Westminster Trained Bands

The Westminster Trained Bands were a part-time military force established in 1572, recruited from residents of the City of Westminster. As part of the larger London Trained Bands, they were periodically embodied for home defence, such as during the 1588 Spanish Armada campaign. Although service was technically restricted to London, the Trained Bands formed a major portion of the Parliamentarian army in the early years of the First English Civil War. After the New Model Army was established in April 1645, they returned to their primary function of providing security for the palaces of Westminster and Whitehall. Following the 1660 Stuart Restoration, the City of London Militia Act 1662 brought them under the direct control of the Crown, with the Trained Bands becoming part of the British Army.

| Westminster Trained Bands | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1572–1662 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Role | Infantry |

| Size | 1–2 Regiments + 1 Troop of Horse |

| Part of | Middlesex Trained Bands |

| Garrison/HQ | Westminster |

| Engagements | Siege of Basing House Battle of Alton Battle of Cropredy Bridge Second Battle of Newbury |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Sir James Harington, 3rd Baronet |

Early history

The English militia was descended from the Anglo-Saxon Fyrd, the military force raised from the freemen of the shires under command of their Sheriff. It continued under the Norman kings, notably at the Battle of the Standard (1138). The force was reorganised under the Assizes of Arms of 1181 and 1252, and again by King Edward I's Statute of Winchester of 1285.[1][2][3][4][5]

The legal basis of the militia was updated by two Acts of 1557 covering musters and the maintenance of horses and armour. The county militia was now under the Lord Lieutenant, assisted by the Deputy Lieutenants and Justices of the Peace (JPs). The entry into force of these Acts in 1558 is seen as the starting date for the organised county militia in England.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

Trained Bands

Although the militia obligation was universal, it was clearly impractical to train and equip every able-bodied man, so after 1572 the practice was to select a proportion of men for the Trained Bands, who were mustered for regular training. The City of London and the Liberties of Westminster and the Tower Hamlets all fell within the boundaries of the County of Middlesex but had their own militia organisations: the difference was effectively between rural and suburban parishes of Middlesex.[12][13][14] The Armada Crisis in 1588 led to the mustering of the trained bands in April, when the Westminster contingent consisted of men from the following wards and parishes:

- City of Westminster

- St Giles-in-the-Fields

- St Martin-in-the-Fields

- High Holborn

- Gray's Inn Lane

- St Clement Danes

- The Savoy Parish with the Strand

William Fleetwood of Ealing in Middlesex[lower-alpha 1] was 'Colonel and Chief Captain' of the company, which consisted of 150 pikemen and 300 calivermen. The trained bands were put on one hour's notice in June and called out on 23 July as the Armada approached. They were quickly stood down once the danger had passed[10][15][16][17]

In the 16th Century little distinction was made between the militia and the troops levied by the counties for overseas expeditions, and between 1589 and 1601 Middlesex supplied over 1000 levies for service in Ireland, France or the Netherlands. However, the counties usually conscripted the unemployed and criminals rather than the Trained Bandsmen. Replacing the weapons issued to the levies from the militia armouries was a heavy cost on the counties.[18]

With the passing of the threat of invasion, the trained bands declined in the early 17th Century. Later, King Charles I attempted to reform them into a national force or 'Perfect Militia' answering to the king rather than local control.[19] In 1638 the Middlesex Trained Band consisted of 928 muskets and 653 'corslets' (pikemen with armour), together with the 80-strong Middlesex Trained Band Horse.[20] The trained bands were called upon in 1639 and 1640 to send contingents for the Bishops' Wars, though many of the men who actually went were untrained hired substitutes.[21] In 1640 Middlesex was ordered to hold a general muster on 24 May and then March 1200 men on 3 June to Harwich, there to be shipped to Newcastle upon Tyne on 8 June for service against the Scots.[20][22] Many of the officers of the LTBs had received their military training as members of the Honourable Artillery Company; Westminster had its own equivalent, the 'Military Company'.[16][23]

Civil War

Control of the trained bands was one of the major points of dispute between Charles I and Parliament that led to the English Civil War.[24][25] There is an often-repeated story that when Charles I returned from his Scottish campaign in October 1641 he ordered the guards on Parliament sitting at Westminster, which were provided by the city, Surrey and Middlesex TBs under command of the Puritan Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, to be replaced by the Westminster Trained Bands (many of whose tradesmen members were purveyors to the Royal Court at Whitehall Palace) under the command of the Royalist Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex, the Earl of Dorset. Subsequently, there were clashes between the new guards and the London apprentices.[26][27][28] However, this story has been refuted in the most detailed history of the LTBs, which points out that the guards were provided by the Westminster TBs 'and the four neighbour companies' of Middlesex TBs all along, and it was only the commanders who were changed. The clashes between TBs and apprentices may have been orchestrated by the anti-Royalist faction in Parliament. The LTBs, meanwhile, were maintaining order in the City itself. In January 1642, Parliament did replace the guard with the LTBs, but the King and Court having left London (with their patronage), the Westminsters protested their loyalty to Parliament. Their Royalist officers were purged, including Endymion Porter, captain of the St Martin in the Fields company. There was still suspicion of the Westminsters' commitment, they took their turns at guard duty and later on campaign in defence of Parliament, although their numbers were often few and defaulters numerous.[29][30]

At this point the Westminster Trained Bands were still under the authority of the deputy lieutenants and sheriffs of Middlesex, together with the unincorporated parishes of St Martin-in-the-Fields and St Giles in the Fields, parts of the parishes of St Sepulchre Without Newgate and St Andrew Holborn, the Liberty of the Rolls around Chancery Lane, and the Liberty of the Savoy in the parishes of St Clement Danes and St Mary Savoy.[30] Together these constituted the Westminster Liberty Regiment (also known as the Westminster Red Regiment from the colour of its flags) under the command of Sir James Harington, MP, whose own company was recruited from around Temple Bar. Other companies are known to have come from the Parish of St Margarets, which included the Palace of Westminster, and from around Holborn Bar.[23][30][31][32]

The Westminsters spent August 1642 searching houses for 'malignants', arresting a number of Roman Catholic priests.[30] When open was broke out between the King and Parliament, neither side made much use of the trained bands beyond securing the county armouries for their own full-time troops.[33] The main exception was the London area, where the large and well-trained regiments supported Parliament, beginning with the Battle of Turnham Green in November, where Charles was turned away from the city.[34][35]

Lines of Communication

London had long outgrown the old city walls. At the time of Turnham Green the citizens had erected breastworks across all the streets leading to open country and set up guard posts. During the winter of 1642–3 volunteer work gangs of citizens constructed a massive entrenchment and rampart round the city and its suburbs, enclosing the whole of Westminster and the Tower Hamlets. Known as the Lines of Communication, studded with some 23 forts and redoubts, these defences were about 11 miles (18 km) long, making it the most extensive series of city defences in 17th century Europe. The Lines were completed by May 1643 and the City and suburban TB companies took their turns in manning the forts and key points, with one duty company responsible for Westminster.[36][37][38][39][40]

To share the burden of guarding these extensive lines, the LTB regiments each raised a regiment of 'Auxiliaries', as did the suburbs of Westminster, Southwark and the Tower Hamlets. The Westminster Auxiliary Regiment was raised in April 1643. Its first colonel was Herriott Washbourne, a member of the Honourable Artillery Company living in the city; later Col James Prince, a Westminster man, took over and Washbourne commanded a Troop in the London Trained Band Horse. Under Col Prince the regiment was known as the Yellow Auxiliaries. One of its companies was probably recruited from St Giles's and Bloomsbury. It companies were always under strength.[30][41][42]

In August 1643 the London Militia Committee took control of all the TBs within the Lines of Communication, the Westminsters being transferred from the Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex to a subcommittee at the Savoy and taking over the companies recruited from the other Middlesex parishes within the lines, including St Giles-without-Cripplegate, Clerkenwell, Finsbury and Islington. After the London Militia Committee took over it controlled 18 regiments of Foot, about 20,000 men at full strength. Not all could be called away at once – the need to man the defences and continue the economic life of the City precluded that – but during the active campaigning season the regiments took turns to do tours of duty in the field, receiving pay for a month.[30][36] At this time the regiment retained the older system of 300-man companies, making it the strongest under the London Militia Committee with 2018 men in September 1643.[43]

One City Brigade took part on the Earl of Essex's relief of the Siege of Gloucester and the subsequent First Battle of Newbury on the march home. Meanwhile, a great muster of the LTBs had been held in Finsbury Fields on 24 September and regiments were chosen by lot for a second brigade to join Sir William Waller's South Eastern Association army. One of the regiments selected was the Westminster Liberty Regiment, which mustered with 80 officers, 854 pikemen and 1084 musketeers in 7 companies under Harington's command. In view of Essex's successful expedition the second brigade did not march out immediately, but once his City Brigade had returned home Essex's army was too weak to hold Reading. The second brigade was then ordered to join Essex and Waller at Windsor to recapture Reading. However, news of a second Royalist army advancing through Hampshire under Lord Hopton forced a change of plan, and Waller and Essex separated, the former to Farnham to face Hopton, the latter to capture Newport Pagnell, each force accompanied by a London brigade. The Westminster Liberty Regiment was assigned to the brigade with Waller, which was commanded by Harington with the rank of Major-General.[23][31][35][32][44][45][46][47][48][49]

Basing House and Alton

Harington's brigade rendezvoused at Windsor on 25 October where the City Green Auxiliaries and Westminster Liberty Regiment were quartered at Windsor and Datchet and were joined by the Tower Hamlets Auxiliaries. The brigade left on 30 October marching via Bagshot and on through the night to Farnham. On 3 November it moved to Alton, Hampshire, where it joined Waller's army. The projected move to Winchester was halted by snow and the force returned to the barns and farm buildings it had occupied the previous night. By now numbers of the trained bandsmen were deserting and returning home. On 6 November the army moved to attack Basing House, and a 'commanded' body of musketeers skirmished with the defenders until they had used their ammunition and were relieved. Skirmishing continued around the outbuildings next day, but deputations from the London regiments asked Waller to be allowed to withdraw because of the bad weather, while the paid substitutes had run out of money. Waller compromised by allowing them into Basingstoke for rest. He then advanced against Basing House again on 12 November, in two columns, the Londoners being directed against the earthworks facing Basing Park, which they attacked vigorously, employing ladders and Petards. The Westminster TB musketeers got their Volley fire drill mixed up, with numerous front rank men killed and wounded by the second and third ranks firing too soon. With the Royalist artillery concentrating fire on this disordered formation, the Westminster musketeers broke and fled, and the assault failed. The Green Auxiliaries later recovered the guns and petards abandoned by the Westminsters. Large numbers of the Westminsters deserted, but were fined or imprisoned when they reached home.[31][35][45][47][49][50][51][52][53]

Next day, Waller was greeted by cries of 'Home, Home!', from the London regiments. Although their officers voted to fight Hopton's approaching army, the trained bandsmen refused (there had been rumours that they were to march to relieve the Siege of Plymouth). Waller abandoned this first Siege of Basing House and retired to Farnham, where food and pay was received. Hopton followed, but after some skirmishing under the guns of Farnham Castle he sent a force to capture Arundel Castle and the rest of his army went into winter quarters. On 12 December Waller mustered his army in Farnham Park and persuaded the London Brigade to stay with him until Christmas. That night he marched out as if to renew the siege of Basing, but instead turned south to Alton, where a brigade of Hopton's army was quartered. The Royalists were taken by surprise as Waller's infantry assaulted the town, the London Brigade supported by the regular garrison of Farnham Castle attacking from the west. The Westminsters and the Farnham Greencoats attacked a breastwork, whose defenders retired when outflanked by the Green Auxiliaries, allowing the brigade to enter the town. The Royalists defended the churchyard wall, but some London musketeers broke in and pushed them back into St Lawrence's Church. The Tower Hamlets forced their way into the church and the Royalists surrendered after their colonel was killed. After the Battle of Alton Waller returned to Farnham and proposed to recapture Arundel Castle, but the London Brigade refused, and Waller allowed them to march home on 20 December. The three regiments held a service of thanksgiving in Christ Church, Newgate Street, on 2 January 1644.[35][45][47][49][51][52][54][55][56]

Oxford and Cropredy Bridge

The Parliamentary leaders had ordered a concentration of all their armies in South East England to move against Oxford, but a new London brigade had to be provided before Waller's army could take the field. The London Militia Committee sent Harington with a fresh brigade composed of the suburban regiments: the Tower Hamlets TBs, the Southwark Auxiliaries and the Westminster Yellow Auxiliaries. Essex's army was at Reading, which had been abandoned by the Royalists. The two armies rendezvoused at Abingdon-on-Thames, which had also been abandoned by the Royalists, who were calling in their garrisons to form a field army. From 30 May to 1 June the London Auxiliaries were engaged in skirmishes as Essex tried to seize crossings over the River Cherwell at Gosford and Enslow, but on 1 June Waller got across the Thames at Newbridge, and the Royalist guards on the Cherwell were withdrawn. With Oxford partially encircled, the King and the Royalist field army left the city and moved to Evesham, followed by Essex and Waller to Stow-on-the-Wold. At this point the two Parliamentarian armies separated. Essex's army, accompanied by the City Auxiliary brigade, marched west to relieve the besieged garrison of Lyme Regis, while Waller with Harington's Suburban brigade shadowed the King's force.[35][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

Waller bombarded Sudeley Castle and forced its surrender on 8 June. There followed three weeks' pursuit of the King round the West Midlands before reaching the area of Banbury on 27 June. Having drawn reinforcements from Oxford the King's army was now prepared to give battle to Waller. The two sides skirmished across the Cherwell on 28 June. Next day the two armies marched parallel to each other on the high ground on either side of the river until Waller saw a gap opening in the Royalist line. To exploit the opportunity he sent his horse across the Cherwell at a ford and the bridge at Cropredy, bringing on the Battle of Cropredy Bridge. The Royalist horse responded aggressively, charging downhill and driving the Parliamentarians back across the river. The Tower Hamlets TBs stoutly defended the west side of the bridge, preventing the Royalists from crossing to complete the destruction of Waller's army. There was only skirmishing next day, but hearing that a reserve brigade of the City Auxiliaries was on its way, the King took the opportunity to break contact with Waller's battered force.[41][59][63][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75]

By now Waller's original London brigade (Harington's suburban regiments) had taken up the chant of 'Home, Home!', and when the colonel and a senior captain of the Southwark White Auxiliaries died of sickness, that regiment marched home to bury them. The remainder of Harington's brigade was finally allowed home on 14 August.[68][76][77][78][79] Meanwhile, the King's army followed Essex into the West Country, trapping and capturing his army at Lostwithiel.[80][81][82][83]

Second Newbury Campaign

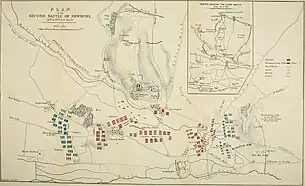

The Parliamentary leaders ordered a new concentration of forces to face the King's victorious army on its return from the west, with the Earl of Manchester's Eastern Association army joining the remnants of Essex's and Waller's at Newbury. London provided a fresh brigade of five regiments under Harington, including the Westminster Red Regiment,[23][31][84][85]

Difficulties in raising money led to the London brigade being late in mobilising, but Harington marched out with the Red Regiment of the LTBs and his own Westminster Red Regiment (over 1900 strong[43]) on 7 October, followed by the Blue Regiment of LTBs on 9 October; the remainder waited for their money. The brigade concentrated at Maidenhead on 17 October, though many of the men were still absent. On 19 October Harington was ordered to march with four regiments to rendezvous with the army at Basingstoke, leaving the Southwark regiment to garrison Reading. On 26 October the combined Parliamentary forces confronted the Royalist army at the Second Battle of Newbury. Essex and Waller worked round to attack from the west towards Speen village while Manchester's army remained to the east, using about 1000 skirmishers to distract attention from the pincer movement. The skirmishers were driven back, and in the afternoon Manchester attacked Shaw House when he heard cannon fire from the west. Despite Royalist reports that the London brigade was with Manchester, suffering heavy casualties in his skirmish line and final attack, they were in fact with Essex's army, which had made a 13 miles (21 km) march to get into position. Essex being sick, the army was deployed by Skippon, who reported that 'The two Red and [one] Yellow Regiments of the Citizens held the Enemy play on the right', while the Blue Regiment came up from reserve. Harington had his horse shot under him during the battle, and some of the cannon lost at Lostwithiel were recaptured. Nevertheless, the Parliamentarian combination misfired and the Royalists escaped the trap to reach Oxford.[86][87][88][89][90][91][92]

Reorganisation

The second Newbury campaign was the last active service of the war for the City and Suburban regiments. In 1645 Parliament finally organised its regional armies into a properly paid, equipped, and trained field army for service anywhere in the kingdom: the New Model Army. This powerful force no longer needed to be periodically reinforced by field brigades from London. In June 1645 the London Militia Committee raised a full-time regiment (the 'New Model of the Forts') to relieve the citizens from the burden of garrisoning the Lines of Communication round London. The TBs continued to man the 'Courts of Guard' (night patrol posts) around the city, and continued their musters and training[93][94]

The regiments were recruited back to strength for a general muster on 19 May 1646, when all 18 City and Suburban regiments were on parade in Hyde Park. But the First English Civil War had effectively ended with the surrender of King Charles to the Scots in April. All 18 regiments were paraded again for the funeral of the Earl of Essex in October, when the Westminster Yellow Auxiliaries lined the route of the procession. But the suburbs had begun agitating for their regiments to be released from the control of the London Militia Committee (which was controlled by the City authorities) and placed under their own committees approved by Parliament. [41][95][96]

By 1647 control of the English Trained Bands had become an issue between Parliament and the Army, as it had been between Parliament and the King. The Army regarded the TBs as its second line and tried to wrest control from the politicians, some of whom wanted to use them as a counterweight to the Army, which refused to disband until pay arrears were settled. However, when the army reached Hounslow the London and Suburban TBs refused to muster, the politicians caved in, and the New Model marched in. After the Army removed its opponents from Parliament ('Pride's Purge') the 'Rump Parliament' passed new Militia Acts that replaced lords lieutenant with county commissioners appointed by Parliament or the Council of State. An 'Ordinance to settle the Militia of Westminster and parts adjacent, within the County of Middlesex' was passed on 9 September 1647 (at this time the term 'Trained Band' began to disappear in most counties). The revived London Militia Committee demolished the Lines of Communication and returned the suburban TBs to local control.[95][97][98][99]

Under the Commonwealth and Protectorate the militia received pay when called out, and operated alongside the New Model Army to control the country.[100] During the Worcester campaign of the Third English Civil War in 1651, the Middlesex Militia were ordered to rendezvous at St Albans while the LTBs remained guarding London.[20][101]

Middlesex Militia

After the Restoration of the Monarchy, the English Militia was re-established by the Militia Act of 1661 under the control of the king's lords-lieutenant, the men to be selected by ballot. This was popularly seen as the 'Constitutional Force' to counterbalance a 'Standing Army' tainted by association with the New Model Army that had supported Cromwell's military dictatorship.[102][103][104][105]

The Middlesex Militia now included the Red Regiment of Westminster, the 'Blewe' (Blue) Regiment of Middlesex (within the environs of London) and the Westminster Troop of Horse, and these continued to at least 1728.[106][107][108] The Militia was reformed in the 1750s, when a new Royal Westminster Militia was raised, which eventually became the 5th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment).[109][110]

Uniforms and insignia

The flag of the Westminster Company in 1588 was described as 'Azure and Or panes cross Rouge in field argent chief', which is not heraldically correct but is interpreted to mean large squares in alternate blue and gold, with a cross of St George on a white band across the top.[17]

The Trained Bands were apparently not issued with uniforms, their regimental names being derived from the colours of their company flags or 'ensigns'. The Westminster Liberty Regiment, or Red Regiment, carried red ensigns with the seniority of the captains indicated by a number of silver stars.[23][31][32]

Similarly, the Westminster Auxiliaries were known as the 'Yellow Auxiliaries' from their ensigns by 1644; earlier (under Col Washbourne) the regiments may have carried blue ensigns. Seniority was marked by flames issuing from the corner of the Cross of St George in the canton: one for the Sergeant Major, two for the 1st Captain, etc.[42][41]

Footnotes

- Possibly William Fleetwood, Recorder of London.

Notes

- Fissell, pp. 178–80.

- Fortescue, Vol I, p. 12.

- Hay, pp. 60–1

- Holmes, pp. 90–1.

- Maitland, pp. 162, 276.

- Boynton, Chapter II.

- Cruickshank, p. 17.

- Fissell, pp. 184–5.

- Fortescue, Vol I, p. 125.

- Hay, pp. 384–7.

- Maitland, pp. 234–5, 278.

- Boynton, pp. 13–7.

- Cruickshank, pp. 24–5.

- Fissell, pp. 187–9.

- Hay, pp. 95–6.

- Roberts, p. 7.

- Leslie, ‘'Muster.

- Cruickshank, pp. 25–9, 126, 291.

- Fissell, pp. 174–8.

- Middlesex Trained Bands at BCW Project.

- Fissell, pp. 4, 10–6, 43–4, 246-63.

- Fissell, pp. 207–8.

- Roberts, pp. 49–52.

- Cruickshank, p. 326.

- Wedgwood, pp. 79, 100–1.

- Beckett, Wanton Troopers, pp. 38–9.

- Emberton, p. 58.

- Wedgwood, pp. 28–9.

- Nagel, pp. 26–35, 41.

- Nagel, pp. 102–9.

- Westminster Liberty Rgt at BCW Project,

- Dillon.

- Reid, pp. 1–2.

- Nagel, pp. 72–3.

- Roberts, pp. 20–7.

- Roberts, pp. 10–3.

- Emberton, pp. 64–70.

- Leslie, Defences.

- Nagel, pp. 71–2, 77.

- Sturdy.

- Westminster Auxiliary Rgt at BCW Project.

- Roberts, pp. 60–3.

- Roberts, pp. 17–18.

- Adair, pp. 22, 26–7.

- Kenyon, pp. 85–7.

- Nagel, pp. 131–6.

- Reid, pp. 164–6.

- Roberts, Appendix IV.

- Rogers, pp. 112–4.

- Adair, pp. 32–43.

- Burne & Young, pp. 120–2.

- Emberton, p. 83.

- Nagel, pp. 136–44.

- Adair, pp. 43–73.

- Nagel, pp. 144–52.

- Wedgwood, p. 263.

- Adair, pp. 144–6.

- Burne & Young, pp. 146–9.

- Emberton, p. 101.

- Kenyon, pp. 96–8.

- Nagel, pp. 179–90.

- Reid, pp. 169–70.

- Roberts, pp. 56–7.

- Rogers, pp. 125–31.

- Toynbee & Young, pp. 10–4, 25–50.

- Wedgwood, pp. 300–1, 304.

- Beckett, Wanton Troopers, pp. 103–4.

- Burne & Young, p. 152

- Kenyon, pp. 98–100.

- Nagel, pp. 190–1, 194–6.

- Reid, pp. 170–3.

- Rogers, pp. 132–4.

- Toynbee & Young, pp. 51–105.

- Wedgwood, pp. 306–9.

- Cropredy at UK battlefields.

- Beckett, Wanton Troopers, p. 107.

- Nagel, pp. 192–4, 197–203, 228–9.

- Toynbee & Young, pp. 105–8.

- Wedgwood, p. 331.

- Burne & Young, pp. 170–9.

- Kenyon, pp. 111–3.

- Reid, pp. 178–82.

- Rogers, pp. 155–62.

- Emberton, p. 112.

- Nagel, p. 208.

- Burne & Young, pp. 181–9

- Kenyon, pp. 118–9.

- Nagel, pp. 209–18

- Reid, pp. 184–91.

- Rogers, pp. 163–73.

- Wedgwood, pp. 356–8.

- Newbury II at UK Battlefields.

- Emberton, pp. 121–2.

- Nagel, pp. 208, 231–8.

- Nagel, pp. 238–45.

- Roberts, Appendix V.

- Beckett, 'Wanton Troopers, p. 150.

- Nagel, pp. 267–302.

- Reid, p. 221.

- Hay, pp. 99–104.

- 'Militia of the Worcester Campaign 1651' at BCW Project.

- Fortescue, Vol I, pp. 294–5.

- Hay, pp. 104–6.

- Kenyon, p. 240.

- Maitland, p. 326.

- Hay, p. 123.

- JHL & ACW.

- Linney-Drouet.

- Frederick, p. 284.

- Hay, pp. 256–7.

References

- John Adair, Cheriton 1644: The Campaign and the Battle, Kineton: Roundwood, 1973, ISBN 0-900093-19-6.

- Ian F.W. Beckett, Wanton Troopers: Buckinghamshire in the Civil Wars 1640–1660, Barnsley:Pen & Sword, 2015, ISBN 978-1-47385-603-5.

- Lindsay Boynton, The Elizabethan Militia 1558–1638, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1967.

- Lt-Col Alfred H. Burne & Lt-Col Peter Young, The Great Civil War: A Military History of the First Civil War 1642–1646, London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1959/Moreton-in-Marsh, Windrush Press, 1998, ISBN 1-900624-22-2.

- C.G. Cruickshank, Elizabeth's Army, 2nd Edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Mark Charles Fissel, The Bishops' Wars: Charles I's campaigns against Scotland 1638–1640, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-521-34520-0.

- Wilfred Emberton, Skippon’s Brave Boys: The Origin, Development and Civil War Service of London’s Trained Bands, Buckingham: Barracuda, 1984, ISBN 0-86023190-9.

- Sir John Fortescue, A History of the British Army, Vol I, 2nd Edn, London: Macmillan, 1910.

- J.B.M. Frederick, Lineage Book of British Land Forces 1660–1978, Vol I, Wakefield: Microform Academic, 1984, ISBN 1-85117-007-3.

- Col George Jackson Hay, An Epitomized History of the Militia (The Constitutional Force), London:United Service Gazette, 1905/Ray Westlake Military Books, 1987 ISBN 0-9508530-7-0.

- Richard Holmes, Soldiers: Army Lives and Loyalties from Redcoats to Dusty Warriors, London: HarperPress, 2011, ISBN 978-0-00-722570-5.

- John Kenyon, The Civil Wars of England, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988, ISBN 0-297-79351-9.

- Lt-Col J.H. Leslie, ‘A Survey, or Muster, of the Armed and Trayned Companies in London, 1588 and 1599’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 4, No 16 (April–June 1925), pp. 62–71.

- Lt-Col J.H. Leslie, 'The Defences of London in 1643', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 10, No 39a (April 1930), pp. 109–20.

- 'JHL' (Lt-Col J.H. Leslie?) & 'ACW', 'Tower Hamlets Militia', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol 5, No 19 (January–March 1926), pp. 44–7.

- C.A. Linney-Drouet (ed), 'British Military Dress from Contemporary Newspapers, 1682–1799: Extracts from the Notebook of the Late Revd Percy Sumner', Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol, 78, No 314 (Summer 2000), pp. 81–101.

- F. W. Maitland, The Constitutional History of England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1931.

- Lawson Chase Nagel, The Militia of London, 1641–1649, PhD thesis, Kings College London, 1982.

- Stuart Reid, All the King's Armies: A Military History of the English Civil War 1642–1651, Staplehurst: Spelmount, 1998, ISBN 1-86227-028-7.

- Keith Roberts, London And Liberty: Ensigns of the London Trained Bands, Eastwood, Nottinghamshire: Partizan Press, 1987, ISBN 0-946525-16-1.

- David Sturdy, 'The Civil War Defences of London', London Archaeologist, Vol 2, No 13 (Winter 1975), pp. 334–8.

- Margaret Toynbee & Brig Peter Young, Cropredy Bridge, 1644: The Campaign and the Battle, Kineton: Roundwood, 1970, ISBN 0-900093-17-X.

- Dame Veronica Wedgwood, The King's War 1641–1647: The Great Rebellion, London: Collins, 1958/Fontana, 1966.