Vincent Schofield Wickham

Vincent Schofield Wickham (1894-1968) was a New York graphic illustrator, painter, sculptor, teacher, and inventor, whose career coincided with the Golden Age of American Illustration.[1] Wickham worked as an editorial artist for the New York Times from 1924-1956. His work included sports illustrations, window displays in Times Square, and promotional posters that were displayed on newspaper trucks. In addition to his job at NYT, he also taught advertising art and layout at Textile Evening High School (now the Bayard Rustin Educational Complex), on 351 West 18th Street.[1]

Vincent Schofield Wickham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 29, 1894 Worcester, MA |

| Died | December 9, 1968 New London, NH |

| Occupation(s) | Editorial artist, sculptor |

Early career

In 1917, Wickham received a degree in Modeling and Sculpture from Massachusetts Normal Art School,[2] (now Massachusetts College of Art and Design).[1] The same year, he apprenticed under renowned sculptor, and fellow Worcester native, Andrew O'Connor. Being the "slimmest of the students," Wickham was O'Connor's model for the Spanish War Memorial statue, 1898 Soldier (image), still on display in Worcester's Wheaton Square.[3] Before his career as an editorial artist, Wickham invented orthodontal devices, including a "trimmer for bad teeth," and an "Apparatus for Trimming Ondontological Casts," for which he received a US patent (Mar. 21, 1919).[4][5]

Guayas River, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 1936.

Guayas River, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 1936. Cusco, Mexico, 1936.

Cusco, Mexico, 1936. Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1936.

Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1936. Bronze plaque of Antarctic explorer Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, presented to the American Geographical Society, 1929.

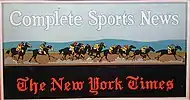

Bronze plaque of Antarctic explorer Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, presented to the American Geographical Society, 1929. Vincent Schofield Wickham Complete Sports News Rotogravure.

Vincent Schofield Wickham Complete Sports News Rotogravure. Art print by Vincent Schofield Wickham, in Racing News, New York Times.

Art print by Vincent Schofield Wickham, in Racing News, New York Times.

Sculptor, graphic illustrator, poet

As a sculptor, Wickham was sought out and commissioned for projects. He struck the die for plaster casts commemorating the 160th anniversary of the American Whig Society, and the 50th anniversary of the graduation of Woodrow Wilson from Princeton University. These casts were unveiled at the Whig-Wilson Anniversary Celebration, held at Princeton by the American Whig–Cliosophic Society, on December 11, 1929.[6] George Washington Ochs-Oakes (George Oakes), founder of Current History Magazine (and brother of New York Times founder Adolph Ochs), attended the unveiling. In a letter dated December 13, 1929, Ochs-Oakes congratulates Wickham "on the enthusiasm with which your medal was received at Princeton. I was down there the other night and everybody admired it very much."[7]

Following the commemoration, Wickham sent several plaster replicas of the medallion to Whig Society members who attended Princeton during Wilson's tenure as professor, and president of the University. These recipients include: George S. Cunningham, of Mission Hospital, Dumaguete, Philippine Islands; Zeph. Chas. Felt (graduated Princeton 1879), a real estate and loan magnate in Denver, CO; Sumner Walters (graduated 1919), of Church of the Redeemer, St. Louis, MO; Dr. Jose Romero (had Wilson as a professor in 1892 and 1895) of Washington, DC; John L. Porter, Pittsburgh businessman, philanthropist and arts advocate; H.C. Adler, Manager of the Chattanooga Times.[8]

In a letter dated Jan. 20, 1930, poet Rev. Seth Russell Downie, chaplain of the Pennsylvania State Fireman's Association, writes an especially prosaic letter to Wickham, about finding the "wee hangerhook" of the medallion "too much below rim to admit of use over nail or hook. But, my good sir, this merely gave me chance to use a nifty orange and black ribbonbow to neatly carry out the atmosphere of Old Nassau 'gainst the nooky spot on the homey wall of the living room." In closing, Rev. Downie praises Woodrow Wilson in heroic fashion: "At this very time, our beloved idealist will command the world's acknowledgement as one who clearly envisaged the great society of Nations among whom Justice should reign & peace prevail. In every corner of the earth — our idol will be blessed. The excoriated will be exalted. That will be glory enough for us — My dear sir — glory and good news."[9]

1929 was a busy year for Wickham, as he was also commissioned by the American Geographical Society for a medallion commemorating aviator and Antarctic explorer Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd. Six years later, in 1935, Wickham sent the original model of this medallion to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Inspired by words as well as images, Wickham's poem, "A Bookplate Speaks," originally published in the New York Times, anthropomorphizes steel engraving printmaking, and showcases the artist's facility with language:

- Although begot of polished, graven steel,

- Entombed within thy lines do I conceal

- A soul; 'twere better were I ruby red,

- Perhaps, instead of black, so dead,

- For then, his every heartbeat I might feel

- And breathe and speak and tell the ardent zeal

- With which he studied, mastered every line

- Embodied in my quaint, beloved design.

- Thus now you well might look and long review

- Your bookplate; for the master's hand that drew

- This something which is me, for you to hold

- He, too, regarded me far more than gold

- Search long and well for him whose spirit lies

- Within my lines, in raven black disguise.[10]

Graphic illustration for the New York Times.

Graphic illustration for the New York Times. Truck displaying baseball graphic illustration by Vincent Schofield Wickham.

Truck displaying baseball graphic illustration by Vincent Schofield Wickham. Chattanooga Citizen Emeritus, July 2, 1926. Adolph Ochs

Chattanooga Citizen Emeritus, July 2, 1926. Adolph Ochs Photograph of Sports feature.

Photograph of Sports feature. Illustrations displayed in the studio of the artist.

Illustrations displayed in the studio of the artist.

Personal life

Wickham was married twice, first to Dorothy Callan (1908-1948; widowed), with whom he fathered two children, Vincent Jr. (1938-2000), and Sally Wickham Mollomo (1943—2020); and Vivian Mallett Roberge (1900-1984). A man of adventure, Wickham and his first wife, Dorothy Callan, took excursions by steamship to Peru, Cuba, and Bermuda. They also were members of the Old White Art Colony at White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, where they attended a charity dinner dance on August 23, 1939.[11] A lifelong learner, Wickham earned a Bachelor of Arts from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Department of Education, in 1957, at age 63.[1] Retiring to New London, New Hampshire, Wickham studied and wrote poetry, and continued teaching art. His reputation preceded him, and even in retirement he was commissioned to design emblems, including the New London Town Seal. The Vincent Schofield Wickham Collection, curated by Massachusetts College of Art and Design's Archives and Special Collections Department, includes several of Wickham's watercolors, as well as historical photographs from his tenure at the New York Times.

Medallion commemorating the 50th Anniversary of Woodrow Wilson's graduation from Princeton University. Presented by the American Whig Society, 1929.

Medallion commemorating the 50th Anniversary of Woodrow Wilson's graduation from Princeton University. Presented by the American Whig Society, 1929. A letter from President Roosevelt, thanking Mr. Wickham for submitting his original model of Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

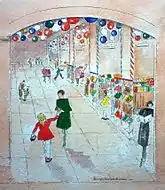

A letter from President Roosevelt, thanking Mr. Wickham for submitting his original model of Admiral Richard E. Byrd. New York Times Book Fair, c. 1940.

New York Times Book Fair, c. 1940. Photograph of bas-relief.

Photograph of bas-relief. Taxco, Mexico (with notes by the artist).

Taxco, Mexico (with notes by the artist).

References

- "Vincent Wickham, Retired Artist, 74". New York Times. December 10, 1968.

- Graduation Exercises of the Massachusetts Normal Art School, 1917

- Soderman, Doris Flodin (1995). The Sculptors O'Connor. Worcester, MA: Gundi Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-9642863-0-0.

- "Invents "Trimmer" for Bad Teeth". Boston Herald. 1924.

- Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office. United States, Patent Office. p. 465. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

vincent schofield wickham.

- "Whig Anniversary Guests to Receive Memorial Plaques". Daily Princetonian. December 10, 1929. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Ochs-Oakes, George. ""Letter to Vincent S. Wickham"" (December 13, 1929). The Vincent Schofield Wickham Collection. Boston: Archives and Special Collections Department, Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

- ""Letters to Vincent S. Wickham from recipients of the Woodrow Wilson medallion"" (1930). The Vincent Schofield Wickham Collection. Boston: Archives and Special Collections Department, Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

- Russell Downie, Seth. ""Letter to Vincent S. Wickham"" (January 20, 1930). The Vincent Schofield Wickham Collection. Boston: Archives and Special Collections Department, Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

- "A Bookplate Speaks". The Free-Lance Star. January 31, 1940.

- "Charity Fete Held at White Sulphur". The New York Times. August 23, 1939.