Voice onset time

In phonetics, voice onset time (VOT) is a feature of the production of stop consonants. It is defined as the length of time that passes between the release of a stop consonant and the onset of voicing, the vibration of the vocal folds, or, according to other authors, periodicity. Some authors allow negative values to mark voicing that begins during the period of articulatory closure for the consonant and continues in the release, for those unaspirated voiced stops in which there is no voicing present at the instant of articulatory closure.

History

The concept of voice onset time can be traced back as far as the 19th century, when Adjarian (1899: 119)[1] studied the Armenian stops, and characterized them by "the relation that exists between two moments: the one when the consonant bursts when the air is released out of the mouth, or explosion, and the one when the larynx starts vibrating". However, the concept became "popular" only in the 1960s, in a context described by Lin & Wang (2011: 514):[2] "At that time, there was an ongoing debate about which phonetic attribute would allow voiced and voiceless stops to be effectively distinguished. For instance, voicing, aspiration, and articulatory force were some of the attributes being studied regularly. In English, "voicing" can successfully separate /b, d, ɡ/ from /p, t, k/ when stops are at word-medial positions, but this is not always true for word-initial stops. Strictly speaking, word-initial voiced stops /b, d, ɡ/ are only partially voiced, and sometimes are even voiceless." The concept of VOT finally acquired its name in the famous study of Leigh Lisker and Arthur Abramson (Word, 1964), done while working together at Haskins Laboratories.[3]

Analytic problems

A number of problems arose in defining VOT in some languages, and there is a call for reconsidering whether this speech synthesis parameter should be used to replace articulatory or aerodynamic model parameters which do not have these problems, and which have a stronger explanatory significance.[4] As in the discussion below, any explication of VOT variations will invariably lead back to such aerodynamic and articulatory concepts, and there is no reason presented why VOT adds to an analysis, other than that, as an acoustic parameter, it may sometimes be easier to measure than an aerodynamic parameter (pressure or airflow) or an articulatory parameter (closure interval or the duration, extent and timing of a vocal fold abductory gesture).

Types

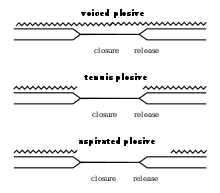

Three major phonation types of stops can be analyzed in terms of their voice onset time.

- Simple unaspirated voiceless stops, sometimes called "tenuis" stops, have a voice onset time at or near zero, meaning that the voicing of a following sonorant (such as a vowel) begins at or near to when the stop is released. (An offset of 15 ms or less on [t] and 30 ms or less on [k] is inaudible, and counts as tenuis.)

- Aspirated stops followed by a sonorant have a voice onset time greater than this amount, called a positive VOT. The length of the VOT in such cases is a practical measure of aspiration: The longer the VOT, the stronger the aspiration. In Navajo, for example, which is strongly aspirated, the aspiration (and therefore the VOT) lasts twice as long as it does in English: 160ms vs. 80ms for [kʰ], and 45ms for [k]. Some languages have weaker aspiration than English. For velar stops, tenuis [k] typically has a VOT of 20-30 ms, weakly aspirated [k] of some 50-60 ms, moderately aspirated [kʰ] averages 80–90 ms, and anything much over 100 ms would be considered strong aspiration. (Another phonation, breathy voice, is commonly called voiced aspiration; in order for the VOT measure to apply to it, VOT needs to be understood as the onset of modal voicing. Of course, an aspirated consonant will not always be followed by a voiced sound, in which case VOT cannot be used to measure it.)

- Voiced stops have a voice onset time noticeably less than zero, a "negative VOT", meaning the vocal cords start vibrating before the stop is released. With a "fully voiced stop", the VOT coincides with the onset of the stop; with a "partially voiced stop", such as English [b, d, ɡ] in initial position, voicing begins sometime during the closure (occlusion) of the consonant.

Because neither aspiration nor voicing is absolute, with intermediate degrees of both, the relative terms fortis and lenis are often used to describe a binary opposition between a series of consonants with higher (more positive) VOT, defined as fortis, and a second series with lower (more negative) VOT, defined as lenis. Of course, being relative, what fortis and lenis mean in one language will not in general correspond to what they mean in another.

Voicing contrast applies to all types of consonants, but aspiration is generally only a feature of stops and affricates.

Transcription

Aspiration may be transcribed ⟨◌ʰ⟩, long (strong) aspiration ⟨◌ʰʰ⟩. Voicing is most commonly indicated by the choice of consonant letter. For one way of transcribing pre-voicing and other timing variants, see extensions to the IPA#Diacritics. Other systems include that of Laver (1994),[5] who distinguishes fully devoiced ⟨b̥a⟩ and ⟨ab̥⟩ from initial partial devoicing of the onset of a syllable by ⟨˳ba⟩ and from final partial devoicing of the coda of a syllable by ⟨ab˳⟩.

Examples in languages

| Voice Onset Time | Examples | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Cantonese | Tlingit | Navajo | Korean | Japanese | Spanish, Russian | Thai, Armenian | ||||

| (fortis) | Strong aspiration | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| ↑ | Moderate aspiration | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Mild aspiration | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||

| Tenuis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| ↓ | Partially voiced | Yes | |||||||||

| (lenis) | Fully voiced | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

Publications

- Abramson, A., & Lisker, L. (1973). Voice timing perception in Spanish word-initial stops. Journal of Phonetics, 1, 1-8.

- Abramson, A. S., & Whalen, D. H. (2017). Voice Onset Time (VOT) at 50: Theoretical and practical issues in measuring voicing distinctions. Journal of Phonetics, 63, 75–86.

- Allen, J., Miller, J., & DeSteno, D. (2003). Individual talker differences in voice-onset-time. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 113, 544–552.

- Cho, T., & Ladefoged, P. (1999). Variation and universals in VOT: Evidence from 18 languages. Journal of Phonetics, 27, 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1006/jpho.1999.0094

- Cho, T., Whalen, D., & Docherty, G. (2019). Voice onset time and beyond: Exploring laryngeal contrast in 19 languages. Journal of Phonetics, 72, 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wocn.2018.11.002

- Itoh, M., Sasanuma, S., Tatsumi, I. F., Murakami, S., Fukusako, Y., & Suzuki, T. (1982). Voice onset time characteristics in apraxia of speech. Brain and Language, 17, 193–210.

- Kessinger, R. H., & Blumstein, S. E. (1997). Effects of speaking rate on voice-onset time in Thai, French, and English. Journal of Phonetics, 25, 143–168

- Lisker, L., & Abramson, A. S. (1964). A cross-language study of voicing in initial stops: Acoustical measurements. Word, 20(3), 384–422. DOI: 10.1080/00437956.1964.11659830.

- Rubin, P. (2022). Arthur Abramson. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, April 20, 2022. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.923

- Scobbie, J. M. (2006). Flexibility in the face of incompatible English VOT systems. In L. Goldstein, D. H. Whalen, & C. T. Best (Eds.), Laboratory phonology 8: Varieties of phonological competence (pp. 367–392). Papers from 8th Conference on Laboratory Phonology, New Haven, CT. Phonology and Phonetics 4. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Winn, M. B. (2020). Manipulation of voice onset time in speech stimuli: A tutorial and flexible Praat script. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 147, 852-866.

References

- ADJARIAN, H., Les explosives de l'ancien arménien étudiées dans les dialectes modernes, La Parole. Revue internationale de Rhinologie, Otologie, Laryngologie et Phonétique expérimentale, 119-127 (1899) "... la relation qui existe entre deux moments : celui où la consonne éclate par l'effet de l'expulsion de l'air hors de la bouche, ou explosion, et celui où le larynx entre en vibration."

- LIN, C. & WANG, H., Automatic estimation of voice onset time for word-initial stops by applying random forest to onset detection, The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 514-525 (2011)

- "Lisker, L. and Abramson, A.S., A cross-language study of voicing in initial stops: acoustical measurements, Word Vol. 20, 384-422 (1964)" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-07-02.

- ROTHENBERG, M. "Voice Onset Time vs. Articulatory Modeling for Stop Consonants", The Jan Gauffin Memorial Symposium, October 16, 2008. Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. (To be published in the proceedings)

- Principles of Phonetics, p. 340

Sources

- Taehong Cho and Peter Ladefoged, "Variations and universals in VOT: Evidence from 18 languages". Journal of Phonetics vol. 27. 207-229. 1999.

- Angelika Braun, "VOT im 19. Jahrhundert oder "Die Wiederkehr des Gleichen"". Phonetica vol. 40. 323-327. 1983.

External links

- Abramson-Lisker VOT Stimuli. An interactive demo of VOT stimuli created by Arthur Abramson and Leigh Lisker

- Buy a pie for the spy A description of the mechanism of voiced, tenuis (voiceless unaspirated), and (voiceless) aspirated stops in relation to voice onset time