artists to exhibit in New York". The Straits Times.

- 吴, 启基 (20 July 1996). "画中寻梦:旅美画家王瑾个展". 联合早报.

- Chia, Adeline (17 July 2008). "Home is where the art is". The Straits Times.

- Koh, Tommy (2007). "Foreword". Wong Keen: A Singapore Abstract Expressionist. Singapore Art Museum. p. 7. ISBN 978-981-05-7762-9.

- 吴, 启基 (8 March 2007). "许少全夫妇捐献63件王瑾画作落户美术馆". 联合早报.

- Chew, David (14 March 2007). "The artist laid bare: Wong Keen's latest exhibition of nudes displays his joy in experimentation". Today.

- 吴, 启基 (11 October 2007). "带着东南亚风味的光影色". 联合早报.

- Lim, Siew Kim. "Singapore Season". Infopedia. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- 吴, 启基 (20 July 1998). "非常"表现"的越南风景 旅美画家王瑾个展". 联合早报.

- Munroe, Ben (15 August 1997). "Something old, something new". The Business Times.

- Sian, E Jay (17 July 1998). "An artist's fascination with lotuses". The Business Times.

- Ma, Peiyi (2014). Second Nature: Paintings by Wong Keen. artcommune gallery. ISBN 978-981-09-0849-2.

- Picture Writing. artcommune gallery. 2012. ISBN 978-981-07-3104-5.

- Huang, Lijie (21 August 2012). "Writing with pictures". The Straits Times.

- Ma, Peiyi (2018). "The Road to Flesh, Part I: Genesis". Wong Keen: Flesh Matters. artcommune gallery and The Culture Story. pp. 14–26. ISBN 978-981-11-7838-2.

- Ma, Peiyi (2018). "The Road to Flesh, Part II: Departure and Synthesis". Wong Keen: Flesh Matters. artcommune galler and The Culture Story. pp. 27–60. ISBN 978-981-11-7838-2.

- Soutine/de Kooning: A Meeting of Minds. Paul Holberton Publishing. 2021. ISBN 9781911300885.

- 黄, 向京 (10 July 2018). "王瑾个展"肉意欲流" 生肉人体纠结的世界". 联合早报.

- Toh, Wen Li (4 July 2019). "Of hamburgers and humanity". The Straits Times.

- Tan, Rebecca Hui Shan (22 May 2015). "From nudes to raw meat". The Straits Times.

- Ma, Peiyi (2018). "The Language of Flesh: The Aftermath". Wong Keen: Flesh Matters. artcommune gallery and The Culture Story. pp. 98–101. ISBN 978-981-11-7838-2.

- Nanda, Akshita (17 July 2018). "Of flesh and meat". The Straits Times.