White Earth Indian Reservation

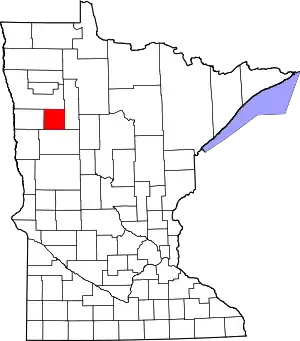

The White Earth Indian Reservation (Ojibwe: Gaa-waabaabiganikaag, lit. "Where there is an abundance of white clay") is the home to the White Earth Band, located in northwestern Minnesota. It is the largest Indian reservation in the state by land area. The reservation includes all of Mahnomen County, plus parts of Becker and Clearwater counties in the northwest part of the state along the Wild Rice and White Earth rivers. The reservation's land area is 1,093 sq mi (2,831 km²). The population was 9,726 as of the 2020 census, including off-reservation trust land.[1] The White Earth Indian Reservation is one of six bands that make up the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, their governing body for major administrative needs. It is about 225 miles (362 km) from Minneapolis–Saint Paul and roughly 65 miles (105 km) from Fargo–Moorhead.

The White Earth Reservation was created on March 19, 1867, during a treaty (16 Stat. 719) signing in Washington, D.C. Ten Ojibwe Indian chiefs met with President Andrew Johnson at the White House to negotiate the treaty. The chiefs Wabanquot (White Cloud), a Gull Lake Mississippi Chippewa, and Fine Day, of the Removable Mille Lacs Indians, were among the first to move with their followers to White Earth in 1868.

The reservation originally covered 1,300 square miles (3,400 km²). Much of the community's land was improperly sold or seized by outside interests, including the U.S. federal government, in the late 19th century and early 20th century. According to the Dawes Act of 1887, the communal land was to be allotted to individual households recorded in tribal rolls, for cultivation in subsistence farming. Under the act, the remainder was declared surplus and available for sale to non-Native Americans. The Nelson Act of 1889 was a corollary law that enabled the land to be divided and sold to non-Natives. In the latter half of the 20th century, the federal government arranged for the transfer of state and county land to the reservation in compensation for other property that had been lost.

In 1989, Winona LaDuke formed the White Earth Land Recovery Project, which has slowly been acquiring land privately held to add back to the value of the non-profit 501(c)(3) to be used for collateral. At that time, less than 10% of the land within the reservation boundaries was owned by tribal members.

The White Earth Band government operates the Shooting Star Casino, Hotel and Event center in Mahnomen, Minnesota. The entertainment and gambling complex employs over 1000[2] tribal and non-tribal staff, with a new location in Bagley, Minnesota.

History

Prior to the decision to create a reservation in Mahnomen County there were Chippewa/Ojibwa living there. G Company had a large component of bi-racial White Earth Chippewa.[3] Their military service was the result of Crow Wing Americans using alcohol to get the bi-racial Chippewa intoxicated to sign papers as substitutes to fight in the Civil War. Chief Hole in the Day was furious when he learned of the subterfuge.[4]: p.201 One of those men was killed and buried with military honors before Company G even left St Cloud where they had been signed in.[5] They were posted forward to Fort Abercrombie in Dakota Territory. They arrived there on 3 September to find the Fort under Sioux attack. They went into action and helped break the siege.[6]: p.53–58 The Company joined the garrison immediately and survived the Sioux siege that followed. G Company remained there until the 9th Minnesota was sent south and participated in the Battle of Brice's Crossroads.[3] There G Company gained recognition as the best Skirmishers.[3] They fought a difficult but successful rear guard action along with two African American Regiments, the 55th and 59th U.S. Colored Regiments.[7] They were credited with providing needed cover fire that kept 59th troops from being engulfed while dismantling a bridge's decking to thwart Confederate Cavalry from following.[8] Afterwards they participated in the Battle of Tupelo, Burning of Oxford, Mississippi, Battle of Nashville, Mobile Campaign (1865) and the Battle of Fort Blakeley and the Battle of Spanish Fort. They returned to St. Paul, Minnesota in August 1865 having taken few casualties.

Originally, the United States wanted to relocate all Anishinaabe people from Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota to the White Earth Reservation in the western part of Minnesota. It planned to open the land of the vacated reservations to sale and settlement by European Americans. The US government even proposed relocating the Dakota people to the White Earth Reservation, although the two peoples had been traditional enemies since the Anishinaabe had invaded their land in the late 18th century. The US continued to promote this policy until 1898.

Before the Nelson Act of 1889 took effect, groups of Anishinaabe and Dakota peoples began to relocate to the White Earth Reservation from other Minnesota Chippewa and Dakota reservations. The 1920 census details provide data on the origins of the Anishinabe people living on the White Earth Reservation, as they indicated their original bands. There were 4,856 from the Mississippi Band of Chippewa (well over 1,000 had come from Mille Lacs, and many were Dakota); the Pillagers numbered 1,218; the Pembina Band were 472; and 113 were from the Fond du Lac and Superior Chippewa bands.

On July 8, 1889, the United States broke treaty promises; it told the Minnesota Chippewa that Red Lake Reservation and White Earth Reservation would remain, but that the others would be eradicated. It also told them the Chippewa from the other Reservations would be relocated to White Earth Reservation. Instead of dealing with the Chippewa of Minnesota on a nation-to-nation level, the United States put decisions about communal land use to a vote of tribal members. It said that the decision to accept land allotments under the Dawes Act would be settled by a vote of individual adult Chippewa males, rather than allowing the tribe to make a decision according to their own traditions of council. Included in the decision to allow allotment was that lands classified as surplus, after all households received allotments, would be declared 'surplus' and could be sold to non-Chippewa, namely, the European Americans. Chippewa leaders were outraged. They knew they could count on the average Anishinaabe adult male to obey the council's decision. But, included in the voting were many Dakota men, who were not part of their tribe.

The Chippewa also mistrusted administration of the vote; the whites, who had an interest in allotment, counted the total number of votes, rather than the Chippewa. Red Lake leaders warned the United States about reprisals if their Reservation was violated. The White Earth and Mille Lacs reservations overwhelmingly voted to accept land allotments and allow surplus land sold to the whites. Supposedly the Leech Lake Reservation's men also overwhelmingly voted to accept land allotments and have the Reservation surplus land sold to the whites. The events of October 1898 indicate otherwise.

At the time (1889), the White Earth Reservation covered 1,093 sq. mi. After the votes were counted, the whites claimed that voting men had overwhelmingly voted to accept land allotments and have the Reservations surplus land sold to the whites. After this process, only a small portion of the White Earth Reservation remained. It was located in the northeast part of the White Earth Reservation and was only a fraction of the original size. All other Minnesota Chippewa reservations were closed and emptied of Native Americans. The rebellion which occurred on the Leech Lake Reservation in 1898 saved Minnesota's Chippewa reservations, including the White Earth Reservation and probably the Red Lake Reservation, and the Chippewa reservations of Wisconsin.

White Earth, like the Red Lake and Leech Lake reservations, is known for its tradition of singing hymns in the Ojibwe language.[9]

Communities

White Earth Reservation has many settlements located within its borders. Some are predominantly non-Indian, or include a large percentage of mixed-bloods. Today, how individuals live in terms of their culture often determines whether they are considered Ojibwe. Some community members prefer to identify as Anishinaabe or Ojibwe rather than "Chippewa" while others do not. Some claim the word "Chippewa" is the anglicized form of Ojibwe that came to be used by European settlers. According to tradition , the Ojibwe had a patrilineal society in which inheritance and descent was passed down paternal lines. Children were considered born into their father's clan and took their social status from his people.

At one time , children who had white fathers were not considered Ojibwe; such children had no formal place in the tribe unless they were adopted by a male of the tribe, as their biological father did not belong to a tribal clan. Over time, many unions were made among Ojibwe and Europeans, typically of European males and Ojibwe women. Their mixed-race descendants have taken a variety of roles: some bridging the cultures; others identifying with one or the other. The questions of ancestry and style of life continue to be contentious.

Predominantly, Indian settlements include Elbow Lake; Naytahwaush, the largest Indian community on the Reservation; Pine Point; Rice Lake; Twin Lakes; and White Earth, which is the second-largest Indian settlement on the Reservation. The following communities are considered to have predominantly Indian populations when their mixed-blood residents are included, whether or not those are enrolled tribal members: Waubun, Ogema, and Callaway. The largest community is Mahnomen, which is predominantly non-Indian in population.

Tiny settlements that are likely predominantly Native American include Mahkonce, which is very rural; Maple Grove Township; Pine Bend; Roy Lake, a popular tourist and vacation destination; and the region around Strawberry Lake, which is also popular with vacationers. In July 2007, according to the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, the total number of enrolled members of the White Earth Reservation is 19,291. Most members live off-Reservation, particularly those of Dakota ancestry. Some live in Minneapolis or other cities that offer more economic prospects.

Demographics

As of the census of 2020,[1] the combined population of the White Earth Reservation and associated off-reservation trust land was 9,726. The population density was 8.9 inhabitants per square mile (3.4/km2). There were 4,989 housing units at an average density of 4.5 per square mile (1.7/km2).

The White Earth Reservation has a large non-Native population, as the Nelson Act of 1889 and subsequent legislation permitted sales of tribal lands to white settlers.[10] In 2020, the racial makeup of the reservation and off-reservation trust land was 44.7% Native American, 43.2% White, 0.1% Asian, 0.1% Black or African American, 0.5% from other races, and 11.5% from two or more races. Ethnically, the population was 2.1% Hispanic or Latino of any race.[1]

The chairwoman of the White Earth Reservation says that the Indian populations of reservations are higher than counted during censuses. She said that many Reservation families had more than one family sharing the same residence, and these were not always counted. In some cases up to three families shared the same residence. During census counts, the extra families will likely not participate for fear of being evicted from their homes. It may be that the population of the White Earth Band is larger than that of whites on the reservation.

Economy

White Earth Reservation has an economy which is similar to other Native American reservations. In 2011, the government of the White Earth Reservation employed nearly 1,750 employees. The tribal payroll was near $21 million. The government of the White Earth Reservation employs non-Indians as well as Chippewa from off the reservation in order to fill its staffing needs. The Band issues its own reservation license plates to vehicles.

The White Earth Reservation owns and operates an Event Center, a hotel, the Shooting Star Casino, the White Earth Housing Authority, the Reservations College, and other business enterprises.

The poverty rate on the White Earth Reservation may be near 50%. The unemployment rate on the White Earth Reservation is near 25%.[11]

Topography

White Earth Reservation is situated in an area where the prairie meets the boreal forest. About half the Reservation is covered by a forest and lakes, with second-growth trees. In the late 19th century, lumber companies clear–cut much of the original forest that had covered the Reservation.

The western part of the Reservation is prime prairie land. Many farms are located in this section. Another area of numerous farms is the extreme northeastern section of the Reservation.

The most dense forest is situated between Callaway and Pine Point, on up to just west and north of Mahkonce. North of there, the forest becomes less dense, especially around the Pine Bend and Rice Lake regions. The region between Mahkonce and Pine Bend has a few farms.

Many lakes dot the Reservation's land. Large lakes include Bass Lake; Big Rat Lake; Lower Rice Lake; Many Point Lake; North Twin Lake-South Twin Lake; Roy Lake; Round Lake; Snider Lake; Strawberry Lake; Tulaby Lake; and White Earth Lake. The White Earth Land Recovery Project encourages ownership of reservation land by members of the White Earth Band, as well as projects for reforestation and revival of the wild rice industry on the reservation's lakes.[12] It sells a reservation brand of wild rice and other products.

The White Earth Reservation holds the 160,000-acre White Earth State Forest. The Reservation's land is still recovering from the effects of the destruction which the lumber companies caused over a century ago. The Reservation is especially beautiful during the spring, summer and autumn.

Climate

Climate conditions on the White Earth Reservation are extreme. Winters are long and cold. During the months of December, January, and February, average low temperatures are 1, -6, and 0 (Fahrenheit) at Mahnomen. Average high temperatures for the same winter months are 20, 14, and 21. The summer months of June, July, and August have high temperatures that average 76, 81, and 80 at Mahnomen. Average low temperatures during the same summer months are 52, 56, and 54 at Mahnomen. Precipitation is influenced by the forest and many lakes which are located within the Reservation's borders. Average yearly precipitation at Mahnomen is over 22 inches.

See also

References

- "2020 Decennial Census: White Earth Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, MN". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- "Shooting Star plans new casino in Bagley; hopes to open in the spring | Grand Forks Herald". Archived from the original on December 4, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- One Drop In A Sea Of Blue, John B. Lundstrom, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd, St Paul, MN, 2012, p.10

- Chief Hole-in-the-Day and the 1862 Chippewa Disturbance A Reappraisal, Mark Diedrich, Minnesota History Magazine, Spring 1987, p.200 Minnesota Historical Society, 345 Kellogg Blvd, St Paul, MN

- St Cloud Democrat[volume], October 09, 1862, Image 2, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Bldg, 10 First Street SE, Washington, DC

- Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Sioux Uprising of 1862 (2nd ed.). Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0873511032.

- Chippewa Indians, Natchez Trace Parkway, 10 October, Facebook, https://z-upload.facebook.com/NatchezTraceParkwayNPS/posts/5842469509099167

- MS Final Stands Interpretive Center, History Museum at Baldwyn, Mississippi, October 10, 2022, Facebook,

- "At White Earth, hymns a unique part of a renewed Ojibwe culture". Park Rapids Enterprise. January 14, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- Janke, Ronald A. (1982). "Chippewa Land Losses". Journal of Cultural Geography. 2 (2): 84–100. doi:10.1080/08873638209478619. ISSN 0887-3631. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- The White Earth Reservation is classified as the poorest reservation in the State of Minnesota.

- Gunderson, Dan (March 7, 2023). "Tribal opposition stops large dairy project near White Earth Reservation". MPR News. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

Sources

- White Earth Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Minnesota United States Census Bureau

- Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2011.

- Treuer, Anton. Ojibwe in Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

External links

- White Earth Reservation

- White Earth Land Recovery Project

- "White Earth" at Minnesota Indian Affairs Council

- 'Archival Images of White Earth Mission', Saint Benedict's Monastery Archives