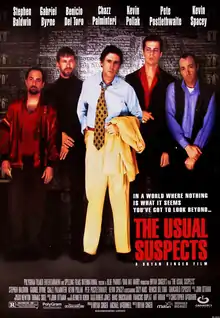

The Usual Suspects

The Usual Suspects is a 1995 mystery crime thriller film[5] directed by Bryan Singer and written by Christopher McQuarrie. It stars Stephen Baldwin, Gabriel Byrne, Benicio del Toro, Kevin Pollak, Chazz Palminteri, Pete Postlethwaite, and Kevin Spacey.

| The Usual Suspects | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bryan Singer |

| Written by | Christopher McQuarrie |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Newton Thomas Sigel |

| Edited by | John Ottman |

| Music by | John Ottman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes[1] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6 million[3] |

| Box office | $67 million[4] |

The plot follows the interrogation of Roger "Verbal" Kint, a small-time con man, who is one of only two survivors of a massacre and fire on a ship docked at the Port of Los Angeles. Through flashback and narration, Kint tells an interrogator a convoluted story of events that led him and his criminal companions to the boat, and of a mysterious crime lord—known as Keyser Söze—who controlled them. The film was shot on a $6 million budget and began as a title taken from a column in Spy magazine called The Usual Suspects, after one of Claude Rains' most memorable lines in the classic film Casablanca, and Singer thought that it would make a good title for a film.

The film was shown out of competition at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival[6] and then initially released in a few theaters. It received favorable reviews and was eventually given a wider release. The praise was towards the mystery elements, the screenplay, the plot twist and Spacey's performance. McQuarrie won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and Spacey won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance. The Writers Guild of America ranked the film as having the 35th greatest screenplay of all time.[7]

Plot

Career criminal Dean Keaton lies badly wounded on a ship docked in San Pedro Bay. He is confronted by a mysterious figure he calls "Keyser," who shoots him dead and sets fire to the ship. The next day, the police recover 27 bodies and only two survivors: Arkosh Kovash ("Ákos Kovács"), a Hungarian mobster hospitalized with severe burns, and Roger "Verbal" Kint, a physically disabled con artist. U.S. Customs agent Dave Kujan flies to Los Angeles from New York City to interrogate Verbal. The men are left alone in a borrowed office belonging to LAPD police sergeant Jeff Rabin while FBI agent Jack Baer visits a hospitalized Kovash. The events that led Keaton, Verbal, and their associates onto the ship are then described by Verbal via flashback.

Six weeks earlier in New York City, Keaton and Verbal are arrested alongside fellow criminals Michael McManus, Fred Fenster, and Todd Hockney and placed in a police lineup as suspects in a truck hijacking that none of them admits to participating in. Believing the police were unfairly harassing them, McManus proposes they pull a heist to get revenge on the NYPD. Trying to go straight, Keaton initially refuses but eventually agrees to help rob a jewel smuggler being escorted by corrupt cops, netting millions in emeralds and getting over fifty cops arrested after leaking their activities to the press. They then go to California to fence the jewels through a man named Redfoot, who connects them with another jewel heist, but it goes badly and the contents are instead revealed to be China White (synthetic heroin). The men learn that the job was arranged by a lawyer named Kobayashi, who says he arranged for their arrests in New York and that his employer, mysterious Turkish crime lord Keyser Söze, from whom each of the men has unwittingly stolen, has ordered them to raid a ship holding Argentinian drug dealers and destroy $91 million worth of cocaine being sold on board. The cash brought for the exchange will be their reward.

During Kujan's interrogation, he learns that there was no cocaine on the ship, and Söze was seen onboard. At the hospital, Baer learns that Kovács has seen Söze and has a sketch artist begin making a picture. Verbal then tells Kujan a legend about Söze: he was a small-time drug runner who murdered his own family when they were being held hostage by Hungarian mobsters, then massacred the mobsters and their families before disappearing, and from then on conducted business only indirectly through underlings who are mostly unfamiliar with their true employer. Söze thus became a fearsome urban legend, "a spook story that criminals tell their kids at night."

Concluding his story, Verbal reveals that Fenster was killed after trying to flee; the men then threatened Kobayashi, only to accept the assignment when he threatened their loved ones. The men attacked the ship during the night, killing several Argentinian and Hungarian gangsters before discovering that there was no cocaine. An unseen assailant killed Hockney, McManus, Keaton, and a prisoner in one of the ship's cabins. The mysterious figure then set fire to the ship as Verbal looked on from a hiding place on the dock.

Kujan deduces that Keaton must be Söze, as the prisoner killed on the ship was Arturo Marquez, a smuggler who escaped prosecution by claiming that he could identify Söze. Marquez was represented by lawyer Edie Finneran, Keaton's girlfriend, who was recently murdered. Kujan claims that the Argentinians took Marquez to sell him to Söze's Hungarian rivals. Keaton then used the assault so that he could kill Marquez personally and fake his own death. Verbal finally confesses that Keaton had been behind everything, but refuses to testify in court. Verbal's bail is posted, and he is released.

Moments later, Kujan realizes Verbal seemingly fabricated his entire story, improvising on the spot by piecing together details from random items in Rabin's cluttered office. Verbal walks outside, gradually losing his limp and flexing his supposedly disabled hand. As Kujan pursues Verbal, a fax arrives at the police station with the artist's facial composite of Söze. The picture resembles Verbal, revealing that he was Söze the entire time. Söze enters a car driven by "Kobayashi" and leaves, moments before Kujan arrives on the scene.

Cast

- Kevin Spacey as Roger "Verbal" Kint:

Singer and McQuarrie sent the screenplay for the film to Spacey without telling him which role was written for him. Spacey called Singer and told them that he was interested in the roles of Keaton and Kujan but was also intrigued by Kint who, as it turned out, was the role McQuarrie wrote with Spacey in mind.[8] - Gabriel Byrne as Dean Keaton:

Kevin Spacey met Byrne at a party and asked him to do the film. He read the screenplay and turned it down, thinking that the filmmakers could not pull it off. Byrne met screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie and Singer and was impressed by the latter's vision for the film. However, Byrne was also dealing with some personal problems at the time and backed out for 24 hours until the filmmakers agreed to shoot the film in Los Angeles, where Byrne lived, and make it in five weeks.[8] - Chazz Palminteri as Agent Dave Kujan:

Singer had always wanted Palminteri for the film, but he was always unavailable. The role was offered to Christopher Walken and Robert De Niro, both of whom turned it down. The filmmakers even had Al Pacino come in and read for the part, but he decided not to do it because he had just played a cop in Heat. Pacino would later say it was the one film he has regretted turning down the most. Palminteri became available, but only for a week. When he signed on, this persuaded the film's financial backers to support the film fully because he was a sufficiently high-profile star, thanks to the recent releases of A Bronx Tale and Bullets Over Broadway.[8] - Stephen Baldwin as Michael McManus:

Baldwin was tired of doing independent films where his expectations were not met; when he met with director Bryan Singer, he went into a 15-minute tirade telling him what it was like to work with him. After Baldwin was finished, Singer told him exactly what he expected and wanted, which impressed Baldwin.[8] - Benicio del Toro as Fred Fenster:

Spacey suggested del Toro for the role. The character was originally written with a Harry Dean Stanton-type actor in mind. Del Toro met with Singer and the film's casting director and told them that he did not want to audition because he did not feel comfortable doing them.[8] After reading the script, del Toro realized that his character's only purpose was to be killed to demonstrate Söze's power, and did not have any meaningful impact on the story. As a result, del Toro developed Fenster's unique, garbled speech pattern to make him more memorable as a character.[9] - Kevin Pollak as Todd Hockney:

He met with Singer about doing the film, but when he heard that two other actors were auditioning for the role, he came back, auditioned, and got the part.[8] - Pete Postlethwaite as Kobayashi

- Suzy Amis as Edie Finneran

- Giancarlo Esposito as FBI Agent Jack Baer

- Dan Hedaya as Sergeant Jeff Rabin

- Cástulo Guerra as Arturo Marquez

- Peter Greene as Redfoot (uncredited)

- Scott B. Morgan as Keyser Söze (in flashbacks) (uncredited)[10]

Production

Origins

Bryan Singer met Kevin Spacey at a party after a screening of the young filmmaker's first film, Public Access, at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Grand Jury Prize.[11] Spacey had been encouraged by a number of people he knew who had seen it,[8] and was so impressed that he told Singer and his screenwriting partner Christopher McQuarrie, that he wanted to be in whatever film they did next. Singer read a column in Spy magazine called "The Usual Suspects" after Claude Rains' line in Casablanca. Singer thought that it would be a good title for a film.[12] When asked by a reporter at Sundance what their next film was about, McQuarrie replied, "I guess it's about a bunch of criminals who meet in a police line-up,"[12] which incidentally was the first visual idea that he and Singer had for the poster: "five guys who meet in a line-up," Singer remembers.[13] The director also envisioned a tagline for the poster, "All of you can go to Hell."[8] Singer then asked the question, "What would possibly bring these five felons together in one line-up?"[14] McQuarrie revamped an idea from one of his own unpublished screenplays — the story of a man who murders his own family and disappears. The writer mixed this with the idea of a team of criminals.[12]

Söze's character is based on John List, a New Jersey accountant who murdered his family in 1971 and then disappeared for almost two decades, assuming a new identity before he was ultimately apprehended.[15] McQuarrie based the name of Keyser Söze on one of his previous supervisors, Kayser Sume, at a Los Angeles law firm where he worked,[16] but decided to change the last name because he thought that his former boss would object to how it was used. He found the word söze in his roommate's English-to-Turkish dictionary, which translates as "talk too much".[8] All the characters' names are taken from staff members of the law firm at the time of his employment.[8] McQuarrie had also worked for a detective agency, and this influenced the depiction of criminals and law enforcement officials in the script.[17]

Singer described the film as Double Indemnity meets Rashomon, and said that it was made "so you can go back and see all sorts of things you didn't realize were there the first time. You can get it a second time in a way you never could have the first time around."[18] He also compared the film's structure to Citizen Kane (which also contained an interrogator and a subject who is telling a story) and the criminal caper The Anderson Tapes.[14]

Pre-production

McQuarrie wrote nine drafts of his screenplay over five months, until Singer felt that it was ready to shop around to the studios. None were interested except for a European financing company.[19] McQuarrie and Singer had a difficult time getting the film made because of the non-linear story, the large amount of dialogue and the lack of cast attached to the project. Financiers wanted established stars, and offers for the small role of Redfoot (the L.A. fence who hooks up the five protagonists with Kobayashi) went out to Christopher Walken, Tommy Lee Jones, Jeff Bridges, Charlie Sheen, James Spader, Al Pacino, and Johnny Cash.[16] However, the European money allowed the film's producers to make offers to actors and assemble a cast. They were able to offer the actors only salaries that were well below their usual pay, but they agreed because of the quality of McQuarrie's script and the chance to work with one another.[13] That money fell through, and Singer used the script and the cast to attract PolyGram to pick up the film negative.[19]

About casting, Singer said, "You pick people not for what they are, but what you imagine they can turn into."[14] To research his role, Spacey met doctors and experts on cerebral palsy and talked with Singer about how it would fit dramatically in the film. They decided that it would affect only one side of his body.[8] According to Byrne, the cast bonded quickly during rehearsals.[11] Del Toro worked with Alan Shaterian to develop Fenster's distinctive, almost unintelligible speech patterns.[20] According to the actor, the source of his character's unusual speech patterns came from the realization that "the purpose of my character was to die."[8] Del Toro told Singer, "It really doesn't matter what I say, so I can go really far out with this and really make it uncomprehensible."[8]

Filming

The budget was set at $5.5 million, and the film was shot in 35 days[19] in Los Angeles, San Pedro and New York City.[18] Spacey said that they shot the interrogation scenes with Palminteri over a span of five to six days.[21] These scenes were also shot before the rest of the film.[8] The police lineup scene ran into scheduling conflicts because the actors kept blowing their lines. Screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie would feed the actors questions off-camera and they improvised their lines. When Stephen Baldwin gave his answer, he made the other actors break character.[8] Byrne remembers that they were often laughing between takes and "when they said, 'Action!', we'd barely be able to keep it together."[11] Spacey also said that the hardest part was not laughing through takes, with Baldwin and Pollak being the worst culprits.[21] Their goal was to get the usually serious Byrne to crack up.[21] They spent all morning trying unsuccessfully to film the scene. At lunch, a frustrated Singer angrily scolded the five actors, but, when they resumed, the cast continued to laugh through each take.[8] Byrne remembers, "Finally, Bryan just used one of the takes where we couldn't stay serious."[11] Singer and editor John Ottman used a combination of takes and kept the humor in to show the characters bonding with one another.[8]

While Del Toro told Singer how he was going to portray Fenster, he did not tell his cast members, and in their first scene together none of them understood what Del Toro was saying. Byrne confronted Singer and the director told him that for the lockup scene, "If you don't understand what he's saying maybe it's time we let the audience know that they don't need to know what he's saying."[8] This led to the inclusion of Kevin Pollak's improvised line, "What did you say?"

The stolen emeralds were real gemstones on loan for the film.[15]

Singer spent an 18-hour day shooting the underground parking garage robbery.[8] According to Byrne, by the next day Singer still did not have all of the footage that he wanted, and refused to stop filming in spite of the bonding company's threat to shut down the production.[8]

In the scene in which the crew meets Redfoot after the botched drug deal, Redfoot flicks his cigarette at McManus' face. The scene was originally to have Redfoot flick the cigarette at McManus's chest, but the actor missed and hit Baldwin's face by accident. Baldwin's reaction is genuine.[15]

Despite enclosed practical locations and a short shooting schedule, cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel "developed a way of shooting dialogue scenes with a combination of slow, creeping zooms and dolly moves that ended in tight close-ups," to add subtle energy to scenes.[22] "This style combined dolly movement with "imperceptible zooms" so that you'd always have a sense of motion in a limited space."[23]

In December 2017, amid several sexual misconduct allegations against Spacey, Byrne said that, at one point during shooting, production was shut down for two days because Spacey made unwanted sexual advances toward a younger actor.[24] Singer, who has himself been accused of sexual misconduct against minors,[25] has denied that Spacey behaved inappropriately on the set of the film.[26] However, Kevin Pollak, in a 2018 episode of his podcast Kevin Pollak's Chat Show, told another version of the story involving Spacey engaging in sexual acts with Singer's young French boyfriend with only several days left in the production, which disrupted filming and led to a bitter ruination of their relationship.[27]

Post-production

During the editing phase, Singer thought that they had completed the film two weeks early, but woke up one morning and realized that they needed that time to put together a sequence that convinced the audience that Dean Keaton was Söze — and then do the same for Verbal Kint because the film did not have "the punch that Chris had written so beautifully."[8] According to Ottman, he assembled the footage as a montage but it still did not work until he added an overlapping voice-over montage featuring key dialogue from several characters and had it relate to the images.[8] Early on, executives at Gramercy had problems pronouncing the name Keyser Söze and were worried that audiences would have the same problem. The studio decided to promote the character's name. Two weeks before the film debuted in theaters, "Who is Keyser Söze?" posters appeared at bus stops, and TV spots told people how to say the character's name.[28] In contrast with these efforts, all the actors in the film consistently mispronounce his name as "Soze", one syllable with a silent e, instead of "Söze".

Singer wanted the music for the boat heist to resemble Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1. The ending's music was based on a k.d. lang song.[29]

Release

Gramercy ran a pre-release promotion and advertising campaign before The Usual Suspects opened in the summer of 1995. Word of mouth marketing was used to advertise the film, and buses and billboards were plastered with the simple question, "Who is Keyser Söze?"[30]

The film was shown out of competition at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival and was well received by audiences and critics.[31] The film was then given an exclusive run in Los Angeles, where it took a combined $83,513, and New York City, where it made $132,294 on three screens in its opening weekend.[32] The film was then released in 42 theaters where it earned $645,363 on its opening weekend. It averaged a strong $4,181 per screen at 517 theaters and the following week added 300 locations.[19] It eventually made $23.3 million in the United States and Canada.[3] It grossed $43.6 million internationally for a worldwide total of $66.9 million.[4][33]

Reception

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has received a rating of 88%, based on 81 reviews, with an average rating of 7.80/10. The site's consensus reads, "Expertly shot and edited, The Usual Suspects gives the audience a simple plot and then piles on layers of deceit, twists, and violence before pulling out the rug from underneath."[34] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 77 out of 100, based on 22 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[35]

Roger Ebert, in a review for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave the film one and a half stars out of four, writing that it was confusing and uninteresting: "To the degree that I do understand, I don't care."[36] He also included the film in his "most hated films" list.[37] USA Today rated the film two and a half stars out of four, calling it "one of the most densely plotted mysteries in memory—though paradoxically, four-fifths of it is way too easy to predict."[38]

Rolling Stone praised Spacey, saying his "balls-out brilliant performance is Oscar bait all the way."[39] In his review for The Washington Post, Hal Hinson wrote, "Ultimately, The Usual Suspects may be too clever for its own good. The twist at the end is a corker, but crucial questions remain unanswered. What's interesting, though, is how little this intrudes on our enjoyment. After the movie you're still trying to connect the dots and make it all fit—and these days, how often can we say that?"[40]

In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin praised the performances of the cast: "Mr. Singer has assembled a fine ensemble cast of actors who can parry such lines, and whose performances mesh effortlessly despite their exaggerated differences in demeanor ... Without the violence or obvious bravado of Reservoir Dogs, these performers still create strong and fascinatingly ambiguous characters."[41] The Independent praised the film's ending: "The film's coup de grace is as elegant as it is unexpected. The whole movie plays back in your mind in perfect clarity—and turns out to be a completely different movie to the one you've been watching (rather better, in fact)."[42]

Accolades

At the 68th Academy Awards, Kevin Spacey won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor and Christopher McQuarrie won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. In his acceptance speech, Spacey said, "Well, whoever Keyser Söze is, I can tell you he's gonna get gloriously drunk tonight."[43]

| Association[44] | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20/20 Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won |

| Best Original Screenplay | Christopher McQuarrie | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | John Ottman | Nominated | |

| Academy Awards[45] | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won |

| Best Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen | Christopher McQuarrie | Won | |

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film | John Ottman | Nominated |

| Artios Awards[46] | Outstanding Achievement in Feature Film Casting – Drama | Francine Maisler | Won |

| Awards Circuit Community Awards | Best Motion Picture | Bryan Singer and Michael McDonnell | Nominated |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Kevin Spacey | Won | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Christopher McQuarrie | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | John Ottman | Nominated | |

| Best Cast Ensemble | Nominated | ||

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards[47] | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won |

| British Academy Film Awards[48] | Best Film | Bryan Singer and Michael McDonnell | Nominated |

| Best Original Screenplay | Christopher McQuarrie | Won | |

| Best Editing | John Ottman | Won | |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won |

| Best Screenplay | Christopher McQuarrie | Won | |

| Most Promising Actor | Benicio del Toro | Nominated | |

| Chlotrudis Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won |

| César Awards | Best Foreign Film | Nominated | |

| Critics' Choice Awards[49] | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won[lower-alpha 1] |

| Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won | |

| Best Screenplay | Christopher McQuarrie | Won | |

| Edgar Allan Poe Awards[50] | Best Motion Picture | Won | |

| Empire Awards[51] | Best Debut | Bryan Singer | Won |

| Golden Globe Awards[52] | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | Kevin Spacey | Nominated |

| Independent Spirit Awards[53] | Best Supporting Male | Benicio del Toro | Won |

| Best Screenplay | Christopher McQuarrie | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Newton Thomas Sigel | Nominated | |

| Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film | Bryan Singer | Won |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards[54] | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Runner-up |

| National Board of Review Awards[55] | Top 10 Films | 10th Place | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won | |

| Best Cast | Won | ||

| National Society of Film Critics Awards[56] | Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Runner-up |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards[57] | Best Supporting Actor | Won | |

| Online Film & Television Association Awards | Best Motion Picture | Won | |

| Sant Jordi Awards | Best Foreign Actor | Chazz Palminteri | Won |

| Sarajevo Film Festival | Audience Award for Best Feature Film | Bryan Singer | Won |

| Saturn Awards | Best Action/Adventure Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Bryan Singer | Nominated | |

| Best Music | John Ottman | Won | |

| Screen Actors Guild Awards[58] | Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role | Kevin Spacey | Nominated |

| Seattle International Film Festival | Best Director | Bryan Singer | Won |

| Best Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won | |

| Society of Texas Film Critics Awards | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Bryan Singer | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Kevin Spacey | Won | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Christopher McQuarrie | Won | |

| Southeastern Film Critics Association Awards | Best Picture | 8th Place | |

| Tokyo International Film Festival | Silver Award | Bryan Singer | Won |

| Turkish Film Critics Association Awards | Best Foreign Film | 2nd Place | |

Legacy

On June 17, 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "AFI's 10 Top 10"—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. The Usual Suspects was acknowledged as the tenth-best mystery film.[59] Verbal Kint was voted the #48 villain in "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains" in June 2003.

Entertainment Weekly cited the film as one of the "13 must-see heist movies".[60] Empire ranked Keyser Söze #69 in their "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters" poll.[61] In August 2016, James Charisma of Paste ranked The Usual Suspects among Kevin Spacey's greatest film performances.[62]

In 2013, the Writers Guild of America ranked the screenplay #35 on its list of 101 Greatest Screenplays ever written.[7]

Remake

In India, a critically panned Hindi-language adaptation of The Usual Suspects, titled Chocolate, was released in 2005.[63]

See also

References

- "The Usual Suspects (18)". British Board of Film Classification. May 26, 1995. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- "The Usual Suspects (1995)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- "The Usual Suspects". The Numbers. Archived from the original on April 6, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- "Selected Sundance alumni domestic vs international". Screen International. February 17, 1997. p. 18.

- "The Usual Suspects". Rotten Tomatoes.

- "Festival de Cannes: The Usual Suspects". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America, West. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Burnett, Robert Meyer (2002). "Round Up: Deposing The Usual Suspects". The Usual Suspects Special Edition DVD. MGM.

- Planas, Roque (January 30, 2015). "Benicio Del Toro's Weird Accent In 'The Usual Suspects' Should Have Won The Oscar For Best Foreign Film". Huffington Post.

- Mottram, James (2006). The Sundance Kids: How the Mavericks Took Back Hollywood (1st American paperback ed.). NY: Faber and Faber, Inc. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0865479674.

- Ryan, James (August 17, 1995). "The Usual Suspects Puts Together Unusual Cast". BPI Entertainment News Wire.

- Larsen, Ernest (2005). "The Usual Suspects". British Film Institute.

- Hartl, John (August 13, 1995). ""Surprises and No Holes" in Director's Prize-Winning Mystery". Seattle Times.

- Lacey, Liam (September 21, 1995). "Bryan Singer's Film Fever". The Globe and Mail.

- The Usual Suspects DVD commentary featuring Bryan Singer and Christopher McQuarrie, [2000]. Retrieved September 27, 2002

- Nashawaty, Chris (February 3, 2006). "Starring Lineup". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- Francis, Patrick (December 1, 1998). "Bryan Singer, Confidence Man". Moviemaker. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- Wells, Jeffrey (August 31, 1995). "Young Duo Makes Big Splash". The Times Union.

- "Suspects Found It Tough to Round Up Financing". The Hollywood Reporter. September 13, 1995.

- Hernandez, Barbara E (September 5, 1995). "What's in a name? Benicio Del Toro knows". Boston Globe.

- Parks, Louis B (August 19, 1995). "Everyone's Suspect". Houston Chronicle.

- Williams, David (July 2000). "Unusual Suspects". American Cinematographer. American Society of Cinematographers. 81 (7). Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- Gray, Simon (July 2006). "Hero Shots". American Cinematographer. American Society of Cinematographers. 87 (7). Archived from the original on September 4, 2009.

- Ramos, Dino-Ray (December 4, 2017). "Gabriel Byrne Says Kevin Spacey's "Inappropriate Sexual Behavior" Halted Production On 'The Usual Suspects'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- French, Alex; Potter, Maximillian (March 2019). "No One Is Going to Believe You". The Atlantic. Boston, Massachusetts: Emerson Collective. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Coggan, Devan (December 8, 2017). "Bryan Singer denies that Kevin Spacey's sexual misconduct held up The Usual Suspects". Entertainment Weekly. New York City: Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "BKPCS: AKA (Ask Kevin Anything) #358". YouTube. YouTube. June 12, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- Gordinier, Jeff (September 29, 1995). "Keyser on a Roll". Entertainment Weekly.

- Koppl, Rudy. "VALKYRIE – The Destruction of Madness". MusicfromtheMovies.com. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- Fried, John (June 1996). "The Usual Suspects". Cineaste. New York City: Cineaste Publishers, Inc. 22 (2). ISSN 0009-7004.

- "Auteurs bloat or float bulk of Cannes fest crop". Variety. June 9, 1995.

- Evans, Greg (April 22, 1995). "Suspects heists exclu B.O.; Brothers in pursuit". Variety.

- Klady, Leonard (February 19, 1996). "B.O. with a vengeance: $9.1 billion worldwide". Variety. p. 1.

- "The Usual Suspects". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- "The Usual Suspects". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- Ebert, Roger (August 18, 1995). "The Usual Suspects". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020 – via rogerebert.com.

- Ebert, Roger (August 11, 2005). "Ebert's Most Hated". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020 – via rogerebert.com.

- Clark, Mike (August 18, 1995). "Usual Suspects, usual thriller". USA Today.

- Travers, Peter (1995). "The Usual Suspects". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- Hinson, Hal (August 18, 1995). "Usual Suspects, Unusual Suspense". The Washington Post.

- Maslin, Janet (August 16, 1995). "Putting Guys Like That in a Room Together". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- Curtis, Quentin (August 27, 1995). "The thrill of The Usual Suspects is that it re-mythologises the crime movie". The Independent.

- Grimes, William (March 26, 1996). "Gibson Best Director for Braveheart, Best Film". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "The Usual Suspects: Awards". IMDb. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- "The 68th Academy Awards (1996) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. AMPAS. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Carr, Jay (December 18, 1995). "Hub critics pick Sense and Sensibility". Boston Globe.

- Boehm, Erich (April 29 – May 5, 1996). "Costume dramas win bulk of BAFTA awards". Variety.

- "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 1995". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008.

- "Category List – Best Motion Picture". Edgar Awards. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- "Empire Awards Past Winners – 1996". Empireonline.com. Bauer Consumer Media. 2003. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- Dutka, Elaine; Puig, Claudia (January 22, 1996). "'Sense,' 'Babe' Take Home Top Golden Globes". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- "'Leaving Las Vegas' Arrives in Big Way at Spirit Awards". Los Angeles Times. March 25, 1996. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- King, Susan (December 17, 1995). "'Las Vegas' Glitters for L.A. Film Critics". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- Evans, Greg (December 18, 1995 – December 31, 1996). "Crix picks praise Sense, Vegas". Variety.

- Holden, Stephen (January 4, 1996). "Babe' Is Chosen as Best Film By National Society of Critics". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- Maslin, Janet (December 15, 1995). "Leaving Las Vegas' Is Voted Best Film by Critics Circle". The New York Times. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- Collins, Scott (February 26, 1996). "Cage, Sarandon Capture Top Screen Actor Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10". American Film Institute. June 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- Ramisetti, Kirthana (March 6, 2008). "Pros and Cons". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters". Empire. London, England: Bauer Media Group. June 29, 2015. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- Charisma, James (August 15, 2016). "All 45 of Kevin Spacey's Movie Performances, Ranked". Paste. Avondale Estates, Georgia: Wolfgang's Vault. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- Pandohar, Jaspreet (September 11, 2005). "BBC - Movies - review - Chocolate (Deep Dark Secrets)". BBC Online. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Tied with Ed Harris for Apollo 13, Just Cause and Nixon.