Renewable energy in Brazil

As of 2018, renewable energy accounted for 79% of the domestically produced electricity used in Brazil.[1][2][3]

Brazil relies on hydroelectricity for 65% of its electricity,[1][2] and the Brazilian government plans to expand the share of wind energy (currently 11%), solar energy (currently 2.5%) and biomass[1][2] as alternatives. Wind energy has the greatest potential in Brazil during the dry season, so it is considered a hedge against low rainfall and the geographical spread of existing hydroelectric resources.

Brazil held its first wind-only energy auction in 2009, in a move to diversify its energy portfolio. Foreign companies scrambled to take part. The bidding lead to the construction of 2 gigawatts (GW) of wind production with an investment of about $6 billion over the following two years. Brazil's technical potential for wind energy is 143 GW due to the country's blustery 7,400 kilometres (4,600 mi) kilometres coastline where most projects are based. The Brazilian Wind Energy Association and the government have set a goal of achieving 20 GW of wind energy capacity by 2020 from the current 5 GW (2014).[4] The industry hopes the auction will help kick-start the wind-energy sector, which already accounts for 70% of the total in all of Latin America.[5]

According to Brazil's Energy Master-plan 2016-2026 (PDE2016-2026), Brazil is expected to install 18,5GW of additional wind power generation, 84% in the North-East and 14% in the South.[1]

Brazil started focusing on developing alternative sources of energy, mainly sugarcane ethanol, after the oil shocks in the 1970s. Brazil's large sugarcane farms helped the development. In 1985, 91% of cars produced that year ran on sugarcane ethanol. The success of flexible-fuel vehicles, introduced in 2003, together with the mandatory E25 blend throughout the country, have allowed ethanol fuel consumption in the country to achieve a 50% market share of the gasoline-powered fleet by February 2008.[6][7]

Total energy matrix and Electric energy matrix

The main characteristic of the Brazilian energy matrix is that it is much more renewable than that of the world. While in 2019 the world matrix was only 14% made up of renewable energy, Brazil's was at 45%. Petroleum and oil products made up 34.3% of the matrix; sugar cane derivatives, 18%; hydraulic energy, 12.4%; natural gas, 12.2%; firewood and charcoal, 8.8%; varied renewable energies, 7%; mineral coal, 5.3%; nuclear, 1.4%, and other non-renewable energies, 0.6%.[8]

In the electric energy matrix, the difference between Brazil and the world is even greater: while the world only had 25% of renewable electric energy in 2019, Brazil had 83%. The Brazilian electric matrix is composed of: hydraulic energy, 64.9%; biomass, 8.4%; wind energy, 8.6%; solar energy, 1%; natural gas, 9.3%; oil products, 2%; nuclear, 2.5%; coal and derivatives, 3.3%.[8]

Electricity

Hydroelectricity

Hydroelectric power plants produced almost 80% of the electrical energy consumed in Brazil (now 60%)[9]. Brazil has the third highest potential for hydroelectricity, following Russia and China.[10] At the end of 2021 Brazil was the 2nd country in the world in terms of installed hydroelectric power (109.4 GW).[11]

Itaipu power plant

The Itaipu Dam is the world's second largest hydroelectric power station by installed capacity. Built on the Paraná River dividing Brazil and Paraguay, the dam provides over 75% of Paraguay's electric power needs, and meets more than 20% of Brazil's total electricity demand. The river runs along the border of the two countries, and during the initial diplomatic talks for the dam construction both countries were suffering from droughts. The original goal was therefore to provide better management and utilization of water resources for the irrigation of crops. Argentina was also later incorporated in some of the governmental planning and agreements because it is directly affected, being downstream, by the regulation of the water on the river. If the dam were to completely open the water flow, areas as far south as Buenos Aires could potentially flood.

Construction of the dam started in 1975, and the first generator was opened in 1983. It is estimated that 10,000 locals were displaced by the construction of the dam, and around 40,000 people were hired to help with the construction of the project. Many environmental concerns were overlooked when constructing the dam, due to the trade-off considering the production of such a large amount of energy without carbon emissions, and no immediate harmful byproducts, such as with nuclear energy.

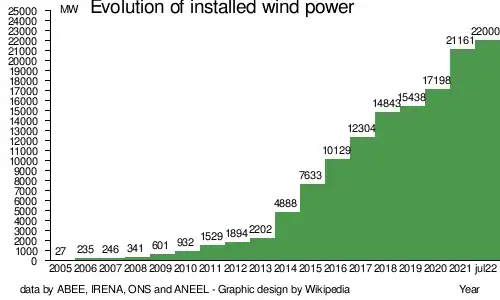

Wind power

In July 2022 Brazil reached 22 GW of installed wind power.[12][13] In 2021 Brazil was the 7th country in the world in terms of installed wind power (21 GW),[14][15] and the 4th largest producer of wind energy in the world (72 TWh), behind only China, USA and Germany.[16]

As of August 2021, the total installed wind power capacity in Brazil was 18.9 GW, with 16.4 GW in the Northeast Region and 2.0 GW in the South Region.[17]

Wind is more intense from June to December, coinciding with the months of lower rainfall intensity. This puts the wind as a potential complementary source of energy to hydroelectricity.[18]

Brazil's first wind energy turbine was installed in Fernando de Noronha Archipelago in 1992. Ten years later the government created the Program for Incentive of Alternative Electric Energy Sources (Proinfa) to encourage the use of other renewable sources, such as wind power, biomass, and small hydro. Since the inception of Proinfa, Brazil's wind energy production has grown from 22 MW in 2003 to 602 MW in 2009, and to over 8,700 MW by 2015.

Developing these wind power sources in Brazil is helping the country to meet its strategic objectives of enhancing energy security, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and creating jobs. The potential for this type of power generation in Brazil could reach up to 145,000 MW, according to the 2001 Brazilian Wind Power Potential Report by the Electric Energy Research Centre (Cepel).

While the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP15) was taking place in Copenhagen, Brazil's National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL) held the country's first ever wind-only energy auction. On December 14, 2009, around 1,800 megawatts (MW) were contracted with energy from 71 wind power plants scheduled to be delivered beginning July 1, 2012. The 716 MW Lagoa dos Ventos began operating in 2021.[19]

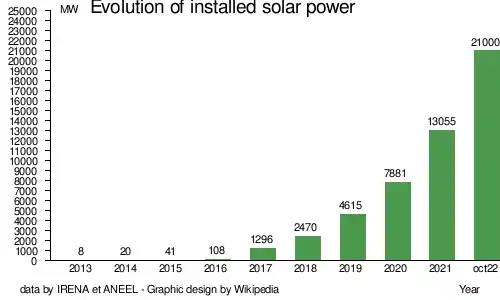

Solar power

In October 2022 Brazil reached 22 GW of installed solar power.[20][21] In 2021, Brazil was the 14th country in the world in terms of installed solar power (13 GW),[22] and the 11th largest producer of solar energy in the world (16.8 TWh).[16]

As of May 2022, according to ONS, total installed capacity of photovoltaic solar was 15.18 GW, with 10 GW of distributed solar (where Minas Gerais stood out with 1.73 GW, São Paulo with 1.29 GW and Rio Grande do Sul with 1.17 GW of this total) and 5.18 GW in solar plants (where Bahia, with 1,354 MW, Piauí, with 1,205 MW, Minas Gerais, with 730 MW, São Paulo, with 588 MW and Ceará, with 499 MW stood out)[23][24]

Brazil has one of the highest solar incidence in the world.[25]

The largest solar plants in Brazil consist of Ituverava and the Nova Olinda plants. The Ituverava solar plant produces 254 MW and the Nova Olinda plant produces 292 MW.[26]

Ethanol fuel

Brazil's ethanol program started in 1975, when soaring oil prices put a chokehold on the economy. Sugarcane was an obvious candidate, given Brazil's large amount of arable land and favourable climate.[27]

Most cars on the road today in Brazil can run on blends of up to 25% ethanol, and motor vehicle manufacturers already produce vehicles designed to run on much higher ethanol blends. Most car makers in Brazil sell flexible-fuel cars, trucks, and minivans that can use gasoline and ethanol blends ranging from pure gasoline up to 100% ethanol (E100). In 2009, 90% of cars produced that year ran on sugarcane ethanol.

Brazil is the second largest producer of ethanol in the world and is the largest exporter of the fuel. In 2008, Brazil produced 454,000 bbl/d of ethanol, up from 365,000 in 2007. All gasoline in Brazil contains ethanol, with blending levels varying from 20–25%. Over half of all cars in the country are of the flex-fuel variety, meaning that they can run on 100% ethanol or an ethanol-gasoline mixture. According to ANP, Brazil also produced about 20,000 bbl/d of biodiesel in 2008, and the agency has enacted a 3% blending requirement for domestic diesel sales.

The importance of ethanol in Brazil's domestic transportation fuels market is expected to increase in the future. According to Petrobras, ethanol accounts for more than 50% of current light vehicle fuel demand, and the company expects this to increase to over 80% by 2020. Because ethanol production continues to grow faster than domestic demand, Brazil has sought to increase ethanol exports. According to industry sources, Brazil's ethanol exports reached 86,000 bbl/d in 2008, with 13,000 bbl/d going to the United States. Brazil is the largest ethanol exporter in the world, holding over 90% of the global export market.[28]

Biomass

24mar2007.jpg.webp)

In 2020, Brazil was the 2nd largest country in the world in the production of energy through biomass (energy production from solid biofuels and renewable waste), with 15,2 GW installed.[29]

Biomass is a clean energy source used in Brazil. It reduces environmental pollution as it uses organic garbage, agricultural remains, wood shaving or vegetable oil. Refuse cane, with its high energetic value, has been used to produce electricity.[30] More than 1 million people in the country work in the production of biomass, and this energy represents 27% of Brazil's energetic matrix.[31]

The recent interest in converting biomass to electricity comes not only from its potential as a low-cost, indigenous supply of power, but for its potential environmental and developmental benefits. For example, biomass may be a globally important mitigation option to reduce the rate of CO2 buildup by sequestering carbon and by displacing fossil fuels. Renewably grown biomass contributes only a very small amount of carbon to the atmosphere. Locally, plantations can lessen soil erosion, provide a means to restore degraded lands, offset emissions and local impacts from fossil-fired power generation, and, perhaps, reduce demands on existing forests. In addition to the direct power and environmental benefits, biomass energy systems offer numerous other benefits, especially for developing countries such as Brazil. Some of these benefits include the employment of underutilized labour and the production of co- and by-products, for example, fuelwood.

Nearly all of the experiences with biomass for power generation are based on the use of waste and residue fuels (primarily wood/wood wastes and agricultural residues). The production of electric power from plantation-grown wood is an emerging technology with considerable promise. However, actual commercial use of plantation-grown fuels for power generation is limited to a few isolated instances. Wood from plantations is not an inexpensive energy feedstock, and as long as worldwide prices of coal, oil and gas are relatively low, the establishment of plantations dedicated to supplying electric power or other higher forms of energy will occur only where financial subsidies or incentives exist or where other sources of energy are not available.

Where biomass plantations are supplying energy on a commercial basis in Brazil, the Philippines and Sweden, it can be shown that a combination of government policies or high conventional energy prices have stimulated the use of short-rotation plantations for energy. Brazil used tax incentives beginning in the mid-1960s to initiate a reforestation program to provide for industrial wood energy and wood product needs. As a consequence of the Brazilian Forestry Code with its favourable tax incentives, the planted forest area in Brazil increased from 470,000 hectares to 6.5 million hectares by 1993. With the discontinuation of the tax incentives in 1988, plantation establishment in Brazil has slowed, although the commercial feasibility of using eucalyptus for energy and other products has been clearly demonstrated.[32]

External funding

The European Investment Bank provided a €200 million loan starting 2021 to support renewable energy projects, specifically to establish a wind farm and solar power plant.[33][34][35] This will support a series of onshore wind farms divided into two clusters, in Paraiba, Piauí, and Bahia. A solar photovoltaic plant will be built 10 km away from the Paraiba wind farm, with a total capacity of 574 MW (425 MW of wind power and 149 MW of solar power).[35]

See also

References

- "Plano Decenal de Expansão de Energia 2026". EPE (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Invest in Brazil - Brazilian M&A Guide 2018". CAPITAL INVEST. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Renewable energy in Brazil".

- "ABEEólica - Associação Brasileira de Energia Eólica". ABEEólica.

- Walzer, Robert P. (9 November 2009). "Brazilian Wind Power Gets a Boost". Green Blog.

- Agência Brasil (15 July 2008). "ANP: consumo de álcool combustível é 50% maior em 2007" (in Portuguese). Invertia. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- Samora, Roberto (3 June 2009). "Gabrielli: etanol reduzirá mercado de gasolina a 17% até 2020".

- "MATRIZ ENERGÉTICA". www.epe.gov.br.

- {Source missing}

- "Hydro Electricity in Brazil".

- "RENEWABLE CAPACITY STATISTICS 2022" (PDF). IRENA. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- "Eólica supera 22 GW em operação no Brasil". MegaWhat ⚡.

- "Brasil atinge 21 GW de capacidade instalada de energia eólica" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Valor. 21 January 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "RENEWABLE CAPACITY STATISTICS 2021" (PDF).

- "Global wind statistics" (PDF). IRENA. 22 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo (27 October 2022). "Energy". Our World in Data – via ourworldindata.org.

- "Boletim Mensal de Geração Eólica Agosto/2021" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Operador Nacional do Sistema Elétrico - ONS. 29 September 2021. pp. 6, 13. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- "G1 > Ciência e Saúde - NOTÍCIAS - Leilão em dezembro busca impulsionar geração de energia por ventos no Brasil". g1.globo.com.

- Lewis, Michelle (11 June 2021). "South America's largest wind farm starts commercial operations". Electrek.

- "Solar atinge 21 GW e R$ 108,6 bi em investimentos no Brasil – CanalEnergia". www.canalenergia.com.br.

- "Brasil é 4º país que mais cresceu na implantação de energia solar em 2021" (in Brazilian Portuguese). R7. 25 April 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- RENEWABLE CAPACITY STATISTICS 2022

- "Boletim Mensal de Geração Solar Fotovoltaica Agosto/2021" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Operador Nacional do Sistema Elétrico - ONS. 29 September 2021. pp. 6, 12. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- "Brasil ultrapassa marca de 10 GW em micro e minigeração distribuída". Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica.

- Ramos Martins, Fernando; Bueno Pereira, Enio; Luna de Abreu, Samuel; Colle, Sergio. "Brazilian Atlas for Solar Energy Resource: SWERA Results" (PDF). Retrieved 1 April 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Enel Starts Operation of South America's Two Largest Solar Parks in Brazil". WebWire. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "USATODAY.com - Brazil hopes to build on its ethanol success". usatoday30.usatoday.com.

- "U.S. Energy Information Administration - EIA - Independent Statistics and Analysis". www.eia.gov.

- "RENEWABLE CAPACITY STATISTICS 2021 page 41" (PDF). Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "Why saving energy matters to the country and the planet". www.natureba.com.br.

- Ambientebrasil, Redação (23 January 2009). "Biomassa: uma energia brasileira".

- Bioenergy - Biomass in Brazil

- Terra, Nana. "Wind energy in Brazil breaks records and creates jobs". www.airswift.com. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- "Neoenergia gets EIB loan for 1.2 GW of Brazilian renewables". Renewablesnow.com. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- Azzopardi, Tom. "Iberdrola subsidiary Neoenergia signs wind PPA with Brazilian conglomerate". www.windpowermonthly.com. Retrieved 5 April 2022.