Winsford Mine

Winsford Mine (also known as Meadow Bank Mine) is a halite (rock salt) mine in the town of Winsford, Cheshire, England. The mine produces an average of 1,500,000 tonnes (1,700,000 tons) of rock salt a year, which is used to grit public roads in the United Kingdom during the winter months. Two other mines also produce rock salt within the United Kingdom, but Winsford has the biggest output of all three and has the largest market share.

Surface plant at Winsford Salt Mine | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

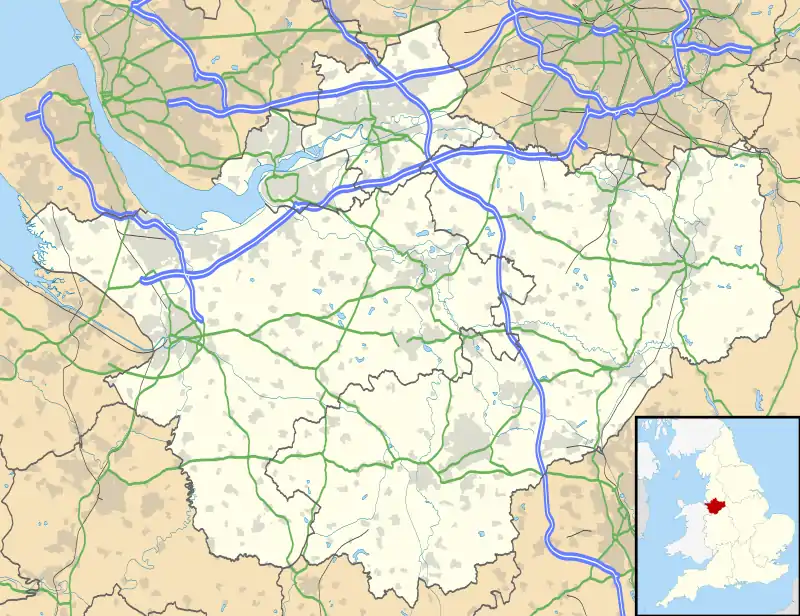

Winsford Mine Meadow Bank Mine Location within Cheshire | |

| Location | Winsford |

| County | Cheshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53.209°N 2.519°W |

| Production | |

| Products | Halite (rock salt) |

| Production | 2,200,000 tonnes (2,400,000 tons)[1] |

| Financial year | 2020 |

| Greatest depth | 150 metres (490 ft) |

| History | |

| Discovered | 1844 |

| Opened | 1844 |

| Active | 1844–1892 1928–present |

| Owner | |

| Company | Compass Minerals |

| Website | Official website |

| Year of acquisition | 2003 |

It is also Britain's oldest working mine.

History

The salt in the area was discovered by accident when workers were looking for coal reserves to heat saltpans.[2][3] It was opened out in 1844, but a downturn in the rock salt market led to its closure in 1892. It was re-opened in 1928 when a nearby salt mine, the Marston Mine in Northwich, was subjected to flooding after subsidence.[4][5][6] The salt was laid down during the Triassic period over 220 million years ago when the area was under a tropical sea, and later a briny lagoon.[7] Reserves in the mine area have an estimated life until the year 2076, though this is dependent on planning permissions.[8]

The mine, which is sometimes referred to by its old name of Meadow Bank Mine,[9] has over 260 kilometres (160 mi) of tunnels which are held in place by a room and pillar method of mining. This leaves around 25% of the available rock salt behind to support the roof of the mineworkings.[3] The salt content of the mined rock is around 92%, and whilst the majority of the product mined is used as road salt, some is used in fertiliser manufacture.[10][11]

Although the mine was mothballed between 1892 and 1928, it is Britain's oldest working mine.[12] It was granted an extension to its mining licence in 2012 which will see mining continuing to at least 2047.[13] The mine produces 950,000–1,000,000 tonnes (1,050,000–1,100,000 tons) of rock salt each year (30,000 tonnes (33,000 tons) a week at peak production) and has a marketshare of around 90%.[14] During the 19th century, export of the salt was by barge or boat on the River Weaver, but when the mine reopened in 1928, a railway connection was laid.[15]

In the heavy snowfall of January 2010, lorries were shown on national TV at the mine surface plant loading salt supplies for many local authorities in England who were running out of stock for their gritters. Then prime minister, Gordon Brown, issued a plea to the mine's owners to increase production.[16]

Of the three mines in the United Kingdom which produce rock salt, Winsford Mine has the largest marketshare. In 2004, 2,000,000 tonnes (2,200,000 tons) was the combined output from all three mines, with over 900,000 tonnes (990,000 tons) being mined at Winsford.[17][18]

Storage

In 2006, it was estimated that the mine had over 26,000,000 cubic metres (920,000,000 cu ft) of free space, a dry humidity, a near constant temperature, and unlike many old collieries, is gas free. Some of this has been given over to the storage of hazardous wastes which are non-radioactive.[19][20] The most notable storage commodity is documents and books; in 1998, Deepstore was created at Winsford Mine with documents form the National archives|National Archives stored there.[21] They are protected against heat, humidity, ultra-violet light, rodents and flooding.[22] The National Archives shelf space at Deepstore takes up over 32 kilometres (20 mi).[23]

Hazardous waste storage at the site was granted a licence extension in 2022 of twenty years on its original permission (which was until 2025). The company can now keep storing wastes until 2045.[24]

Production tonnages

- 1959 – 100,000 tonnes (110,000 tons)[25]

- 1960 – 300,000 tonnes (330,000 tons)[26]

- 1964 – 900,000 tonnes (990,000 tons)[26]

- 1969 – 1,300,000 tonnes (1,400,000 tons)[27]

- 1971 – 1,800,000 tonnes (2,000,000 tons)[26]

- 1995 – 1,000,000 tonnes (1,100,000 tons)[28]

- 2017 – 1,500,000 tonnes (1,700,000 tons)[1]

- 2020 – 2,200,000 tonnes (2,400,000 tons)[1]

Owners

References

- "Major Mines & Projects | Winsford Mine". miningdataonline.com. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- "Cheshire, U.K. | U.K.'s Largest Salt Mine". compassminerals.com. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- Jahangir, Rumeana (17 February 2016). "Inside the UK's largest salt mine". BBC News. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- "Rock Salt Mining | Cheshire Brine Subsidence Compensation Board". cheshirebrine.com. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- Wallwork, K. L. (July 1959). "The Mid-Cheshire Salt Industry". Geography. Taylor & Francis. 44 (3): 182. ISSN 0016-7487.

- Arnold, Michael (5 December 1968). "Winsford rock salt mine crisis". Winsford Chronicle. p. 1. ISSN 0962-5712.

- Wainwright, Martin (5 February 2013). "Rock salt mine's fight against nearby gas storage project nears the 11th hour". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- SMPF 2006, p. 5.

- "The Mines Regulations 2014". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- SMPF 2006, p. 6.

- Directory of Mines and Quarries (11 ed.). Keyworth: British Geological Survey. 2020. p. 1-71. ISBN 978-0-85272-789-8.

- "The Geological Society of London - Geology and HS2". geolsoc.org.uk. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- "Salt mine extends operational life". Northwich Guardian. 13 February 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- Jenkins, Russell (6 February 2009). "Cheshire mine digs deep to meet demands for rock salt". The Times. No. 69552. p. 19. ISSN 0140-0460.

- Miller, R. W. (1999). The Winsford & Over Branch. Usk: Oakwood Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-85361-546-2.

- Jenkins, Russell (8 January 2010). "The precious salt that can't be dug up quickly enough". The Times. No. 69839. p. 25. ISSN 0140-0460.

- SMPF 2006, pp. 4, 6.

- "Why Cheshire's worth its salt". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- SMPF 2006, p. 7.

- Vidal, John (8 January 2004). "Salt mine to become huge dump for toxic waste". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- "History Of The Salt Mine". deepstore.com. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- Coonan, Clifford (23 August 2011). "Hidden underground". The Independent. No. 7758. p. 23. ISSN 1741-9743.

- Kavanagh, Michael (21 January 2013). "Salt miner sees risk in gas storage plan". Financial Times. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- "Winsford Salt Mine: Hazardous waste storage extension approved". BBC News. 11 May 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- Gapper, Mark (11 December 1959). "Bacon and eggs in the salt mine". The Guardian. No. 35, 286. p. 9. OCLC 60623878.

- "No need to worry about traffic queues in Cheshire's Salt City". Liverpool Echo. No. 28, 670. 3 March 1972. p. 7. ISSN 1751-6277.

- "Rock salt orders behind". Winsford Chronicle. 15 January 1970. p. 1. ISSN 0962-5712.

- Edmonds, Mark (11 February 1995). "True Grit". The Daily Telegraph. No. 43, 433. p. 50. ISSN 0307-1235.

- Miller, R. W. (1999). The Winsford & Over Branch. Usk: Oakwood Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-85361-546-2.

- Miller, R. W. (1999). The Winsford & Over Branch. Usk: Oakwood Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-85361-546-2.

- Eadie, Alison (7 December 1992). "Snow is the icing on Salt Union's cake: Alison Eadie looks at how". The Independent. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- "Salt jobs 'are safe'". Warrington Guardian. 25 March 1998. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- "The History of Compass Minerals" (PDF). compassminerals.com. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

Sources

- Salt mineral planning factsheet (PDF). nora.nerc.ac.uk (Report). British Geological Surveylocation=Keyworth. 2006. Retrieved 26 August 2023.