White-crowned parrot

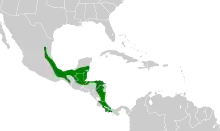

The white-crowned parrot (Pionus senilis), also known as the white-crowned pionus in aviculture, is a small parrot which is a resident breeding species ranging from eastern Mexico to western Panama.

| White-crowned parrot | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Macaw Mountain Bird Park, Honduras | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Pionus |

| Species: | P. senilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Pionus senilis (Spix, 1824) | |

| |

It is found in lowlands and foothills locally up to 1600 m altitude in forest canopy and edges, and adjacent semi-open woodland and second growth. The 3 to 6 white eggs are laid in an unlined nest, usually a natural cavity in a tree or a hollow palm stub.

The white-crowned parrot is 24 cm long and weighs 220 g. The adult male has a white forehead and crown, the feature which, likened to an old man's white hair, gave rise to the specific name senilis. The throat is white, and the rest of the head, neck and breast are dull dark blue. The belly is light green, and the upper parts are dark green, with a yellow-olive shoulder patch. In flight, the blue underwings and red vent are conspicuous features. The female white-crowned parrot is similar to the male, but the blue plumage fades into scaling on the lower breast and the shoulder patch is duller. Young birds have little blue on the head and neck or red on the undertail, and the crown feathers are green edged with white. The extent of the area of white on the head gives no indication of gender, as there can be considerable variance in individuals.

The white-crowned parrot feeds in social flocks of 30–50 birds, which may wander outside the breeding range once nesting has finished. It feeds on various seeds, nuts and fruits, and can be a pest in crops of corn or sorghum, and commercial fruit plantations. It can be unobtrusive when feeding since it is slow-moving, usually silent, and keeps in the canopy. However, at rest it often perches conspicuously at the top of an unopened palm frond.

Description

The white-crowned parrot is a medium-sized parrot of about 24cm in length. It has a broad body and a short tail, with a dark brown iris and brownish-pink eye ring. The bill is yellowish with a slight green coloration. Its forehead, crown and lores are pure white with white patch on chin and center of throat. The belly is mainly green; the basal colors of feathers on the breast are green with dark blue and purplish-blue tips, and light blue at the subterminal band. This scaly effect is also apparent in the feathers on cheeks and hindneck that are basally green with light bluish-green and purplish-blue at the subterminal band. The mantle and back are soft and shiny in a reddish brown color, with green scapulars that are reddish and yellowish-brown on tips and outer webs. They have violet blue primary coverts and green greater coverts; the lesser and median coverts are reddish-brown with paler tips which gives the wing a spotty appearance. The rump and upper tail coverts are brighter green with red undertail coverts. The upper wing is covered in brown patches and pale bluish-green in underwing.[2] The physical attributes in both sexes are similar. The juvenile has head, hindneck, and breast covered in green, with light yellowish cheeks and crown. The white-crowned parrot is widely sympatric across Mexico and western Panama.[2] Similar species include the brown-hooded parrot (Pyrillia haematotis); it has a brown head and white lores, but no white crown, nor red undertail coverts.[3] Its body is mainly green with visible red axillaries during flight, rapid wingbeats, and a high-pitched voice. Another species, the blue-headed parrot (Pionus menstruus) is mainly green with a bright blue head and neck, red undertail coverts, and yellowish wing coverts.[2] The white-crowned parrot has a fast wingbeat and climbs onto branches whilst feeding. They are often in pairs or small flocks except during breeding seasons. They are very cautious and will fly away while screeching loudly when approached. Their harsh voice will screech like kreeek-kreeek or kree-ah-kee-ah during flight, but can become unnoticeable and silent in the tree canopy.[3]

Distribution and habitats

The Pionus parrots include the white-crowned, white-capped, dusky, blue-headed, bronze-winged, Maximilian, red-billed, and plum-crowned Pionus.[4] They are native to Central and South America. The white-crowned Pionus is the rarest of these eight Pionus species. The white-crowned parrot inhabits the Caribbean slope in Central America from southeast Mexico to western Panama.[3] They are found in southeastern Mexico from southern Tamaulipas and eastern San Luis Potosí through Campeche and Quintana Roo to Costa Rica, and on both slopes (Chiriquí and western Bocas del Toro) in western Panama. Although this species is distributed over a broad area, its highest abundance is in Costa Rica. The population is still considered stable despite being hunted for food, crop pest, bird trade, and its habitat being deforested.[2] Their habitat is a humid tropical zone of forest and woodland with local growth of pine-oak trees and savanna. They are more commonly found in the lowlands and foothills of the Caribbean slope, but have also been reported from forest edge and cultivated areas with pastures, scattered trees, and wooded streams. The major food sources include ripening seeds, palm fruits, crops.

Behavior and ecology

The Pionus parrot is the earliest known captive bird;[5] they have become popular companion birds due to their ideal size and temperament. Most parrots, however, retain the behavior in the wild, and their ability to adapt as a pet bird varies considerably. A range of behavioral problems may arise as a consequence of poor adaptive ability, and bird keepers can assist their birds' living conditions through a deeper understanding of the species' behavior and habits.[6]

Housing

Pionus birds should be kept as individual pairs since they are very social animals; a pair of hens would be preferable over two males, as the males tend to be more aggressive.[4] Ideally, the aviaries should be made of stout wire mesh,[6] and be at least 1.5 times the wingspan of the parrot. Since parrots flap their wings to exercise, which maintains bone strength and functioning of joints to improve heart performance,[6] the enclosure should allow room for the parrot to spread their wings and accommodate airborne movement. The sleeping, reproductive, and molting cycles of birds are driven by the duration of light. Light that is gathered through the retina and harderian gland creates a visual image and transmits information about day length and light quality to the pituitary gland to pineal gland of the body which influence the cycles.[7] An adequate amount of light and dark period will facilitate sleep and maintain their physical and mental health. It is recommended that 12 hours of quiet and dark should be provided for sleep.[8] A cage cover can be employed to create a darkened environment for a favorable sleeping cycle.

Enrichment

In a captive environment, enrichment should be provided to encourage behavioral diversity and minimize abnormal behaviors. This can be achieved through different environmental enrichment, including social, occupational, physical, sensory, and nutritional enrichment.[9] This enrichment is particularly important during the developmental stage or juvenile time frame of birds.

Social

Social enrichment involves direct or indirect contact with humans such as visual or auditory interactions.[10] Since parrots communicate in a rich and subtle way, it is important to understand their common communication signals to maintain a healthy interaction between the parrot and humans.[10] Some common aggressive warnings seen from parrots are turning to opponent with head and neck extended, pecking at opponent without contact, wing flapping, bill gape, rapid sideways approach, and raised nape feathers and growling.[11] In contrast, affiliative behaviors include allopreening, allofeeding, spending time in proximity, reproductive behaviors, blinking mimicry, and unilateral stretching of wing and ipsilateral leg.[11] Other submissive behaviors include crouching, fluffed feathers, head wagging, foot lifting and avoidance.[11] Some behaviors can be similar, for instance, beak grinding or grating is exhibited when content which should not be confused with the short sharp sound of beak clicking that is expressed as a threat.[10] Observation of these communication behaviors help reinforce the human-parrot bond and shape undesired behaviors. The parrot should feel confident, playful, and adaptable rather than fearful of interactions.[12] By raising the height of the enclosure and making eye contact at side-long glances, it can increase the sense of security for a timid bird.[13] Positive reinforcement training is another source of social enrichment that builds upon the mutual relationship and bond.[14] For example, it can be used to teach the parrot to stay calm and comfortable when the owner approaches its cage, opens the door, reaches inside, feeds by hand, touches its wings, beak and feet, and other commands including step up, step down, and stay.[13] Consistent positive reinforcement throughout the parrot’s life will facilitate learning and develop the skills needed to live comfortably with humans.

Occupational

Occupational enrichment involves exercise and psychological related activities such as puzzles or ability to control the environment.[15] Psittacine birds have evolved to fly long distance, and daily exercise including flapping and flying, chewing, and shredding, and climbing and swinging is necessary for juvenile birds.[16] Appropriate daily exercises can help expend energy and reduce the occurrence of undesirable behavior such as screaming, pacing, and hyperactivity.[16] The activity of chewing is another source of occupational enrichment that should be encouraged as it helps stimulate the growth of masticatory muscles, fine and gross motor skills, and tactile exploration.[9] Less expensive materials or toys can be provided to prevent the bird from chewing on its perches, cage covers, or feathers.

Physical

Physical enrichment involves cage furniture, toys, and external home environment.[9] Cage furniture such as food and water dishes can influence the bird’s appetite, depending on the color, size, shape, and location of the dishes. Preferred foods may be placed in less desired locations such as the cage floor, while novel foods can be placed near favored perches to increase acceptance.[9] Another main component of cage furniture is the perch, which varies in sizes and materials. Perches that provide traction with a desirable degree of roughness for feet to keep claws from overgrowing, and allow beak cleaning and shaping, are ideal for juvenile birds.[16] Sand-based manzanita is a popular material: it is difficult to destroy while providing a pleasant texture for chewing. Perches should be of varying diameter to provide exercise for the feet and legs. Natural nontoxic branches and fruit trees that have not been sprayed with pesticides are a safe choice. Other materials such as twisted cotton wood are also popular. The types of toys vary in size, material, and suitability to provide independent play for juvenile birds; the toys may be grouped into categories of chewing, climbing, foot, and puzzles.[17] It also provides an alternative outlet for birds to deflect aggression. Although toys should be readily provided for optimal physical enrichment, it may be visually overwhelming and can limit space for exercise if the cage is crowded with toys.[13] The placement of the cage often affects the psychological comfort of the bird. A solid wall on at least one side of the cage to allow hiding is ideal for timid and sensitive juvenile birds.[17] Wooden or carboard boxes can be provided in the cage as hiding places for additional security.[16] In contrast, birds that are confident and highly social may prefer to be in the center of activity at home. Caution should be exercised in avoiding view of predators such as hawks or dogs when the cage is placed near windows.[17]

Sensory

Sensory enrichment involves aspects of visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory or taste which helps in the development of brain and prevent neophobia. Parrots can see into fluorescent and ultraviolet spectra which may influence their preferences with visual enrichment.[18] Many have distinct color preferences which is useful in selecting toys or introducing foods to their likes. For instance, the owner can avoid placing the cage near furniture or walls of color to which the bird may dislike or provoke phobic behavior.[9] Other forms of visual enrichment include mirror, television, videotapes, or digital recordings can be provided to birds that are home alone to reduce boredom. Auditory enrichment includes music and nature sound, and birds tend to enjoy higher pitched, and fast paced music.[9]

Nutritional

Nutritional enrichment involves the presentation, preparation, and delivery of foods, treats, and foraging opportunities.[15] A wide variety of food should be available during the parrot's juvenile stage, even if the base diet has fulfilled the nutritional requirements, in order to maximize the feeding options and enrichment for the adult stage. It is recommended to offer new food items at least three times per week.[14] Foraging enrichment for captive birds is encouraged to mimic the natural behavior in wild birds, which spend about four to six hours, or more than half of its waking hours, feeding.[19] For birds in captivity, foraging opportunities can be provided by hiding food in containers or toys, placing food in puzzle toys, or scattering food with inedible objects.[9] This may also help birds with nutritional neophobia by associating foraging containers with food.

Diseases

Pionus parrots are susceptible to neoplastic diseases including hemangiosarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, nephroblastoma, proventricular adenocarcinoma, lipoma, and xanthomas.[20]

Hemangiosarcoma

Hemangiosarcoma is a malignant tumor that commonly occurs at sites of beak, wings, feet, legs, and cloaca. It is locally invasive and multicentric. Surgical removal is not curative as the majority of tumors will regrow within days to months. An average age of affected birds is 11 years, with a range of 3 to 20 years, and there is no sex predilection.[21]

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant tumor that commonly occurs at sites of skin, and upper gastrointestinal tract. The site affects the survivability of the bird: infection in the beak, oral cavity, or esophagus often leads to death due to uncontrolled growth of tumor. Chronic irritation, feather picking, and inflammation will promote the proliferation of tumors. There is no sex predilection.[21]

Xanthomas

Xanthomas are masses or thickened and dimpled areas of skin that are yellowish-orange in appearance. They are invasive, and predominately occur in internal organs. The average age of occurrence is 10 years, with a range of 3 to 30 years. Treatment involves surgical resection or amputation, together with dietary modification, depending on the site of the xanthoma.[21]

The respiratory, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal systems of Pionus parrots are commonly infected by Aspergillus. Hand-fed pionus are more susceptible to candidiasis due to insanitary feeding equipment. Chlamydophila is also common in pionus birds in Central and South America.

References

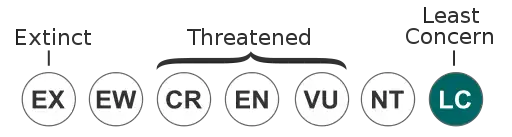

- BirdLife International (2016). "Pionus senilis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22686192A93101704. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22686192A93101704.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Juniper, T., & Parr, M. (1998). Parrots: A Guide to Parrots of the World (Boswell’s Correspondence;7;yale Ed.of) (3rd ed.). Yale University Press.

- Forshaw, J.M., & Knight, F. (2010). Parrots of the World. (Course Book ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Myers, S. H. (1998). Aviculture of Pionus Parrots Breeding, Care and Personality. Journal of American Federation of Aviculture, 25(3), 1–9. https://journals.tdl.org/watchbird/index.php/watchbird/article/view/1402

- Harcourt-Brown, N. H. (2009). Psittacine Birds. In Handbook of Avian Medicine (Second Edition) (2nd ed., pp. 138–168). Saunders Ltd. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-2874-8.00007-9

- Glendell G. (2017). BIRDS NEED TO FLY. The IAABC Journal. 2017;71(6)

- Kalmar, I. D., Janssens, G. P. J., & Moons, C. P. H. (2010). Guidelines and Ethical Considerations for Housing and Management of Psittacine Birds Used in Research. ILAR Journal, 51(4), 409–423. doi:10.1093/ilar.51.4.409

- Bergman L, Reinisch US. (2006). Comfort behavior and sleep. In: Luescher AU, editor. Manual of parrot behavior. Ames (IA): Blackwell Publishing., 59–62.

- Simone-Freilicher, E., & Rupley, A. E. (2015). Juvenile Psittacine Environmental Enrichment. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice, 18(2), 213–231. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2015.01.003

- Friedman SG, Edling TM, Cheney CD. (2006). Concepts in behavior: section I: the natural science of behavior. In: Harrison GJ, Lightfoot TL, editors. Clinical avian medicine, vol. 1. Palm Beach (FL): Spix Publishing., 46–59.

- Grindol D. (1998). Is your cockatiel being weird?. In: Grindol G, editor. The complete book of cockatiels. New York: Macmillan Publishing., 99–104.

- Hooimeijer J. (2003). Organizing a parrot walk/parrot picnic. Proceedings of the Annu Conf Assoc Avian Vet.

- Welle K. (1999) Psittacine behavior handbook. Bedford (TX): Association of Avian Veterinarians Publication.

- Shewokis R. (2008). Educating your clients on avian enrichment. Proceedings of the Annu Conf Assoc Avian Vet.

- Young RJ. (2003). Environmental enrichment for captive animals. Ames (IA): Blackwell Science, Inc;. p. 1–3.

- Wilson L. (2000). Considerations on companion parrot behavior and avian veterinarians. J Avian Med Surg; 14(4), 273–6.

- Wilson L, Linden PG, Lightfoot TL. (2006). Concepts in behavior: section II: early psittacine behavior and development. In: Luescher AU, editor. Manual of parrot behavior. Ames (IA): Blackwell Publishing.. 60–72.

- Graham J, Wright TF, Dooling RJ, et al. (2006). Sensory capacities of parrots. In: Luescher AU, editor. Manual of parrot behavior. Ames (IA): Blackwell Publishing., 33–41.

- Echols MS. (2004). The behavior of diet. Proceedings of the Annu Conf Assoc Avian Vet.

- Rich, G. A. (2003). Syndromes and conditions of parrotlets, pionus parrots, poicephalus, and mynah birds. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine, 12(3), 144–148. doi:10.1053/saep.2003.00021-5

- Reavill, D. R. (2004). Tumors of pet birds. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice, 7(3), 537–560. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2004.04.008

- Stiles and Skutch, A guide to the birds of Costa Rica ISBN 0-8014-9600-4