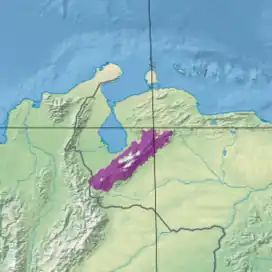

Venezuelan Andes montane forests

The Venezuelan Andes montane forests (NT0175) is an ecoregion in the northern arm of the Andes in Venezuela. It contains montane and cloud forests, reaching up to the high-level Cordillera de Merida páramo high moor ecoregion. The forests are home to many endemic species of flora and fauna. Their lower levels are threatened by migrant farmers, who clear patches of forest to grow crops, then move on.

| Venezuelan Andes montane forests (NT0175) | |

|---|---|

| |

Ecoregion territory (in purple) | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Neotropical |

| Biome | tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests |

| Borders | |

| Geography | |

| Area | 29,526 km2 (11,400 sq mi) |

| Countries | |

| Coordinates | 9.357°N 70.237°W |

| Climate type | Cfb: warm temperate, fully humid, warm summer |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Vulnerable |

Geography

Location

The Venezuelan Andes montane forests ecoregion covers most of the Venezuelan states of Mérida and Trujillo, much the state of Táchira and the highlands of the states of Lara and Barinas.[1] It includes a small area in Colombia. It covers the lower part of the Venezuelan extension of the Cordillera Occidental of the northern Andes. It has an area of 2,952,586 hectares (7,296,000 acres).[2]

To the southeast it adjoins the Llanos and the Apure–Villavicencio dry forests, and to the southwest adjoins the Cordillera Oriental montane forests. To the northwest it adjoins the Catatumbo moist forests and the Maracaibo dry forests. To the north it merges into Paraguana xeric scrub and La Costa xeric shrublands. It contains areas of Cordillera de Merida páramo on the higher ground.[3]

Terrain

The Venezuelan Andes montane forests ecoregion contains the high altitude cloud forests of the Venezuelan Andean Cordillera, which reaches altitudes of 4,000–5,007 metres (13,123–16,427 ft).. This is a northeastern branch of the Andes that is separated from Colombia's Cordillera Oriental by the Táchira depression on the Venezuela–Colombia border. The ecoregion extends from the Táchira depression for about 450 kilometres (280 mi) in a northeast direction to the Barquisimeto depression. The ecoregion also includes the forests of the isolated Tamá Massif, which lies between the Colombian Andes and the Táchira depression.[1]

The mountains were formed during the Paleocene epoch and continued rising until the end of the Pliocene epoch. They are mainly composed of quartzite schist, gneiss and limestone, with isolated intrusions of granite and diabase. The soils are mostly inceptisols, but entisols are often found in slopes and eroded areas. The rivers that form near the summits create large valleys that form physiographical barriers between the ranges of the Cordillera. The largest, the Chama, crosses the northeast–southwest axis of the middle part of the Cordillera, dividing into the Cordillera de Mérida to the south and the Sierra de la Culata to the north. Other major rivers are the Santo Domingo, Boconó and Motatán.[1]

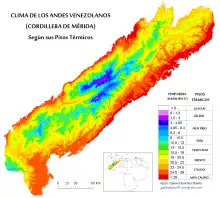

Climate

The Köppen climate classification is "Cfb": warm temperate, fully humid, warm summer.[4] From 800 to 2,500 metres (2,600 to 8,200 ft) in elevation the average annual temperatures are 24–12 °C (75–54 °F). Temperatures are lower above this elevation. The northeastern trade winds strongly affect the climate. There is a dry season from December to April and a wet season from April to November when moisture is carried from the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Average annual rainfall is 2,000 to 3,000 millimetres (79 to 118 in), but varies considerably from place to place. Along the southeastern slopes high rainfall starts above 2,400 metres (7,900 ft), while along the northwest slopes high rainfall starts at 1,200 metres (3,900 ft). Slopes in the interior valleys are dry, and often very dry.[1]

Ecology

The Venezuelan Andes montane forests ecoregion is in the Neotropical realm, in the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome.[2] The ecoregion forms an ecological barrier between the Lake Maracaibo region and the Llanos.[1] It has a great variety of plants, many endemic, and is seen as a plant refuge and dispersal center.[1]

Flora

Vegetation includes evergreen transition forests between 800 metres (2,600 ft) and 1,800–2,000 metres (5,900–6,600 ft) and evergreen cloud forests higher up. The evergreen transition forests are dense, with two or three layers, with most trees of the families Lauraceae, Moraceae, Myrtaceae, Bignoniaceae, Euphorbiaceae and Araliaceae. From 2,000 to 3,000 metres (6,600 to 9,800 ft) there are very dense cloud forests with two or three layers, many epiphytes and a rich understory. Common species are Retrophyllum rospigliosii, Prumnopitys montana, Podocarpus oleifolius, Alnus jorullensis, Oreopanax moritzii, Brunellia integrifolia, Hedyosmum glabratum, Weinmannia jahnii, Weinmannia microphylla, Tetrorchidium rubrivenium, Beilschemieda sulcata, Ruagea glabra and Ruagea pubescens.[1]

The montane forests and páramos of Mérida have 155 endemic plant species, and contains 30% of the ecoregion's endemic flora. The forests and páramos of the isolated Tamá massif have another 82 endemic plant species. Common montane forest endemic plants are Podocarpus pedulifolius, Oreopanax veillonii, Psychotria aristeguiateae, Lagenanthus princeps, Delostoma integrifolium, as well as bromeliad, fern and orchid species.[1]

Fauna

There are four endemic mammal species in the ecoregion. The wood sprite gracile opossum (Gracilinanus dryas) and Luis Manuel's tailless bat (Anoura luismanueli) are found in both the Andean Cordillera and the Tamá Massif. The dressy Oldfield mouse (Thomasomys vestitus) is found only in the Andean Cordillera. Musso's fish-eating rat (Neusticomys mussoi) has been reported for just one place in the Andean Cordillera. Mammal subspecies found only in the montane forests ecoregion and the Cordillera de Mérida Páramo ecoregion include the Andean white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus goudotii), found in the ecotone between the high montane forests and the páramos, and the rufous little red brocket (Mazama rufina bricenii), found in evergreen forest and páramos from 1,000–3,000 metres (3,300–9,800 ft). Both deer species are endangered by hunting.[1]

In the forest margins beside the páramos the crab-eating rat (Ichthyomys hydrobates), which is restricted to the Andes in Venezuela and Colombia, is threatened by changes to its habitat, and the pacarana (Dinomys branickii), widespread in the Andes, is threatened by hunting. The endangered spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) is found throughout the Andes from Bolivia to Venezuela. In Venezuela it is found between 380 and 4,700 metres (1,250 and 15,420 ft) in the Andes and Serranía del Perijá, most often in cloud forests between 1,000 and 3,000 metres (3,300 and 9,800 ft). It has low rates of reproduction and is threatened by hunting and destruction of habitat.[1] Endangered mammals include Geoffroy's spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi) and Musso's fish-eating rat (Neusticomys mussoi).[5]

.jpg.webp)

25 endemic birds species with restricted ranges are reported in the ecoregion of which four are found only in the montane forest ecoregion. There are fewer species at higher levels and fewest in the páramos. Endemic birds include amethyst-throated sunangel (Heliangelus amethysticollis), grey-capped hemispingus (Hemispingus reyi), white-fronted whitestart (Myioborus albifrons), grey-naped antpitta (Grallaria griseonucha), rose-crowned parakeet (Pyrrhura rhodocephala) and Mérida flowerpiercer (Diglossa gloriosa). Restricted range species in the Tamá massif include Táchira antpitta (Grallaria chthonia), hooded antpitta (Grallaricula cucullata) and Venezuelan wood quail (Odontophorus columbianus).[1] Endangered birds include helmeted curassow (Pauxi pauxi), red siskin (Spinus cucullatus) and black-and-chestnut eagle (Spizaetus isidori).[5]

The salamander species Bolitoglossa orestes is endemic. The ecoregion is rich in endemic frog species, with 62 species in the Cordillera de Mérida alone, many endemic to the cloud forests. The most common families are Eleutherodactylus and Centrolenidae. They live between 2,000 and 3,400 metres (6,600 and 11,200 ft) in the cloud forests and beside streams in very humid páramos.[1] Endangered amphibians include Aromobates alboguttatus, A. duranti, A. haydeeae, A. leopardalis, A. mayorgai, A. meridensis, A. molinarii, A. nocturnus, A. orostoma, A. saltuensis, A. serranus, Atelopus carbonerensis, A. chrysocorallus, A. mucubajiensis, A. oxyrhynchus, A. pinangoi, A. sorianoi, Dendropsophus meridensis, Gastrotheca ovifera, Hyalinobatrachium pallidum, Mannophryne collaris, M. cordilleriana, M. yustizi, Pristimantis ginesi, P. lancinii and P. paramerus.[5]

Status

The World Wildlife Fund gives the ecoregion the status "Vulnerable". The low to mid-altitude montane forests are being invaded by migrant farmers, who fragment the habitat. This is the main threat, but extraction of valuable orchids and bromeliads is also an issue. Requests, so far refused, have been made for permits to mine for zinc, cooper, lead and silver in the Bailadores–Guaraque region, including the General Pablo Peñalosa National Park. Coal mining in the Táchira depression may threaten the adjacent Tamá Masif.[1]

20.78% of the ecoregion is protected. Venezuelan national parks that protect parts of the ecoregion include the Guaramacal National Park, Sierra Nevada National Park, Sierra La Culata National Park, General Juan Pablo Peñaloza National Park, Dinira National Park and Yacambú National Park. The Tamá National Natural Park in Colombia and the El Tamá National Park in Venezuela protect parts of the Tamá Massif. Some of the parks are threatened by sheer numbers of tourists, and by fires and proposed construction of roads and pipelines.[1]

Notes

- Bonaccorso.

- Venezuelan Andes montane forests – Myers, WWF Abstract.

- WildFinder – WWF.

- Venezuelan Andes montane forests – Myers, Climate Data.

- Venezuelan Andes montane forests – Myers, All Endangered.

Sources

- Bonaccorso, Elise, Northern South America: Northwestern Venezuela into Colombia, WWF: World Wildlife Fund, retrieved 2017-04-18

- "Venezuelan Andes montane forests", Global Species, Myers Enterprises II, retrieved 2017-04-18

- WildFinder, WWF: World Wildlife Fund, retrieved 2017-04-17