Pushtimarg

Pushtimarg (lit. 'the Path of Nourishing, Flourishing'), also known as Vallabha Sampradaya, is a subtradition of the Rudra Sampradaya - Vaishnavism. It was founded in the early 16th century by Vallabhacharya (1479–1531) and was later expanded by his descendants, particularly Vitthalanatha.[1][2] Pushtimarg adherents either worship Krishna alone in his prominent forms of Shrinathji, Madanamohana, Vitthala, and Dvarakadhisha, or with his consort and divine energy Radha, also called Swaminiji.[3][4][5] The tradition follows universal-love-themed devotional practices of youthful Krishna which are found in the Bhagavata Purana and those related to pastimes of Govardhana Hill.[1][6][7]

_and_the_Dancing_Gopis._Pichhavai_from_the_Temple_of_Nathdvara%252C_Rajasthan%252C_19_sent._Staatlische_Museen%252C_Berlin..jpg.webp)

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

The Pushtimarg subtradition subscribes to the Shuddhadvaita Vedantic teachings of Vallabhacharya, one that shares certain ideas with Advaita Vedanta, Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita Vedanta.[8] According to this philosophy, Krishna is considered to be the supreme being, the source of everything that exists and the human soul is imbued with Krishna's divine light and spiritual liberation results from Krishna's grace.[9] Ashtachap – eight Bhakti Movement poets, including the blind devotee-poet Surdas has major contribution in the growth of Pushtimarg.[9][10]

The followers of this tradition are called Pushtimargis[2] or Pushtimargiya Vaishnavas.[11] It has significant following in Indian states of Rajasthan and Gujarat, as well as its regional diaspora around the world.[1][12] The Shrinathji Temple in Nathdwara is the main shrine of Pushtimarg, which traces its origin back to 1669.[13][12]

Founder and History

Vallabhacharya was born into a Telugu Brahmin family in South India. His maternal grandfather was a priest in the royal court of the Vijayanagara Empire.[14] Vallabha's family fled Varanasi after they learnt about an imminent Islamic attack on the city, then spent the early years with baby Vallabha hiding in the forests of Chhattisgarh.[14]

As part of his education, Vallabha studied Vedic literature and other Hindu texts. He worked in the temples of the Vijayanagara court, and then embarked on a years-long pilgrimage to the major sacred sites of Hinduism on the Indian subcontinent.[14] He met scholars of Advaita Vedanta, Vishishtadvaita, Dvaita Vedanta, as well as his contemporary, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. His visit to Vrindavan in the north persuaded him to accept and dedicate himself to the bhakti of Krishna and writing his philosophical premises in Sanskrit and a few in the Braj language. His devotional mantra "Sri Krishna Sharanam Mam" (Shri Krishna is my refuge) became the initiatory mantra of Pushtimargis.[14] The term pushti to Vallabha implied "spiritual nourishment", a metaphor for Krishna's grace.[14][15]

Vallabhacharya has been a major scholar of the Bhakti tradition of Hinduism, as a devotional movement that emphasizes love and grace of God as an end in itself. Vallabhacharya initiated his first disciple Damodardas Harsani with a mantra along with the principles of Pushtimarga.[12]

When he died in 1531, Vallabacharya delivered the leadership of his movement to his elder son, Gopinatha. At Gopinatha's death in 1543, he was succeeded by his younger brother Vitthalanatha, a key figure in the development of the Pushtimarg. He codified the doctrine of the movement and died in 1586. At his death, the eight primary icons of Krishna of the Pushtimarg were distributed among his seven sons, plus one adopted son.[16] Some fragmentation followed, as each son of Vitthalanatha was able to confer initiations and start his own independent lineage, although the different branches remained unified by the doctrine. Among the descendants of Vitthalanatha, some acquired prestige as scholars, including Gokulanatha (1552-1641), Harirayaji Mahaprabhu (1591-1711), and Purusottamalalji (1668-1725). .[17]

In the 20th century, the Pushtimarg prospered thanks to the acquired affluence of some of its members, primarily Gujarati merchants. The Gujarati diaspora led to the foundation of important Pushtimarg centers in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.[18]

Key Tenets

Suddhadvaita

Vallabha formulated the philosophy of Śuddhādvaita in response to the Advaita Vedānta of Śaṅkara, which he called Maryādā Mārga or Path of Limitations. Vallabha rejected the concept of Māyā, stating that the world was a manifestation of the Supreme Absolute and could not be tainted, nor could it change.[19] According to Vallabha, Brahman consists of existence (sat), consciousness (chit), and bliss (ananda), and manifests completely as Kr̥ṣṇa himself.[7]

Seva

The purpose of this tradition is to perform sevā (selfless service) out of love for Kr̥ṣṇa. According to Vallabhacharya, through single minded religiosity, a devotee would achieve awareness that there is nothing in the word that is not Kr̥ṣṇa.[20]

Religious Praxis

Vallabha stated that religious disciplines that focused on Vedic sacrifices, temple rituals, puja, meditation, and yoga had limited value. The school rejects ascetic lifestyle and cherishes householder lifestyle, wherein the followers see themselves as participants and companions of Krishna, and their daily life as an ongoing raslila.[9]

Practices

Brahmsambandha and Initiation

The formal initition into the Pushtimarg is through the administration of the Brahmasambandha mantra. The absolute and exclusive rights to grant this mantra, in order to remove the doṣas (faults) of a jīva (soul) lie only with the direct male descendants of Vallabhācārya. According to Vallabha, he received the Brahmasambandha mantra from Kr̥ṣṇa one night in Gokula. The next morning Vallabha administered the mantra to Damodaradāsa Harasānī, who would become the first member of the sampradaya.[21][22]

In Vallabhācārya's time, an (adult) to-be devotee would ask Vallabha to admit him, and if Vallabha was willing to take the potential devotee, he would ask him to bathe and return. Vallabha would then administer the mantra, asking the devotee to use Kr̥ṣṇa's name and to devotee everything he had to Kr̥ṣṇa, after which Vallabha would begin the spiritual education on doctrines and texts.[21][22]

In modern times the majority of members of the sect are born into Pushtimarg families, with the administering of the mantra being split in two ceremonies. The first when the children are about five years old, is when the first part of the mantra: "śrī kr̥ṣṇaḥ śaraṇam mama" and a tulasī necklace is given. When the boys turn twelve or before girl's marriage, a day-long fast occurs. The devotee to be then is asked to devote his or her mind, body, wealth, wife, household, senses, and everything else to Kr̥ṣṇa, after which he or she is considered a proper member of the sampradaya. The mantra and initiation is always and make only be performed by the direct male descendants of Vallabha.[22][21]

Houses and Svarūpas in the Puṣtimārga

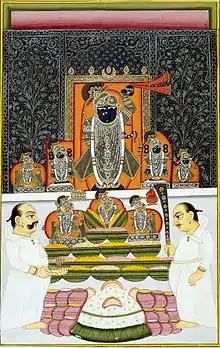

Viṭṭhalanātha had seven sons among whom he distributed nine major svarūpas of Kr̥ṣṇa that were worshipped by the Puṣṭimārga. Each son founded a lineage that served as leaders of the sampradays. Several forms/icons of Krishna are worshiped in the sect. Here are the sons of Viṭṭhalanātha, their svarūpas and where they currently reside.[23]

- Giridhara, whose descendants hold Śrī Nāthajī (Nāthadvāra, Rajasthan), Śrī Navanītapriyajī (Nāthadvāra, Rajasthan), and Śrī Mathureśajī, (Jatipurā, Uttar Pradesh)

- Govindarāya, whose desendants hold Śrī Viṭṭhalanāthajī (Nāthadvāra, Rajasthan)

- Bālakr̥ṣṇa, who descendants hold Śrī Dvārakānāthajī (Kāṁkarolī, Rajasthan)

- Gokulanātha, whose descendants hold Śrī Gokulanāthajī (Gokula, Uttar Pradesh)

- Raghunātha, whose desendants hold Śrī Gokulacandramājī (Kāmabana, Rajasthan)

- Yadunātha, whose descendants hold Śrī Balakr̥ṣṇajī (Sūrata, Gujarat) and Śrī Mukundarāyajī (Vārānasī, Uttar Pradesh)[note 1]

- Ghanaśyāma, whose descendants hold Śrī Madanamohanajī (Kāmabana, Rajasthan)

- Tulasīdāsa aka Lālajī, whose descendants hold Śrī Gopināthajī (Br̥ndābana, Uttar Pradesh, until 1947 at Ḍeragāzīkhān, Sindh)[note 2]

Pushtimarg Seva Prakar (devotional worship in Pushtimarg)

Seva is a key element of worship in Pushti Marg. All followers are expected to do seva to their personal icon of Krishna. In Pushti Marg, where the descendants of shrimad Vallabhcharyaji reside and perform Seva of their own idol of Shri krishna is called a "haveli" - literally a "mansion". Here the seva of thakurji(Shri Krishna) is performed with the bhaav of the Nandalaya. There is a daily routine of allowing the laity to have "darshan" (adore) the divine icon 8 times a day. The Vallabhkul adorn the icon in keeping with Pushti traditions and follow a colourful calendar of festivals.

Some of the important aspects of Pushtimarg Seva are:

- Raag (playing and hearing traditional Haveli music)

- Bhog (offering pure vegetarian saatvik food that does not contain any meat or such vegetables as onion, garlic, cabbage, carrots, and a few others)

- Vastra and Shringar (decorating the deity with beautiful clothes and adorning the deity with jewellery)

All of the above three are included in the daily seva (devotional service) which all followers of Pushtimarg offer to their Thakurji (personal Krishna deity), and all of them have been traditionally prescribed by Goswami Shri Vitthalnathji almost five hundred years ago. Shri Vitthalnathji is also called Gusainji (Vallabhacharya's second son). The raag, bhog, and vastra and shringar offerings vary daily according to the season, the date, and time of day, and this is the main reason why this path is so colourful and alive.

Seva is the most important way to attain Pushti in Pushtimarg and has been prescribed by Vallabhacharya as the fundamental tenet. All principles and tenets of Shuddhadvaita Vaishnavism stem out from here.

Pilgrimage

Baithak or Bethak, literally "seat", is the site considered sacred by the followers of the Pushtimarg for performing devotional rituals. These sites are spread across India and are chiefly concentrated in Braj region in Uttar Pradesh and in western state of Gujarat. Total 142 Baithaks are considered sacred; 84 of Vallabhacharya, 28 of his son Viththalanath Gusainji and 30 of his seven grandsons. They mark public events in their lives. Some of them are restricted or foreboding.[24]

Festivals

Pushti Marg followers celebrate several festivals. Icons are dressed and bejeweled to suit the season and the mood of the festival. All festivals are accompanied by a vegetarian feast which is offered to the deity and later distributed to the laity. Most festivals mark the important events in the life of Krishna, the birth of one of Vishnu's major avatars (Ram Navami, Nrushi Jayanti, Janmashtami (Krishna), Vaman Dwadashi), the festivals marking the change of seasons, the day of installation of an icon at the temple and the birthdays of sect's leaders and their descendants.

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Music

Haveli Sangeet or Kirtans are devotional hymns written by the asht sakhas for and about Shrinathji. The instruments played during Kirtan include zanz, manjira, dholak, pakhavaj/mrudang, daff, tampura, veena, harmonium, tabla, etc.

Works

Works by Vallabha

Vallabhacharya composed many Sanskrit philosophical and devotional books during his lifetime which includes:[25]

- Subhodinī, a partial commentary on the Bhāgavata Purāṇa

- Aṇubhāṣya, a partial commentary on the Brahmasūtra of Bādarāyaṇa

- Tattvārthadīpanibandha, a text interpreting existing Hindu scriptures through Vallabha's philosphy of Śuddhādvaita

- Tattvārthadīpanibandhaprakāśa, a commentary on the Tattvārthadīpanibandha

- Ṣoḍaśagrantha, sixteen treatises on important facets of Śuddhādvaita and theology of the Puṣṭimārga

Notes

- There is a succession dispute among the descendants of Yadunātha over the primacy of each svarūpa.

- Tulasīdāsa was an adopted son of Viṭṭhalanātha, and the svarūpa in his descendants' possession is of less significance than the other svarūpas.

References

- Vallabhacharya, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Matt Stefon and Wendy Doniger (2015)

- Kim, Hanna H. (2016), "In service of God and Geography: Tracing Five Centuries of the Vallabhacharya Sampradaya. Book review: Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and its Movement to the West, by E. Allen Richardson", Anthropology Faculty Publications 29, Adelphi University

- E. Allen Richardson (2014). Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West. McFarland. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-4766-1596-7.

- Bangha, Imre (2006). "Courtly and Religious communities as Centres of Literary Activity in Eighteenth-Century India" (PDF). Indologia Orient: 12.

- Vemsani, Lavanya (2016-06-13). Krishna in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Hindu Lord of Many Names: An Encyclopedia of the Hindu Lord of Many Names. ABC-CLIO. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-61069-211-3.

- E. Allen Richardson (2014). Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West. McFarland. pp. 12–21. ISBN 978-1-4766-1596-7.

- Edwin F. Bryant (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 477–484. ISBN 978-0-19-972431-4.

- E. Allen Richardson (2014). Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West. McFarland. pp. 20–23, 189–195. ISBN 978-1-4766-1596-7.

- Lochtefeld, James G (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. Rosen Publishing. pp. 539-540. ISBN 978-0823931804.

- Richard Keith Barz (1976). The Bhakti Sect of Vallabhācārya. Thomson Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-8-1215-05765.

- Harirāya (1972). 41 [i.e. Ikatālīsa] baṛe śikshāpatra: mūḷa śloka, ślokārtha, evaṃ vyākhyā sahita (in Hindi). Śrī Vaishṇava Mitra Maṇḍala. p. 297.

- Jindel, Rajendra (1976). Culture of a Sacred Town: A Sociological Study of Nathdwara. Popular Prakashan. pp. 21–22, 34, 37. ISBN 978-8-17154-0402.

- Wendy Doniger (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 781. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase. pp. 475–477. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- E. Allen Richardson (2014). Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West. McFarland. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4766-1596-7.

- Richard Keith Barz (1976). The Bhakti Sect of Vallabhācārya. Thomson Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-8-1215-05765.

- Richard Keith Barz (1976). The Bhakti Sect of Vallabhācāryaji. Thomson Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-8-1215-05765.

- E. Allen Richardson (2014). Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharyaji in India and Its Movement to the West. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1596-7.

- Saha, Shandip (2004). "Tracing the History of the Puṣṭi Mārga (1493-1670)". Creating a Community of Grace: A History of the Puṣṭi Mārga in Northern and Western India (1493-1905) (Thesis). University of Ottowa. p. 98-106.

- Saha 2004, p. 98-106.

- Barz 2018.

- Barz 1992, p. 17-20.

- Barz, Richard (1992) [First edition 1976]. The Bhakti Sect of Vallabhācārya (3rd ed.). Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 54–55.

- E. Allen Richardson (8 August 2014). Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West. McFarland. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-4766-1596-7. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- Barz, Richard (2018). "Vallabha". In Jacobsen, Knut A.; Basu, Helene; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online. Brill.

- Saha 2004, p. 118.

Further reading

- E. Allen Richardson. Seeing Krishna in America: The Hindu Bhakti Tradition of Vallabhacharya in India and Its Movement to the West. Jefferson: McFarland, 2014. 240 pp. ISBN 978-0-7864-5973-5.

- The Path of Grace: Social Organization and Temple Worship in a Vaishnava Sect. By Peter Bennett. Delhi: Hindustan Publishing Corporation, 1993. xi, 230 pp.