Wilson effect

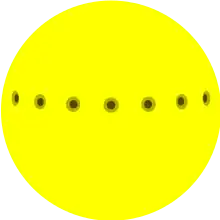

In astronomy, the Wilson effect is the perceived depression of a sunspot's umbra, or center, in the Sun's photosphere. The magnitude of the depression is difficult to determine, but may be as large as 1,000 km.

Sunspots result from the blockage of convective heat transport by intense magnetic fields. Sunspots are cooler than the rest of the photosphere, with effective temperatures of about 4,000°C (about 7,000°F). Sunspot occurrence follows an approximately 11-year period known as the solar cycle, discovered by Heinrich Schwabe in the 19th century.

History

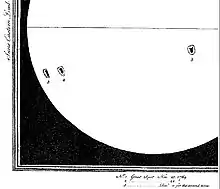

In 1769, during solar cycle 2, Scottish astronomer Alexander Wilson, working at the Macfarlane Observatory, noticed that the shape of sunspots noticeably flattened as they approached the Sun's limb due to solar rotation.[1] These observations showed that sunspots were features on the solar surface, as opposed to minor planets or objects above it. Moreover, he observed what is now termed the Wilson effect: the penumbra and umbra vary in the manner expected by perspective effects if the umbrae of the spots are in fact slight depressions in the surface of the photosphere.[2]

Alternate interpretations

While the surface-depression interpretation of the Wilson effect is widespread, Bray and Loughhead contended that "the true explanation of the Wilson effect lies in the higher transparency of the spot material compared to the photosphere".[1]: 93–99 A similar interpretation was expressed by C.H. Tong.[3]

References

- R.J. Bray and R.E. Loughhead (1965) Sunspots, page 4 "Discovery of the Wilson Effect", John Wiley & Sons

- John H. Thomas and Nigel O. Weiss (1991) Sunspots:Theory and Observations, page 5: "Wilson depression", Kluwer Academic Publishers

- C.H. Tong (2005) "Imaging sunspots using helioseismic methods", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 363:2761–75

- C.A. Young (1882) The Sun, page 126, Kegan Paul.