Upper Appomattox canal system

The Upper Appomattox Canal Navigation system allowed farmers who took their wheat and corn to mills on the Appomattox River, as far way as Farmville, Virginia, to ship the flour all the way to Petersburg from 1745 to 1891. The system included a navigation, modifications on the Appomattox River, a Canal around the falls Petersburg, and a turning basin in Petersburg to turn their narrow long boats around, unload the farm products from upstream and load up with manufactured goods from Petersburg. In Petersburg, workers could put goods on ships bound for the Chesapeake Bay and load goods from far away for Farmville and plantations upstream. Canal boats would return up river with manufactured goods. People who could afford it, rode in boats on the canal as the fastest and most comfortable ride. The river was used for transportation and shipping goods for over 100 years.

| Upper Appomattox Canal Navigation System | |

|---|---|

The Abutment Dam, the Appomattox Canal Dam, brought water to the Upper Appomattox Canal. | |

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat beam | 5 ft 0 in (1.52 m) |

| Locks | 17 Locks (Staircase fashion around the Fall Line and along the river) |

| Status | No longer in use since 1890 |

| Navigation authority | Virginia General Assembly |

| History | |

| Original owner | Upper Appomattox Canal company |

| Principal engineer | John Couty (1830) |

| Date of act | 1796 |

| Construction began | 1809 |

| Date completed | 1816 |

| Date closed | 1890 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Farmville, Virginia |

| End point | Petersburg, Virginia |

| Branch(es) | Appomattox River |

| Branch of | James River |

History

The River was modified for transportation around 1745 and further modified over its years of use. Much of the canal system was built by slaves. Freed Blacks of Israel Hill worked as Boatman.[1] The Canal took damage in the Civil War and was used until faster rail transportation was available.

Cleared 1745

The Appomattox River was cleared for bateau by 1745.[2] These boats were the same dimensions as the James River bateau, sixty feet long, six feet wide and two feet deep. It was also designed to carry the largest load through the smallest parts of the river system. Unlike the James River bateau, the Appomattox trips went up and down river so they were not designed to be sold as lumber at the end of the voyage.[3]

The Virginia General Assembly passed laws to protect navigation on the James River and Appomattox. By statute, a dam could not be built unless it had locks for boat passage.[4]

Upper Appomattox Company 1795

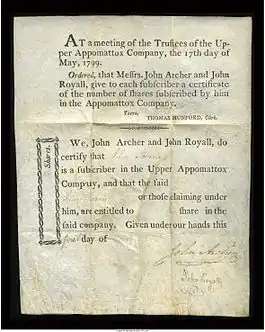

Stock Certificate on Vellum. | |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1795 |

| Defunct | 1890 |

Area served | Farmville, Virginia to Petersburg, Virginia and Chesterfield, Amelia, Buckingham and Cumberland between. |

Key people | In 1799

|

The Virginia General Assembly incorporated the Upper Appomattox Company in 1795. The state had bought 125 shares by 1801 to support the growth of transportation. In 1807, the company is allowed to sell bonds for one fourth of the expense of building the canal. A 335 foot long dam in the Appomattox diverted water to the canal. The canal was built entirely by enslaved Africans owned by the company.[4]

Canal built in 1816

The Appomattox Canal, built in 1816, connected 5.5 miles from the head of the falls at the Fall Line on the Appomattox River to the Turning basin in Petersburg, Virginia. Built for $60,000, the canal was big enough to carry the bateau, six feet wide and three feet deep. With another $10,000 it could carry all river traffic.[5] Slaves enhanced the Appomattox River from Farmville over 100 miles to Petersburg with numerous wing dams to keep the flow high.[3] The river also had four stone staircase locks. Four watermills along the river had locks in their dams. Two of these watermills had stone locks.[2]

The Canal around the falls had a navigable aqueduct made with Stone Arches and stone culverts to take boats over the Rohoic Creek confluence on the way to the canal basin.[2] A short distance from the Basin, connected a by carriage route, were deep water ports that allowed for transport of to goods to and from the Chesapeake Bay and beyond.[3]

Israel on the Appomattox

One third of Bateau were owned by Free people of color. Bateau owned by White People employed white boatmen as well as freemen and slaves. One fourth of all cargo was transported from Farmville in bateau on the Appomattox River.[4] Slaves on one plantation, including Sam White, inherited land from a repentant southerner, Richard Randolph, in 1810. He had freed them upon his death in 1796. They formed a town on the land and farmed, built buildings on the land and operated many of the boats on the Appomattox, transporting goods for a fee. They were still living there as freemen up to the time of the Emancipation Proclamation.[6]

Rebuilt in 1830

In 1829 the Virginia General Assembly hired a public engineer to determine the possibility and cost of connecting the upper Appomattox River to the Roanoke River at the Mouth of the Staunton from the Appomattox past Farmville by canal or rail.[7] However, that canal connection was never built.

The Upper Appomattox Canal, in Petersburg, was rebuilt by John Couty as a lock and dam system with a total of 17 locks and 8 miles. It was still designed for bateau.[2] Tolls were paid by shippers to support the cost of maintaining the locks and dams.[3] In fiscal year, 1831, boatmen shipped around 20,000 barrels of flour and 20,000 barrels of wheat; 5,000 hogsheads of tobacco leaf, and some tobacco stems; half a million pounds of manufactured goods, barrel staves, cotton, corn, salt, lime and iron.[4] By 1836, Petersburg was connected to docks at City Point by the City Point Railroad rather than carriage. Petersburg was also connected to the north by rail on the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad and the South on the Petersburg Railroad in the 1830s.

Eppington

Epps Falls, at the Eppington Plantation, were deemed dangerous for passing boats by the Virginia General Assembly. The General Assembly gave Archibald Thweatt, owner of Eppington, compensation from any damages but allowed the Upper Appomattox Canal company to build a dam and locks around the falls in 1819. Archibald Thweatt and his heirs were also given leave to build a grist mill on the dam.[8]

In the 1830s Eppington plantation at Epps Falls on the Appomattox River had 100 slaves, a warehouse and a dock. Neighboring farmers could ship farm produce from the docks.[9] There were large loading facilities. When coal was first mined at the Clover Hill Pits, in 1837, it was taken by mule, later by rail, to the docks at Epps Falls. A boat that could carry seven tons of coal, made a four-day round trip to Petersburg for two dollars and thirty eight cents. This would soon be replaced by transport on the Clover Hill Railroad.[10]

Water power below the basin in 1850

Water flowing below the Basin down into the Appomattox powered mills and factories.[3] The mills produced cotton, wool, hemp flax and flour. The flour was exported as far way as Brazil.[5]

Civil War damage 1865

During the Siege of Petersburg, in the American Civil War, there were not enough soldiers to block Union advancement in all places. The Confederate States Army dammed Rohoic Creek with a large dam that would be difficult to cross. The dam failed and washed away the 1826 navigable aqueduct and the Southside Railroad.

Upper Appomattox Canal company in Reconstruction 1872-1877

In 1872, W.E. Hinton, Jr, as president of the Upper Appomattox Canal Company, asked shareholders to agree to correct mismanagement, since there had not been a shareholder meeting since 1866. This mismanagement included paying out dividends before making repairs to the canal. Dividends were paid out ignoring 70 shares of stock, out of roughly 1100, which allowed others to get a higher dividend. Also, one shareholder who tore down canal property tried to sell off the bricks. An unauthorized grist mill was built using the canal water. One officer who let the city of Petersburg take cobbles from canal property to build a road across the canal property to the officers own mill. This made other rentals of water useless, since a road lay where their mills would be. The mill owner would have had to buy water rights to the water power in a competitive bid, but having built a road where their competition would build mills, they paid a much lower price for the water. Hinton suggested that $600 was a reasonable rent to charge the mill owner, because there should have been a competitive bid allowed.[11]

Senator Hinton, was elected as an officer in 1872 and got the right to sell bonds. In 1876, Bonds are given to Hinton as $4000 salary; sold to Captain N. M. Osborne and Major John Robinson of Baltimore and given to the State of Virginia, the Bank of Petersburg, and private banker N.M. Osborne and E.S. Stith as collateral. The money from the bonds, was used to rebuild the Navigable Aqueduct on Old Town Creek, now called Rohoic Creek, and rebuild a lock keeper's home, buildings, several locks and dams for mills.[12][13] The next year the General Assembly gave the company the right to sell bonds to buy company stock back from the state. The General Assembly also let the company have an additional 10 years to buy back the stock.[14]

After Reconstruction 1877

After the Emancipation Proclamation and after the end of Reconstruction Era on April 2, 1877,the Virginia General Assembly approved the Virginia governor providing twenty to twenty five prisoners under convict lease to the Upper Appomattox canal company.[15] Convict Lease was described by the writer Douglas A. Blackmon as "a system in which armies of free men, guilty of no crimes and entitled by law to freedom, were compelled to labor without compensation, were repeatedly bought and sold, and were forced to do the bidding of white masters through ... physical coercion."[16]

Farmville and Powhatan Railroad connects to James River 1891

The Canal was used in part until the 1890s.[5] In 1890, the Canal would have had competition with the Farmville and Powhatan Railroad which competed with the Southside Railroad. The Farmville and Powhatan was connected all the way to Bermuda Hundred on the James River and Chester, Virginia, just north of Petersburg, in 1891. The railroad was narrow gauge but could provide transportation for goods and people over a similar route as the canal in just four hours. The railroads were pricing lower due to competition and made the trip in hours rather than days.[17]

What remains of the canal today

The wing dams can still be seen in some places.[2] The first few miles of the canal from the abutment dam, a contour canal, can be walked in Appomattox River Park in Petersburg. Remains of the navigable aqueduct and other stone work remain on the Appomattox River & Heritage Trail in Petersburg, Virginia. The straight part of the canal to the turning basin follows Upper Appomattox Street and was part of the Seaboard Air Line Railroad for many years. The location of the turning basin is at Dunlop Street, High Street, South Street and Commerce. The water used to flow down Canal street back to the Appomattox River.[18] Eppington is still in Chesterfield and is open to the public a few days a year.[19] Israel Hill has a historical marker in Farmville, Virginia.[1]

References

- Jones, Randy (2009-04-15). "Ten New State Historical Highway Markers Approved" (PDF). Department of Historic Resources. Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

- Trout III, W (1973-06-13). "The Upper Appomattox Navigation, Virginia" (PDF). American Canals. American Canal Society. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- Melvin Patrick Ely (1 December 2010). Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s Through the Civil War. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-0-307-77342-5.

- Annual Report of the Board of Public Works to the General Assembly of Virginia: With the Accompanying Documents. Thomas Ritchie. 1830. pp. 145–156.

- Diane Barnes (1 June 2008). Artisan Workers in the Upper South: Petersburg, Virginia, 1820-1865. LSU Press. pp. 22–26. ISBN 978-0-8071-3419-1.

- Ely, Melvin (August 5, 2007). "'Israel on the Appomattox'". New York Times. New York, New York. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- Virginia. Board of Public Works (1829). Annual Report of the Board of Public Works to the General Assembly of Virginia, with the Accompanying Documents. pp. 589–590.

- Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia. 1819. pp. 195–196.

- Stith, M.D. (August 23, 1989). "Eppington: Crown Jewel of Chesterfield County" (PDF). Eppington Foundation. Eppington Foundation. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- Gerald P. Wilkes (1988). MINING HISTORY OF THE RICHMOND COALFIELD OF VIRGINIA (PDF) (Report). VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 85. p. 10,29–30. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- Hinton, William (1872-11-11). "To the stockholders of the Upper Appomattox Company". Duke University Libraries. Duke University Libraries. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- Journal of the Senate of Virginia. Commonwealth of Virginia. 1878. pp. 35–52.

- Journal. 1878. pp. 32–45.

- Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia. 1877. pp. 218–219.

- Virginia (1877). Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia. p. 304.

- Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, (2008) ISBN 978-0-385-50625-0, p. 4

- Virginia. Railroad Commissioner (1893). Annual Report of the Railroad Commissioner of the State of Virginia. R.F. Walker, Superintendent Pub. Print. pp. xx–xxx.

- Jost, Scott (March 12, 2010). "More Images from the Indian Town Creek Aqueduct Site". Chesapeake Bay Watershed Confluences. Bridgewater College. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- "Eppington Plantation". Eppington Foundation. Eppington Foundation. 2014. Retrieved 2017-01-29.