Women's suffrage in states of the United States

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

The campaign to establish women's right to vote in the states was conducted simultaneously with the campaign for an amendment to the United States Constitution that would establish that right fully in all states. That campaign succeeded with the ratification of Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

Background

The demand for women's suffrage began to gather strength in the 1840s, emerging from the broader movement for women's rights. The Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, generated a national debate by endorsing women's suffrage in 1848. By the time of the National Women's Rights Convention of 1851, the right to vote had become a central demand of the movement.[1]

The first national suffrage organizations were established in 1869 when two competing organizations were formed, each campaigning for suffrage at both the state and national levels. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was especially interested in national suffrage amendment. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone, tended to work more for suffrage at the state level.[2] They merged in 1890 as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[3]

Prospects for a national amendment looked dim at the turn of the century, and progress at the state level had slowed.[4] In the 1910s, however, the drive for a national amendment was revitalized, and the movement achieved a series of successes at the state level. The newly formed National Woman's Party (NWP), a militant organization led by Alice Paul, focused almost exclusively on the national amendment. The larger NAWSA, under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, also made the suffrage amendment its top priority.[5] In September 1918, President Wilson spoke before the Senate, asking for the suffrage amendment to be approved. The amendment was approved by Congress in 1919 and by the required number of states a year later.[6]

States and regions

West

On the whole, western states and territories were more favorable to women's suffrage than eastern states. It has been suggested that western areas, faced with a shortage of women on the frontier, "sweetened the deal" in order to make themselves more attractive to women so as to encourage female immigration or that they gave the vote as a reward to those women already there. Susan B. Anthony said that western men were more chivalrous than their eastern brethren.[7] In 1871 Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton toured several western states, with special attention to the territories of Wyoming and Utah where women already had equal suffrage. Their suffragist speeches were often ridiculed or denounced by the opinion makers: the politicians, ministers, and editors. Anthony returned to the West in 1877, 1895, and 1896. By the last trip, at age 76, Anthony's views had gained popularity and respect. Activists concentrated on the single issue of suffrage and went directly to the opinion makers to educate them and to persuade them to support the goal of suffrage.[8]

By 1920 when women got the vote nationwide, Wyoming women had already been voting for half a century.

Arizona

Arizona's early women's rights advocates were members of the WCTU.[9] Both Josephine Brawley Hughes and Frances Willard toured the state to recruit members in the mid 1880s.[9] The WCTU was successful at influencing the passage of several women's rights measures in the legislature.[10] During the 1891 constitutional convention for Arizona, women's suffrage was nearly added to the new constitution, but failed by three votes.[11] After the convention, Hughes and Mrs. E. D. Garlick formed the Arizona Suffrage Association.[12][11] A bill to allow women to vote in school board elections passed in 1897.[13] Women's suffrage bills went to the territorial legislature in 1899 and in 1901, but did not pass.[14][15] After 1905, the women's suffrage movement stalled in Arizona for several years.[16]

As it looked likely for Arizona to become a state, NAWSA started to campaign in the territory in 1909, sending field worker, Laura Clay.[17][16] Clay and Frances Munds lobbied the territorial legislature but women's suffrage bills failed despite their efforts.[17] Laura Gregg came to Arizona in 1910 and organized suffrage groups and campaigned.[18] Gregg met with thousands of women and organized Mormon women in the state.[19] Activists formed the Arizona Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) with Munds as president, and launched a campaign to win the vote.[20] During the constitutional convention of 1910, suffragists packed the gallery and Gregg brought a petition of 3,000 signatures in support of equal suffrage.[21] Their efforts failed due to fears that if the Arizona Constitution contained women's suffrage, they would not be admitted as a state.[22] When Arizona became a state in February 1912, suffragists went into action to get a women's suffrage referendum on the ballot.[23] Activists crossed the state and received enough signatures to get suffrage on the ballot.[24][25] They translated suffrage materials into Spanish.[26] Suffragists in the state reached out to progressive organizations for endorsements, winning the support of influential political and civic leaders, and getting help from NAWSA for speakers and funds.[27][28] AESA sent delegations to the Republican and Democratic state conventions to argue for their support.[29] The tactics worked and the men voted for woman suffrage in the general election held on 5 November 1912.[30][31]

Women first registered to vote in 1913 and participated in the state primary elections in 1914.[32] Arizona ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 12, 1920.[33][34] Native Americans in Arizona were excluded from voting due to their citizenship status.[35] In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act made all Native Americans United States citizens.[35] However, there was disagreement about whether Native Americans in Arizona could now vote.[36] In 1928, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans living on reservations could not vote.[37] In 1948, the court reversed that decision.[38] Nevertheless, literacy tests continued to block Native Americans from voting.[39] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 helped enfranchise more Native Americans.[39]

California

California's voters granted women's suffrage in 1911, when they adopted Proposition 4. Hundreds of women and men were involved in the California suffrage campaign. Clara Elizabeth Chan Lee was the first Chinese American woman voter in the United States.[40] She registered to vote on November 8, 1911 in California.[40]

Colorado

The former territorial governor, John Evans, promoted women's suffrage in the territorial legislature in 1868.[41] Women's suffrage was proposed again in the legislature by Governor Edward M. McCook in 1870.[41] A women's suffrage group, the Territorial Woman Suffrage Society was formed in 1876 and went on to address the state constitutional convention.[42] While women did not get equal suffrage from the new constitution, they were granted the right to vote in school board elections.[43] A full suffrage referendum was passed and would be voted on October 2, 1877.[44][45] Despite the efforts of suffragists from around the country, the referendum was defeated.[45] Activists continued to fight for equal suffrage, forming new groups,[46] lobbying the legislature,[47] writing about suffrage,[44][48] and urging women to exercise their right to vote in school elections.[49]

The Colorado General Assembly passed another referendum for 1893.[50] Suffrage groups in the state started out with only $25 to fund their campaigns.[51] NAWSA sent funds and organizers to Colorado.[51][52][53] Journalist, Minnie Reynolds convinced around 75% of newspapers in the state to support the suffrage effort.[54] When the referendum passed on November 7, 1893, it made Colorado second state to give women suffrage and the first state where the men voted to give women the right to vote.[55] After women gained equal suffrage, they ran for office and supported reform efforts in the state.[56][57] Activists from Colorado continued to support women's suffrage efforts in other states and some, like Caroline Spencer, joined the Congressional Union.[58][59] Colorado ratified the 19th Amendment on December 15, 1919.[60] Native American women who lived on reservations, however, were unable to vote in Colorado until 1970.[61]

Idaho

Idaho approved a constitutional amendment in 1896 with a statewide vote giving women the right to vote. Idaho was one of the first states to allow the amendment.

Montana

Montana's men voted to end the discrimination against women in 1914, and together they proceeded to elect the first woman to the United States Congress in 1916, Jeannette Rankin.

Nevada

New Mexico

New Mexico allowed women to vote in school board elections when the state constitution was written and after it became a state.[62] After this, suffragists in New Mexico continued to fight for a federal suffrage amendment.[63]

Oregon

One after another, western states granted the right of voting to their women citizens, the only opposition being presented by the liquor interests and the machine politicians. In Oregon, Abigail Scott Duniway (1834–1915) was the long-time leader, supporting the cause through speeches and her weekly newspaper The New Northwest, (1871–1887).[64] Suffrage was won in 1912 by activists who used the new initiative processes.

Utah

The prevalence of Mormonism in Utah made the fight for women's suffrage there unique. In 1869 the Utah Territory, controlled by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), gave women the right to vote.[65] Seraph Young, the niece of Brigham Young, was the first woman to vote under a women's equal suffrage law in the United States, due to a municipal election held on February 14, 1869 (Wyoming had recognized women's right to vote earlier that year, but had not yet held an election).[66] However, in 1887, Congress disenfranchised Utah women with the Edmunds–Tucker Act, which was designed to weaken the Mormons politically and punish them for polygamy.[67] At the same time, however, certain activists, particularly Presbyterians and other Protestants convinced that Mormonism was a non-Christian cult that grossly mistreated women, promoted women's suffrage in Utah as an experiment, and as a way to eliminate polygamy.[68] The LDS Church officially ended its endorsement of polygamy in 1890 and in 1895 Utah adopted a constitution restoring the right of woman suffrage. Congress admitted Utah as a state with that constitution in 1896.[69]

Washington

In 1854, Washington became one of the first territories to attempt granting voting rights to women; the legislative measure was defeated by only one vote. In 1871, the Washington Women's Suffrage Association was formed, largely attributable to a crusade through Washington and Oregon led by Susan B. Anthony and Abigail Scott Duniway. The late nineteenth century saw a seesaw of bills passed by the Territorial Legislature and subsequently overturned by the Territorial Supreme Court, as the competing interests of the suffrage movement and the liquor industry (which was being damaged by the women's vote) battled over the issue. The first successful bill passed in 1883 (overturned in 1887), the next in 1888 (overturned the same year). The women's suffrage movement next hoped to secure the right to vote via voter referendum, first in 1889 (the same year Washington achieved statehood), and again in 1898, but both referendum bids were unsuccessful. A constitutional amendment finally granted women the right to vote in 1910.[70][71][72]

Wyoming

On December 10, 1869, Territorial Governor John Allen Campbell signed an act of the Wyoming Territorial Legislature granting women the right to vote, the first U.S. state or territory to grant suffrage to women.[73] On September 6, 1870, Louisa Ann Swain of Laramie, Wyoming became the first woman to cast a vote in a general election.[74][75] In 1890, Wyoming, with a Republican governor and Democratic legislature, insisted it would not accept statehood without keeping women's suffrage. When the U.S. Congress demanded Wyoming rescind the right of women to vote as a condition of statehood, the Wyoming legislature fired back in a telegram: “We will remain out of the Union one hundred years rather than come in without the women.” Congress gave in, and thus, in becoming the 44th state, Wyoming became the first U.S. state in which women could vote.[76]

Connecticut

The women's suffrage movement in Connecticut was pioneered by Frances Ellen Burr, a lecturer and writer who led a petition drive for suffrage in the 1860s. She had been part of the women's movement for some time, having attended the National Women's Rights Convention in Cleveland in 1853. Through her efforts, a women's suffrage bill was introduced into the state House of Representatives in 1867. It was defeated by a vote of 111 to 93.[77]

The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) was formed at the state's first women's suffrage convention at the Robert's Opera House in Hartford on October 28–29, 1869. The convention was organized by a group that included Burr, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Catharine Beecher, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The meeting was addressed by a number of activists, including Henry Ward Beecher, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Julia Ward Howe and William Lloyd Garrison.[78] The convention, with its heavy involvement by the influential Beecher family, did not receive the hostile reception that similar conventions had received in other places. The local press reported on the convention in a respectful way, and Stanton, Howe and Anthony were entertained by the governor and his wife at the governor's mansion.[79]

At the time of the convention, the national women's movement was in the process of splitting. One wing, associated with Stanton and Anthony, had formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). The other, associated with Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, had formed the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) and would soon form the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Isabella Beecher Hooker invited both parties to the Hartford convention and tried to heal the breach between them, but was unsuccessful.[80] The Beecher family generally opposed Anthony's and Stanton's NWSA (Isabella's brother, Henry Ward Beecher, was the first president of the more moderate AWSA[81]). Isabella, however, was friendly with Anthony and Stanton and served as NWSA's vice president for Connecticut.[82]

Isabella Beecher Hooker was the leading force in the CWSA and led the suffrage movement in that state for the rest of the century.[83][77] The New England Woman Suffrage Association organized affiliated state suffrage societies in most New England states except for Connecticut.[84] The CWSA recorded a membership of 288 in 1871.[83]

In the 1870s, sisters Julia and Abby Smith, sometimes known as the "Maids of Glastonbury," engaged in a "no taxation without representation" protest. They refused to pay their local taxes because women were not allowed to vote on tax issues. The town seized their property to pay the taxes.[85]

The movement won a few victories during this period. Married women won the right to control their own property in 1877. Women won the right to vote for school officials in 1893 and on library issues in 1909. The slow pace of progress was discouraging, however, and by 1906, the CWSA was down to 50 members.[86]

In 1909, at time of a nationwide upsurge in the women's suffrage movement, Katharine Houghton Hepburn (mother of Academy Award winning actress Katharine Hepburn) co-founded the Hartford Equal Suffrage League. In 1910, that organization merged with the CWSA, and Hepburn became its president.[87] Imbued with new energy, the CWSA sponsored a month-long automobile tour in 1911 that established a number of new local chapters. In 1914, it was the main organizer of the state's first suffrage parade, with 2000 participants. By 1917, the organization had 32,000 members.[86]

With Hepburn's support, a branch of a suffrage organization called the Congressional Union was formed in Connecticut in 1915. By 1917, it had become the state branch of the National Woman's Party (NWP), a rival to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) with which the CWSA was affiliated. Adopting the militant tactics of the NWP, fourteen Connecticut suffragists were arrested between 1917 and 1919 in Washington, D.C. for picketing the White House.[86] Distressed by the NAWSA's reluctance to condemn the harsh treatment of the protesters, Hepburn resigned her post as president of the CWSA in 1917 and joined the NWP, soon becoming a member of its national executive committee. She did not resign her CWSA membership, however, and continued to attend its board meetings.[88]

Such cooperation across rival organizational lines was not uncommon in the Connecticut women's movement. In many other states and at the national level, by contrast, the NWP and the much larger NAWSA tended to be bitter and uncooperative rivals. A representative statement of Connecticut approach was expressed Ruth McIntire Dadourian, the CWSA executive secretary, who said, "I felt that the Woman's Party was really the spearhead and then we could follow through. The more outrageous they were, the better off we were."[89]

Controlled by conservative Henry Roraback's Republican Party machine, Connecticut resisted the rapidly increasing pressure across the country to support the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which would prohibit the denial of the right to vote on the basis of sex. The state legislature, which finally met in a special session called specifically to consider the amendment, ratified it in September 1920, a month after it had already become the law of the land because a sufficient number of other states had ratified it.[86] Its work done, the CWSA dissolved in 1921.[78]

Maine

Women's suffrage work started in the mid 1850s in Maine. Several prominent suffragists spoke in Maine during that time period and in 1857 a women's rights lecture series was established in Ellsworth.[90][91] The Ellsworth lecture series was started by Ann F. Jarvis Greely, her sister Sarah Jarvis, and Charlotte Hill.[92] The lectures later led to activism, with women in Maine creating women's suffrage petitions which were sent to the state legislature.[93][94] By the late 1860s the Snow sisters, Lavina, Lucy, and Elvira in Rockland started a women's suffrage club.[95] During the 1870s, Margaret W. Campbell traveled throughout Maine and spoke on women's suffrage.[96] The writer, John Neal, called for the creation of a women's suffrage organization and a convention.[97] A convention was held in Augusta in 1873 which featured prominent suffragists and oversaw the creation of the Maine Women's Suffrage Association (MWSA).[98][99][100] During the later half of the 1870s, many Maine suffragists were involved in the WCTU.[101] Cordelia A. Quinby continued suffrage work during the slow period that lasted until around 1885.[102]

During a convention that was jointly held by the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) the MWSA was revived and a Unitarian pastor, Henry Blanchard, became the next president.[103][100] Petitions on women's suffrage to the state lawmakers resumed.[104] In 1887, the state legislature considered a women's suffrage amendment, but it did not receive enough votes to pass.[105] Several other women's suffrage bills were considered over the next few years, but were unsuccessful.[106][105] In 1891 Hannah Johnston Bailey, who was active in the WCTU, became president of the MWSA.[100][107] In the next few years, the MWSA and the WCTU campaigned for women's suffrage and sent petitions to the state legislature.[108][105] While activists were unsuccessful in getting women's suffrage passed, they did secure women's rights legislation.[109]

During the next few decades, MWSA continued to steadily work towards women's suffrage and allied the group with NAWSA.[110] Groups such as the Maine Federation of Labor publicly endorsed women's suffrage in Maine in 1906.[111] The Socialist Party also came out in favor of women's right to vote and MWSA president, Helen N. Bates publicly thanked them for their stance in 1912.[112] In 1913, the Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League was formed and the next year, the Men's Equal Rights League of Maine was organized.[111][113] In 1915, Florence Brooks Whitehouse brought the Congressional Union to Maine.[113]

By 1916, suffragists in Maine felt that it was time to heavily campaign for a women's suffrage amendment.[114] They held a suffrage school in January 1917 in preparation for the campaign.[114] When the bill went to the state legislature, there were more than 1,000 women watching the proceedings.[112] The bill passed and would go to a referendum on September 1917.[115] Campaign headquarters were set up in Bangor.[112] Suffragist, Deborah Knox Livingston, traveled more than 200,000 miles throughout the state campaigning.[116] More than 500 suffrage meetings took place during the last three months of the campaign.[116] Despite all the hard work, the voters were against women's suffrage and the amendment failed.[117]

In February 1919, a women's suffrage law to vote for presidential electors passed the state and would go out for a voter referendum on September 13, 1920.[118] In November of 1919, a special legislative session was called and Maine ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on November 5.[119]

New Jersey

New Jersey, on confederation of the United States following the Revolutionary War, placed only one restriction on the general suffrage—the possession of at least £50 (about $10,100 adjusted for inflation) in cash or property.[120][121] In 1790, the law was revised to include women specifically, and in 1797 the election laws referred to a voter as "he or she".[122] Female voters became so objectionable to professional politicians, that in 1807 the law was revised to exclude them. Later, when New Jersey rewrote its constitution, the 1844 constitution limited a guaranteed right to vote to men. By 1947, all state constitutional provisions that barred women from voting had been rendered ineffective by the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920. The updated constitution of 1947, reflecting this, once again included women as eligible voters—as they had been in New Jersey in 1776.

New York

Suffragists, knowing that women's suffrage could not succeed without support, put their hope in the Equal Rights Association and pushed for a campaign for universal suffrage. From April until November 1867, women furiously campaigned, distributing thousands of pamphlets and speaking in numerous locations for the cause. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton focused their attentions on New York, while Stone and Blackwell headed to Kansas, where the November election would be taking place.[123]

During the New York Constitutional Convention, held on June 4, 1867, Horace Greeley, the chairman of the committee on Suffrage and an ardent supporter of women's suffrage over the previous 20 years, betrayed the women's movement and submitted a report in favor of removal of property qualification for free black men, but against women's suffrage. New York legislators supported the report by a vote of 125 to 19.[124]

Harriot Stanton Blatch, the daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, focused on New York where she succeeded in mobilizing many working-class women, even as she continued to collaborate with prominent society women. She could organize militant street protests while still working expertly in backroom politics to neutralize the opposition of Sharp Hall politicians who feared the women would vote for prohibition.[125] New York finally joined the procession in 1917 after Tammany Hall ended its opposition.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania was a center of women’s rights activism and home to many notable activists, including Lucretia Mott and the Grimke Sisters (Sarah Moore Grimke and Angelina Emily Grimke). In 1854, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society held one of the nation's early women’s rights conventions. In 1969, Philadelphia was home to the state’s first organized gathering of suffragists.

On October 10, 1871, Carrie S. Burnham tried to vote in a local election.[126] When polling officials rejected her ballot, she took her case to court. It rose to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, but was unsuccessful. She argued before the court that she had the right to vote on the grounds that she met the legal definition of a “freeman” and a citizen of the United States; her argument was published in a pamphlet[127] that same year.

Amending the state constitution to include woman suffrage required a resolution to pass through two sessions of the state legislature and then ratification by the state’s voters in the next election.[128] Groups began lobbying for an amendment in 1911, and it passed the legislature in 1913. The state’s first suffrage march was held in Perry Square in Erie in 1913, organized by Augusta Fleming and Helen Semple.[129] It was followed by others throughout the state, including a protest and march in Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia in 1914.

In 1915, as the measure for state-level woman suffrage was on the ballot in state elections, Katharine Wentworth Ruschenberger and the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association funded the creation of the Justice Bell, a replica of the Liberty Bell whose clapper was secured so that it could not ring out until women won the right to vote. Jennie Bradley Roessing, President of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association, and Vice President Hannah J. Patterson, drove the Justice Bell to campaign events in all 67 of the state's counties,[130][129] but the referendum was defeated in 1915.

Pennsylvania’s women did not get the right to vote until passage of the federal amendment, which was ratified by the Pennsylvania legislature on June 24, 1919, making Pennsylvania the 7th state to ratify it.

Rhode Island

Midwest

Norwegian American women, based in the rural upper Midwest, felt that the progressive politics of Norway, which included women's rights, provided a strong foundation for their demands for political equality and inclusion in the U.S. They told their kinswomen they had a cultural duty to promote women's rights, especially through the Scandinavian Woman's Suffrage Association.[131]

Illinois

An early Illinois women's suffrage organization was created by Susan Hoxie Richardson in 1855 in Earlville, Illinois.[132] Women in Illinois helped the war effort during the Civil War.[132] Through her war work, Mary Livermore became convinced that women needed to vote so that they could enact political reform.[132] Livermore organized the first suffrage convention in the state, holding it in Chicago in 1869.[133] In the 1870s, suffragists advocated for changing laws to allow women to vote.[134] During the 1880s and 1890s there was more organizing and efforts to introduce women's suffrage in the state legislature.[135][136][137] In 1891, a school suffrage bill passed.[137] That same year, Ellen A. Martin exploited a loophole in the city charter of Lombard, Illinois which allowed her and other women to legally cast ballots.[138][139]

In the 1900s, Illinois suffragists continued to educate, raise awareness, and conduct outreach throughout the state.[140] By the 1910s, women had gained a large amount of political savvy and developed political networks.[141] Grace Wilbur Trout, a leader in the movement organized car rallies and other publicity-raising events.[142][143] She made sure that a local organization was started in every Senate district in the state.[144]

The first Black suffrage organization in the state, the Alpha Suffrage Club was founded in 1913.[145] Trout, other Illinois suffragists, and Ida B. Wells from the Alpha Suffrage Club, went to the Woman Suffrage Procession in March.[146][147] While some suffragists tried to keep Wells from marching with the other suffragists, Wells refused and managed to march in the parade as an integrated unit.[148]

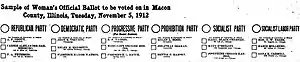

In May 1913, a women's suffrage bill was introduced and passed the state Senate.[149] After passing the State Senate, the bill was brought up for a vote in the House on June 11, 1913.[143] Watching the door to the House chambers, Trout urged members in favor not to leave before the vote, while also trying to prevent "anti" lobbyists from illegally being allowed onto the House floor.[143] The bill passed with six votes to spare, 83 to 58.[143][150] On June 26, 1913, Illinois Governor Edward F. Dunne signed the bill.[151]

Women in Illinois could now vote for presidential electors and for all local offices not specifically named in the Illinois Constitution.[143] But by virtue of this law, Illinois had become the first state east of the Mississippi River to grant women the right to vote for president.[143] It was important to show anti-suffragists that women really did want to vote.[152] Women's clubs, including the Alpha Suffrage Club, worked together to get women to vote.[153] More than 200,000 women were registered to vote in Chicago alone.[152][154]

When the Nineteenth Amendment was going out to the states for ratification, some states wanted to become the first to ratify.[155] On June 10, 1919, Illinois became the first state to the East of the Mississippi to ratify the amendment.[155] It was the seventh state to ratify.[156]

Iowa

Kansas

In March 1867, the Kansas legislature decided to include two suffrage referendums in that year's November election. If approved by the voters, one would enfranchise African Americans and the other would enfranchise women. The proposal for the referendum on women's suffrage, the first in the U.S., originated with state senator Sam Wood, leader of a rebel faction of the state Republican Party. Wood had moved to Kansas to oppose the extension of slavery into that state.[157]

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) actively supported both referendums. The AERA, which advocated suffrage for both women and blacks, had been formed in 1866 by abolitionists and women's rights activists. Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell launched the AERA campaign in Kansas. In April they assisted with the formation of a state organization called the Impartial Suffrage Association, which was led by Charles L. Robinson, a former governor who was Stone's brother's brother-in-law, and Sam Wood.[158] Olympia Brown arrived in Kansas on July 1 to relieve Stone and Blackwell as leader of the AERA campaign, handling that task almost single-handedly until Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton arrived in September. The AERA could not afford to send more activists because money that had expected to support their campaign had been blocked by Wendell Phillips, a leading abolitionist. Although he supported women's rights, Phillips believed that suffrage for African American men was the key issue of the day, and he objected to mixing the issues of suffrage for blacks and women.[159]

The AERA had hoped for assistance from the Kansas Republican Party. The Republicans instead decided to support suffrage for black men only and formed an "Anti Female Suffrage Committee" to oppose those who were campaigning for women's suffrage.[160][161] By the end of summer the AERA campaign had almost collapsed under the weight of Republican hostility, and its finances were exhausted.[162]

Anthony and Stanton created a storm of controversy by accepting help during the last two and a half weeks of the campaign from George Francis Train, a Democrat, a wealthy businessman and a flamboyant speaker who supported women's rights. Train, however, also openly disparaged the integrity and intelligence of African Americans, supporting women's suffrage partly in the belief that the votes of women would help contain the political power of blacks.[163] The usual procedure was for Anthony to speak first, declaring that the ability to vote rightfully belonged to both women and blacks. Train would speak next, declaring that it would be an outrage for blacks to vote but not women also.[164] The willingness of Anthony and Stanton to work with Train alienated many AERA members. This was due partly to Train's attitude toward blacks and partly to his harsh attacks on the Republican Party: he made no secret of his desire to blemish its progressive image and create splits within it. Many reformers were loyal to the national Republican Party, which had provided political leadership for the elimination of slavery and was still in the difficult process of consolidating that victory.[165]

Suffrage for women was defeated in the November election by 19,857 votes to 9,070; suffrage for blacks was defeated 19,421 to 10,483.[166] The tension created by the failed AERA campaign in Kansas contributed to the growing split in the women's suffrage movement.[167]

In 1887, suffrage for women was secured for municipal elections. That year, in Argonia, Susanna Salter became the first woman mayor elected in the United States.[168]

A referendum for full suffrage was defeated in 1894, despite the rural syndication of the pro-suffragist The Farmer's Wife newspaper and a better-concerted, but fractured campaign. A third referendum campaign in 1911-1912 gained even greater support, with supporters delivering 100 petitions with 25,000 signatures to Topeka. The fact that Kansas had already banned saloons since 1880 had severely weakened the anti-suffrage opposition by eliminating their traditional voter base of saloon patrons. The 1911-1912 pro-suffrage proposers also conducted a less-perceivably-antagonistic campaign among male voters. The pro-suffrage side finally secured a women's suffrage amendment, and Kansas became the eighth state to allow for full suffrage for women.[169] Suffrage was passed in Kansas largely spurred by a speech, the first Kansas state resolution endorsing woman's suffrage, made by Judge Granville Pearl Aikman at a Republican state convention.[170] Aikman would go on to appoint the nation's first female bailiff[171] and empanel Kansas' first (the nation's second after San Francisco) all-female jury.[172]

Missouri

Suffragists in Missouri can trace their roots to the Ladies Union Aid Society of St. Louis (LUAS).[173] Members of this group went on to form the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri (WSAM) in 1867.[174][175] The group began a petition campaign which was favorably received by members of the Missouri General Assembly, but was eventually unsuccessful.[176][177] In 1869, the first state women's suffrage convention was held.[178][179] Virginia Minor discussed the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment provided women the right to vote.[180][181] In the early 1870s many women inspired by Minor, both Black and white, performed civil disobedience by attempting to vote.[181][182] Minor was denied the right to vote and appealed her case all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States where it was heard as Minor v. Happersett.[181] The court ruled that citizens are not guaranteed the right to vote and ended any hope that suffragists had for getting women's suffrage through judicial measures.[180]

In 1910, the Equal Suffrage League (ESL) was formed with Florence Wyman Richardson as president.[183] Three other state clubs merged to form the Missouri Equal Suffrage Association (MESA).[184] During the Woman Suffrage Procession, Missouri was well represented and had an all-female marching band that calmed the rowdy crowd.[185][186] During the rest of 1913 and 1914, suffragists held conventions and parade.[187][188][189] During the 1916 Democratic National Convention, suffragists held a "walkless, talkless parade."[190][191][192] In 1919, women earned the right to vote for presidential electors.[193][194] The Nineteenth Amendment was ratified by Missouri on July 2, 1919.[195] The League of Women Voters of Missouri was formed in October 1919.[196]

North Dakota

When North Dakota and South Dakota were the same territory, they shared the same history.[197] Before their entrance as states, the territories granted women the right to vote in school elections in 1897, with further addendums in 1883.[198][199][200]

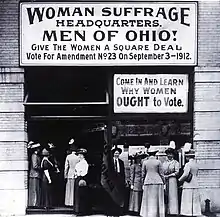

Ohio

Ohio women's suffrage work was kicked off by the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.[201] Elizabeth Bisbee from Columbus was inspired by the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments to start a women's suffrage newspaper that year.[201] The first Ohio Women's Rights Convention took place in Salem, Ohio in April 1850 and was presided over by Betsy Mix Cowles.[202][203] It was the first women's rights conference held outside of New York and only women were allowed to speak or vote during the convention.[202][204] One attendee of the convention, John Allen Campbell, later went onto to grant women equal suffrage in Wyoming.[204] Frances Dana Barker Gage was the president of the next women's rights convention in Ohio, held in Akron in 1851.[202][205] One of the speakers was Sojourner Truth who influenced Cleveland attendee, Caroline Severance.[206] At the conference, thousands of signatures were collected in favor of women's suffrage and later delivered to the 1850 Ohio Constitutional Convention.[207][201] However, both women and African-Americans continued to be disenfranchised.[208] At the Ohio Women's Rights Convention held in Massillon, Ohio in 1852, the Ohio Woman's Rights Association (OWRA) was formed.[201] Severance served as the first president.[209] The fourth National Women's Rights Convention was held in Cleveland on October 6, 1853 and the sixth was held in Cincinnati in 1855.[210] In 1869, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was formed in Cleveland.[211][212] Toledo, Ohio and Dayton, Ohio also formed local suffrage organizations in 1869.[213][214] In the 1870s, women in South Newbury, Ohio attempted to vote, but were unsuccessful in having their ballots counted.[212] During the 1873 Ohio Constitutional Convention suffragists sent petitions and a committee to influence the delegates.[215] However, women's suffrage did not make the final cut.[216] The Ohio Woman Suffrage Association (OWSA) was founded in Painesville, Ohio in 1885.[217] In 1888 Louise Southworth began compiling a database of people in Ohio who supported women's suffrage.[218]

By 1894 women gained the right to vote in school board elections, but not on infrastructure bonds in schools.[219] Women voted in school elections for the first time in 1895.[220] Harriet Taylor Upton became president of OWSA in 1899.[213] She also served as treasurer for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[221] Upton began to organize women around Ohio and doubled participation of activists in the movement over the course of 1900.[222] In 1903, NAWSA moved their national headquarters to Warren, Ohio.[223]

During 1912 the next constitutional convention in Ohio was held and women in the state were already energized from California's women's suffrage win.[224][213] During the convention, a women's suffrage referendum was passed.[225] Activists campaigned heavily both for and against the women's suffrage referendum.[214][223][226][217][221] Despite the hard work of suffragists, the referendum failed, with most counties opposing women's suffrage.[214][225] After the loss, Ohio suffragists regrouped and reorganized. Several new suffrage groups were formed and Ohio women worked in 1914 to get another women's suffrage referendum on the next ballot.[227] Again there was another large campaign, but the referendum failed.[228][229][214]

After the 1914 defeat, Ohio suffragists turned to pursuing municipal election suffrage for women.[223] On June 6, 1916 women East Cleveland, Ohio won the right to vote in city elections.[230][214] name=":133"/> In 1917 women in Lakewood, Ohio and Columbus, Ohio won municipal suffrage rights.[221] Briefly, Ohio women earned the right to vote for presidential electors in 1917, but it was repealed after a narrowly decided voter referendum.[231][232][212] On June 16, 1919 Ohio ratified the Nineteenth Amendment, becoming the fifth state to ratify.[202][213]

South Dakota

Women in South Dakota had a shared history with North Dakota until 1889, during which they did get the right to vote in school elections starting in 1887.[198] Activists in the state worked steadily over the years to build a case for women's suffrage. However, they did not pass a full equal suffrage amendment until 1918.[233] South Dakota passed the Nineteenth Amendment on December 4, 1919.[234]

Wisconsin

Women's suffrage, and other progressive issues were discussed during the first state constitutional convention in Wisconsin in 1846.[235] Early newspapers in Wisconsin supported women's suffrage.[236] Temperance advocates also toured Wisconsin and discussed the importance of the women's vote.[236][237] The first women's suffrage conference in Wisconsin was held in Janesville in 1867.[238] Later, the Woman Suffrage Association of Wisconsin (WSAW) was formed in order to lobby the state legislature on two women's suffrage amendment bills that were unsuccessful.[239][237] A new organization, the Wisconsin Woman Suffrage Association (WWSA), was organized at the 1869 Milwaukee suffrage convention.[240][241] Several chapters of WWSA were formed around the state by 1870.[242] Members of WWSA worked to spread the word about women's suffrage over the next decade.[243] In 1884 a women's suffrage bill was passed, allowing women to vote for school-related issues.[244] The bill had to pass a second time in 1885, which it did with help from Alura Collins Hollister.[245] Then it went out for a voter referendum in 1886 which passed.[245] The vague phrasing of the law and voter suppression efforts taking place during the first time women voted in 1887 led to problems.[246][247][248] Olympia Brown took the issue to court and it went as far as the Supreme Court of the United States.[249][250] It was decided that women in Wisconsin could only vote on school-related issues if a separate ballot and separate ballot boxes were created for women to use.[251] This eventually happened and women were able to vote for school-related issues again starting on April 1, 1902.[252][251][253]

The Wisconsin legislature passed another women's suffrage referendum in 1911.[251] Multiple suffrage groups campaigned heavily for the referendum to take place on November 4, 1912.[254] The efforts did not succeed and the referendum was voted down.[255] Suffragists continued to educate and organize after the defeat.[256] By 1916, most suffragists in Wisconsin had signed onto the "Winning Plan" supported by NAWSA and Catt.[257] Others became involved with the more militant NWP.[258][259][260] As the federal amendment passed, Wisconsin fought to become the first state to ratify.[261] Wisconsin ratified the Nineteenth Amendment one hour after Illinois.[262] However, Wisconsin was the first to turn in their ratification paperwork at the State Department.[263]

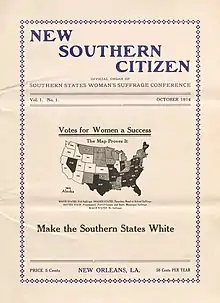

South

Southern suffragists are often left out of mainstream histories of the movement. Their work was imbued with the cultural assumptions of their day.[264] Many suffragists in the South—both white and black—were predominantly clubwomen, highly educated, and often from more elite families. Black women suffragists worked within their local clubs and later with the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs; some also became individual members of a suffrage association when their clubs were denied membership. Many black women educators, active in their teacher associations, would also speak out for voting rights, either for their men who were granted voting rights with the 15th Amendment and sometimes specifying voting rights for black women.[265] White middle-class women of the South who fought for voting rights were skilled in organizational efforts utilized in memorializing the Lost Cause[266] through a Ladies' Memorial Association or the United Daughters of the Confederacy.[267] In 1906 twelve delegates from states throughout the South came together in Memphis to form the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference. Laura Clay was elected president. This group broke from the NAWSA, which had turned away from its "Southern Strategy" efforts and worked instead to win suffrage at the state and local levels rather than with a federal amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Alabama

Early women's suffrage work in Alabama began in the 1860s when Priscilla Holmes Drake moved to the state.[268] Drake and her husband were the face of the women's suffrage movement in the state for many years.[268] Many women involved in the temperance movement began to become involved with women's suffrage.[268][269] In 1890s, several women's suffrage groups were organized with the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO) formed in 1893.[270][268] Emera Frances Griffin was a suffrage leader during the 1890s.[268] Griffin also testified at the state constitutional convention in 1901 and lobbied state legislators on women's suffrage.[271][272] However, after 1901, there was a long hiatus of women's suffrage efforts.[273]

In the 1910s several women's suffrage groups were formed again, starting in Selma, Alabama with Mary Partridge.[274][275] A Birmingham, Alabama suffrage league was started by Pattie Ruffner Jacobs in 1911.[276][274] Another state group, the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association (AESA) was formed and affiliated with NAWSA.[277] Both Jacobs and Partridge were involved.[278] AESA started holding state conventions in 1913.[278] AESA was able to influence some bills in the state legislature.[279] In 1915, a women's suffrage bill was introduced, but does not pass.[280][281]

By 1917, suffragists in Alabama began to feel that their best chance to get the vote was to support the federal suffrage amendment.[282][283] In June 1919, AESA started a campaign to promote and support the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.[284] Suffragists from around the state came to Montgomery, Alabama to lobby the legislature.[285] However, though the state legislature considered ratifying the amendment, it was eventually rejected on July 17 by the state Senate and rejected by the House in August.[285] In April 1920, AESA dissolved and formed the LWV of Alabama.[286] Alabama ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on September 8, 1953.[287]

Arkansas

Early women's suffrage activism came from men in Arkansas. Miles Ledford Langley advocated for women's suffrage at the 1869 state constitutional convention.[288] Educator, James Mitchell, wanted to see women's suffrage happen so that his daughters could have equal rights.[289] In 1881, Lizzie Dorman Fyler started a state women's suffrage club that lasted until 1885.[290] Clara McDiarmid started another women's suffrage group in 1888.[291][290] The Woman's Chronicle, which was edited by women and for women also started publication in 1888.[292] Several women's suffrage measures were considered by the Arkansas General Assembly over the next few decades but were unsuccessful.[293]

In the 1910s, women's suffrage efforts gained momentum in the state. Socialist women, such as Freda Ameringer were involved in suffrage work.[294] Several women's suffrage groups were created in during the decade, including the Political Equality League (PEL) and the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).[295][296] Suffragist, Florence Brown Cotnam became the first woman to speak on the floor of the General Assembly in 1915 when she testified about a women's suffrage amendment being considered.[297][298] While that measure did not pass, Cotnam was able to persuade the Governor to call for a special legislative session in 1917.[299] During this session, a bill to allow women to vote in primary elections was passed.[300] Arkansas became the first state that did not have equal suffrage to pass a primary election law for women.[301] After the passage of the primary election law, women worked to reorganize, make sure that women paid poll taxes, and educate voters.[302][301][303] The first time women could vote was in May 1918 during the primary elections and between 40,000 and 50,000 white women turned out to vote.[304] African-American women were barred from voting in the primaries.[305] Arkansas ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on July 28, 1919, becoming the twelfth state to ratify the amendment.[306][307]

Delaware

At a women's rights convention in 1869, the Delaware Suffrage Association was formed.[308] Mary Ann Sorden Stuart, a women's rights advocate testified in both the United States Congress and the Delaware General Assembly in the 1870s and 1880s.[308][309] In 1888, the Delaware chapter of the WCTU created a "franchise department" to advocate for women's suffrage in the state.[310] In 1895, the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) was formed.[311][312] DESA educated people in the state on women's suffrage and lobbied legislators.[313] In 1897, the state held a constitutional convention and activists from NAWSA came to help influence delegates to vote for suffrage.[314] While it was proposed that the word "male" not be added to the description of a legal voter, the measure did not pass.[311] In 1900, Delaware did allow some women who paid property taxes to vote for school commissioners.[308]

In 1913, one of the first suffrage parades in the state was held in Arden, Delaware.[315] Also in 1913, Rosalie Gardiner Jones hiked through Delaware on the way to the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C.[316] That year, Mabel Vernon of Wilmington, Delaware opened Congressional Union (later the National Woman's Party) headquarters in the state.[317] Vernon help pioneer new tactics in Delaware to support women's suffrage.[318] Vernon and Florence Bayard Hilles were also a more militant activists, and were part of the Silent Sentinels.[319][317] One Sentinel, Annie Arniel from Delaware, spent a total of 103 days in jail for her picketing of the White House.[320]

A petition drive in support of a federal women's suffrage amendment was kicked off in Wilmington in May 1918.[321] Suffrage headquarters were set up in Dover, Delaware by NAWSA organizer, Maria McMahon, in January 1919.[322] Activists saw signs that the federal amendment would pass the U.S. Congress.[323] The General Assembly called a special session on March 22, 1920 to consider the federal amendment.[324] Delaware could have been the 36th and last state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.[325] The entire country had their eyes on Delaware.[319] Both suffragists and anti-suffragists campaigned heavily in the state and testified at the General Assembly.[326] A personal grudge between a state representative and the governor turned the ratification into a proxy fight.[327] The General Assembly was never able to ratify the amendment before the close of the session on June 2.[328] Delaware belatedly ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on March 6, 1923.[329]

Florida

Ella C. Chamberlain was the major force behind women's suffrage in Florida between 1892 and 1897.[330][331] She was responsible for a suffrage department in a Tampa, Florida newspaper and was president of the Florida Woman Suffrage Association.[332][333] After Chamberlain left Florida in 1897, the suffrage movement stalled until around 1912.[334] That year, Jacksonville, Florida started the Equal Franchise League of Florida.[331][335] in 1913, two women attempted to vote in a bond election in Orlando, Florida, but were denied.[336][337] In 1915, the city of Fellsmere, Florida allowed women to vote due to a technicality in the city charter.[338] In 1918, several cities also passed municipal suffrage bills.[339][340] Florida did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until May 13, 1969.[341]

Georgia

The first women's suffrage group in Georgia was organized by Helen Augusta Howard in the early 1890s.[342] The group, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA) opposed taxation without representation.[343] Howard was able to persuade NAWSA to hold their annual convention in Atlanta in 1895, the first time the convention was held outside of Washington, D.C.[344][345] GWSA continued to fight for not only equal suffrage, but for other women's rights issues.[346] Membership in GWSA grew during the 1910s and when Rebecca Latimer Felton joined in 1912, the group received additional publicity.[347] A Men's League for Woman Suffrage and a youth suffrage group were formed in 1913.[348][349] In the next years, activists worked to get women's suffrage measures to pass in the state legislature, but were unsuccessful.[350][351] The city of Waycross, Georgia, however, passed a limited suffrage bill in 1917 allowing women to vote in municipal primary elections.[352] In Atlanta, women won the right to vote in municipal elections in 1919.[352] In July 1919, the Georgia Legislature considered the Nineteenth Amendment.[353] On July 24, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment.[354][355] Even after the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land, Georgia did not allow women to vote right away.[356] Because of voter registration rules, women could not vote in the 1920 presidential election.[357] The first time women voted statewide was in 1922.[358] African-American and Native American women were still excluded from voting.[359]

Kentucky

In 1838, Kentucky passed the first statewide woman suffrage law (since New Jersey revoked theirs with their new constitution in 1807) – allowing female heads of household to vote in elections deciding on taxes and local boards for the new county "common school" system. The law exempted the cities of Louisville, Lexington and Maysville since they had already adopted a system of public schools.[360] Kentucky was crucial as a gateway to the South for women's rights activists. Lucy Stone came through Louisville in November 1853 – wearing her own version of Amelia Bloomer trousers – earned $600 with thousands packing the halls each night.[361] After the Civil War, when the 13th Amendment was ratified by 2/3 of the states (not including Kentucky) on January 1, 1866, Lexington's Main Street was filled with African Americans in a military parade, followed by Black businesspeople and several hundred children with political speeches at Lexington Fairgrounds (now the University of Kentucky). By March a Black Convention was held in Lexington to discuss equal rights for Blacks. The next year, for July 4, a barbecue organized in Lexington by Black women included speeches made by both Black and by White speakers in favor of black suffrage and ratification of the 14th Amendment. That fall, another Black Convention included a debate on how to gain full civil rights for Blacks, including the right to vote and the right to testify in court against whites.[362] From the 11th National Women's Rights Convention and a merger with former abolitionists, the American Equal Rights Association formed to lobby the new federal government and the states for full rights for all citizens. In 1867 Virginia Penny of Louisville was elected Vice-President - her first book, The Employments of Women: A Cyclopaedia of Woman's Work was recently published (1863).[363] Also in 1867, the first suffrage association in the South is in Kentucky – Glendale, with 20 members.[364] Also, first in the South, were the two suffrage associations - one in Madison County and the other in Fayette County - started in the 1870s by Mary Barr Clay who has already begun serving in both the national suffrage associations (NWSA and AWSA) as vice-president. In October 1881, the AWSA held its national convention in Louisville, Kentucky - the first such convention south of the Mason-Dixon line. At this convention, the first statewide suffrage association in Kentucky was founded, and Laura Clay was elected president. In July 1887 Mary E. Britton spoke for woman suffrage at the Colored Teachers Association meeting in Danville, Kentucky.

When the NAWSA was formed in 1890, Laura Clay became the main voice for Southern white clubwomen. She led many campaigns through the South and the West on behalf of the NAWSA while she continues to support efforts in Kentucky to proliferate city/county suffrage associations—seven of them by 1890. In February 1894 Sallie Clay Bennett (Laura's older sister) spoke on behalf of the NAWSA before the U.S. Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage emphasizing the right of black men and women to vote because all were citizens. Mrs. Bennett wrote a political treatise that was presented to Congress by Senator Lindsay and Rep McCreary on behalf of the NAWSA, "asking Congress to protect white and black women equally with black men against State denial of the right to vote for members of Congress and the Presidential electors in the States..." – writing private letters to every member of Congress and sending copies to editors of newspapers in every state.[365] Eugenia B. Farmer of Covington figured out that the charters for second-class cities in Kentucky were up for renewal and the Kentucky Equal Rights Association (KERA) lobbied successfully in the Kentucky Constitutional Convention to get the legislature to grant those municipalities the right to grant woman suffrage.[366] In March 1894 the Kentucky General Assembly granted school suffrage to women in the cities of Lexington, Covington and Newport; and, Josephine Henry succeeded in her lobbying for the state law for a Married Woman's Property Act. In 1902, because of the fear of an organized bloc of Lexington's African-American women registered to vote for school board members in the Republican Party, the Kentucky legislature revoked this partial suffrage. The Kentucky Association of Colored Women's Clubs formed in 1903 with 112 clubs, and suffrage is a part of the efforts undertaken by their clubs. The newly organized Kentucky Federation of Women's Clubs (whites only) formed and lobbied to regain school suffrage in Kentucky, finally winning it back in 1912 with an added proviso (just for women) of a "literacy" test.

In 1912 Laura Clay stepped down as president of KERA in favor of her distant cousin Madeline McDowell Breckinridge;[367] and in 1913 Clay was elected to lead a new organization, the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference, founded to win the vote through state enactment. In August 1918 Laura Clay and Mrs. Harrison G. (Elizabeth Dunster) Foster, formerly a leader of suffrage in Washington, formed the Citizens Committee which formally broke with KERA - and the next year, Laura Clay finally quit working for NAWSA and turned to securing a state suffrage bill in Kentucky.[368] Presidential suffrage for women in Kentucky is signed into law on March 29, 1920.

In the early days of January 1920, National Woman's Party members Dora Lewis and Mabel Vernon travel to Kentucky to assure success, and on January 6, Kentucky became the 23rd state to ratify the 19th Amendment. On December 15, 1920, the Kentucky Equal Rights Association officially becomes the Kentucky League of Women Voters. Mary Bronaugh of Louisville was the first president of the state chapter.

See more on this state's suffrage history at the Kentucky Woman Suffrage Project.

Maryland

The 19th Amendment, which ensures women the right to vote, was ratified August 18, 1920.[369] However, Maryland did not ratify the Amendment until March 29, 1941. The Maryland Senate and the Maryland House of Delegates both voted against women's suffrage in 1920.[370] In the time between the United States and Maryland approving the amendment, women fought very hard for their rights. In Maryland, there were suffragists and suffrage groups all protesting for women's rights.

Edith Houghton Hooker, born in Buffalo, New York in 1879, was a suffragist in Maryland.[371] She graduated from Bryn Mawr College and later enrolled in the Johns Hopkins University Medical School, where she was one of the first women accepted into the program.[371] Hooker was an active member of the suffrage movement.[372] She and her husband, Donald Russell Hooker, were responsible for establishing the Planned Parenthood Clinic in Baltimore.[372] Hooker also established the Just Government League of Maryland, which brought the question of women's suffrage to the people of Maryland.[373] Hooker also founded the Maryland Suffrage News.[374] This newspaper was designed to help unite the suffrage organizations scattered across the state in order to bring pressure to the legislature to be more sympathetic to the issues of women, and to serve as a source of information about suffrage to the women of the state because mainstream papers were virtually blind to the existence of the movement.[374] Hooker saw the need for a focus on passing a national amendment, so she did all she could to get the amendment approved.[374]

Henrietta ("Etta") Haynie Maddox was the first woman to graduate from Baltimore Law School in 1901, and later to be admitted to the Maryland bar.[375] However, initially she was not permitted to take the exam.[376] The Maryland Court of Appeals rejected her application on the grounds that the wording of Maryland's law only permitted male citizens to practice law.[376][377] Therefore, Maddox and several other female attorneys from other states went to Maryland's General Assembly to lobby for women to be admitted to the Maryland bar. In 1902, a bill introduced by Senator Jacob M. Moses was passed, permitting women to practice law in Maryland.[378] Maddox passed the bar exam with distinction and in September 1902, she was the first woman to become a licensed lawyer in Maryland.[379]

South Carolina

Women's suffrage in South Carolina began as a movement in 1898, nearly 50 years after the women's suffrage movement began in Seneca Falls, New York. The state's women suffrage movement was concentrated amongst a small group of women, with little-to-no support from the state's legislature.[380]

Virginia Durant Young, was a prominent figure in South Carolina's women's suffrage movement. Young was a temperance campaigner who expanded her efforts to push for votes for women in South Carolina elections.[381] Among the objections she argued against was a claim that, because polling booths were often located in bars, the act of voting would take women into unpleasant situations.[382] South Carolina's first women's suffrage movement was closely tied to the temperance movement lead by the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Young, with several other suffragists, formed the South Carolina Equal Rights Association (SCERA) in 1890.[381]

In 1892, described as a "staunch male supporter," General Robert R. Hemphill, a state legislator, introduced an amendment for women's suffrage.[380] This amendment was voted down 21 to 14.[383] Over the 1890s a number of laws were revised to extend women more property rights.[383] Virginia Durant Young died in 1906, and with her death came the end of SCERA and other efforts within the state for women's suffrage.[380]

Women's suffrage finally came to South Carolina through the Nineteenth Amendment after the amendment was passed by Congress in 1919. South Carolina accepted the implications of the Nineteenth Amendment, but at the same time passed a law excluding women from jury duty within the state. South Carolina finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in 1969.[384]

Suffragist Virginia Durant Young's former home—which also served as the office for her newspaper, the Fairfax Enterprise—was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 8, 1983.[385][386]

Tennessee

Woman suffrage entered the public forum in Tennessee in 1876 when a Mississippi suffragist, Mrs. Napoleon Cromwell, spoke before the male delegates to the state Democratic convention held in Nashville. Her ten-minute speech asked the assembly to adopt a resolution for woman suffrage. Her appeal was based in terms of white supremacy. She reasoned that the white race would not be united unless white women were enfranchised. She pointed out that former male slaves could vote, but the wives, daughters, mothers, and sisters of those present at the convention could not. The delegates applauded but they also laughed, treating her speech as a joke. No resolution was passed.[387]

After the Women's Christian Temperance Union national convention in Nashville in 1887, and a powerful appeal by suffragist Rev. Anna Howard Shaw, a group of women in Memphis organized the first woman suffrage league in the state in 1889. Lide Meriwether was elected president and she became active in the National American Woman Suffrage Association as a speaker for other states. In 1895 Meriwether persuaded Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt to come to Memphis where they spoke to white and African American groups and were lauded by the Nineteenth Century Club, the Woman's Council, and the Woman's Club.[388] By 1897 there were ten new clubs in Tennessee, with the largest still in Memphis. A state convention was organized for Nashville that year with Laura Clay of Kentucky and Frances Griffin of Alabama as featured speakers. This convention then formed the Tennessee Equal Rights Association, electing Lide Meriwether president and Bettie M. Donelson of Nashville, secretary.[389] Two separate state associations formed in 1914—the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association and the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association, Incorporated. They both affiliated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association and in 1918 combined to form the Tennessee Woman Suffrage Association.[390]

Due to the work by suffragists, in 1919 the Tennessee legislature passed an amendment to the state constitution granting only presidential and municipal suffrage for women. When the Susan B. Anthony amendment came to the Tennessee legislature, thirty-five other states had already ratified it. There was some controversy about the legitimacy of a state constitutional stipulation that a federal amendment could only be voted upon by a legislature that was in place before the amendment was submitted. It took a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court to cause the legislature to reconsider this issue. In addition, Governor Roberts was getting pressure - even from President Woodrow Wilson - to call a special legislative session to consider ratification of the 19th Amendment. Finally, the legislature was called on August 7, 1920. Pro- and anti-suffragist forces came to lobby for their cause.[391] After several days of hearings and debate, the Tennessee State Senate voted for ratification of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment on August 13. On August 17, the house committee on constitutional convention and amendments urged ratification. Debate followed and eventually the house adopted ratification by a majority of fifty to forty-six.[392] With Tennessee as the thirty-sixth state to ratify, the fight for the Nineteenth Amendment was over.[393]

Texas

Women in Texas did not have any voting rights when Texas was a republic (1836-1846) or after it became a state in 1846.[394] Suffrage for Texas women was first raised at the Constitutional Convention of 1868-1869 when Republican Titus H. Mundine of Burleson County proposed that the vote be given to all qualified persons regardless of gender.[394] The committee on state affairs approved Burleson's proposal but the convention rejected it by a vote of 52 to 13.[394] The first suffrage organization in Texas was the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) which was organized in Dallas in May 1893 by Rebecca Henry Hayes of Galveston and which was active until 1895. TERA had auxiliaries in Beaumont, Belton, Dallas, Denison, Fort Worth, Granger, San Antonio, and Taylor.[395]

Suffragists in Texas formed the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA) in 1903[396] and renamed it the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in 1916.[394] The association was the state chapter of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[395] Annette Finnigan of Houston was the first president.[394] During Finnigan's presidency, TWSA attempted to organize women's suffrage leagues in other Texas cities but found little support.[394] When Finnigan moved from Texas in 1905, the association became inactive.[396]

In April 1913, 100 Texas suffragists met in San Antonio and reorganized TWSA[394] with seven local chapters sending delegates.[395] The delegates elected Mary Eleanor Brackenridge from San Antonio as president. Annette Finnigan, who had returned to Houston in 1909, succeeded Brackenridge as president in 1914, followed by Minnie Fisher Cunningham from Galveston in 1915.[394] By 1917, there were 98 local chapters of TESA throughout Texas.[394] In January 1916, 100 suffragists chartered the state branch of the National Woman's Party (NWP) in Houston.[397] However, most Texas suffragists belonged to the more moderate Texas Equal Suffrage Association.[397]

Texas suffragists publicized their cause through sponsoring lectures and forums, distributing pamphlets, keeping the issue in local newspapers, marching in parades, canvassing their neighborhoods, and petitioning their legislators and congressmen.[394] Many suffragists in Texas used nativist and racist arguments to advocate for women's suffrage.[397] After the United States entered World War I, Texas suffragists also argued for the vote on the basis of their war work and patriotism.[398]

In 1915, Texas suffragists came within two votes in the Texas legislature of achieving an amendment to the state constitution giving women the vote.[395] In March 1918, suffragists led the effort to get women the vote in state primary elections.[395] In seventeen days, TESA and other suffrage organizations registered approximately 386,000 Texas women to vote in the Democratic primary election in July 1918, which was the first time that women in Texas were able to vote.[395] Texas suffragists then turned their attention to lobbying their federal representatives to support the Susan B. Anthony amendment to the federal constitution.[395] Both Texas senators and ten of eighteen U.S. representatives from Texas voted for the federal amendment on June 4, 1919.[399] Later that month, Texas became the first state in the South and the ninth state in the United States to ratify the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[394] The Texas House approved the federal amendment on June 24, 1919 by a vote of 96 to 21 and the Texas Senate approved it on June 28, 1919 by a voice vote.[399]

Virginia

Women's suffrage in Virginia began 1870 with the founding of the Virginia State Woman Suffrage Association by Anna Whitehead Bodeker.[400][401] Bodeker tried to stir up public support for women's suffrage by publishing newspaper articles and inviting nationally known suffragists to speak. However, post-Civil War societal demands to uphold traditional values of womanhood won out, and the Virginia State Woman Suffrage Association shut down less than a decade after its founding.[400][401] In 1893, Orra Gray Langhorne founded the Virginia Suffrage Society as part of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but it folded before the turn of the century due to low membership numbers.[402]

In November 1909, about 20 Richmond-area activists—including Lila Meade Valentine, Kate Waller Barrett, Adele Goodman Clark, Nora Houston, Kate Langley Bosher, Ellen Glasgow, Mary Johnston—founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia.[400][403] A few months after its founding, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia joined NAWSA.[400] The league had about 100 members in its first year of operation. In 1917, it had more than 15,000. By 1919, the league had 32,000 members and was the largest political organization in the state of Virginia.[400]

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia educated Virginia's citizens and legislators by canvassing houses, distributing pamphlets, and sending its members on speaking tours around the state.[400] The league also regularly petitioned Virginia's General Assembly to add a women's voting rights amendment to the state constitution, bringing the issue to the floor in 1912, 1914, and 1916; they were defeated each time.[400][404] Meanwhile, Virginia suffragists encountered strong opposition to their cause by an anti-suffragist movement, headed by the Virginia Association Opposed to Women's Suffrage, that tapped into racial fears and traditional, conservative beliefs about the role of women in society.[403]

When the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment in June 1919, Virginia suffragists lobbied for ratification, but Virginia's politicians refused. However, women of Virginia got the right to vote in August 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment became law after it was ratified by 36 states.[400]

Virginia wouldn't ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952.[400]

West Virginia

As all of West Virginia is encapsulated by the Southern Appalachian mountains, much of its cultural norms are similar to the rural South, including attitudes about women's roles.[405] As early as 1867, a state senator, Rev. Samuel Young, presented a resolution calling for the right for women to vote. But when the Southern Committee for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) sought support in West Virginia, they did not hear of any women interested in supporting woman suffrage. Two NAWSA organizers came to the state in the fall of 1895 and helped organize several local clubs and a state convention in Grafton. The West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association (WVSEA) formed in Grafton, West Virginia in November 1895, though this all-white suffrage club was supported by suffragists concentrated primarily in only five cities: Wheeling, Fairmont, Morgantown, Huntington, and Parkersburg.[406] In 1898 the Charleston Woman's Improvement League was organized as a member of the National Association of Colored Women and suffrage was an important part of their work.[407] Though the national Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) had already included winning the franchise in its departmental structure, the West Virginia WCTU did not officially endorse women's suffrage until 1900.[408] Several more attempts in the legislature over the years also met with defeat, though in 1915 the legislature called for a statewide constitutional referendum for woman suffrage. It was soundly defeated in all the counties but two (Brooke and Handcock) where an NAWSA organizer, Eleonore Greene,[409] had been working to support the effort. When pro-suffrage Governor John J. Cornwell added the federal amendment to the special session of the legislature in February 1920, it was ratified. Lenna Lowe Yost of Basnettville, West Virginia, was WVSEA president and had organized the petition drive as well as the "living petition" of suffragists who greeted and lobbied the legislators as they prepared to vote in the special session. On March 3, the House of Delegates voted for the amendment.[410] However, the state Senate was deadlocked in a tie. Sen. Jesse Bloch of Wheeling returned from a California vacation just in time to break the tie, and with a fifteen to fourteen vote in the Senate on March 10, the legislature sent the ratification bill to the Governor for his signature. West Virginia became the thirty-fourth of the thirty-six states needed to ratify the federal amendment for woman suffrage.

Former territories

Alaska

White women in Alaska were able to vote in school board elections in 1904.[411][412] Many white women's rights activists in the state were involved with the WCTU.[413] Cornelia Templeton Hatcher, an active WCTU member also worked towards women's suffrage in the state.[413] Lena Morrow Lewis also campaigned for women's suffrage in Alaska.[414] The press of Alaska was favorable towards women's suffrage.[415] Representatives both in the United States Congress and in the Territorial legislature were supportive of legislation for equal suffrage.[416][417] On March 21, 1913 a law allowing white and Black women to vote, but largely excluded Alaska Natives.[418] Because Alaska Natives were generally not considered citizens of the United States, they were not allowed to vote.[419] In 1915, the Territorial Legislature passed a law allowing Alaska Natives to vote if they gave up their "tribal customs and traditions."[420] Tillie Paul (Tlingit), who was arrested for helping Charlie Jones (Tlingit) to vote, set a precedent that Alaska Natives could vote.[421][422] In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act was passed.[423] The next year, Alaska passed a literacy test meant to suppress Alaska Native voters.[424] After years of protest against segregation in Alaska, the Territorial Legislature considered a civil rights bill in 1945.[425] During the proceedings, the testimony of Elizabeth Peratrovich (Tlingit) helped the bill to pass.[426] The passage of the Alaska Equal Rights Act of 1945 helped end segregation, but Alaska Natives still faced voter discrimination.[427][428] When Alaska became a state, the literacy test became more lenient.[429] In 1970, the state considered suffrage and a referendum passed, ending literacy tests.[429] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), modified in 1975, provided help for indigenous people who did not speak English.[430][431] To the present day, many Alaska Natives face significant barriers to voting.[432]

Hawaii