Wembley Park

Wembley Park is a district of the London Borough of Brent, England. It is roughly centred on Bridge Road, a mile northeast of Wembley town centre[1] and 7.6 miles (12 km) northwest from Charing Cross.

| Wembley Park | |

|---|---|

View of Olympic Way in Wembley Park, 2019 | |

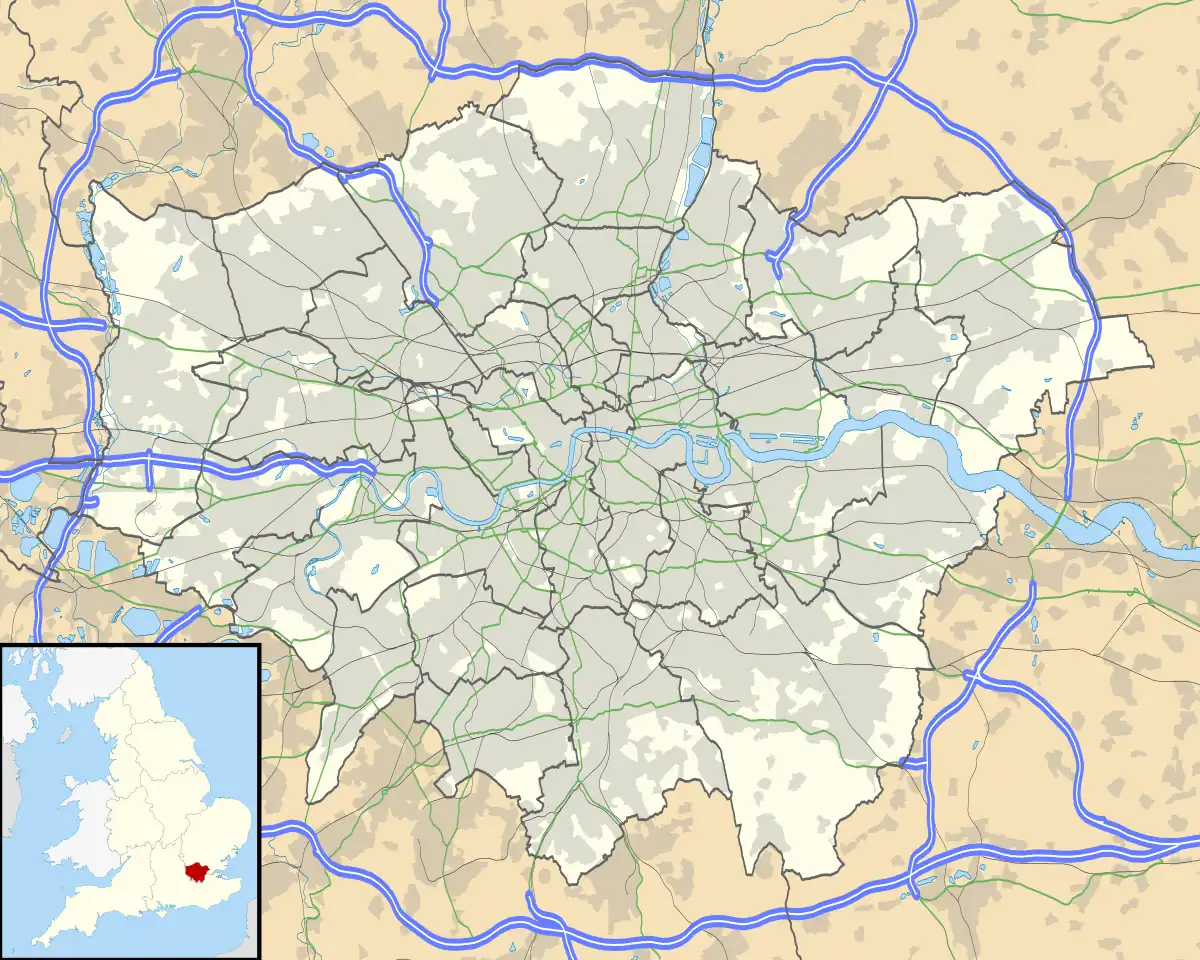

Wembley Park Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 30,877 (Tokyngton and Barnhill wards 2011) |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WEMBLEY |

| Postcode district | HA9 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

The name Wembley Park refers to the area that, at its broadest, falls within the limits of a late 18th-century landscaped estate in northern Wembley in the historic Middlesex county. Part of this estate became the location of development in the 1890s after being sold to Edward Watkin and the Metropolitan Railway cutting through the area. Wembley Park was developed into a pleasure and events destination for urban Londoners, with a large fairground made there. It was later also a key area of the Metro-land suburban development in the 1920s - the same decade Empire Stadium was built and the British Empire Exhibition was held.[2] Wembley Park continues to be a recreational centre today, being home to Wembley Stadium, England's primary football stadium and a major sports and entertainment venue; as well as Wembley Arena, a concert venue; among others.

Today the area continues new retail and housing development schemes near the stadium complex that have started since the early 2000s. The Chalkhill housing estate is also located in the area. The east is home to large industrial land, called Stadium Industrial Estate, adjacent to Brent Park; whereas to its north lies Fryent Country Park and to its north-east the Welsh Harp.

History

The Page family

Wembley was in the parish of Harrow, and the manor of Wembley was a sub-manor of Harrow. It belonged to the Priory of Kilburn. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Priory's lands in Wembley and Tokyngton came into the possession of Richard Page.

The Page family, successful local farmers, had already been leasing the land before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[3] The Pages became one of the largest and richest families in Middlesex.

Richard Page and Humphry Repton

Richard Page (died 1771) was the landowner and lord of the manor. He lived in Sudbury, west of Wembley. Around 1787, his son, also called Richard (1748–1803), had the ambition of converting 'Wellers' into a country seat, turning the fields around it into a landscaped estate.

In 1792 Richard Page decided to employ the famous landscape architect Humphry Repton (1752–1818) to convert the farmland into wooded parkland and to make improvements to the house. Repton was clearly impressed by Page's property. He wrote, "in the vicinity of the metropolis there are few places so free from interruption as the grounds at Wembly; and, indeed, in the course of my experience, I have seen no spot within so short a distance of London more perfectly secluded ... Wembly is as quiet and retired at seven miles distance as it could be at seventy."[4]

Later, writing to a friend in May 1793, Repton wrote of Wembley "on Wednesday I go to ... a most beautiful spot near Harrow. I wish I could shew it to you." Repton often called the areas he landscaped 'parks', and so Wembley Park owes its name as well as its origins to Humphry Repton.[5]

The area landscaped by Repton was larger than the current Wembley Park. It included the southern slopes of Barn Hill to the north, where Repton planted trees and started building a 'prospect house' – a gothic tower offering a view over the parkland. Repton may also have designed the thatched lodge that survives on Wembley Hill Road, to the west of Wembley Park. It is in a style frequently used by him, known as "cottage orne". Humphry Repton was in the habit of recording his designs in Red Books, but the one for Wembley Park, which would answer this speculation, has not survived.[6][7][8]

Richard Page lost interest in Wembley Park, partly because he had inherited a fully completed Capability Brown (1716–1783) landscape at Flambards in Harrow, so the house itself was never remodelled by Repton.[9] The tower on Barn Hill was never finished either. It became known as "Page's folly" (as with the later example of Watkin's Tower) and was eventually demolished.[10]

John Gray

The house appears to have been sold to John Gray (died 1828), a London brandy merchant, in 1802. The Page family retained the Barn Hill part of the park, some 91 acres (77 hectares).

Gray renovated and extended the house between 1811 and 1814, at a cost of £14,000. He may also be responsible for the late 18th- or early 19th-century cottage orné style lodge on Wembley Hill Road, if it was not built for Page by Repton. Whoever built it, it is thought to be the oldest property in Wembley.[7][11][12]

Even without the Barn Hill portion, the Wembley Park estate covered some 327 acres (132 hectares) from what is now Wembley Hill Road in the west to the River Brent in the east, and from the modern Chiltern Line in the south to Forty Lane in the north.

The current Empire Way (originally Raglan Gardens) now bisects Repton's landscape. Wembley Park Mansion, now with stucco facing as part of Gray's improvements, (and so known locally as 'The White House'), was situated west of Empire Way, while much of the parkland was to the east.

Wembley Park was described in 1834 as "beautifully diversified by fine grown timber judiciously placed, contributing a seclusion such as is scarcely elsewhere to be enjoyed, but at a considerable distance from the metropolis." Later visitors described "a grove, a pleasant retreat in summer – a scene of tranquility furnished with an old temple and a summerhouse" to the west of the house.

In 1880 the Metropolitan Railway extended its line from Willesden Green to Harrow, cutting through Wembley Park. The railway company bought 47 acres (19 hectares) of land from Gray's son, also called John. He died in 1887. Two years later Wembley Park was bought by the Metropolitan Railway Company for £32,500.[7][13] Its chairman was Sir Edward Watkin (1819–1901).

Watkin and Wembley Park

.jpg.webp)

Sir Edward Watkin, Chairman of the Metropolitan Railway Company, wanted Britain to have a bigger and better tower to rival the new Eiffel Tower in Paris. Watkin also hoped that this tower and an associated pleasure gardens would bring passengers to his Metropolitan Railway. Wembley Park, which was only 12 minutes by train from Baker Street, seemed the ideal location. The International (later Metropolitan) Tower Construction Company was formed to finance construction of the tower, with Watkin as chairman. It leased a significant part of Wembley Park from the Metropolitan Railway.[11][14]

The park became a sizeable pleasure garden that boasted cricket & football grounds, a large running track, tea pagodas, bandstands, a lake, a nine-hole golf course, a variety theatre and a trotting ring. Served by the new Wembley Park station, it officially opened in May 1894, though it had in fact been open on Saturdays since October 1893 to cater for football matches in the pleasure gardens.[15]

The tower design was chosen through a competition, judged in March 1890. The judges eventually awarded the 500 guinea prize to a design for a 1,200-foot steel tower by Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn. Originally intended to have eight legs, the plan was changed to a cheaper four-legged design and the height reduced to 1,150 foot. There were to be two stages, one 155 feet up and another at the halfway mark, with a viewing area at the summit. The platforms would be fitted with "restaurants, theatre, shops, Turkish baths, promenades and winter gardens."[16][17] The foundations were laid in 1892 and Watkin's Tower opened in 1896.

Over 100,000 people visited Wembley Park in the second quarter of 1894, though this declined to 120,000 for the whole of 1895 and only 100,000 for 1896. Despite an initial burst of popularity, the tower failed to draw large crowds. Of the 100,000 visitors to the Park in 1896 rather less than a fifth paid to go up the Tower.

In 1902 the Tower, now known as ‘Watkin's Folly’, was declared unsafe and closed to the public. In 1904 it was decided to demolish the structure, a process that ended with the foundations being destroyed by explosives in 1907, leaving four large holes in the ground.[15][18][19][20]

The loss of the tower did not diminish the park’s appeal as a public recreation ground, and it continued to offer football, cricket, cycling, rowing, athletics and in winter, ice skating on the frozen lake. After 1907 the Variety Hall in the park was used as a film studio by the Walturdaw Company Limited, founded by E.G. Turner. An 18-hole golf course was opened in 1912, and by the end of the First World War over 100 sports clubs were using the park.[15][21][22][23]

After 1889, the Metropolitan Railway built roads to the south-west of Wembley Park tube station, on that part of Wembley Park not allocated to the pleasure gardens or the Metropolitan track itself. In 1908, Wembley Park Mansion was demolished to allow construction of the new Manor Drive. The house had been a convent from 1905, housing French nuns fleeing the Third Republic's separation of Church and State.[5][15][24][25]

In 1906 the Great Central Railway opened a line and several stations between Neasden and Northolt Junction (today South Ruislip), where it connected with the newly built Great Western & Great Central Joint Line. The Great Central’s southernmost station on this short line (and so its southernmost station anywhere, other than its terminus at Marylebone) was Wembley Hill, just south of the Wembley Park pleasure gardens.[24]

The British Empire Exhibition

In 1921 the British Government decided to site the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park, on the site of Edward Watkin's pleasure gardens. The Urban District Council was opposed to the Exhibition, but its objections were overruled.[26] Wembley Stadium (then the Empire Stadium) was built for the Exhibition and, famously, the 1923 FA Cup Final was played there.[27][28][29][30][31]

Much of Humphry Repton's Wembley Park landscape was transformed in 1922–1923 during preparations for the Exhibition.[7]

In addition to the pavilions and kiosks there were a lake, a funfair, a garden and a working replica coal mine. There were also numerous restaurants, the most expensive of which was the Lucullus restaurant (in 1925 the Wembley Garden Club restaurant) near the exhibition gardens. In 1924 J. Lyons held a monopoly of catering, but the restaurant in the Indian Pavilion used Indian cooks and was advised by Edward Palmer "of Messrs. Veeraswami [sic] & Co." to serve as "Indian Adviser at the restaurant". In 1925 Veeraswamy & Co. ran the Indian restaurant, even though, for reasons both economic and political, the Indian Government did not take part in the 1925 season. Veeraswamy & Co. later founded the first Indian restaurant aimed at a non-Anglo-Indian white clientele in England, in Regent Street. It still survives, and was awarded a Michelin star in 2016.[32][33][34][35][36]

The British Empire Exhibition ran from 1924 to 1925, and while it failed to make a profit or reinforce conclusively the national attachment to the ideal of the British Empire, it did make Wembley a household name. Arthur Elvin's rescue of the Empire Stadium building then ensured that this continued, and that Wembley Park would remain the pre-eminent visitor attraction in west London, even though much of the Exhibition site was taken over by light engineering.[24]

Inter-war suburban development and ‘Metroland’

A few large houses had been built on parts of Wembley Park, south-west of Wembley Park tube station, as early as the 1890s. In 1906, when Watkin’s Tower closed, the Tower Company had become the Wembley Park Estate Company (later Wembley Ltd.), with the aim of developing Wembley as a residential suburb.[5][21]

Unlike other railways, from an early date the Metropolitan Railway had bought land alongside its line and then developed housing on it. In the 1880s and 1890s it had developed the Willesden Park Estate near Willesden Green station, and in the early 1900s it developed land in Pinner, as well as planning the development of Wembley Park.[37]

In 1915 the Metropolitan Railway’s publicity department created the term ‘Metro-land’ and gave the name to the company's annual guide.[38][39][40][41]

The 1924 Metro-land guide describes Wembley Park as "rapidly developed of recent years as a residential district", pointing out that there are several golf courses within a few minutes journey of it.[42]

One of the earliest Metroland developments was a 123-acre one at Chalkhill, within the curtilage of Humphry Repton’s Wembley Park. Metropolitan Railway Country Estates acquired the land shortly after it was created and began selling plots in 1921. The railway even put in a siding to bring building materials to the estate.[43]

The British Empire Exhibition further encouraged suburban development and could be said to have put Wembley on the map once again as a desirable location. Wembley’s sewerage was improved, many roads in the area were straightened and widened and new bus services began operating. Visitors were introduced to Wembley and some later moved to the area when houses had been built to accommodate them. Between 1921 and 1928 season ticket sales at Wembley Park and neighbouring Metropolitan stations rose by over 700%. Like much of the rest of West London, most of Wembley Park and its environs was built over, largely with relatively low-density suburban housing, by 1939.[24][44]

This population was served by a new 1,500 seater cinema, the Elite, later (from 1930) Capitol, which opened on 21 March 1928. The cinema was situated in the British Empire Exhibition's former conference hall on Raglan Gardens (today Empire Way).[45][46]

Film and television studios

In 1926 British Talking Pictures opened The Wembley Park Studios in what had been the British Empire Exhibition’s fine dining restaurant. When rebuilt in the late 1920s, Wembley Studios would become Britain's first purpose-built sound stages, though it was seriously damaged in a fire in October 1929, not long after it had opened. Perhaps due to the fire, the studio was never as successful as envisaged. It was taken over by Twentieth Century Fox to make 'quota-quickies', and then went into decline during and after the Second World War.[47][48]

In 1955 Wembley Film Studio was taken over by Associated-Rediffusion, ITV’s weekday broadcasters for London. Rediffusion added a new £1,000,000 television studio, which at the time was the largest in Europe. The Beatles performed there several times, notably on 28 April 1964.[49][50]

In 1968 Rediffusion lost its franchise. London Weekend Television continued to use the studio, but it went into decline until it was taken over by Fountain Studios in 1993.[51]

In 2016 Avesco, Fountain Studio’s owner, took the decision to sell the studios to Quintain after reporting financial losses in the previous year.[52]

In May 2018, it was announced that the studios would open in the latter half of 2018 as a flexible 1,000–2,000 seat theatre by Troubador Theatres (the same company that owns Wembley Park Theatre Ltd) as well as bar and restaurant.[53] This theatre opened as Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre in Summer 2019.[54]

The Empire Pool

In 1932 Arthur Elvin, who had saved the stadium in the 1920s, developed an interest in hosting Ice hockey. He decided to build an indoor Olympic-sized swimming pool that could be converted into an ice rink. It would also provide the venue for the swimming events at the 2nd Empire Games, which were held in 1934.

The building, called the Empire Pool, was designed by the engineer Owen Williams. Williams built a unique concrete structure, which opened on 25 July 1934.[55][56][57] It is now called The SSE Arena.

The building served as a public swimming pool until the start of the Second World War. It was last used for swimming when it hosted the aquatic events at the 1948 Olympics.[55] Numerous sporting and entertainment events have been held there over the years, ranging from basketball to pantomimes on ice. From 1959, and especially from the late 1960s onwards, The SSE Arena has become increasingly associated with popular music, hosting every major artist from the Beatles to the Stones, Bowie to Madonna.[58]

Wembley Town Hall

%252C_Wembley_-_geograph.org.uk_-_865102.jpg.webp)

Between 1937 and 1940 Wembley Borough Council built their new town hall in Kingsbury within the boundaries of Repton's original Wembley Park. It was designed by Clifford Strange and is described by Pevsner as "the best of the modern town halls around London, neither fanciful nor drab."[59]

In 1964 the new London Borough of Brent took over the town hall. It remained the headquarters of Brent until the new Brent Civic Centre, also in Wembley Park, opened in 2013.

The Wembley Town Hall building re-opened as the Lycée International de Londres Winston Churchill, in September 2015. The refurbishment preserves many elements of the original design.[60][61]

The Second World War

During the Second World War the Government initially banned large public events, but later realised that this had a demoralising effect. Sporting events, including football matches, returned to Wembley, although for a while after Dunkirk the Stadium became an Emergency Dispersal Centre, and later housed refugees from occupied countries. The Empire Pool was used as a permanent hostel for evacuated Gibraltarians, with its extensive windows blacked out.[24][62]

Arthur Elvin offered free admission to servicemen and servicewomen, and helped war charities.[63][64] Unofficial cup finals were held in the Stadium, as well as internationals against the home nations, and greyhound racing returned, albeit only in daylight hours, while Canadian troops invigorated ice hockey.

The Stadium was too large to conceal, and German aircraft used it to identify their location. They also dropped bombs on Wembley Park. At least two fell on the former British Empire Exhibition site, one fell very near Wembley Park station, and several fell on the suburban housing to the west of Empire Way. Light industry in Wembley Park helped the war effort, but the low concentration of bombs here compared to Tokyngton just south of it, suggests that it was not seriously targeted by the Luftwaffe.[65] In 1944, a V1 flying bomb fell onto the greyhound kennels. Two dogs were casualties and about 60 escaped onto the streets of Wembley.[66] An unexploded 50 kg bomb was uncovered during redevelopment work in May 2015.[67]

On 13 May 1945 the end of the War in Europe was marked by a Thanksgiving Service in Wembley Stadium, followed by a Victory Review and Commemoration Service in the same venue on 17 June. On 26 May 1945, England played their first Wembley International against a non-British side, drawing 2-2 with France in front of 65,000 spectators.[68][69]

By the end of the war more than one million service personnel had visited Wembley, as well as many civilians.[70]

The 1948 Olympics

.jpg.webp)

In March 1946, still recovering from the war, Britain put itself forward to host the Olympic Games for the second time in its history, seeing an opportunity to stage-manage an unparalleled global event and to demonstrate to the world that the worst effects of the war were in the past.[71][72][73]

There was limited preparation time. It was debated whether a sports festival was really necessary at such a time, but it was generally agreed that it could only bring an element of light relief and a wider image of progress, to which other nations could easily relate.[72]

Arthur Elvin supplied the Wembley site free of charge. Apart from the Stadium and Empire Pool, some of the old British Empire Exhibition buildings were used, notably the Palace of Engineering, so that no new venues were needed. Olympic Way was built at a cost of £120,000, using German POW labour.[74][75][76]

Wembley's sports facilities had survived the war in good condition and were considered adequate for Olympic competition.[77] Wembley Stadium hosted the opening ceremonies, the track-and-field competition, and other events. A cinder track, made with residue from the domestic fires of Leicester, was laid inside the stadium.[78]

Food rationing was still in force, but other competing nations, such as The Netherlands, contributed provisions. Athletes were provided with increased rations of 5,500 calories a day, on a par with the ration of a docker or a miner. The Games were on the least lavish scale ever seen, costing just £730,000 to put together. They became known as the Austerity Games. Many British athletes commuted to the Games on public transport. Even the "gold" medals were made from oxidised silver.[79]

However, each national team was assigned a vehicle with a uniformed female driver.[80]

The games opened at 4.00 p.m. (the time shown on Big Ben on the promotional literature) on 29 July 1948. There were 80,000 spectators on the first day.[81]

Though the 1936 Berlin Olympics had been televised, the Wembley games were the first Olympics to be broadcast by BBC television. Few people owned a television set, but nonetheless, the new medium helped to promote the Games in a way never seen before by the British public.[79]

The Empire Pool had never been a great success as a swimming venue, but it was ideal for the Olympics. For the first time at the Olympics, swimming events were held under cover. As the Empire Pool was longer than the standard Olympic length of 50 metres, a platform was constructed across the pool which both shortened it and could house officials.[82]

The Empire Pool also hosted the boxing and the diving, as it had at the Empire Games in 1934.[79]

In the stadium, some poor weather, and the inferior quality of the running track, slowed the track-and-field competition times. The fewest Olympic records were set in the history of the Games thus far, although the restricted women's competition was expanded to 10 possible events with the addition of the 200-metre run, the long jump, and the shot put.

British Guiana (now Guyana), Burma (now Myanmar), Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Korea, Lebanon, Pakistan, Puerto Rico, Singapore, Syria, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela were all nations sending teams for the first time. The 1948 Games were the first international competition that the Philippines, India and Pakistan officially entered as independent nations. As a team, India won their first medal as an independent nation in the field hockey competition. They were awarded the gold (also their first ever Olympic victory) when they beat Britain 4-0 in the final.[83]

Germany and Japan were not invited to the Games due to their roles as the aggressors in World War II. The Soviet Union was invited, but they declined. The Games were, however, attended by other Communist bloc countries, including Hungary, Yugoslavia and Poland.

A total of 4,104 athletes took part, from a record number of 59 nations (90% of all competitors were male). This compares with 10,000 athletes from 204 nations at the 2012 London games.[72][79]

A number of events made their Olympic debut at Wembley in 1948, including the women's 200 metres, long jump and shot put.[84]

The most successful individual athlete at these Games was Fanny Blankers-Koen of the Netherlands, known as "The Flying Housewife". A 30-year-old mother of three, whom many believed was too old to compete, she was pregnant at the time she won four gold medals: in the 100 metres, 200 metres, 80 metres high hurdles, and 4 x 100 metre relay. She was also a world record holder in the long jump and high jump and might have won further medals in these sports, but female athletes were limited to three individual events.[79]

Well over a million people attended across all the Olympic events at Wembley Park.[74]

Britain finished with a total of 20 medals, three of them gold, coming 12th in the medal table. The USA walked away with the top spot, as their medal tally reached 84, including 34 golds.[79]

The Stadium and Empire Pool after the Second World War

Speedway returned to the Stadium in 1946. The late 1940s was the sport’s heyday. The Wembley Lions supporters Club had 61,000 members in 1948, and one meeting attracted a crowd of 85,000, with a further 20,000 listening to the results on the radio outside. Speedway ended at Wembley in 1957, unless one counts a brief revival in 1970–71.[85]

The post-war years also saw religious events at the Stadium (a Roman Catholic celebration in 1950, a gathering of Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1951 and Billy Graham’s Greater London Crusade in 1954), as well as women’s hockey.[86] American football was first played in 1952, but would not really become a Wembley staple until the 1980s.[87]

Wembley remained primarily famous for football. The 1953 FA Cup Final became known as ‘the Matthew’s final’, because 38-year old Blackpool outside-right Stanley Matthews finally got the FA Cup Winners medal his skills so clearly deserved, though the hat-trick of goals that brought Blackpool victory was scored by Stan Mortensen.

Floodlights were installed in the Stadium in 1955.[29]

Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s the Empire Pool continued to be dominated by Ice hockey, skating, boxing and tennis. New events were introduced after the war, however, including a meeting of the Women’s League of Health and Beauty (1946), darts (1948), the All American Roller Skating Show (also known as Skating Vanities of 1949), pantomimes on ice (the first being Dick Whittington on Ice, in 1951) and swimming spectacles devised by Hollywood stars Buster Crabbe and Esther Williams. These last had to use temporary structures to retain water, as the swimming pool itself was no longer usable.[88]

International basketball had been played in the Pool before the war, but it now became a regular feature, starring the Harlem Globetrotters, who would perform at Wembley from 1950 until 1982.[88][89]

Most importantly, two popular music concerts intended to raise money for Vera Lynn’s SOS charity were held in 1959. These were the Record Star Show in March, and the Starlight Dance on 17 October. 9,000 people attended the Record Star Show, and the Starlight Dance was equally successful. The discovery that popular music events attracted large, new audiences would radically change the Empire Pool’s offer in the decades to come.[90]

More new events came to the Stadium and the Empire Pool in the 1960s, including ski-jumping in the Stadium, with a specially constructed tower and machine-produced snow.[86]

In 1963 the Stadium was given a new roof, ostensibly protecting all spectators.[29] On 18 June in the same year, Henry Cooper fought Cassius Clay (Mohammed Ali) in the Stadium, a change from holding boxing matches in the Pool.[91]

The 1966 World Cup

The 1966 World Cup kicked off at Wembley on Monday, 11 July 1966, with a match between England and Uruguay. It was a dull 0 - 0 draw.[92]

The other two teams who played at Wembley in the group stage were Mexico and France. In 1966, however, the World Cup competition was clearly not seen as being as important is it is now. Wembley Stadium refused to cancel a greyhound meeting on 15 July that clashed with Uruguay v. France, meaning that the match had to be played at White City.[93]

Having opened with a mediocre performance, Alf Ramsey's England went on to beat both Mexico and France in the group stage. They then beat Argentina 1-0 in the quarter finals and Portugal 2-1 in the semi-finals, both matches being played at Wembley.[94]

The final was played at Wembley on Wednesday 30 July 1966. England wore red because they had lost the toss of a coin to determine which team would have to wear their away colours. Haller scored for Germany in the 13th minute, with Hurst equalising in the 19th. Peters scored for England in the 78th minute, but Weber made it level just before the end of normal time.

What happened in extra time is the stuff of legends. Geoff Hurst scored a controversial, and in retrospect, wrongly allowed, goal in the 101st minute, and then a further goal in the 120th (119' 51"), just as the match was ending. "Some people are on the pitch… they think it's all over", said BBC commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme, adding "it is now" as Hurst's ball hit the back of the net.[94][95][96]

Less than two years later there was another famous English footballing victory at Wembley. On 29 May 1968 Wembley hosted the first of seven European Cup finals that have been played there so far (five in the old Stadium and two in the new one). Manchester United defeated SL Benfica 4–1 in front of a crowd of 92,225 people.[97]

The growth of popular music at Wembley

Inspired by the success of the 1959 popular music shows, the NME moved the Pollwinners Concert to the Empire Pool in February 1960. These concerts would continue there until 1973. The Pop Hit Parade Concerts, the ATV Glad Rag Ball, the Ready Steady Go Mod Ball (1964) and more Record Star shows all followed, some of them televised. Since all the major stars of the era, ranging from Billy Fury to Status Quo, played at these events, the Pool quickly became associated with popular music.[98]

The Beatles made their last official live appearance in Britain at the NME Annual Poll-Winners' All-Star Concert at the Pool on 1 May 1966. Although the concert was televised, the cameras were switched off while the Beatles played because Brian Epstein and ABC TV had failed to agree over terms. They were filmed receiving their awards, however.[99]

From 30 June to 2 July 1967 The Monkees played the Empire Pool. They were the first group to headline on their own. Many others would follow.[100]

On 13 July 1969 the band Yes performed at Wembley Stadium, on a bill that also included Alan Price, Don Partridge (aka "the King of the Buskers") and Status Quo, who would be the first act to open Live Aid, on exactly the same date 16 years later. This was the first popular music concert in the Stadium[101][102]

On 5 August 1972 a pop concert called The London Rock and Roll Show was held in the Stadium.[103][104] It was the first of several popular music concerts held in the Stadium in the ‘70s. Crosby Stills Nash & Young followed on 14 September 1974, and The Who, along with AC/DC and The Stranglers, on 18 August 1979.[105][106]

At the same time, the Empire Pool really took off as a concert venue. Promoters realised that it had a significantly larger capacity than even the Albert Hall. On 21 November 1971 Led Zeppelin’s Electric Magic Show became the first spectacular, theatrical rock concert at the Empire Pool.[107]

In the 1980s Wembley Arena became increasingly known for the use of lasers at concerts. Pink Floyd and Genesis were the best exponents of this style.[108]

Wembley Complex

In the 1970s Wembley Park became known as Wembley Complex, a group of venues serving different needs. The Complex included Wembley Stadium and the Empire Pool (renamed Wembley Arena on 1 February 1978), as well as new buildings, including the Esso Motor Hotel (opened 1972) and Wembley Conference Centre (opened 31 January 1977), Wembley Exhibition Centre (opened 1977), the 722m2 Greenwich Rooms and a futuristic triangular office block called Elvin House.[109][110] The redevelopment scheme cost £15 million and was designed by R. Seifert & Partners, with Douglas Kershaw and Co. acting as consultant surveyors. Planning consent was given prior to 26 September 1972, after seeking guidance from the Greater London Council, the London Borough of Brent and the Metropolitan Police.[111]

The development included two pedestrian walkways (pedways), allowing people entering and leaving the Stadium to be segregated from the vehicular traffic. The main walkway, which led to Olympic Way, and is still in existence, was 60 feet wide, while another lead to other leading to Empire Way via Elvin House, was 30 feet wide. The Stadium authorities had long been aware of the need for traffic and pedestrian segregation. The main pedway opened in 1975. It has been written, in a 1999 Heritage Study connected with the construction of the new Stadium, that the pedway compromised the north frontage of the 1923 Stadium by obscuring portions of it.[111][112]

Wembley Hill station was called Wembley Complex from May 1978 to May 1987, when it became Wembley Stadium.

In the early 1990s two further exhibition halls were built, offering 17,000m2 of space in all.

Papal visit. 1982

The first open-air mass held during Pope John Paul II's visit to Britain in 1982 was held at Wembley Stadium, on Saturday 29 May. About 80,000 people were present. Archbishop of Westminster Cardinal Basil Hume said that the Stadium had become a church.[113]

Live Aid, 1985

On 13 July 1985 the Stadium was the venue for an enormous 16-hour charity rock concert, largely the brain-child of Irish singer Bob Geldof, in partnership with Midge Ure from Ultravox. Shocked by the famine in Ethiopia, Geldof had created Band Aid, which had released the single Do They Know It’s Christmas/Feed The World in late 1984. Now he had helped arrange a live charity event on an as yet unheard-of scale. As Geldof later said "Wembley had to be the centrepiece: for the thing to have any authority it had to be staged at Wembley." It was held simultaneously with John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia, USA.

Despite organisational problems the event was a huge success.[114]

Over 70,000 saw it live, and a further 1.9 billion watched on television, worldwide. £30 million was raised for famine relief. It was a hot day, and Wembley staff had to distribute water, hose down the crowd and even cut off the legs from people’s jeans to convert them into shorts.[115][116]

Geldof and his band, The Boomtown Rats, had never played at Wembley before, and were astonished by the noise.[114]

The Arena and the Conference Centre and exhibition halls also played their part, being taken over to provide dressing rooms for the performers.[117]

According to Charlie Shun, a Wembley sales manager, Live Aid was "the event which established Wembley [Stadium] as a major rock venue. We had only staged ten different music shows at the stadium before Live Aid but after that it all took off."[118]

Nelson Mandela

On 11 June 1988 a concert was held celebrating the 70th birthday of Nelson Mandela, then a political prisoner. Nearly two years later, on 16 April 1990, only two months after his release, Mandela was present at another Wembley Stadium concert - Nelson Mandela: An International Tribute for a Free South Africa.[119]

Euro '96

In 1996 England hosted the European Championships for the first time. As in 1966, the opening match, England v. Switzerland, took place at Wembley. Played on 8 June 1996, it was a 1 – 1 draw.

England topped their group, and won a quarter final against Spain. This was Wembley's first international penalty shoot-out. The England supporters sang the catchy Euro '96 anthem, Football's Coming Home, but on the following Wednesday, 26 June 1996, in Wembley's second international penalty shoot-out, Germany beat England 6 – 5. Germany went on to beat the Czech Republic 2 – 1 in the final.[120][121]

Wembley Park station was also partially refurbished for Euro '96.[122]

Construction of new stadium

By the 1990s, the 1923 stadium was becoming increasingly outdated. As Conservative MP Andrew Bingham later said in a House of Commons debate on football governance, "I remember going to the last game at the old Wembley stadium and thinking how old and archaic it looked compared with the new and modern grounds."[123]

The Stadium closed in October 2000 and was demolished in 2003.[124] While Wembley was being rebuilt the FA cup finals were played at Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium.[125]

A new Wembley stadium was designed by a consortium including engineering consultant Mott MacDonald and built by the Australian firm Multiplex. It cost £798 million.[124][125]

The new Stadium opened on 17 March 2007 with a Community Day for London Borough of Brent residents.[126]

English alternative rock band Muse became the first popular musicians to perform in the new Stadium, on 16 June 2007. This, their HAARP tour, was voted Wembley’s Greatest Event in 2011.[125][127]

Redevelopment

Mass re-development has occurred in the complex area since the start of the 21st century. The old Wembley Stadium was demolished in 2003 and rebuilt, followed by new developments nearby that continue until the present day. The plans for the redevelopment were approved by the council in June 2004.

Chalkhill estate was already renovated before, in the 1990s.

The remaining portions of the British Empire Exhibition's Palace of Arts were demolished in 2006. The only surviving Exhibition structure, the Palace of Industry, was finally demolished in February–March 2013. A lion's head corbel from the building was saved and is now on display in the green space on Wembley Hill Road, opposite York House.[128] The former Wembley Conference Centre, and the Elvin House block, were also demolished in September 2006.[129] Also in 2006, Wembley Arena, was refurbished at a cost of £34m and its entrance turned around to open onto a new public square with a fountain facing the new Wembley Stadium which then opened in 2007.

At the same time as the new stadium was being built, the old concrete footbridge at Wembley Stadium station, probably built for the British Empire Exhibition, was replaced by a new bridge and a public square. In 2005, after a BBC Five Live poll, it was decided to name the bridge the White Horse Bridge, after PC Scorey’s famous mount. The bridge and square opened in 2008.[130][131]

Wembley Park Sports Ground was located on Bridge Road, near the local station. In 2008 the site was closed down by the council and sold amid protests from locals. It was turned into an academic school with the building mostly completed by 2011.[132]

Developers Quintain and Family Mosaic have led new developments in the area, including residential Forum House completed in 2008 and Quadrant Court in March 2010. Demolition of Malcolm and Fulton House also took place that month. Later work began on the Wembley Park Boulevard leisure and retail hub, including a Hilton Hotel and an outlet shopping centre, the London Designer Outlet (LDO), which opened in August 2013. The development included Market Square and an open space, Wembley Lawns, centred at the Boulevard, and includes a children's playground.

A civic centre was also built at Engineers Way serving as the new home of Brent's local authority. Brent Town Hall, the former home of the council located about a mile north, closed down and was sold, turning into a French lycee school that opened in September 2015. The Town Hall Library was also replaced by a new library adjoined with the civic centre. On Olympic Way, a student accommodation building ran by Victoria Hall Limited was opened in 2011, followed by a Novotel hotel and other buildings. A Boxpark branch also opened here in 2018.[133]

In 2015, Wembley Park's events programme brought 150,000 to the site to enjoy events from Color Run and Survival of the Fittest to a weekly food market.[134]

In May 2016, controversial regeneration plans in the stadium area were approved by the local council. The £2.5 billion scheme from Quintain involves the building of over 7,000 apartments, as well as new shops and offices, two hotels, a 7-acre public park, and a school. There will be a total of seven residential and retail tower blocks, up to 19 storeys high. The plans were disapproved by the Football Association (FA) and by many locals, who claim increased overcrowding and spoilt stadium views. A local launched a petition against these plans to Brent North MP Barry Gardiner and the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan.[135][136][137] however the plans were approved nonetheless.

Quintain unveiled plans for a further 250,000 square feet of retail space in the area in March 2018.[138]

Geography

Barn Hill is 86 metres above sea level, and is part of the larger Fryent Country Park that continues towards Kingsbury. In addition, Wembley Hill Road is a steep road west of Wembley Park, which peaks at around 65 metres above sea level near The Green Man pub.

The Wealdstone Brook tributary of the River Brent starts off at the Stadium Industrial Estate and runs between Bridge Road and Wembley Park Drive, and through Forty Avenue towards Preston. Bridge Road is so-called for the bridge over the narrow brook.

Notable places

An Orthodox Jewish synagogue Wembley United Synagogue is in Forty Avenue. Next to it is the Church of England St. Augustine's Church. A United Reformed Church is on the opposite side, past The Broadway intersection. There is a Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on Wembley Park Drive.

Schools in the area include: Ark Academy, Preston Manor High School, College of North West London, and Lycée International de Londres Winston Churchill.

Notable people

Nearby areas

Transport

Trains

Stations in the area are:

Buses

London Buses routes 83, 92, 182, 206, 223, 245 and 297 serve the area. Uno's 644 bus route terminated at Wembley Park from 2011 until being cut back to Queensbury in March 2016.

References

- "Distance between Wembley, United Kingdom and Wembley Park, Wembley, United Kingdom, (UK)". distancecalculator.globefeed.com.

- Jeff Hill, Francesco Varrasi. "Creating Wembley: The Construction of a National Monument". The Sports Historian. 17 (2). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.557.5566.

- "Harrow, including Pinner : Manors | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 158–60.

- Grant, Philip. "Wembley Park – its story up to 1922" (PDF). Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 155, 161.

- Williams, Cunnington and Hewlett, Leslie R., Win and Geoffrey (1985). "Evidence for a Surviving Humphry Repton Landscape: Barnhills Park, Wembley". Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 36: 189–202. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "London Gardens Online". www.londongardensonline.org.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. p. 162.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. p. 159.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 164–5.

- "Check out this property for sale on Rightmove!". Rightmove.co.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 166–9, 173.

- Hodgkins, David (2002). The Second Railway King: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901. Merton Priory Press. pp. 596–7. ISBN 1898937494.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 170–3.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey. A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 167–9.

- Greaves, John Neville (2005). Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901 The Last of the Railway Kings. Book Guild Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 1857768884.

- Greaves, John Neville (2005). Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901 The Last of the Railway Kings. Book Guild Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 1857768884.

- Hodgkins, David (2002). The Second Railway King: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901. Merton Priory Press. p. 652. ISBN 1898937494.

- "southbank publishing - Metro-Land - British Empire Exhibition 1924 Edition". www.southbankpublishing.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Rowley, Trevor (2006). The English Landscape in the Twentieth Century. Hambledon Continuum. pp. 405–7. ISBN 1852853883.

- "2007 November 19 « The Bioscope". Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Llewellyn, John. "Wembley Park Golf Club, Greater London". www.golfsmissinglinks.co.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Barres-Baker, M.C. "Places in Brent Wembley and Tokyngton" (PDF). Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Elsley, H.W.R. (1953). Wembley through the Ages. Wembley News. p. 148.

- "British Empire Exhibitions 1924-1925 | Explore 20th Century London". www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Knight & Sabey, Donald R. & Alan (1984). The Lion Roars at Wembley. Donald R. Knight. pp. passim.

- Hill and Varrasi, Jeff and Francesco. "Creating Wembley: The Construction of a National Monument" (PDF). Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Clarke, Barbara (2011). "Wembley Stadium – Old and New" (PDF). Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 178–9.

- James, Mark (2013). Sports Law. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 185. ISBN 978-1137026446.

- Knight & Sabey, Donald R. & Alan (1984). The Lion Roars at Wembley. Donald R. Knight. pp. 87–8, 93.

- India : souvenir of the Indian Pavilion and its exhibits. Wembley: British Empire Exhibition. 1924.

- Vijayaraghavacharya, T. (1925). The British Empire Exhibition, 1924. Report by the Commissioner for India for the British Empire Exhibition. Calcutta: Government of India.

- "The Impressive History of the Oldest Indian Restaurant in London That Just Received a Michelin Star". The Better India. 19 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Veeraswamy - London : a Michelin Guide restaurant". www.viamichelin.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Green, Oliver (2015). Metro-Land: 1924 Edition. Southbank Publishing. pp. ix.

- Forrest, Adam (10 September 2015). "Metroland, 100 years on: what's become of England's original vision of suburbia?". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Green, Oliver (2015). Metro-Land: 1924 Edition. Southbank Publishing. pp. v, xv, xxii.

- Jackson, Alan (1986). London's Metropolitan Railway. David & Charles. p. 240. ISBN 0715388398.

- "Metro-Land | Explore 20th Century London". www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Green, Oliver (2015). Metro-Land: 1924 Edition. Southbank Publishing. pp. 36–9.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. p. 215.

- Green, Oliver (2015). Metro-Land: 1924 Edition. Southbank Publishing. pp. xx.

- "Capitol Cinema in Wembley, GB - Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 218–9.

- "Studio Story 1". 30 March 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "the studiotour.com - Wembley Park Studios - History". www.thestudiotour.com. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Schreuders, Lewisohn & Smith, Piet, Mark & Adam (2008). The Beatles' London: The Ultimate Guide to Over 400 Beatles Sites in and Around London. Portico. pp. 167–8. ISBN 978-1906032265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Beatles Bible - Television: Around The Beatles". 28 April 1964. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- team, Code8. "On screen - WEMBLEY PARK". Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Fountain Studios set to close - TVBEurope". 18 January 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Brand new theatre announced for Wembley Park". www.quintain.co.uk. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Troubadour Theatres Limited". www.troubadourtheatres.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 220–2.

- "The Empire Pool, Wembley - Hurst Peirce + Malcolm". hurstpm.net. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Knight and Sabey, Donald R. and Alan (1984). The Lion Roars at Wembley. Donald R. Knight. p. 147.

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. pp. passim.

- Barres-Baker, Malcolm. "A Brief Architectural History of Wembley (later Brent) Town Hall" (PDF). Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Our History - Lycee International de Londres". www.lyceeinternational.london. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Raffray, Nathalie (19 September 2015). "French school Lycee Internationale de Londres Winston Churchill opens in Wembley". Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Low, A. M. (1953). Wonderful Wembley. Stanley Paul. p. 139.

- Dictionary of National Biography (Arthur Elvin).

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. p. 12.

- JISC., University of Portsmouth, in collaboration with the National Archives and funded by. "Bomb Sight - Mapping the London Blitz". Bomb Sight. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Low, A. M. Wonderful Wembley. Stanley Paul. pp. 144–5.

- Unexploded Second World War bomb near Wembley Stadium poses 'genuine risk to life', archived from the original on 24 May 2015, retrieved 22 July 2016

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. p. 235.

- "The List of Victory International Matches". www.sirbillywright.com. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Low, A. M. (1953). Wonderful Wembley. Stanley Paul. p. 11.

- The Official Report of the Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. The Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. 1948. p. 17.

- "London 1948 Olympic Games". Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- shannen.bradley (12 March 2013). "1948 London Olympics". Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

The 1948 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XIV Olympiad, were the first since the Berlin Games of 1936.

- "Former Norwich paperboy was a driving force behind 1948 London Olympics". 24 July 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Wembley, London Borough of Brent". www.brent-heritage.co.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "'Wembley Way' built by German PoWs". BBC. 15 March 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Wembley Stadium | stadium, London, United Kingdom". Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "County was on track for Olympics". 2 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- shannen.bradley (12 March 2013). "1948 London Olympics". Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Dudley, G. (2011). The Outer Cabinet: A History of the Government Car Service. Government Car and Despatch Agency. pp. 48–9.

- Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad (1948). The Official Report of the Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. The Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. p. 22.

- Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad (1948). The Official Report of the Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. The Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. p. 49.

- "International Olympics-Olympic Heroes". internationalolympics-olympicheroes.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad (1948). The Official Report of the Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. The Organising Committee for the XIV Olympiad. pp. 278, 282, 284.

- Knight & Sabey, Donald R. & Alan (1984). The Lion Roars at Wembley. Donald R. Knight. pp. 142–3.

- Knight & Sabey, Donald R. & Alan (1984). The Lion Roars at Wembley. Donald R. Knight. p. 146.

- Watt & Palmer, Tom & Kevin (1998). Wembley: The Greatest Stage. Simon & Schuster. p. 241.

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. p. 14.

- Low, A.M. (1953). Wonderful Wembley. Stanley Paul. p. 157.

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. p. 15.

- "On This Day: Henry Cooper dropped Muhammad Ali at Wembley Stadium - Boxing News". 18 June 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Watt & Palmer, Tom & Kevin (1998). Wembley: The Greatest Stage. Simon & Schuster. p. 172.

- "1966 Review of the Year" (PDF). Greyhound Racing History. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "England in the World Cup - 1966 Final Tournament". www.englandfootballonline.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Watt & Palmer, Tom & Kevin (1998). Wembley: The Greatest Stage. Simon & Schuster. pp. 171–9.

- "They think it's all over « England Memories". englandmemories.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Manchester United 1967-1968 European Cup Final Line up". www.mufcinfo.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. p. 19.

- "The Beatles Bible - NME Poll-Winners' show: The Beatles' final UK concert". May 1966. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. p. 18.

- "07/13/1969 Wembley, United Kingdom". forgotten-yesterdays.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "The Ultimate Gig List - Accompanying Notes". www.leehawkins.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Clifton, Peter (1 December 1973), The London Rock and Roll Show, retrieved 14 August 2016

- Watt & Palmer, Tom & Kevin (1998). Wembley: The Greatest Stage. Simon & Schuster. p. 265.

- "Crosby Stills Nash and Young - Wembley Stadium 1974". www.ukrockfestivals.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "The Who- Wembley Stadium 1979". www.ukrockfestivals.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. pp. 20–1.

- "The Space at Westbury". www.thespaceatwestbury.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. p. 222.

- Bass, Howard (1982). Glorious Wembley. Guinness Superlatives. pp. 157–8.

- Wembley Stadium Limited Development Scheme. Wembley Stadium Limited. 1972.

- Wembley: New English National Stadium Planning and Listed Building Consent Applications Heritage Study. Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners. 1999.

- Systems, eZ. "Wembley Stadium / A Retrospective of the 1982 Visit / Visit Background / Home - The Visit". www.thepapalvisit.org.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Watt & Palmer, Tom & Kevin (1998). Wembley: The Greatest Stage. Simon & Schuster. pp. 261–4.

- "1985: Was Live Aid the best rock concert ever?". BBC. 13 July 1985. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "CNN.com - Live Aid 1985: A day of magic - Jul 1, 2005". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Wembley Arena 1934-2004 The First Seventy Years. Wembley Arena. 2004. p. 24.

- Watt & Palmer, Tom & Kevin (1998). Wembley: The Greatest Stage. Simon & Schuster. p. 266.

- Gibson, Megan. "Highlights From Nelson Mandela's 1990 Appearance at London Wembley's Charity Concert". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Watt & Palmer, Tom & Kevin (1998). Wembley: The Greatest Stage. Simon & Schuster. pp. 289–95.

- "Euro 1996 fixture". Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Wembley Park Station, ready on time!". www.railwaypeople.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 09 Feb 2012 (pt 0001)". www.publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Wembley: Towers to arches". New Civil Engineer. 22 December 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Stadium, Wembley. "90 Years Of Wembley Stadium | Wembley Stadium". www.wembleystadium.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Doors finally open at new Wembley". BBC. 17 March 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Muse HAARP tour voted Wembley's Greatest Event [Archive] - Muse Messageboard". board.muse.mu. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Proctor, Ian (31 July 2014). "Lion head from old Palace of Industry in Wembley opened on plinth". Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "Media file" (PDF). www.quintain.co.uk. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- "Wembley bridge named White Horse". BBC. 24 May 2005. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Marks Barfield Architects". Marks Barfield. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Teachers against Wembley Academy resist Brent Council eviction of 'Tent City' - UK Indymedia". www.indymedia.org.uk.

- "Boxpark Wembley Is Happening". Londonist. 16 February 2018.

- team, Code8. "Events & entertainment - WEMBLEY PARK". Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "Plans approved for £2.5bn regeneration around Wembley Stadium". Property Investor Today.

- "£2.5bn regeneration around Wembley Stadium gets green light". Evening Standard. 12 May 2016.

- "Wembley Stadium tower block plan 'would risk fans' safety'". Evening Standard. 11 May 2016.

- "Next stage launched in massive £3 billion Wembley Park regeneration". Evening Standard. 7 March 2018.