William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk

William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, KG (16 October 1396 – 2 May 1450), nicknamed Jackanapes, was an English magnate, statesman and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. He became a favourite of the weak king Henry VI of England, and consequently a leading figure in the English government where he became associated with many of the royal government's failures of the time, particularly on the war in France. Suffolk also appears prominently in Shakespeare's Henry VI, parts 1 and 2.

William de la Pole | |

|---|---|

| 1st Duke of Suffolk | |

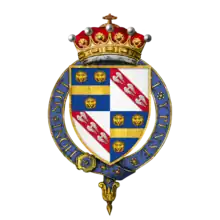

Quartered arms of William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, at the time of his installation as a knight of the Order of the Garter | |

| Born | 16 October 1396 Cotton, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 2 May 1450 (aged 53) English Channel (near Dover, Kent) |

| Buried | Carthusian Priory, Hull |

| Spouse(s) | Alice Chaucer (1430–1450, wid.) |

| Issue | John de la Pole, 2nd Duke of Suffolk Jane de la Pole (illegitimate) |

| Father | Michael de la Pole, 2nd Earl of Suffolk |

| Mother | Katherine de Stafford |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | 1415–1437 |

| Conflicts |

|

He fought in the Hundred Years' War and participated in campaigns of Henry V,[1] and then continued to serve in France for King Henry VI. He was one of the English commanders at the failed Siege of Orléans. He favoured a diplomatic rather than military solution to the deteriorating situation in France,[1][2] a stance which would later resonate well with King Henry VI.

Suffolk became a dominant figure in the government, and was at the forefront of the main policies conducted during the period.[3] He played a central role in organizing the Treaty of Tours (1444), and arranged the king's marriage to Margaret of Anjou. At the end of Suffolk's political career, he was accused of maladministration by many and forced into exile. At sea on his way out, he was caught by an angry mob, subjected to a mock trial, and beheaded.

His estates were forfeited to the Crown but later restored to his only son, John. His political successor was the Duke of Somerset.

Biography

William de la Pole was born in Cotton, Suffolk, the second son of Michael de la Pole, 2nd Earl of Suffolk, by his wife Katherine de Stafford, daughter of Hugh de Stafford, 2nd Earl of Stafford, KG, and Philippa de Beauchamp.

Almost continually engaged in the wars in France, he was seriously wounded during the Siege of Harfleur (1415), where his father died from dysentery.[4] Later that year his elder brother Michael, 3rd Earl of Suffolk, was killed at the Battle of Agincourt,[4] and William succeeded as 4th earl. He served in all the later French campaigns of the reign of Henry V, and in spite of his youth held high command on the marches of Normandy in 1421–22.

In 1423 he joined Thomas, Earl of Salisbury, in Champagne. He fought under John, Duke of Bedford, at the Battle of Verneuil on 17 August 1424, and throughout the next four years was Salisbury's chief lieutenant in the direction of the war.[1] He became co-commander of the English forces at the Siege of Orléans (1429), after the death of Salisbury.

When the city was relieved by Joan of Arc in 1429, he managed a retreat to Jargeau where he was forced to surrender on 12 June. He was captured by a French squire named Guillaume Renault. Admiring the young soldier's bravery, the earl decided to knight him before surrendering. This dubbing has remained famous in French history and literature and has been recounted by the writer Alexandre Dumas. He remained a prisoner of Charles VII for two years, and was ransomed in 1431, after fourteen years' continuous field service.

After his return to the Kingdom of England in 1434, he was made Constable of Wallingford Castle. He became a courtier and a close ally of Cardinal Henry Beaufort. Despite the diplomatic failure of the Congress of Arras, the cardinal's authority remained strong and Suffolk gained increasing influence.[1]

His most notable accomplishment in this period was negotiating the marriage of King Henry VI with Margaret of Anjou in 1444, which he achieved despite initial reluctance, and included a two years' truce.[1] This earned him a promotion from Earl to Marquess of Suffolk. However, a secret clause was put in the agreement which gave Maine and Anjou back to France, which was to contribute to his downfall.

With the deaths in 1447 of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (shortly after his arrest for treason), and Cardinal Beaufort, Suffolk became the principal power behind the throne of the weak and compliant Henry VI. In short order, he was appointed Chamberlain, Admiral of England, and to several other important offices. He was created Earl of Pembroke in 1447, and Duke of Suffolk in 1448. However, Suffolk was suspected of responsibility in Humphrey's death,[1] and later of being a traitor.

On 16 July he met in secret with Jean, Count de Dunois, at his mansion of the Rose in Candlewick Street, the first of several meetings in London at which they planned a French invasion. Suffolk passed Council minutes to Dunois, the French hero of the Siege of Orleans. It was rumoured that Suffolk never paid his ransom of £20,000 owed to Dunois. The Lord Treasurer, Ralph Cromwell, wanted heavy taxes from Suffolk; the duke's powerful enemies included John Paston and Sir John Fastolf. Many blamed Suffolk's retainers for lawlessness in East Anglia.[5]

Before he left on exile, exile that would lead to his death and beheading on the ship before he cleared England he sat down and wrote a letter to his boy, John, just eight years old and presumably still with his mother Alice Chaucer. The letter survives, and it helps bring a medieval character to life.

My dear and only well-beloved son, I beseech our Lord in Heaven, the Maker of all the World, to bless you, and to send you ever grace to love him, and to dread him, to the which, as far as a father may charge his child, I both charge you, and pray you to set all your spirits and wits to do, and to know his holy laws and commandments, by the which you shall, with his great mercy, pass all the great tempests and troubles of this wretched world.

And that also, knowingly, you do nothing for love nor dread of any earthly creature that should displease him. And there as any frailty maketh you to fall, beseech his mercy soon to call you to him again with repentance, satisfaction, and contrition of your heart, never more in will to offend him.

Secondly, next him above all earthly things, to be true liegeman in heart, in will, in thought, in deed, unto the king our aldermost high and dread sovereign lord, to whom both you and I be so much bound to; charging you as father can and may, rather to die than to be the contrary, or to know anything that were against the welfare or prosperity of his most royal person, but that as far as your body and life may stretch you live and die to defend it, and to let his highness have knowledge thereof in all the haste you can.

Thirdly, in the same way, I charge you, my dear son, always as you be bounden by the commandment of God to do, to love, to worship, your lady and mother; and also that you obey always her commandments, and to believe her counsels and advices in all your works, the which dread not but shall be best and truest to you. And if any other body would steer you to the contrary, to flee the counsel in any wise, for you shall find it naught and evil.

Furthermore, as far as father may and can, I charge you in any wise to flee the company and counsel of proud men, of covetous men, and of flattering men, the more especially and mightily to withstand them, and not to draw nor to meddle with them, with all your might and power; and to draw to you and to your company good and virtuous men, and such as be of good conversation, and of truth, and by them shall you never be deceived nor repent you of.

Moreover, never follow your own wit in nowise, but in all your works, of such folks as I write of above, ask your advice and counsel, and doing thus, with the mercy of God, you shall do right well, and live in right much worship, and great heart's rest and ease.

And I will be to you as good lord and father as my heart can think.

And last of all, as heartily and as lovingly as ever father blessed his child in earth, I give you the blessing of Our Lord and of me, which of his infinite mercy increase you in all virtue and good living; and that your blood may by his grace from kindred to kindred multiply in this earth to his service, in such wise as after the departing from this wretched world here, you and they may glorify him eternally amongst his angels in heaven.

Written of mine hand,

The day of my departing from this land.

Your true and loving father

The following three years saw the near-complete loss of the English possessions in northern France (Rouen, Normandy etc.). Suffolk could not avoid taking the blame for these failures, partly because of the loss of Maine and Anjou through his marriage negotiations regarding Henry VI. When parliament met in November 1449, the opposition showed its strength by forcing the treasurer, Adam Moleyns, to resign.[1]

Moleyns was murdered by sailors at Portsmouth on 9 January 1450. Suffolk, realising that an attack on himself was inevitable, boldly challenged his enemies in parliament, appealing to the long and honourable record of his public services.[1] However, on 28 January he was arrested, imprisoned in the Tower of London and impeached in parliament by the Commons.

The King intervened to protect his favourite, who was banished for five years, but on his journey to Calais his ship was intercepted by the ship Nicholas of the Tower. Suffolk was captured, subjected to a mock trial, and executed by beheading.[6][7] His body was later found on the sands near Dover,[8] and was probably brought to a church in Suffolk, possibly Wingfield. He was interred in the Carthusian Priory in Hull by his widow Alice, as was his wish, and not in the church at Wingfield, as is often stated. The Priory, founded in 1377 by his grandfather the first Earl of Suffolk, was dissolved in 1539, and most of the original buildings did not survive the two Civil War sieges of Hull in 1642 and 1643.[9]

Feud with John Mowbray, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

From the 1430s until his death, de la Pole, who became increasingly powerful, both at court and in the region, was rivalled in East Anglia by John Mowbray, 3rd Duke of Norfolk.[10] Mowbray had enough political clout in the 1430s to control parliamentary representation in Suffolk,[11] but the local importance of the duke weakened his grasp. Mowbray clashed with de la Pole, and committed many illegalities doing so. These included damaging property of rivals, assaults, false allegations of outlawry (with confiscation of goods), and even murder.[12]

For Mowbray, East Anglia as the focus of his landed authority was forced upon him since this was where the majority of his estates were located.[13][12] He was then a newcomer to political society in the region,[13] and had to share influence with others.[14] By the time of his majority, de la Pole—with his links to central government and the King—was an established power in the region.[15] He hindered Mowbray's attempts at regional domination for over a decade,[16] leading to a feud that stretched from the moment Mowbray became Duke of Norfolk to the murder of de la Pole in 1450.[17] The feud was often violent, and led to fighting between their followers. In 1435, Robert Wingfield, Mowbray's steward of Framlingham, led a group of Mowbray retainers who murdered James Andrew, one of de la Pole's men. When local aldermen attempted to arrest Wingfield's party, the latter rained arrow fire upon the aldermen,[18] but Mowbray secured royal pardons for those responsible.[12]

By 1440, de la Pole was a royal favourite. He instigated Mowbray's imprisonment[10] on at least two occasions: in 1440 and in 1448.[19] The first saw him bound over for the significant amount of £10,000, and confined to living within the royal Household,[20] preventing him from returning to seek revenge in East Anglia.[10] Likewise, apart from an appointment to commissions of oyer and terminer in Norwich in 1443 (after the suppression of Gladman's Insurrection), he received no other significant offices or patronage from the crown. A recent biographer of Mowbray's, the historian Colin Richmond, has described this as Mowbray's "eclipse". De la Pole fought Mowbray with what one contemporary labelled "greet hevyng an shoving."[21]

Marriage and descendants

Suffolk was married on 11 November 1430 (date of licence), to (as her third husband) Alice Chaucer (1404–1475), daughter of Thomas Chaucer of Ewelme, Oxfordshire, and granddaughter of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer and his wife, Philippa Roet. In 1437, Henry VI licensed the couple to establish a chantry and almshouse for thirteen poor men at Ewelme, which they endowed with land at Ewelme and in Buckinghamshire, Hampshire and Wiltshire; the charitable trust continues to this day.[22]

Suffolk's only known legitimate son, John, became the second Duke of Suffolk in 1463. Suffolk also fathered an illegitimate daughter, Jane de la Pole.[23] Her mother is said to have been a nun, Malyne de Cay.

The nighte before that he was yolden [yielded himself up in surrender to the Franco-Scottish forces of Joan of Arc on 12 June 1429] he laye in bed with a nonne whom he toke oute of holy profession and defouled, whose name was Malyne de Cay, by whom he gate a daughter, now married to Stonard of Oxonfordshire.[24]

Jane de la Pole (died 28 February 1494) was married before 1450 to Thomas Stonor (1423–1474), of Stonor in Pyrton, Oxfordshire.

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Alice (1404–1475), daughter of Thomas Chaucer of Ewelme, Oxfordshire, married 11 November 1430 | |||

| John, 2nd Duke of Suffolk | 27 September 1442 | 1492 | Married 1st Lady Margaret Beaufort (no issue), 2nd Elizabeth of York (had issue) |

| By Malyne de Cay, nun and mistress | |||

| Jane de la Pole | c. Mar 1430 | 28 February 1494 | Married Thomas Stonor |

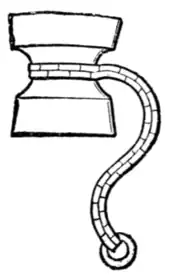

Jackanapes

Suffolk's nickname "Jackanapes" came from "Jack of Naples", a slang name for a monkey at the time. This was probably due to his heraldic badge, which consisted of an "ape's clog", i.e. a wooden block chained to a pet monkey to prevent it escaping.[25] The phrase "jackanape" later came to mean an impertinent or conceited person, due to the popular perception of Suffolk as a nouveau riche upstart; his great-grandfather had been a wool merchant from Hull.

Portrayals in drama, verse and prose

_MET_DP870115.jpg.webp)

- Suffolk is a major character in two Shakespeare plays. His negotiation of the marriage of Henry and Margaret is portrayed in Henry VI, Part 1. Shakespeare's version has Suffolk fall in love with Margaret. He negotiates the marriage so that he and she can be close to one another. His disgrace and death are depicted in Henry VI, Part 2. Shakespeare departs from the historical record by having Henry banish Suffolk for complicity in the murder of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. Suffolk is murdered by a pirate named Walter Whitmore (fulfilling a prophecy given earlier in the play proclaiming he will "die by Water"), and Margaret later wanders to her castle carrying his severed head and grieving.

- His murder is the subject of the traditional English folk ballad "Six Dukes Went a-Fishing" (Roud #78)

- Suffolk is the protagonist in Susan Curran's historical novel The Heron's Catch (1989).

- He plays a role in many of the seventeen Dame Frevisse detective novels of Margaret Frazer, set in England in the 1440s.

- Suffolk is a significant character in Cynthia Harnett's historical novel for children, The Writing on the Hearth (1971)

- Suffolk is one of the three dedicatees of Geoffrey Hill's sonnet sequence, "Funeral Music" (first published in Stand magazine; collected in King Log, Andre Deutsch 1968). Hill speculates about him in the essay appended to the poems.

- Suffolk is one of the main characters in Conn Iggulden's Wars of the Roses: Stormbird, about the end of the Hundred Years' War and the start of the Wars of the Roses.

See also

Footnotes

- Kingsford 1911, p. 27.

- Wagner 2006, p. 260.

- Britannica 1998.

- Bennett 1991, p. 24.

- Curran 2011, pp. 261–262.

- Hicks 2010, p. 68.

- Kingsford 1911.

- Davis 1999, letter 14, pp. 26–29.

- Page 1974, pp. 190–192.

- Richmond 2012.

- Crawford 2010, p. 14.

- Castor 2000, p. 108.

- Castor 2000, p. 105.

- Castor 2000, p. 56.

- Castor 2000, p. 114.

- Harriss 2005, p. 203.

- Virgoe 1980, p. 263.

- Virgoe 1980, p. 264.

- Griffiths 1981, p. 587.

- Castor 2000, p. 110.

- Castor 2000, p. 109.

- "History". The Ewelme Almshouse Charity. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- Richardson 2011, p. 359.

- HMC 1872, pp. 279–280.

- Fox-Davies 1909, p. 469.

References

- Bennett, Michael (23 May 1991). Agincourt 1415: Triumph against the odds. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-132-8.

- Britannica (20 July 1998). "William de la Pole, 1st duke of Suffolk". Encyclopædia Britannica.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Burke, J. (1835). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, 2. London: Henry Colburn.

- Davis, N., ed. (1999). The Paston Letters. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283640-3.

- Fox-Davies, A. C. (1909). . London: T.C. & E.C. Jack.

- Hicks, M. (2010). The Wars of the Roses. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11423-2.

- HMC (1872). Third Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. London: Stationery Office. OCLC 223375408.

- Kingsford, C. L. (1896). "Pole, William de la, fourth Earl and first Duke of Suffolk (1396–1450)". Sidney Lee, ed. Dictionary of National Biography. 46. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge (1911). "Suffolk, William de la Pole, Duke of". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–28.

- Page, W., ed. (1974). A History of the County of York: Volume 3. Victoria County History.

- Richardson, D. (2011). Kimball G. Everingham (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4609-9270-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wagner, J. A. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0.

- Watts, J. (2004). "Pole, William de la, first duke of Suffolk (1396–1450)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22461. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Bibliography

- Castor, H. (2000). The King, the Crown, and the Duchy of Lancaster: Public Authority and Private Power, 1399–1461. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820622-4.

- Crawford, A. (2010). Yorkist Lord: John Howard, Duke of Norfolk c. 1425–1485. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-44115-201-5.

- Curran, Susan (2011). The English Friend. Norwich: Lasse Press. ISBN 978-0-9568758-0-8.

- Fryde, E. B. (1964). The Wool Accounts of William de la Pole: a study of some aspects of the English wool trade at the start of the Hundred Years' War. St. Anthony's Press, Borthwick Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 978-0-900701-26-9.

- Griffiths, R. A. (1981). The Reign of King Henry VI. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04372-5.

- Harriss, G. L. (2005). Shaping the Nation: England 1360-1461. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921119-7.

- Richardson, Douglas (2004). Kimball G. Everingham (ed.). Plantagenet Ancestry. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8063-1750-2.

- Richmond, Colin (2012) [2004]. "Mowbray, John, third duke of Norfolk (1415–1461)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19454. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Watts, J. (1996). Henry VI and the Politics of Kingship. Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-42039-6.

- Virgoe, R. (1980). "The murder of James Andrew: Suffolk faction in the 1430s". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute OfArchaeology and History. 34: 263–268. OCLC 679927444.

- Williams, E. T.; Nicholls, C. S., eds. (1981). Dictionary of National Biography (8th supplement). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-865207-6.