Velopharyngeal insufficiency

Velopharyngeal insufficiency is a disorder of structure that causes a failure of the velum (soft palate) to close against the posterior pharyngeal wall (back wall of the throat) during speech in order to close off the nose (nasal cavity) during oral speech production. This is important because speech requires sound (from the vocal folds) and airflow (from the lungs) to be directed into the oral cavity (mouth) for the production of all speech sound with the exception of nasal sounds (m, n, and ng). If complete closure does not occur during speech, this can cause hypernasality (a resonance disorder) and/or audible nasal emission during speech (a speech sound disorder). In addition, there may be inadequate airflow to produce most consonants, making them sound weak or omitted.[1]

| Velopharyngeal insufficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | VPI |

| Specialty | Oral and maxillofacial surgery |

The terms "velopharyngeal insufficiency" "velopharyngeal incompetence, "velopharyngeal inadequacy" and "velopharyngeal dysfunction" have often been used interchangeably, although they do not mean the same thing. "Velopharyngeal dysfunction" now refers to abnormality of the velopharyngeal valve, regardless of cause. Velopharyngeal insufficiency includes any structural defect of the velum or mechanical interference with closure. Causes include a history of cleft palate, adenoidectomy, irregular adenoids, cervical spine anomalies, or oral/pharyngeal tumor removal.[2] In contrast, "velopharyngeal incompetence" refers to a neurogenic cause of inadequate velopharyngeal closure. Causes may include stroke, traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy, or neuromuscular disorders.[3] It is important that the term "velopharyngeal insufficiency" is used if it is an anatomical defect and not a neurological problem.[4]

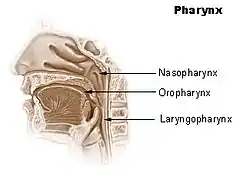

Anatomy

- Nasal cavity

- Hard palate

- Soft palate

- Tongue

- Lips

- Tissue used for surgery

Diagnosis

Speech analysis

Velopharyngeal insufficiency can be diagnosed by a speech pathologist through a perceptual speech assessment. Speech characteristics of VPI include hypernasality (too much sound in the nasal cavity during speech) and/or audible nasal emission of air during speech. Nasal emission can also cause the consonants to be very weak in intensity and pressure. The patient may develop compensatory productions for consonants, where the sounds are produced in the pharynx (throat area) where there is adequate airflow. [5][6]

Nasometry

Nasometry is a method of measuring the acoustic correlates of resonance and velopharyngeal function through a computer-based instrument. Nasometry testing gives the speech pathologist a nasalance score, which is the percentage of nasal sound of the total (nasal plus oral) sound during speech. This score can be compared to normative values for the speech passage. Nasometry is useful in the evaluation of hypernasality because it provides objective measurements of the function of the velopharyngeal valve. As such, it is often used for pre-and post-surgical comparisons and to determine speech outcomes as a result of certain surgical interventions. [7][8]

Nasopharyngoscopy

Nasopharyngoscopy is endoscopic technique in which the physician or speech pathologist passes a small scope through the patient's nose to the nasopharynx. The nasal cavity is typically numbed before the procedure, so there is minimal discomfort. Nasopharyngoscopy provides a view of the velum (soft palate) and pharyngeal walls (walls of the throat) during nasal breathing and during speech. The advantage of this technique over videofluoroscopy is that the examiner can see the size, location, and cause of the velopharyngeal opening very clearly and without harm (e.g., radiation) to the patient. Even very small openings can be visualized. This information is helpful in determining appropriate surgical or prosthetic management for the patient. The disadvantage of this technique is that the vertical level velar elevation is less obvious than with videofluoroscopy, although this is not a big concern. [9][10][11]

Videofluoroscopy

Multiview videofluoroscopy is a radiographic technique to view the length and movement of the velum (soft palate) and the posterior and lateral pharyngeal (throat) walls during speech. The advantage of this technique is that the entire posterior pharyngeal wall can be visualized. Disadvantages include the following: 1. This procedure requires radiation, which is a particular concern for children. 2. It is not well tolerated by some children because it requires injection of barium into the nasopharynx through a nasal catheter. 3. The resolution (clarity of the image) is not nearly as good as nasopharyngoscopy. 4. Small or unilateral openings cannot be seen because the X-ray beam takes a sum of all the parts. 5. It only provides a two-dimensional view, and therefore, multiple views are needed to see the entire velopharyngeal mechanism. [10][12] Comparison between multiview videofluoroscopy and nasoendoscopy of velopharyngeal movements."/> [13] This diagnosis method is useful in assessing velopharyngeal (VP) closure in healthy individuals vs individuals who experience velar backed articulation (BA); given that it was found that healthy individuals had VP closure occur before tongue movement, whereas individuals with BA had VP closure occur after tongue movement when articulating words.[14]

Magnetic resonance imaging

A relatively new approach in the diagnosis is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is noninvasive. MRI uses the property of nuclear magnetic resonance to image nuclei of atoms inside the body. MRI is non-radiographic and therefore can be repeated more often in short periods of time. In addition, different studies show that the MRI is better as an imaging tool than videofluoroscopy for visualizing the anatomy of the velopharynx. There are some limitations of the MRI however. Unlike videofluoroscopy and nasopharyngoscopy, MRI does not show the movement of the velopharyngeal structures during speech. In addition, artifacts can be shown on the images when the patient moves while imaging or if the patient has orthodontic appliances. MRI is limited in children who are claustrophobic. Finally, MRI is much more expensive than videofluoroscopy or nasopharyngoscopy. Because of these limits, MRI is currently not widely used for clinical diagnostic purposes. [15][16]

Treatment

Speech pathology

Speech therapy will not correct velopharyngeal insufficiency. The condition results from abnormal structure and requires physical management (surgery, or a prosthetic device if surgery cannot be done). Speech therapy is appropriate to correct the compensatory articulation productions that develop as a result of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Speech therapy is most successful after correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Speech pathologists who are associated with a cleft palate/craniofacial team are most qualified for this type of therapy.[17][18]

Operation techniques

In patients with cleft palate, the palate must be repaired through a palatoplasty for normal velopharyngeal function. Despite the palatoplasty, 20-30% of these patients will still have some degree of velopharyngeal insufficiency, which will require surgical (or prosthetic) management for correction. Therefore, a secondary operation is necessary.[19] There is not one single operative approach to surgical correction of VPI. The surgical approach typically depends on the size of the velopharyngeal opening, its location, and the cause. [20] With diagnostic tools the surgeon is able to decide which technique should be used based on the anatomical situation of the individual. The goal of every operation is to achieve the best possible result with the technique assigned to each individual case, without causing upper airway obstruction and sleep apnea.[20]Nowadays the procedure that is chosen the most from the palatoplasties is the pharyngeal flap or sphincter palatoplasty.[2]

Pharyngeal flap

When a pharyngeal flap is used, a flap of the posterior wall is attached to the posterior border of the soft palate. The flap consists of mucosa and the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. The muscle stays attached to the pharyngeal wall at the upper side (superior flap) or at the lower side (inferior flap).[19] The function of the muscle is to obstruct the pharyngeal port at the moment that the pharyngeal lateral walls move towards each other.[2][19] It is important that the width and the level of insertion of the flap are properly constructed, because if the flap is too wide, the patient can have problems with breathing through the nose, which can result in sleep apnea.[21] Alternatively, a postoperative situation can be created with the same symptoms as before surgery. Some complications are possible; for example, the flap's width can change because of contraction of the flap. This results in a situation with the same symptoms of hypernasality after a few weeks of surgery.[2] Also a fistula can occur in 2.4% of the cases.[2][22]

Sphincter palatoplasty

When the sphincter pharyngoplasty is used, both sides of the superior-based palatopharyngeal mucosa and muscle flaps are elevated.[23][24] Because the distal parts (posterior tonsillar pillars, which the palatopharyngeal muscles are attached to)[2] are sutured to the other side of the posterior wall, the pharyngeal port will become smaller. As a result, the tissue flaps cross each other, leading to a smaller port in the middle and a shorter distance between the palate and posterior pharyngeal wall.[19]

There are a few advantages with using this technique. First of all the procedure is relatively easy to execute. This makes the operation cheaper, also because of a reduced anesthesia time. Secondly the dynamic sphincter can be moved as result of a remaining neuromuscular innervation, which gives a better function of the velopharyngeal port. Finally there is a lower complication rate, although obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) is associated.[2][19][25]

Both techniques are used often, but there is no standard operation. Pharyngeal flap surgery is not better than sphincter palatoplasty.[19] It is more upon the surgeon's experience, knowledge and preference which operation will be done. Also the patient’s age,[26][27] and the size and nature of the velopharyngeal defect, contribute to which technique is used.[27][28]

Posterior wall augmentation

Another option for diminishing the velopharyngeal port is posterior wall augmentation. This technique is not often used.[2] Additionally this technique can only be used for small gaps.[29] When this operation is performed there are several advantages. It is possible to narrow down the velopharyngeal port without modifying the function of the velum or lateral walls.[29] Furthermore, the chance of obstructing the airway is lower, because the port can be closed more precisely. Many materials have been used for this closure: petroleum jelly, paraffin, cartilage, adjacent soft tissue, silastic, fat, Teflon and proplast.[2] But results in the long term are very unpredictable. There are problems with tissue incompatibility and migration of the implant.[2][29] Even migration to the brain is noticed.

Prosthesis

Prostheses are used for nonsurgical closure in a situation of velopharyngeal dysfunction.[2][30] There are two types of prosthesis: the speech bulb and the palatal lift prosthesis.[2] The speech bulb is an acrylic body that can be placed in the velopharyngeal port and can achieve obstruction. The palatal lift prosthesis is comparable with the speech bulb, but with a metal skeleton attached to the acrylic body.[30] This will also obstruct the velopharyngeal port.[30] It is a good option for patients that have enough tissue but a poor control of the coordination and timing of velopharyngeal movement.[2][30] It is also used in patients with contraindications for surgery. It has also been used as a reversible test to confirm whether a surgical intervention would help.[2]

Etymology

The word velopharyngeal uses combining forms of velo- + pharyng-, referring to the soft palate (velum palatinum) and the pharynx.

References

- Kummer AW. (2020). Speech/Resonance Disorders and Velopharyngeal Dysfunction. In Kummer, AW. Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Conditions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Management, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Peter D. Witt, D’Antonio. Velopharyngeal insufficiency and secondary palatal management. Clinics in plastic surgery. 1993. Oct;20(4):707-21.

- Kummer AW, Marshall J, and Wilson M. (2015). Non-cleft causes of velopharyngeal dysfunction: Implications for Treatment. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 79(3):286-95.

- Wermker K, Lünenbürger H, Joos U, Kleinheinz J, Jung S et al. Results of speech improvement following simultaneous push-back together with velopharyngeal flap surgery in cleft palate patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013 Sep 13. pii: S1010-5182(13)00219-9.

- Kummer AW. (2020). Speech and Resonance Assessment. In Kummer, AW. Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Conditions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Management, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- 4. Kummer AW. (2011). Perceptual assessment of resonance and velopharyngeal dysfunction. Seminars in Speech and Language, 32(2), 159-167.

- Kummer AW. (2020). Nasometry. In Kummer, AW. Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Conditions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Management, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Sweeney, T., & Sell, D. (2008). Relationship between perceptual ratings of nasality and nasometry in children/adolescents with cleft palate and/or velopharyngeal dysfunction. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 43(3), 265–282.

- Kummer AW. (2020). Nasopharyngoscopy. In Kummer, AW. Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Conditions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Management, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Lam DJ, Starr JR, Perkins JA, Lewis CW, Eblen LE, Dunlap J, Sie KC. A comparison of nasoendoscopy and multiview videofluoroscopy in assessing velopharyngeal insufficiency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Mar;134(3):394-402.

- Henningsson G, Isberg A. Comparison between multiview videofluoroscopy and nasoendoscopy of velopharyngeal movements. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1991 Oct;28(4):413-7

- Willging JP. Velopharyngeal insufficiency. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Dec;11(6):452-5.

- Havstam C, Lohmander A, Persson C, Dotevall H, Lith A, Lilja J. (2005). Evaluation of VPI-assessment with videofluoroscopy and nasoendoscopy. British Journal of Plastic Surgery, 58(7), 922-931.

- Tezuka, Masahiro; Ogata, Yuko; Matsunaga, Kazuhide; Mitsuyasu, Takeshi; Hasegawa, Sachiyo; Nakamura, Norifumi (2014-05-01). "Perceptual and videofluoroscopic analyses of relation between backed articulation and velopharyngeal closure following cleft palate repair". Oral Science International. 11 (2): 60–67. doi:10.1016/S1348-8643(14)00009-3. ISSN 1348-8643.

- S. Vadodaria, T. E. E. Goodacre and P. Anslow; Does MRI contribute to the investigation of palatal function?; Br J Plast Surg. 2000 Apr;53(3):191-9.

- Ruda, JM, Krakovitx, P, Rose AS. (2012). A Review of the Evaluation and Management of Velopharyngeal Insufficiency in Children. Otolaryngology Clinics, 45(3), 653-669.

- Kummer AW. (2011). Speech therapy for errors secondary to cleft palate and velopharyngeal dysfunction. Seminars in Speech and Language, 32(2), 191-199. Kummer AW. (2020).

- Kummer AW. (2020). Speech Therapy. In Kummer, AW. Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Conditions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinical Management, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Jessica Collins et al. Ontario, Canada. Pharyngeal flap versus sphincter pharyngoplasty for the treatment of velopharyngeal insufficiency: A meta-analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012 Jul;65(7):864-8.

- Ysunza A, Pamplona C, Ramírez E, Molina F, Mendoza M, Silva A. Velopharyngeal surgery: a prospective randomized study of pharyngeal flaps and sphincter pharyngoplasties, Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Nov;110(6):1401-7.

- Mc Williams BJ, Morris HL, Shelton RL: Cleft Palate speech. Philadelphia. BC Decker 1990, p 71

- Murthy AS, Parikh PM, Cristion C, et al. Fustila after 2-flap palatoplasty: a 20-year review. Ann Plast Surg. 2009. 63(6):632-5

- Dec W, Shetye PR, Grayson BH, et al. Incidence of oronasal fistula formation after nasoalveolar molding and primary cleft repair. J Craniofac Surg. 2013 . 24(1):57-61.

- Losken A, Williams JK, Burstein FD, et al. An outcome evaluation of sphincter pharyngoplasty for management of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003. 112(7):1755-61

- Witt PD, Marsh JL, Muntz HR, et al. Acute obstructive sleep apnea as a complication of sphincter pharyngoplasty. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1996. 33(3):183-9.

- Kirschner RE, Randall P, Wang P, et al. Cleft palate repair at 3 to 7 months of age. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105:2127e32.

- Peat BG, Albery EH, Jones K, Pigott RW. Tailoring velopharyngeal surgery: the influence of etiology and type of operation. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994;93:948e53.

- Shprintzen RJ, Lewin ML, Croft CB, et al. A comprehensive study of pharyngeal flap surgery: Tailor made flaps. Cleft Palate J 1979;16:46e55.

- Gray SD, Pinborough-zimmerman J, Catten M, et al. Posterior wall augmentation for treatment of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999. 121(1):107-12.

- Aboloyoun AI, Ghorab S, Farooq MU. Palatal lifting prosthesis and velopharyngeal insufficiency: preliminary report. Acta Med. Acad. 2013; 42(1):55-60