William Tasker (poet)

William Tasker (1740–1800) was an English clergyman, scholar and poet. He made translations of works of Pindar and Horace. His own poems celebrated the "genius of Britain", which to him was both artistic and military. He was also interested in science, including physiognomy.

William Tasker | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1740 Iddesleigh, Devon, England |

| Died | 1800 Iddesleigh, Devon, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation(s) | Anglican priest, poet, antiquary |

| Known for | Ode to the Warlike Genius of Great Britain |

Life

William Tasker was born in 1740 at Iddesleigh, Devon.[1] He was the only son of William Tasker (1708–1772) and Jane Vickries (died 1795). His father was rector of Iddesleigh, Devonshire, from 6 July 1738.[2] He was educated at Barnstaple, then attended Exeter College, Oxford, matriculating on 20 February 1758. He remained there as sojourner and obtained a B.A. on 2 February 1762. On 24 June 1764, he was ordained deacon, and next day was made curate of Monk-Okehampton, near Iddesleigh. He was ordained a priest on 12 July 1767.[2]

Tasker became rector of Iddesleigh on 6 November 1772, after his father died. Tasker was a friend of Dr. William Hunter, attended his lectures, and studied botany in the gardens at Kew. James Boswell describes a meeting between Tasker and Samuel Johnson on 16 March 1779, where Tasker asked for Johnson's opinion of his poems. Boswell wrote, "The bard was a lank, bony figure, with short black hair; he was writhing himself in agitation while Johnson read, and, showing his teeth in a grin of earnestness, exclaimed in broken sentences and in a keen, sharp tone, 'Is that poetry, sir—is it Pindar?'". Isaac D'Israeli later said this description was true.[2] Tasker was an admirer of the poet Mary Robinson (1757–1800), whom he praised as the "Sweet Sappho of our Isle."[3]

Tasker was careless with his finances. The revenues of his benefice were placed under sequestration on 23 March 1780. He said that his "unletter'd brother-in-law" had obtained the sequestration in an "illegal mode" through "merciless and severe persecutions and litigations". His brother-in-law had died by 1790.[2] Writing to Gough Nichols, editor of the Gentleman's Magazine in 1797, Tasker said he was "confined in my dreary situation at Starvation-Hall, 40 miles below Exeter, out of the verge of Literature & where even your extensive magazine has never yet reached."[4]

William Tasker died after a long and painful illness at Iddesleigh rectory on 4 February 1800.[2] At the time of his death he was working on a history of physiognomy from Aristotle to Lavater.[5] He was buried near the chancel of the Church of St James, Iddesleigh. A tablet was erected on the north wall of the church tower. His widow, Eleonora, died at Exbourne on 2 January 1801, aged 56, and was buried in the same grave with her husband. They had no children.[2]

Work and reception

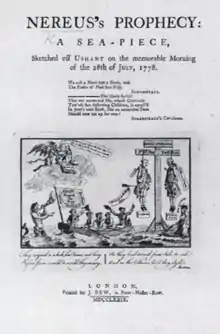

Tasker thought the results of the Seven Years' War (1754–63) had only been the growth of corruption and luxury at home.[6] He wrote several poems on the Anglo-French War (1778–83) in which he represented the Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, as being at the centre of a selfish and corrupt network.[7] Tasker saw the action by Admiral Augustus Keppel at the Battle of Ushant as a great victory, which he celebrated in his poem Nereus's Prophecy: A Sea-Piece Sketched off Ushant (1779).[7] The cover of this poem has a cartoon in which Sandwich and Hugh Palliser are showing hanging from a gallows, laden with emblems that show they are guilty, while a seated courtesan weeps over their fate.[8] In A congratulatory Ode to Admiral Keppel (1779) he wrote of Keppel, whom he saw as representing the interests of the honest trading community in England,

This Keppel knew; yet stepp'd he forth

Conscious of Honesty and Worth:

He saw, he fought, he led

His squadron on – though disobey'd,

He never dream'd he was betray'd,

Or trembled for his Head.[6]

In his Elegy on the Death of David Garrick (1779) Tasker celebrates the artistic genius of Garrick, Shakespeare and Reynolds, and implicitly links it to the warlike genius of the nation.[9] In his Ode to the Warlike Genius of Great Britain (1780) he urged Britain to wake up and defeat the aggressors.[10] The ‘Ode to the Warlike Genius' was dedicated to Lord Amherst. Some new stanzas were spoken before the king at Weymouth.[11] The Gentleman's Magazine said the poem was "well-calculated to rouse the martial spirit of the nation".[7] He complemented the Duchess of Devonshire in the poem for wearing riding dress at the Cox-heath military camp, calling her the "Genius of Britain".[12]

The Gentleman's magazine called Tasker's play Arviragus, a Tragedy (1796), written during the French Revolution, a "bold attempt towards a national drama", and pointed out the contemporary relevance,[13]

the British king Aviragus, the principal character, is represented to be a gallant warrior and a patriot-king, reigning over a free and warlike people; and both are represented as uniting their utmost efforts to resist foreign invasion. ... we are particularly pleased with the songs, or rather little odes, of the Bard; and the war song, which he recites to the military at large, when they are at the point of engaging with the Romans, is every way worthy of the author of the Ode to the Warlike Genius of Great Britain."[13]

The Gentleman's Magazine quoted The War-Song of Clewillin, The British Bard in March 1797. The poem called on the soldiers to "Rush on the foe without dismay, | Like roaring lions on their prey." In the years that followed the magazine would praise Tasker's work as "so well calculated to animate loyal Britons against invaders, and to inspire the necessary unanimity and concord ... exceedingly well adapted to the present times; since it breathes a three-fold spirit of Poetry, Loyalty, and Patriotism." the Gentleman's Magazine serialised the 1780 Ode to the Warlike Genius of Great Britain over nine editions from December 1798 to August 1799. In the poem, Tasker says the role of the divinely inspired bards is to "Inspire the sons of Mars in dreams, | And fire their souls in warlike themes."[14]

Publications

Tasker's published works included:[11]

- Tasker, William (1778), Ode to the Warlike Genius of Great Britain. 2nd edition 1779, 3rd edition with other poems, 1779. Anonymous.

- The most important of the other poems was An Ode to Curiosity: a Bath-Easton Amusement (2nd edition 1779), which had been previously published as "by Impartialist."

- Horace (1779), Carmen Seculare of Horace, translated into English verse. Anonymous

- Tasker, William (1779), Congratulatory Ode to Admiral Keppell. Anonymous

- Elegy on the Death of David Garrick, 1779. 2nd edition, with additions, 1779. Anonymous

- Tasker, William (1780), An Ode to the Memory of the Right Reverend Thomas Wilson, late Lord Bishop of Sodor and Man. Reproduced in the bishop's works (1781 edition), volume i. pp. cxxxi–iv.

- Ode to Speculation: a poetical Amusement for Bath Easton, 1780

- Select Odes of Pindar and Horace translated. With original poems and notes, vol. 1 volume, 1780. 2nd edition in 3 volumes. 1790–3

- Most of Tasker's published poems were reproduced in this edition, which also included letters on the anatomy of Homer.

- Tasker, William (1783), Annus Mirabilis, or the Eventful Year 1782

- Tasker, William (1794), A series of letters [chiefly on the wounds and deaths in the 'Iliad,' 'Æneid,' and 'Pharsalia']. 2nd edition 1798

- Arviragus: a Tragedy, 2nd edition 1798, 1796

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link). Twice performed in March 1797 at the Exeter Theatre. - Extracts from Tasker's naval and military poems, Bath, 1799

Notes

- Cooke 1817, p. 65.

- Courtney 1898, p. 373.

- Robinson 2011, p. 236.

- Williamson 2016, p. 55.

- Courtney 1898, p. 374.

- Jones 2011, p. 141.

- Jones 2011, p. 140.

- McCreery 2004, p. 96.

- O'Quinn 2011, p. 223.

- O'Quinn 2011, p. 222.

- Courtney 1898, p. 374–375.

- McCreery 2004, p. 142.

- Bainbridge 2003, p. 52.

- Bainbridge 2003, p. 53.

Sources

- Bainbridge, Simon (2003), British Poetry and the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars: Visions of Conflict, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-818758-5, retrieved 24 August 2016

- Cooke, George Alexander (1817), Topographical and Statistical Description of the County of Devon;: Containing an Account of Its Situation, Extent, ..., Printed, by assignment from the executors of the late C. Cooke, for Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, retrieved 24 August 2016

- Courtney, William Prideaux (1898), "Tasker, William", Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, vol. 55, retrieved 24 August 2016

- Jones, Robert W. (22 September 2011), Literature, Gender and Politics in Britain During the War for America, 1770-1785, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-00789-5, retrieved 24 August 2016

- McCreery, Cindy (2004), The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-century England, Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19-926756-9, retrieved 24 August 2016

- O'Quinn, Daniel (6 May 2011), Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium, 1770–1790, JHU Press, ISBN 978-1-4214-0189-8, retrieved 24 August 2016

- Robinson, D. (28 March 2011), The Poetry of Mary Robinson: Form and Fame, Palgrave Macmillan US, ISBN 978-0-230-11803-4, retrieved 24 August 2016

- Williamson, Gillian (27 January 2016), British Masculinity in the 'Gentleman's Magazine', 1731 to 1815, Palgrave Macmillan UK, ISBN 978-1-137-54233-5, retrieved 24 August 2016