Ligovo

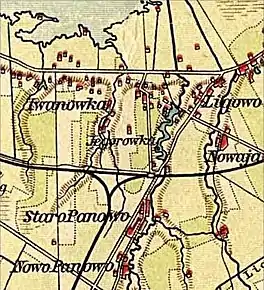

Ligovo (Russian: Лигово) is a historical area of the federal city of Saint Petersburg (Russia). It is located in the southern part of the city on the road leading to Petergof.

A settlement of east Slavs existed on the site of modern Ligovo from the 8th-9th centuries. Since then, Ligovo has been a court manor, an exemplary farm, a town, and a battleground during World War II. Currently, it is a suburb of Saint Petersburg, mostly composed of 1960s buildings. It is part of Uritsk Municipal Okrug, Krasnoselsky District.

History

Liiha is the name of the Izhorian village which was mentioned for the first time in the records named Vodskaya pyatina in 1500.

The name is derived from a small river previously called Liiha (from Finnish: Liiha: dirt, slush). Nowadays, this is called the Dudergofka river. The settlement is shown on Swedish maps of 15th century as "Liihala" or "Liihankulla" (i.e. Liihankylä) (kylä means village in Finnish).[1]

For over 1,000 years, the East Slavs have lived peacefully along the Neva River and in areas on the southern coast of Gulf of Finland alongside the less numerous Baltic Finns. From the 12th century, these territories were part of the large feudal state of the North-west of Russia — Lord of Great Novgorod (Russian: Господин Великий Новгород). By the 15th century, Novgorod territory became part of the Russian centralised state.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the expanding Swedish Empire spread to the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland. However, following the Great Northern War, Russian victory in 1721 ensured the return of these territories to the Russian crown.[2]

Ligovo mill on a postcard from the 1900s. 59°49′24″N 30°11′03″E |

Garden grotto (architect - M. A. Makarov) in the 1900s. 59°50′04″N 30°11′15″E. From construction there was only a hill |

Grande and Manor of count Orlov, Buxhoeveden, Kushelev

In 1703, Peter I made Saint Petersburg his capital and Ligovo became a suburb. During the 1710s, the emperor became involved in the development of the area: first, in 1712, he created an imperial farm in order to provide the imperial household with food - this included a dairy farm and kitchen gardens. Then in 1715, he dammed the river, creating a pond and mill which survived until war damage in 1941.[2]

Simultaneously, the Ligovsky channel was dug which drained water from the Dudergofka and the artificial lake, and so provided water for Ligovo.[2]

Many prominent people visited Logovo during this period:

- Anna Ivanovna on January, 20th, 1737 «a coffee saw on grange».

- Elizabeth Petrovna who wanted «to have dinner in tents».[1]

By the middle of 18th century, the farm was extended to include an orchard. The mill dam was near to the Peterhofskoye shosse and the small river has spread, having formed a pond stretched to a modern line of the railway (approximately 1,7 kilometres).[1]

In 1765, Russian empress Catherine II also built Gatchina Grange and House Kurakinikh, and presented the village to the Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov (along with Kipen, Shchungurovo, Ropsha); she often visited him here.

After Grigory Orlov's death in 1783, Ligovo was inherited by his pupil, Natalya Alexeyeva. She was the wife of Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden, Orlov's aide-de-camp. The manor was called Buxhoeveden during this period.[1]

In the 1840s, the manor of Buxhoeveden passed to Count G. G. Kushelev (junior). Kushelev continued the useful agricultural activity of Count Orlov, and Ligovo became an exemplary agricultural manor.

After Kushelev's death, the manor gradually fell into decay. This process of decay was exacerbated by the reforms of 1861.

In 1877 in buildings near a mill there was an attempt to set up a sanatorium.

In 1879, most of the manor passed to Kurikov's merchant.

The rural-industrial stage of the history of the settlement has begun, and the Baltic railway was soon extended to Ligovo.[1]

Suburb of Petersburg

The settlement became one of the rural suburbs of the capital. Local residents sold to summer residents dairy products, berries, fruit, greens. Ligovo abounded with a wide variety of summer residences — from own, expensive, enough intricate to the usual cheap country houses which are handed over by owners for summer.

For the account of affinity of Ligovo to Saint Petersburg and convenience of the message with it became more active building of constant summer residences.

As soon as the Saint Petersburg streets will be cleared of snow ..., from different directions Saint Petersburg — in spite of neither on a cold, nor on absence of the correct summer message with summer residences — chains of carts with furniture and different House stuff will be pulled in a direction for a city.[1]

Ligovo grew has built up with country quarters territory from the Baltic railway to the Peterhofskoye shosse.

Electric illumination and the water drain have been spent. Summer residences were under construction were various styles — there were towers turrets, verandahs, colour glasses. Process engineer K. M. Polezhaev and his son, the valid councillor of state B. K. Polezhayev became new heroes of Ligovo. Till now the park, and a pond local hit fur-trees name Polezhaevses.[1]

In the beginning of the 20th century in area was the Lutheranism centre — to ligovsky arrival colonies of Buksgevden and Panovo concerned.[3] Ligovo gradually developed and by 1917 was a satellite town.

After the October Revolution, in 1918 the city was renamed Uritsk in honour of the revolutionary and politician, Moisei Uritsky.

In 1925, town status was officially granted to it.

The decree of the Presidium of the Supreme body of RSFSR from November 27, 1938 formed the working settlement Ligovo.

Ligovo after 1945

In 1941-1945 of the Soviet Union and Germany participated in Second World War.

Ligovo has entered into territory on which took place fights for Leningrad (Siege of Leningrad operation).

Since December 1941 till January, 1944 on settlement territory there passed a front line. The essential part of the population has been taken out by German armies to a concentration camp «Dulag 154»,[4] the part of inhabitants has been evacuated by the Soviet armies to Leningrad.

All buildings and constructions have been destroyed. At deviation the German armies have put out of commission bridges, automobile and railways road. Besides, the set of objects has been mined. So, for example from station Dachnoye to station Ligovo sappers have taken and have neutralised minefields in density of 1500 pieces on road kilometre.[5]

After the war, the city territory became completely built up. On January 16, 1963, Uritsk became part of the city of Leningrad. It was included into Kirovsky District. In April 1973, it was transferred to Krasnoselsky District. In the 1960s-1970s, all the territory of Ligovo has been anew planned and built up by modern many-storeyed houses. Now the territory of Ligovo is a part of Uritsk Municipal Okrug

Notable natives

Mathilde Kschessinska was the only Polish prima ballerina assoluta in the world. She was born in Ligovo on 31 August [O.S. 19 August] 1872. The famous Russian ballerina of the late 19th and the early 20th century Anna Pavlova was born in Ligovo.

Monuments

Obelisk in memory of defenders of a city near to Ligovsky overpass.

References

- N. A., Perevezentseva (2004). По Балтийской железной дороге от Петербурга до Гатчины [On the Baltic railway from Petersburg to Gatchina] (in Russian). Russian: Перевезенцева Н. А. Ostrov Russian: Остров. ISBN 5-94500-007-8. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- Russian: Аминов Д., D. Aminov (1990). "Лигово - Урицк" [Ligovo-Uritsk]. Dialog Russian: Диалог (in Russian). Leningrad obkom CPSU Russian: Ленинградский обком КПСС. Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- "Российские немцы" [Russian Germans]. books of reference Russian: энциклопедии (in Russian). www.rdinfo.ru. p. 1. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- "Дулаг-154" [Dulag 154]. Hall of fighting glory (Russian: Зал боевой славы) (in Russian). Vysokokljuchevaja school (Russian: Высокоключевая школа). Archived from the original on 2009-08-17. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- Konarev, N. S. Russian: Н. С. Конарев. Железнодорожники в Великой Отечественной войне 1941–1945 [Railwaymen in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2009-06-30.