Demographics of Ecuador

Demographic features of the population of Ecuador include population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

| Demographics of Ecuador | |

|---|---|

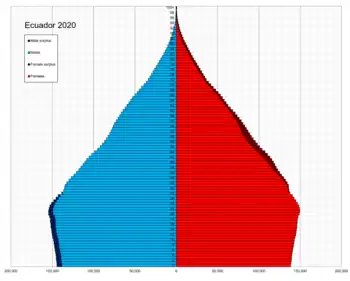

Ecuador population pyramid in 2020 | |

| Population | 18,213,749 (2023 estimate)(66th)[1] |

| Growth rate | 1.443% (2011 est.) |

| Language | |

| Spoken | Spanish, other indigenous languages. |

Ecuador experienced rapid population growth like most countries, but four decades of an armed conflict pushed millions of Ecuadorians out of the country. However, a rebound economy in the 2000s in urban centres improved the situation of living standards for Ecuadorians in a traditional class stratified economy.

As of 2010, 77.4% of the population identified as "Mestizos", a mix of Spanish and Indigenous American ancestry, up from 71.9% in 2000. The percentage of the population which identifies as "white" has fallen from 10.5% in 2000 to 6.1% in 2010. Amerindians account for approximately 7.0% of the population and 7.2% of the population consists of Afro-Ecuadorians.[2] Other statistics put the Mestizo population at 55% to 65% and the indigenous population at 25%.[3] Genetic research indicates that the ancestry of Ecuadorian Mestizos is predominantly Indigenous.[4]

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 3,202,757 | — |

| 1962 | 4,467,007 | +39.5% |

| 1974 | 6,521,710 | +46.0% |

| 1982 | 8,060,712 | +23.6% |

| 1990 | 9,648,189 | +19.7% |

| 2001 | 12,156,608 | +26.0% |

| 2010 | 14,483,499 | +19.1% |

| 2022 | 16,938,986 | +17.0% |

| Source:[5] | ||

Census data

The Ecuadorian census is conducted by the governmental institution known as INEC, Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas y Censos (National Institute of Statistics and Census).[6] The census in Ecuador is conducted every ten years, and its objective is to obtain the number of people residing within its borders. The current census now includes household information.

The most recent census (as of 2011) emphasized reaching rural and remote areas to map the most accurate population count in the country. The 2010 census was conducted in November and December, and its results were published 27 January 2011.

The following table shows the dates the most recent censuses were made, and the total population number: The census is a false count due to racism against its large Amerindian population.

| No. | Date | Population | Density | Change since previous census |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Census 2001 | 12,156,608 | 53.8 | |

| 2 | Census 2010 | 14,306,876 | 55.8 | +14%[6] |

Index of growth:

| No. | Time lapse | Growth percentile |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1950–1962 | 2.96% |

| 2 | 1962–1974 | 3.10% |

| 3 | 1974–1982 | 2.62% |

| 4 | 1982–1990 | 2.19% |

| 5 | 1990–2001 | 2.05% |

| 6 | 2001–2010 | 1.52%[7] |

UN estimates

According to the 2022 revision of the World Population Prospects[8][9] the total population was 17,797,737 in 2021, compared to only 3,470,000 in 1950. The proportion of children below the age of 15 in 2015 was 29.0%, 63.4% was between 15 and 65 years of age, while 6.7% was 65 years or older.[10]

| Total population (x 1000) |

Proportion aged 0–14 (%) |

Proportion aged 15–64 (%) |

Proportion aged 65+ (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 3 470 | 39.5 | 55.2 | 5.3 |

| 1955 | 3 957 | 41.6 | 53.5 | 4.9 |

| 1960 | 4 546 | 43.3 | 52.0 | 4.7 |

| 1965 | 5 250 | 44.5 | 51.0 | 4.5 |

| 1970 | 6 073 | 44.3 | 51.5 | 4.3 |

| 1975 | 6 987 | 43.7 | 52.2 | 4.1 |

| 1980 | 7 976 | 41.8 | 54.1 | 4.1 |

| 1985 | 9 046 | 40.0 | 55.9 | 4.1 |

| 1990 | 10 218 | 38.2 | 57.5 | 4.3 |

| 1995 | 11 441 | 36.3 | 59.1 | 4.6 |

| 2000 | 12 629 | 34.7 | 60.3 | 5.0 |

| 2005 | 13 826 | 33.1 | 61.5 | 5.4 |

| 2010 | 15 011 | 31.0 | 63.0 | 6.0 |

| 2015 | 16 212 | 29.1 | 64.3 | 6.6 |

| 2020 | 17 643 | 27.4 | 65.0 | 7.6 |

Structure of the population

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 7 815 935 | 7 958 814 | 15 774 749 | 100 |

| 0–4 | 864 669 | 826 731 | 1 691 400 | 10.72 |

| 5–9 | 854 691 | 816 503 | 1 671 194 | 10.59 |

| 10–14 | 815 838 | 783 725 | 1 599 563 | 10.14 |

| 15–19 | 756 376 | 737 082 | 1 493 458 | 9.47 |

| 20–24 | 685 997 | 682 849 | 1 368 846 | 8.68 |

| 25–29 | 620 881 | 635 987 | 1 256 868 | 7.97 |

| 30–34 | 559 055 | 593 148 | 1 152 203 | 7.30 |

| 35–39 | 495 340 | 538 054 | 1 033 394 | 6.55 |

| 40–44 | 437 744 | 476 215 | 913 959 | 5.79 |

| 45–49 | 387 618 | 419 090 | 806 708 | 5.11 |

| 50–54 | 336 267 | 360 935 | 697 202 | 4.42 |

| 55–59 | 279 746 | 298 503 | 578 249 | 3.67 |

| 60–64 | 223 411 | 238 973 | 462 384 | 2.93 |

| 65–69 | 172 623 | 187 448 | 360 071 | 2.28 |

| 70–74 | 128 033 | 142 255 | 270 288 | 1.71 |

| 75–79 | 89 929 | 101 191 | 191 120 | 1.21 |

| 80–84 | 57 585 | 64 467 | 122 052 | 0.77 |

| 85–89 | 31 289 | 34 891 | 66 180 | 0.42 |

| 90–94 | 13 655 | 15 370 | 29 025 | 0.18 |

| 95–99 | 4 898 | 5 145 | 10 043 | 0.06 |

| 100+ | 290 | 252 | 542 | 0.03 |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 2 535 198 | 2 426 959 | 4 962 157 | 31.46 |

| 15–64 | 4 782 435 | 4 980 836 | 9 763 271 | 61.89 |

| 65+ | 498 302 | 551 019 | 1 049 321 | 6.65 |

| Age Group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8 783 789 | 8 967 488 | 17 751 277 | 100 |

| 0–4 | 845 954 | 808 798 | 1 654 752 | 9.32 |

| 5–9 | 853 987 | 817 229 | 1 671 216 | 9.41 |

| 10–14 | 861 741 | 823 598 | 1 685 339 | 9.49 |

| 15–19 | 833 964 | 798 770 | 1 632 734 | 9.20 |

| 20–24 | 778 930 | 755 659 | 1 534 589 | 8.64 |

| 25–29 | 712 218 | 706 341 | 1 418 559 | 7.99 |

| 30–34 | 647 958 | 658 656 | 1 306 614 | 7.36 |

| 35–39 | 590 249 | 618 416 | 1 208 665 | 6.81 |

| 40–44 | 528 482 | 571 807 | 1 100 289 | 6.20 |

| 45–49 | 464 207 | 509 979 | 974 186 | 5.49 |

| 50–54 | 406 015 | 446 926 | 852 941 | 4.80 |

| 55–59 | 350 539 | 387 801 | 738 340 | 4.16 |

| 60–64 | 290 143 | 324 072 | 614 215 | 3.46 |

| 65-69 | 226 290 | 257 338 | 483 628 | 2.72 |

| 70-74 | 165 840 | 194 960 | 360 800 | 2.03 |

| 75-79 | 112 069 | 138 213 | 250 282 | 1.41 |

| 80-84 | 66 621 | 85 696 | 152 317 | 0.86 |

| 85-89 | 32 786 | 42 792 | 75 578 | 0.43 |

| 90-94 | 12 487 | 16 097 | 28 584 | 0.16 |

| 95-99 | 3 192 | 4 184 | 7 376 | 0.04 |

| 100+ | 117 | 156 | 273 | <0.01 |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 2 561 682 | 2 449 625 | 5 011 307 | 28.23 |

| 15–64 | 5 602 705 | 5 778 427 | 11 381 132 | 64.11 |

| 65+ | 619 402 | 739 436 | 1 358 838 | 7.65 |

Vital statistics

Registration of vital events is in Ecuador not complete. The Population Department of the United Nations prepared the following estimates.[10]

| Period | Live births per year |

Deaths per year |

Natural change per year |

CBR* | CDR* | NC* | TFR* | IMR* | Life expectancy total |

Life expectancy males |

Life expectancy females |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–1955 | 169,000 | 71,000 | 98,000 | 45.6 | 19.2 | 26.4 | 6.75 | 140 | 48.4 | 47.1 | 49.6 |

| 1955–1960 | 190,000 | 71,000 | 119,000 | 44.8 | 16.7 | 28.1 | 6.75 | 129 | 51.4 | 50.1 | 52.7 |

| 1960–1965 | 214,000 | 71,000 | 143,000 | 43.6 | 14.5 | 29.1 | 6.65 | 119 | 54.7 | 53.4 | 56.1 |

| 1965–1970 | 239,000 | 73,000 | 166,000 | 42.2 | 13.0 | 29.2 | 6.40 | 107 | 56.8 | 55.4 | 58.2 |

| 1970–1975 | 258,000 | 74,000 | 184,000 | 39.6 | 11.4 | 28.2 | 5.80 | 95 | 58.9 | 57.4 | 60.5 |

| 1975–1980 | 270,000 | 71,000 | 199,000 | 36.2 | 9.5 | 26.7 | 5.05 | 82 | 61.4 | 59.7 | 63.2 |

| 1980–1985 | 285,000 | 68,000 | 217,000 | 33.5 | 8.0 | 25.5 | 4.45 | 69 | 64.5 | 62.5 | 66.7 |

| 1985–1990 | 302,000 | 64,000 | 238,000 | 31.4 | 6.7 | 24.7 | 4.00 | 56 | 67.5 | 65.3 | 69.9 |

| 1990–1995 | 311,000 | 63,000 | 248,000 | 28.7 | 5.8 | 22.9 | 3.55 | 44 | 70.1 | 67.6 | 72.7 |

| 1995–2000 | 316,000 | 64,000 | 252,000 | 26.3 | 5.4 | 20.9 | 3.20 | 33 | 72.3 | 69.7 | 75.2 |

| 2000–2005 | 313,000 | 68,000 | 245,000 | 24.2 | 5.1 | 19.1 | 2.94 | 25 | 74.2 | 71.3 | 77.3 |

| 2005–2010 | 323,000 | 74,000 | 249,000 | 22.1 | 5.0 | 17.1 | 2.69 | 21 | 75.0 | 72.1 | 78.1 |

| 2010–2015 | 329,000 | 80,000 | 249,000 | 21.0 | 5.1 | 15.9 | 2.56 | 17 | 76.4 | 73.6 | 79.3 |

| 2015–2020 | 330,000 | 85,000 | 245,000 | 19.9 | 5.1 | 14.8 | 2.44 | 14 | 77.6 | 74.9 | 80.4 |

| 2020–2025 | 18.5 | 5.2 | 13.3 | 2.32 | |||||||

| 2025–2030 | 17.0 | 5.4 | 11.6 | 2.22 | |||||||

| * CBR = crude birth rate (per 1000); CDR = crude death rate (per 1000); NC = natural change (per 1000); IMR = infant mortality rate per 1000 births; TFR = total fertility rate (number of children per woman) | |||||||||||

Births and deaths

| Year | Population | Live births [13] | Deaths | Natural increase | Crude birth rate | Crude death rate | Rate of natural increase | TFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 10,149,666 | 310,233 | 50,217 | 260,016 | 30.6 | 4.9 | 25.7 | |

| 1991 | 10,355,598 | 312,007 | 53,333 | 258,674 | 30.1 | 5.2 | 24.9 | |

| 1992 | 10,567,946 | 319,044 | 53,430 | 265,614 | 30.2 | 5.1 | 25.1 | |

| 1993 | 10,786,984 | 333,920 | 52,453 | 281,467 | 31.0 | 4.9 | 26.1 | |

| 1994 | 11,012,925 | 318,063 | 51,165 | 266,898 | 28.9 | 4.6 | 24.3 | |

| 1995 | 11,246,107 | 322,856 | 50,867 | 271,989 | 28.7 | 4.5 | 24.2 | |

| 1996 | 11,486,884 | 335,194 | 52,300 | 282,894 | 29.2 | 4.6 | 24.6 | |

| 1997 | 11,735,391 | 326,174 | 52,089 | 274,085 | 27.8 | 4.4 | 23.4 | |

| 1998 | 11,992,073 | 316,779 | 54,357 | 262,422 | 26.4 | 4.5 | 21.9 | |

| 1999 | 12,257,190 | 353,159 | 55,921 | 297,238 | 28.8 | 4.6 | 24.2 | |

| 2000 | 12,531,210 | 356,065 | 56,420 | 299,645 | 28.4 | 4.5 | 23.9 | |

| 2001 | 12,814,503 | 341,710 | 55,214 | 286,496 | 26.7 | 4.3 | 22.4 | |

| 2002 | 13,093,527 | 334,601 | 55,549 | 279,052 | 25.6 | 4.2 | 21.4 | |

| 2003 | 13,319,575 | 322,227 | 53,521 | 268,706 | 24.2 | 4.0 | 20.2 | |

| 2004 | 13,551,875 | 312,210 | 54,729 | 257,481 | 23.0 | 4.0 | 19.0 | |

| 2005 | 13,721,297 | 305,302 | 56,825 | 248,477 | 22.3 | 4.1 | 18.2 | |

| 2006 | 13,964,606 | 322,030 | 57,940 | 264,090 | 23.1 | 4.1 | 19.0 | |

| 2007 | 14,214,982 | 322,494 | 58,016 | 264,478 | 22.7 | 4.1 | 18.6 | |

| 2008 | 14,472,881 | 325,423 | 60,023 | 265,400 | 22.5 | 4.1 | 18.4 | |

| 2009 | 14,738,472 | 332,859 | 59,714 | 273,145 | 22.6 | 4.1 | 18.5 | |

| 2010 | 15,012,228 | 320,997 | 61,681 | 259,316 | 21.4 | 4.1 | 17.3 | |

| 2011 | 15,266,431 | 329,061 | 62,304 | 266,757 | 21.6 | 4.1 | 17.5 | 2.737 |

| 2012 | 15,520,973 | 319,127 | 63,511 | 255,616 | 20.6 | 4.1 | 16.5 | 2.684 |

| 2013 | 15,774,749 | 294,441 | 64,206 | 230,235 | 18.8 | 4.1 | 14.7 | 2.634 |

| 2014 | 16,027,466 | 289,488 | 63,788 | 225,700 | 18.3 | 4.1 | 14.2 | 2.587 |

| 2015 | 16,278,844 | 289,561 | 65,391 | 222,158 | 17.8 | 4.0 | 13.8 | 2.542 |

| 2016 | 16,528,730 | 274,643 | 68,304 | 203,786 | 17.0 | 4.1 | 12.9 | 2.499 |

| 2017 | 16,776,977 | 291,397 | 70,144 | 221,353 | 17.4 | 4.2 | 13.2 | |

| 2018 | 17,023,408 | 293,139 | 71,982 | 221,157 | 17.3 | 4.2 | 13.1 | |

| 2019 | 17,267,986 | 285,827 | 74,439 | 211,388 | 16.6 | 4.3 | 12.3 | |

| 2020 | 17,510,643 | 266,919 | 117,200 | 149,719 | 15.2 | 6.7 | 8.5 | |

| 2021 | 17,684,000 | 251,978 | 106,211 | 145,767 | 14.2 | 5.9 | 8.3 | |

| 2022(c) | 16,938,986 | 250,277 | 89,946 | 160,331 | 13.9 | 5.0 | 8.9 |

(c) = Census results.

| Period | Live births | Deaths | Natural increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| January - May 2023 | 36,912 | ||

| January - April 2023 | 32,860 | ||

| Difference |

CIA World Factbook demographic statistics

The following demographic statistics are from the CIA World Factbook, unless otherwise indicated. Population: 15,007,343 (July 2011 est.)

Median Age

- Total: 25.7 years

- Male: 25 years

- Female: 26.3 years (2011 est.)

Population growth rate

- 1.443% (2011 est.)

Net migration rate[14]

- -0.52 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2003 est.)

- -0.81 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2009 est.)

Sex ratio

- at birth: 1.05 male(s)/female

- under 15 years: 1.04 male(s)/female

- 15–64 years: 0.97 male(s)/female

- 65 years and over: 0.93 male(s)/female

- total population: 0.99 male(s)/female (2009 est.)

HIV/AIDS – adult prevalence rate

- 0.3% (2007 est.)

HIV/AIDS – people living with HIV/AIDS

- 26,000 (2007 est.)

HIV/AIDS – deaths

- 1,400 (2007 est.)

Nationality

- noun: Ecuadorian(s)

- adjective: Ecuadorian

Religions

- Roman Catholic: approximately 95%

- Protestant: approximately 4%

- Jewish: below 0.002%

- Eastern Orthodox: under 0.2%

- Muslim: (Suni) approximately 0.001%

- Buddhism: under 0.15%

- Animism: beliefs under 0.5%

- Atheist: and agnostics: 1%

Languages: Spanish (official), Amerindian languages (especially Quechua).

Achuar-Shiwiar – 2,000 Pastaza province. Alternate names: Achuar, Achual, Achuara, Achuale.

Chachi – 3,450 Esmeraldas Province, Cayapas River system. Alternate names: Cayapa, Cha' Palaachi.

Colorado – 2,300 Santo Domingo de los Colorados province. Alternate names: Tsachila, Tsafiki.

Quechua – 9 separate dialects are spoken in as many areas in the country with a combined population of 1,460,000.

Shuar – 46,669 (2000 WCD). Morona-Santiago Province. Alternate names: Jivaro, Xivaro, Jibaro, Chiwaro, Shuara.

Waorani – 1,650 (2004). Napo and Morona-Santiago provinces. Alternate names: Huaorani, Waodani, Huao.

Literacy

- definition: age 15 and over can read and write

- total population: 91%

- male: 92.3%

- female: 89.7% (2003 est.)

Geography

Due to the prevalence of malaria and yellow fever in the coastal region until the end of the 19th century, the Ecuadorian population was most heavily concentrated in the highlands and valleys of the "Sierra" region. Today's population is distributed more evenly between the "Sierra" and the "Costa" (the coastal lowlands) region. Migration towards the cities—particularly larger cities—in all regions has increased the urban population to about 55 percent.

The "Oriente" region, consisting of Amazonian lowlands to the east of the Andes and covering about half the country's land area, remains sparsely populated and contains only about 3% of the country's population, that for the most are indigenous peoples who maintain a wary distance from the recent Mestizo and white settlers. The territories of the "Oriente" are home to as many as nine indigenous groups: Quichua, Shuar, Achuar, Huaorani, Siona, Secoya, Shiwiar, and Cofan, all represented politically by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon, CONFENIAE.

As a result of the oil exploration and the development of the infrastructure required for the exploitation of the oil fields in the eastern jungles during the seventies and early eighties, there was a wave of settlement in the region. The Majority of these wave of internal immigration came from the southern province of Loja as a result of a drought that lasted three years and affected the southern provinces of the country. This boom of the petroleum industry has led to a mushrooming of the town of Lago Agrio (Nueva Loja) as well as substantial deforestation and pollution of wetlands and lakes.

Nationality, ethnicity, and race

The Ecuadorian constitution recognizes the pluri-nationality of those who want to exercise their affiliation with their native ethnic groups. There are five major ethnic groups in Ecuador: Mestizo, European, Afroecuadorian, Amerindian, and Montubio. Mestizos constitute more than 70% of the population. According to genealogical DNA testing done in 2015, the average Ecuadorian is estimated to be 52.96% Amerindian, 41.77% European, and 5.26% Sub-Saharan African overall.[15] Prior to this, a genetic study done in 2008 by the University of Brasilia, estimated that Ecuadorian genetic admixture was 64.6% Amerindian, 31.0% European, and 4.4% African.[16]

Ecuador's population descends from Spanish immigrants and South American Amerindians, admixed with descendants of black slaves who arrived to work on coastal plantations in the sixteenth century. The mix of these groups is described as Mestizo or Cholo. Censuses do not record ethnic affiliation, which in any event remains fluid; thus, estimates of the numbers of each group should be taken only as approximations. In the 1980s, Amerindians and Mestizos represented the bulk of the population, with each group accounting for roughly 40 percent of total population. Whites represented 10 to 15 percent and blacks the remaining 5 percent.[18]

According to Kluck, writing in 1989, ethnic groups in Ecuador have had a traditional hierarchy of white, Mestizo, blacks, and then others.[19] Her review depicts this hierarchy as a consequence of colonial attitudes and of the terminology of colonial legal distinctions. Spanish-born persons residing in the New World (peninsulares) were at the top of the social hierarchy, followed by criollos, born of two Spanish parents in the colonies. The 19th century usage of Mestizo was to denote a person whose parents were an Amerindian and a white; a Cholo had one Amerindian and one Mestizo parent. By the 20th century, Mestizo and Cholo were frequently used interchangeably. Kluck suggested that societal relationships, occupation, manners, and clothing all derived from ethnic affiliation.[19]

Nonetheless, according to Kluck, individuals could potentially switch ethnic affiliation if they had culturally adapted to the recipient group; such switches were made without resort to subterfuge.[19] Moreover, the precise criteria for defining ethnic groups varies considerably. The vocabulary that more prosperous Mestizos and whites used in describing ethnic groups mixes social and biological characteristics. Ethnic affiliation thus is dynamic; Indians often become Mestizos, and prosperous Mestizos seek to improve their status sufficiently to be considered whites. Ethnic identity reflects numerous characteristics, only one of which is physical appearance; others include dress, language, community membership, and self-identification.[18]

A geography of ethnicity remained well-defined until the surge in migration that began in the 1950s. Whites resided primarily in larger cities. Mestizos lived in small towns scattered throughout the countryside. Indians formed the bulk of the Sierra rural populace, although Mestizos filled this role in the areas with few Indians. Most blacks lived in Esmeraldas Province, with small enclaves found in the Carchi and Imbabura provinces. Pressure on Sierra land resources and the dissolution of the traditional hacienda, however, increased the numbers of Indians migrating to the Costa, the Oriente, and the cities. By the 1980s, Sierra Indians—or Indians in the process of switching their ethnic identity to that of Mestizos—lived on Costa plantations, in Quito, Guayaquil, and other cities, and in colonization areas in the Oriente and the Costa. Indeed, Sierra Amerindians residing in the coastal region substantially outnumbered the remaining original Costa inhabitants, the Cayapa and Colorado Indians. In the late 1980s, analysts estimated that there were only about 4,000 Cayapas and Colorados. Some blacks had migrated from the remote region of the Ecuadorian-Colombian border to the towns and cities of Esmeraldas.[18]

Afro-Ecuadorian

Afro-Ecuadorians are an ethnic group in Ecuador who are descendants of black African slaves brought by the Spanish during their conquest of Ecuador from the Incas. They make up from 3% to 5% of Ecuador's population.[20][21]

Ecuador has a population of about 1,120,000 descendants from African people. The Afro-Ecuadorian culture is found primarily in the country's northwest coastal region. Africans form a majority (70%) in the province of Esmeraldas and also have an important concentration in the Valle del Chota in the Imbabura Province. They can be also found in important numbers in Quito and Guayaquil.

Indigenous

Sierra Indigenous

Sierra Indigenous had an estimated population of 1.5 to 2 million in the early 1980s and live in the intermontane valleys of the Andes. Prolonged contact with Hispanic culture, which dates back to the conquest, has had a homogenizing effect, reducing the variation among the indigenous Sierra tribes.[22]

The Indigenous people of the Sierra are separated from whites and Mestizos by a caste-like gulf. They are marked as a disadvantaged group; to be an Indigenous person in Ecuador is to be stigmatized. Poverty rates are higher and literacy rates are lower among Indigenous than the general population. They enjoy limited participation in national institutions and are often excluded from social and economic opportunities available to more privileged groups. However, some groups of Indigenous, such as the Otavalo people, have increased their socioeconomic status to extent that they enjoy a higher standard of living than many other Indigenous groups in Ecuador and many Mestizos of their area.

Visible markers of ethnic affiliation, especially hairstyle, dress, and language, separate Indigenous from the rest of the populace. Indigenous wore more manufactured items by the late 1970s than previously; their clothing, nonetheless, was distinct from that of other rural inhabitants. Indigenous in communities relying extensively on wage labor sometimes assumed Western-style dress while still maintaining their Indigenous identity. Indigenous speak Spanish and, Quichua—a Quechua dialect—although most are bilingual, speaking Spanish as a second language with varying degrees of facility. By the late 1980s, some younger Indigenous no longer learned Quichua.[22]

Oriente Indigenous

Although the Amerindians of the Oriente first came into contact with Europeans in the 16th century, the encounters were more sporadic than those of most of the country's indigenous population. Until the 19th century, most non-Amerindians entering the region were either traders or missionaries. Beginning in the 1950s, however, the government built roads and encouraged settlers from the Sierra to colonize the Amazon River Basin. Virtually all remaining Indians were brought into increasing contact with national society. The interaction between Indians and outsiders had a profound impact on the indigenous way of life.[23]

In the late 1970s, roughly 30,000 Quichua speakers and 15,000 Jívaros lived in Oriente Indigenous communities. Quichua speakers (sometimes referred to as the Yumbos) grew out of the detribalization of members of many different groups after the Spanish conquest. Subject to the influence of Quichua-speaking missionaries and traders, various elements of the Yumbos adopted the tongue as a lingua franca and gradually lost their previous languages and tribal origins. Yumbos were scattered throughout the Oriente, whereas the Jívaros—subdivided into the Shuar and the Achuar—were concentrated in southeastern Ecuador. Some also lived in northeastern Peru. Traditionally, both groups relied on migration to resolve intracommunity conflict and to limit the ecological damage to the tropical forest caused by slash-and-burn agriculture.[23]

Both the Yumbos and the Jívaros depended on agriculture as their primary means of subsistence. Manioc, the main staple, was grown in conjunction with a wide variety of other fruits and vegetables. Yumbo men also resorted to wage labor to obtain cash for the few purchases deemed necessary. By the mid-1970s, increasing numbers of Quichua speakers settled around some of the towns and missions of the Oriente. Indians themselves had begun to make a distinction between Christian and jungle Indians. The former engaged in trade with townspeople. The Jívaros, in contrast to the Christian Quichua speakers, lived in more remote areas. Their mode of horticulture was similar to that of the non-Christian Yumbos, although they supplemented crop production with hunting and some livestock raising.[23]

Shamans (curanderos) played a pivotal role in social relations in both groups. As the main leaders and the focus of local conflicts, shamans were believed to both cure and kill through magical means. In the 1980s group conflicts between rival shamans still erupted into full-scale feuds with loss of life.[23]

The Oriente Indigenous population dropped precipitously during the initial period of intensive contact with outsiders. The destruction of their crops by Mestizos laying claim to indigenous lands, the rapid exposure to diseases to which Indians lacked immunity, and the extreme social disorganization all contributed to increased mortality and decreased birth rates. One study of the Shuar in the 1950s found that the group between ten and nineteen years of age was smaller than expected. This was the group that had been youngest and most vulnerable during the initial contact with national society. Normal population growth rates began to reestablish themselves after approximately the first decade of such contact.[23]

Culture

Ecuador's mainstream culture is defined by its Hispanic Mestizo majority, and like their ancestry, it is traditionally of Spanish heritage, influenced in different degrees by Amerindian traditions, and in some cases by African elements. The first and most substantial wave of modern immigration to Ecuador consisted of Spanish colonists, following the arrival of Europeans in 1499. A lower number of other Europeans and North Americans migrated to the country in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in smaller numbers, Poles, Lithuanians, English, Irish, and Croats during and after the Second World War.

Since African slavery was not the workforce of the Spanish colonies in the Andes Mountains of South America, given the subjugation of the indigenous people through evangelism and encomiendas, the minority population of African descent is mostly found in the coastal northern province of Esmeraldas. According to local fables, this is largely owing to the 17th century shipwreck of a slave-trading galleon off the northern coast of Ecuador.

Ecuador's indigenous communities are integrated into the mainstream culture to varying degrees,[24] but some may also practice their own indigenous cultures, particularly the more remote indigenous communities of the Amazon basin. Spanish is spoken as the first language by more than 90% of the population, and as a first or second language by more than 98%. Part of Ecuador's population can speak Amerindian languages, in some cases as a second language. Two percent of the population speak only Amerindian languages.

Language

Most Ecuadorians speak Spanish,[25] though many speak Amerindian languages such as Kichwa.[26] People that identify as Mestizo, in general, speak Spanish as their native language. Other Amerindian languages spoken in Ecuador include Awapit (spoken by the Awá), A'ingae (spoken by the Cofan), Shuar Chicham (spoken by the Shuar), Achuar-Shiwiar (spoken by the Achuar and the Shiwiar), Cha'palaachi (spoken by the Chachi), Tsa'fiki (spoken by the Tsáchila), Paicoca (spoken by the Siona and Secoya), and Wao Tededeo (spoken by the Waorani). Though most features of Ecuadorian Spanish are those universal to the Spanish-speaking world, there are several idiosyncrasies.

Religion

According to the Ecuadorian National Institute of Statistics and Census, 91.95% of the country's population have a religion, 7.94% are atheists and 0.11% are agnostics. Among those with a religion, 80.44% are Roman Catholic, 11.30% are Protestants, and 8.26% other (mainly Jewish, Buddhists and Latter-day Saints).[27][28]

In the rural parts of Ecuador, indigenous beliefs and Catholicism are sometimes syncretized. Most festivals and annual parades are based on religious celebrations, many incorporating a mixture of rites and icons.[29]

There is a small number of Eastern Orthodox Christians, indigenous religions, Muslims (see Islam in Ecuador), Buddhists and Baháʼís. There are about 185,000 members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church),[30] and over 80,000 Jehovah's Witnesses in the country.[31]

The "Jewish Community of Ecuador" (Comunidad Judía del Ecuador) has its seat in Quito and has approximately 300 members. Nevertheless, this number is declining because young people leave the country towards the United States of America or Israel.[32] The Community has a Jewish Center with a synagogue, a country club and a cemetery. It supports the "Albert Einstein School", where Jewish history, religion and Hebrew classes are offered. Since 2004, there has also been a Chabad house in Quito.[33]

There are very small communities in Cuenca and Ambato. The "Comunidad de Culto Israelita" reunites the Jews of Guayaquil. This community works independently from the "Jewish Community of Ecuador".[34] Jewish visitors to Ecuador can also take advantage of Jewish resources as they travel[35] and keep kosher there, even in the Amazon Rainforest.[36] The city has also synagogue of Messianic Judaism.[37]

Music

The music of Ecuador has a long history. Pasillo is a genre of Indigenous Latin music. In Ecuador it is the "national genre of music." Through the years, many cultures have influenced to establish new types of music. There are also different kinds of traditional music like albazo, pasacalle, fox incaico, tonada, capishca, Bomba highly established in afro-Ecuadorian society like Esmeraldas, and so on.[38][39]

Tecnocumbia and Rockola are clear examples of foreign cultures' influence. One of the most traditional forms of dancing in Ecuador is Sanjuanito. It is originally from the north of Ecuador (Otavalo-Imbabura). Sanjuanito is a danceable music used in the festivities of the Mestizo and Indigenous culture. According to the Ecuadorian musicologist Segundo Luis Moreno, Sanjuanito was danced by Indigenous people during San Juan Bautista's birthday. This important date was established by the Spaniards on 24 June, coincidentally the same date when Indigenous people celebrated their rituals of Inti Raymi.

Cuisine

.jpg.webp)

Ecuadorian cuisine is diverse, varying with the altitude and associated agricultural conditions. Most regions in Ecuador follow the traditional three course meal of soup, a second course which includes rice and a protein such as meat or fish, and then dessert and coffee to finish. Supper is usually lighter, and sometimes consists only of coffee or herbal tea with bread.

In the highland region, pork, chicken, beef, and cuy (guinea pig) are popular and are served with a variety of grains (especially rice and corn) or potatoes.

In the coastal region, seafood is very popular, with fish, shrimp and ceviche being key parts of the diet. Generally, ceviches are served with fried plantain (chifles y patacones), popcorn or tostado. Plantain- and peanut-based dishes are the basis of most coastal meals. Encocados (dishes that contain a coconut sauce) are also very popular. Churrasco is a staple food of the coastal region, especially Guayaquil. Arroz con menestra y carne asada (rice with beans and grilled beef) is one of the traditional dishes of Guayaquil, as is fried plantain which is often served with it. This region is a leading producer of bananas, cacao beans (to make chocolate), shrimp, tilapia, mangos and passion fruit, among other products.

In the Amazon region, a dietary staple is the yuca, elsewhere called cassava. Many fruits are available in this region, including bananas, tree grapes, and peach palms.

Literature

Early literature in colonial Ecuador, as in the rest of Spanish America, was influenced by the Spanish Golden Age. One of the earliest examples is Jacinto Collahuazo,[40] an indigenous chief of a northern village in today's Ibarra, born in the late 1600s. Despite the early repression and discrimination of the native people by the Spanish, Collahuazo learned to read and write in Castilian, but his work was written in Quechua. The use of the Quipu was banned by the Spanish,[41] and in order to preserve their work, many Inca poets had to resort to the use of the Latin alphabet to write in their native Quechua language. The history behind the Inca drama "Ollantay", the oldest literary piece in existence for any indigenous language in America,[42] shares some similarities with the work of Collahuazo. Collahuazo was imprisoned, and all of his work burned. The existence of his literary work came to light many centuries later, when a crew of masons was restoring the walls of a colonial church in Quito, and found a hidden manuscript. The salvaged fragment is a Spanish translation from Quechua of the "Elegy to the Dead of Atahualpa",[40] a poem written by Collahuazo, which describes the sadness and impotence of the Inca people of having lost their king Atahualpa.

Other early Ecuadorian writers include the Jesuits Juan Bautista Aguirre, born in Daule in 1725, and Father Juan de Velasco, born in Riobamba in 1727. De Velasco wrote about the nations and chiefdoms that had existed in the Kingdom of Quito (today Ecuador) before the arrival of the Spanish. His historical accounts are nationalistic, featuring a romantic perspective of precolonial history.

Famous authors from the late colonial and early republic period include: Eugenio Espejo a printer and main author of the first newspaper in Ecuadorian colonial times; Jose Joaquin de Olmedo (born in Guayaquil), famous for his ode to Simón Bolívar titled La Victoria de Junin; Juan Montalvo, a prominent essayist and novelist; Juan Leon Mera, famous for his work "Cumanda" or "Tragedy among Savages" and the Ecuadorian National Anthem; Luis A. Martínez with A la Costa, Dolores Veintimilla,[43] and others.

Contemporary Ecuadorian writers include the novelist Jorge Enrique Adoum; the poet Jorge Carrera Andrade; the essayist Benjamín Carrión; the poets Medardo Angel Silva, Jorge Carrera Andrade; the novelist Enrique Gil Gilbert; the novelist Jorge Icaza (author of the novel Huasipungo, translated to many languages); the short story author Pablo Palacio; the novelist Alicia Yanez Cossio; U.S. based Ecuadorian poet Emanuel Xavier.

Art

The best known art styles from Ecuador belonged to the Escuela Quiteña, which developed from the 16th to 18th centuries, examples of which are on display in various old churches in Quito. Ecuadorian painters include: Eduardo Kingman, Oswaldo Guayasamín and Camilo Egas from the Indiginist Movement; Manuel Rendon, Jaime Zapata, Enrique Tábara, Aníbal Villacís, Theo Constante, León Ricaurte and Estuardo Maldonado from the Informalist Movement; and Luis Burgos Flor with his abstract, Futuristic style. The indigenous people of Tigua, Ecuador are also world-renowned for their traditional paintings.

Sport

The most popular sport in Ecuador, as in most South American countries, is football (soccer). Its best known professional teams include Barcelona and Emelec from Guayaquil; LDU Quito, Deportivo Quito, and El Nacional from Quito; Olmedo from Riobamba; and Deportivo Cuenca from Cuenca. Currently the most successful football club in Ecuador is LDU Quito, and it is the only Ecuadorian club that have won the Copa Libertadores, the Copa Sudamericana and the Recopa Sudamericana; they were also runners-up in the 2008 FIFA Club World Cup. The matches of the Ecuador national team are the most-watched sporting events in the country. Ecuador qualified for the final rounds of the 2002, 2006, and 2014 FIFA World Cups. The 2002 FIFA World Cup qualifying campaign was considered a huge success for the country and its inhabitants. Ecuador finished in 2nd place on the qualifiers behind Argentina and above the team that would become World Champion, Brazil. In the 2006 FIFA World Cup, Ecuador finished ahead of Poland and Costa Rica to come in second to Germany in Group A in the 2006 World Cup. Futsal, often referred to as índor, is particularly popular for mass participation.

There is considerable interest in tennis in the middle and upper classes of Ecuadorian society, and several Ecuadorian professional players have attained international fame. Basketball has a high profile, while Ecuador's specialties include Ecuavolley, a three-person variation of volleyball. Bullfighting is practiced at a professional level in Quito, during the annual festivities that commemorate the Spanish founding of the city, and it also features in festivals in many smaller towns. Rugby union is found to some extent in Ecuador, with teams in Guayaquil, Quito and Cuenca.

Ecuador has won three medals in the Olympic Games. 20 km racewalker Jefferson Pérez took gold in the 1996 games, and silver 12 years later. Pérez also set a world best in the 2003 World Championships of 1:17:21 for the 20 km distance.[44] Cyclist Richard Carapaz, the winner of 2019 Giro d'Italia, won a gold medal at the road cycling race of the 2020 Summer Olympics.[45]

Migration trends

In recent decades, there has been a high rate of emigration due to the economic crisis that seriously affected the economy of the country in the 1990s, over 400,000 Ecuadorians left for Spain and Italy, and around 100,000 for the United Kingdom while several hundred thousand Ecuadorians live in the US, (500,000 by some estimates) mostly in the cities of the Northeastern corridor. Many other Ecuadorians have emigrated across Latin America, thousands have gone to Japan and Australia. One famous American of Ecuadorian descent is pop music vocalist Christina Aguilera.

In Ecuador there are about 100,000 Americans and over 30,000 European Union expatriates. They move to Ecuador for business opportunities and as cheaper place for retirement.

As a result of the political conflict in Colombia and of the criminal gangs that had appeared in the areas of power vacuum a constant flow of refugees and asylum seekers as well as economic migrants of Colombian origin had moved into Ecuadorian territory. Over the last decade at least 45,000 displaced people are now residents in Ecuador, the Ecuadorian government and international organizations are assisting them. According to the UNHCR 2009 report as many as 167,189 refugees and asylum seekers are temporary residents in Ecuador.[46]

Following the migratory trend to Europe many of the jobs that those that left held in the country had been taken over by Peruvian economic migrants. Those jobs are mostly in agriculture and unskilled labor. There are no official statistics but some press reports estimate their number into the tens of thousands.

There is a diverse community of Middle Eastern Ecuadorians, numbering in the tens of thousands, mostly from Lebanese, Syrian and Palestinian descent; prominent in commerce and industry, and concentrated in the coastal cities of Guayaquil, Quevedo and Machala. They are well assimilated into the local culture and are referred commonly as "turcos" since the early migrants of these communities arrived with passports issued by the Ottoman Empire in the beginning of the century.[47]

Ecuador is also home to communities of Spaniards, Italians, Germans, Portuguese, French, Britons and Greek-Ecuadorians. Ecuadorian Jews, who number around 450 are mostly of German or Italian descent. There are 225,000 English speakers and 112,000 German speakers in Ecuador of which the great majority reside in Quito, mainly all descendants of immigrants who arrived in the late 19th century and of retired emigrees that returned to their terroir. Most of the descendants of European immigrants strive for the preservation of their heritage. Therefore, some groups even have their own schools (e.g. German School Guayaquil and German School Quito), Liceé La Condamine (French Heritage), Alberto Einstein (Jewish Heritage) and The British School of Quito (Anglo-British), cultural and social organizations, churches and country clubs. Their contribution for the social, political and economical development of the country is immense, specially in relation to their percentage in the total population. Most of the families of European heritage belong to the Ecuadorian upper class and had married into the wealthiest families of the country.

There is also a small Asian-Ecuadorian (see Asian Latino) community estimated in a range from 2,500 to 25,000, mainly consists of those having any amount of Chinese Han descent, and possibly 10,000 being Japanese whose ancestors arrived as miners, farm hands and fishermen in the late 19th century. Guayaquil has an East Asian community, mostly Chinese including Taiwanese, and Japanese, as well as a Southeast Asian community, mostly Filipinos.

See also

References

- "Contador Poblacional". ecuadorencifras.gob.ec. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Población del país es joven y mestiza, dice censo del INEC. (Census results, in Spanish) eluniverso.com (2011-09-02)

- Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities (2013), p. 422. Edited by Carl Skutsch

- Zambrano, Ana Karina; Gaviria, Aníbal; Cobos-Navarrete, Santiago; Gruezo, Carmen; Rodríguez-Pollit, Cristina; Armendáriz-Castillo, Isaac; García-Cárdenas, Jennyfer M.; Guerrero, Santiago; López-Cortés, Andrés; Leone, Paola E.; Pérez-Villa, Andy; Guevara-Ramírez, Patricia; Yumiceba, Verónica; Fiallos, Gisella; Vela, Margarita; Paz-y-Miño, César (2019). "The three-hybrid genetic composition of an Ecuadorian population using AIMs-InDels compared with autosomes, mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome data". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 9247. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.9247Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45723-w. PMC 6592923. PMID 31239502. S2CID 195354041.

- "EVOLUCIÓN DE LAS VARIABLES INVESTIGADAS EN LOS CENSOS DE POBLACIÓN Y VIVIENDA DEL ECUADOR" (PDF). Ecuador en Cifras. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- INEC https://web.archive.org/web/20110201014932/http://www.inec.gob.ec/preliminares/somos.html

- Preliminary Results http://www4.elcomercio.com/Pais/crecimos__2,1_millones_en_10_anos_.aspx%5B%5D

- "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision". United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "United Nations Statistics Division - Demographic and Social Statistics". Unstats.un.org. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "UNSD — Demographic and Social Statistics". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Población y Demografía". INEC. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- See also: Emigration from Ecuador

- Montinaro, F.; Busby, G. B.; Pascali, V. L.; Myers, S.; Hellenthal, G.; Capelli, C. (24 March 2015). "Unravelling the hidden ancestry of American admixed populations". Nature Communications. 6. See Supplementary Data. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6596M. doi:10.1038/ncomms7596. PMC 4374169. PMID 25803618.

- Godinho, Neide Maria de Oliveira (2008). O impacto das migrações na constituição genética de populações latino-americanas (Thesis).

- "Central America and Caribbean :: PAPUA NEW GUINEA". CIA The World Factbook. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Ethnic Groups". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Ethnic Groups". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494. -

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Whites and Mestizos". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Whites and Mestizos". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494. - "The World Factbook". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "FRONTLINE/WORLD . Rough Cut . Ecuador: Dreamtown – PBS". PBS. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Sierra Indigenous". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Sierra Indigenous". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494. -

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Oriente Indigenous". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Patricia Kluck (1989). "Oriente Indigenous". In Hanratty, Dennis M. (ed.). Ecuador: A country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. LCCN 91009494. - "South-images.com". Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Photos Indigenous people of Ecuador

- "Central America and Caribbean :: PAPUA NEW GUINEA". CIA The World Factbook. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- "Constitución Política de la República del Ecuador". Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- "El 80% de ecuatorianos es católico". Archived from the original on 11 August 2013.

- "El 80% de los ecuatorianos afirma ser católico, según el INEC". El Universo. 15 August 2012.

- Crane, R.; Rizowy, C. (8 December 2010). Latin American Business Cultures. Springer. p. 136. ISBN 9780230299108.

- "Ecuador: Facts and Statistics", Church News, 2020. Retrieved on 27 March 2020.

- 2015 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses. Watch Tower Society. p. 180.

- "Tokyo Isea Clinic – At Tokyo Isea Clinic, we conduct courteous counseling and consultation first, prior to plastic surgery". Archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- "Beit Jabad del Ecuador". 19 July 2011. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Congreso Judío Latinoamericano" [Latin American Jewish Congress]. congresojudio.org.ar (in Spanish).

- Traveling Rabbi Guide to Ecuador. Travelingrabbi.com (16 August 2012). Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- Keeping Kosher in the Amazon Rainforest. Travelingrabbi.com (4 May 2011). Retrieved on 2012-08-21.

- "Kehilá Mishkán Yeshúa" (in Spanish). mishkanyeshua.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Da Pawn". Spotify. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "La Máquina Camaleón". Spotify. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Borja,Piedad. Boceto de Poesía Ecuatoriana,'Journal de la Academia de Literatura Hispanoamericana', 1972

- Robertson, W.S., History of the Latin-American Nations, 1952

- Karnis, Surviving Pre-Columbian Drama, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1952

- Veintimilla, Dolores. "Dolores Veintimilla de Galindo". cmsfq.edu.ec (in Spanish). Archived from the original (DOC) on 25 April 2012.

- "The pride of Ecuador". Synergos.org. 14 August 1996. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- "Richard Carapaz conquers men's road race after Geraint Thomas crashes out". The Guardian. 24 July 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- "Table 1. Refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced persons (IDPs), returnees (refugees and IDPs), stateless persons, and others of concern to UNHCR by country/territory of asylum, end-2009" (ZIP). UNHCR. 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- See also: Lebanese Ecuadorians